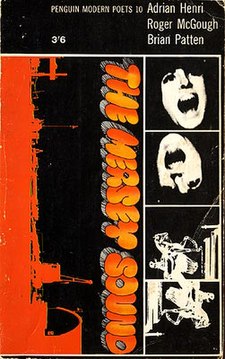

The Mersey Sound (anthology)

The Mersey Sound is an anthology of poems by Liverpool poets Roger McGough, Brian Patten and Adrian Henri first published in 1967, when it launched the poets into "considerable acclaim and critical fame".[1] It went on to sell over 500,000 copies, becoming one of the bestselling poetry anthologies of all time. The poems are characterised by "accessibility, relevance and lack of pretension",[1] as well as humour, liveliness and at times melancholy. The book was, and continues to be, widely influential with its direct and often witty language, urban references such as plastic daffodils and bus conductors, and frank, but sensitive (and sometimes romantic) depictions of intimacy.

History

[edit]The Mersey Sound is number 10 in a series of slim paperbacks originally published in the 1960s by Penguin in a series called Penguin Modern Poets. Each book assembled work by three compatible poets. Number 6, for example, contained poems by George MacBeth, Edward Lucie-Smith and Jack Clemo. The other books in the series were not given a specific title.

The first edition of The Mersey Sound contains 128 pages, the half-title page being number 1. Henri is first with 44 pages (30 poems), then McGough with 32 pages (24 poems) and Patten with 31 pages (26 poems).

A "revised and expanded" edition was published in 1974, with a cover showing an electric guitar and a total of 152 pages.

Another revised edition came out in 1983, by which time more than 250,000 copies of the two previous editions had been sold. The third edition has "Revised Edition" as a subtitle, but on the cover only, with a photograph of the three poets taken by Dmitri Kasterine. Extra poems, such as Henri's "The Entry of Christ into Liverpool," helped to take the total number of pages to 160, but some of the reprinted poems had been revised in the meantime, and some were omitted, such as McGough's "Why Patriots Are a Bit Nuts In the Head". The blurb mentions the revisions, but there is no explanation for the omissions. There was also the addition of short biographies of each poet.

Another book in the same format, and with complementary graphics, was also published in 1983, titled New Volume and with all new poems by each poet, and the same biographies as in the revised edition. Again the space is weighted in favour of Henri, at 57 pages, with McGough having 33 pages and Patten 35 pages, though they each have two more poems included than Henri, whose section includes longer sequences such as "From 'Autobiography'".

Both the revised and second revised issues are now out of print, the re-editing in these editions effectively superseded by more thorough collected editions of the poets' individual works.

To mark the 50th anniversary of its publication, the 2007 reissue (within the Penguin Modern Classics imprint, and subtitled "Restored 50th Anniversary Edition") reverted to the original 1967 text.

Poems

[edit]Henri took the title of the poem, "Tonight at Noon", from a Charles Mingus LP. He uses it three times in the poem, the first two to introduce a list of contradictions, such as "Supermarkets will add 3d EXTRA on everything" and "The first daffodils of autumn will appear/when the leaves fall upwards to the trees". Having set up this expectation, the poem ends poignantly with:

and

You will tell me you love me

Tonight at noon

McGough's "At Lunchtime A Story of Love" is based on then-current fears of a nuclear holocaust. The poet explains the world is going to end at lunchtime in order to persuade a passenger on the bus to make love with him. She did, but it didn't, and "Thatnight, on the bus coming home,/we were all alittle embarrassed..." (The joining of words to make a single word is a characteristic of McGough's work.) The poet "always/having been a bitofalad" then says, "it was a pity that the world didn't nearly/end every lunchtime and that we could always/pretend...", which they proceed to do. He sees the potential to change the world, when this ready excuse for shedding inhibitions and making love spreads, so that everywhere

people pretended that the world was coming

to an end at lunchtime. It still hasn't.

Although in a way it has.

All the poets are capable of a range of emotions and responses, but Patten is regarded as the most serious in tone of the three. "Party Piece" is the first poem in his section, where the poet suggests to a woman that they "make gentle pornography with one another", which they do. The ultimate unfulfillment of the encounter is captured when the poem ends:

And later he caught a bus and she a train

And all there was between them then

was rain.

There is a certain amount of interplay between the three poets. McGough's poem "Aren't We All" also describes a casual sexual encounter at a party with a rather more wry tone:

There's the moon trying to look romantic

Moon's too old that's her trouble

Aren't we all?

The cross-reference is overt on occasion. McGough has a six-line poem, "Vinegar", where he compares himself to a priest buying fish and chips, thinking it would be nice "to buy supper for two". Henri includes "Poem for Roger McGough", which describes a nun similarly thinking what it would be like to "buy groceries for two" in a supermarket.

Context

[edit]The three poets were active in "swinging" Liverpool at a time when it was a centre of world attention, due to the eruption of The Beatles and the associated bands, known generically as the "Mersey Sound", after which the book is titled.

Phil Bowen in A Gallery to Play To: The Story of the Mersey Poets considers that the poets were as central to their generation as the poets centred on W. H. Auden were to theirs. He distinguishes between them and other contemporary "underground" poets such as Michael Horovitz and Pete Brown, who modelled themselves and their verse forms on the American Beat Generation poets, whereas the Liverpool trio derived their major inspiration from the environment in which they lived. He even suggests that The Mersey Sound might not have been published at all, had it not been for the focus that Liverpool had generated musically.[1]

Contemporary effect

[edit]It has been said of the 1960s: "the rebirth of poetry then was largely due to the humour and fresh appeal of this collection."[2] The book had a magical effect on many people who read it, opening their eyes from "dull" poetry to a world of accessible language and the evocative use of everyday symbolism. Leading anthologist, Neil Astley, describes how he had been reading the classic poets at school in the 1960s, and one day his teacher read from The Mersey Sound: "That woke us up."[3] The same experience is described by a freelance writer Sid Smith years later in a 2005 blog, looking back at his first encounter with the book in 1968, when again a teacher read from it:

The cover design was a psychedelic beacon flashing at the outer edge of our black and white lives. The times were polarised and solarised and this small book was impossibly exotic and esoteric ...

During 1969 that slim volume was as well read as any of my Marvel and DC comics, space race encyclopedia or the Dr. Who annuals that never quite lived up to the show itself.

Of course I didn’t “get” most of what The Mersey Sound was about but that didn’t matter. It made me feel somehow connected to, well, whatever it was that I thought was going on out there in that wider, long-haired world that I intuitively knew I wanted to be part of.[4]

Legacy

[edit]The three poets in The Mersey Sound paved the way for later performance and "people's" poets, such as John Cooper Clarke, Benjamin Zephaniah, Linton Kwesi Johnson, Attila the Stockbroker, John Hegley and others who "have pursued the goal of creating poetry for a wide audience".[1]

The idea of titling after a river was later adopted by The Medway Poets in 1979. They read with Henri, McGough and Patten on occasion.

Paul Weller of The Jam has expressed his admiration for the poets, particularly Henri.[5] The second Jam album This Is the Modern World has a track with the same title as the Henri poem, "Tonight At Noon" and the lyrics are a collage tribute to Henri's poetry.

The book was one which stayed with some of its readers for years afterwards, and could help form bonds, as 1960s reader of it, Sid Smith, describes:

Flashing forward to the 90s and I’ve just met a woman called Debra at a party. We are introduced by a mutual friend and get talking. Somehow poetry comes into the conversation. “One of my favourite collections is The Mersey Sound” she tells me and in that moment I knew my life was going to change forever.[4]

As the early readers of the book got families of their own, they could find the simple language and rhyme of some of the poems suitable for bedtime reading for their children.[6] In addition all three poets went on to also write dedicated and successful books of children's poetry.

In 2002 the three poets were given the Freedom of the City of Liverpool.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "XIV Modern Literature, section 5", John Brannigan Accessed April 9, 2006

- ^ "Sixty after Sixty", Christine Bridgwood, West Midlands Libraries Accessed April 9, 2006 from the poetrysociety.org.uk

- ^ "Neil Astley : The StAnza lecture, 2005, section 10" Accessed April 9, 2006

- ^ a b "Love Is", Sid Smith's Bog Book Blog, September 7, 2005 Accessed April 9, 2006

- ^ Harris, John (3 February 2006). "The Jam? They were a way of life". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 March 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ "Book Review", Sue Lander, Bradworthy News, 2000 Accessed April 9, 2006