User:AmazingJus/sandbox/brummie

Grammar[edit]

Older speakers tend to use more of these grammatical features, where younger speakers mostly use phonological and intonational features in the sections described below.[1]

- Double negatives are typical in Brummie as with many other dialects around the world.[2] Syntactical examples include don't want none, hadn't got no, can't find none nowhere, hadn't got hardly any and without no.[3]

- Similarly, Brummie also utilizes double comparatives, such as more happier or more cuter (compare standard happier/cuter). [4] Note also bestest for best, badder/worser for worse and baddest/wors(t)est for worst.[5]

...

- Pronouns...

Contractions[edit]

Contractions in Brummie contain unique expressions for the area. ... Most involve negation particles.

| Brummie | Standard | Pronunciation | Example | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ain't | haven't | /ɪnt ~ ɛnt ~ æɪnt/ | I ain't seen 'er in donkey's years. | Used as a common vernacular in many other areas. Unique to Brummie though, when meaning "haven't", pronunciations range from from in't ~ en't ~ ain't.[6] |

| isn't/aren't | /æɪnt/ | She ain't joinin' us. | ||

| bain't | am not (c.f. Hiberno-English amn't) | /bæɪnt/ | I bain't doin' owt with me babby today. | Used only with the first person pronoun I. |

| dain't | didn't | /dæɪn(t) ~ dɪn/ | They dain't got no time for playin' with 'em. | |

| gonna | going to, gonna | We're gonna 'ave a bostin' jolly up at the park this weekend. | ||

| ne'er | never | /nɜː/ | I ne'er thought I'd see the day. | |

| worn't | wasn't | /wɔːnt/ | I worn't thinking a-gooin' up the pub today. | |

| wun't | won't | /wʊnt/ | She wun't be 'appy at all when she 'ears what 'appened 'ere. |

Morphophonology[edit]

- The past tense forms of strong verbs are often simplified. Examples include kept to kep', swept to swep' and wept to wep'.[7]

- Older Brummies often pronounce nouns ending in -ce with a /-z-/ in the plural form, where it would not be in the standard language. Eye dialect spellings that demonstrate this phenomenon include writing fazes instead of faces, plazes for places, and prizes for prices.[8]

- The third-person present of go, goes... [9]

- Several verb forms, including make, made and take, realise the vowel as monophthongal /mɛk, mɛd, tɛk/, similar to the monophthongisation of RP says or said.[10]

- The pronouns he, him, his, her, along with the related forms have, has and had are often orthographically represented with an apostrophe ('e, 'im, 'is, 'er, 'ave, 'as and 'ad respecitvely), reflecting the phenomenon of H-dropping (see below).[11]

Phonology[edit]

Consonants[edit]

- Like the West Midlands accents of the north, and many other Northern English accents, NG-coalescence is absent, with /ŋ/ being pronounced as [ŋɡ].[12][13]

- Word-final G-dropping is varied upon social class; with [ɪŋ] being favoured by middle-class speakers and [ɪŋɡ, ɪn] by the working class.[14]

- H-dropping is present, which mirrors many other working-class British accents.[15] It is, however, most consistent with function words, as mentioned above.

- Hypercorrection with /h/ commonly occurs with younger middle-class people as well as some older working class, with words such as April and orange being pronounced and represented as Hapril and horange. This is especially seen if the other person addressed to appears to be upper class.[16]

- Speakers also use the indefinite article an before words beginning with ⟨h⟩ such as an 'ouse. This is a further extension to standardized accents such as RP, where it is only used in learned terms such as hour or honest.[11]

- Th-fronting occurs for both /θ, ð/ to /f, v/ respectively with younger speakers, particularly working-class males. /θ/ especially occurs before /r/ at the beginning of a word (as in through) however, /ð/ is not fronted word-initially (e.g. this).[17] These phenomenon is also common with other regional British dialects.

- Under influence of Estuary English, T-glottalization occurs intervocalically and word-finally, albeit only in younger speakers.[18]

- The accent is non-rhotic, which means that the consonant /r/ is not pronounced at the syllable rime.[8] However, when as an onset, it is rendered as a single tapped /ɾ/ like of Scottish English varieties: the most prominent examples include intervocalically in disyllabic words, such as marry, perhaps (note the 'h' here is silent) and worry, as well as following a velar or bilabial stop in monosyllabic words, like bright or cream. Other onset environments are otherwise realized as /ɹ/.[19]

- Linking and intrusive R are likewise present with all other British dialects.[20]

- Realization of /l/ is identical to Recieved Pronunciation, where it is dark [ɫ] in the rime and light [l] elsewhere.[21]

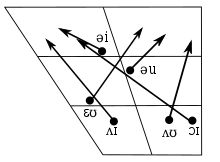

Vowels[edit]

Monophthongs[edit]

| Front | Central | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | long | ||

| Close | ɪ | iː | ʊ | uː | |

| Mid | ɛ | ɛː | ɜː | (ʌ) | ɔː |

| Open | a | ɒ | ɑː | ||

- The FLEECE is diphthongized,[23] though the exact quality varies based on description: Wells (1982) lists [ɪi~əi],[22] Thorne (2003) mentions [ɜi].[24]

- HAPPY is also diphthongal, however it can also be [iː].[25] Thorne (2003) mentions that this is mostly the case for younger speakers.[26]

- KIT is commonly a very close and front [ɪ̝],[27] although other sources claim an even closer and fronter [i] in stressed syllables, which is considered the most distinct phoneme in this dialect.[22][28] XXX states that [ɪ̝] occurs in unstressed syllables.

- The weak vowel merger is generally absent in Birmingham,[29] maintaining full vowels in places where RP has shifted towards a more reduced vowel quality; in RP, affixes such as -ace, -ate, -ily, -ity, -ible, -less and -let as well as the prefixes be-, de-, e- and re- have tended towards a reduced /ə/ during the 20th century[30] whereas Brummie consistently uses a full vowel [ɪ̝] in these morphemes. However, Thorne (2003) cites Gimson & Cruttenden (1994, pp. 98–101) on the word visibility as an exception to the rule, pronounced as [ˌvɪ̝zɪ̝ˈbɪ̝lətiː ~ -tɜi], where only the vowel on the penultimate syllable is reduced to [ə].[29] In RP, it is pronounced as /ˌvɪzəˈbɪləti/.

- In working class and older speech, LOT is typically /ʊ/, leading to a merger with FOOT/STRUT. However an RP-influenced /ɒ/ can be seen from younger or more upper-class speakers.[31][32]

- The LOT–CLOTH split is present in older Brummies, with words such as cough, cross and off using /ɔː/.[24][33] This feature mirrors conservative RP speech.

- The FOOT–STRUT split is absent like all of Northern England,[34] however, unlike Northern dialects, the vowel here is a more rounded and close [u̟][35] or slightly open [ɤ];[36] a sound which reflects Brummie's transitional region, mediating between [ʊ~ʌ].

- GOOSE, like FLEECE also varies in realization: [ʊu~əu][37] or [ɜu].[38] Older speakers may have an offglide of [uːə].[39] Some speakers also use this sound to merge with MOUTH (see #Diphthongs below).[39]

- Realization of NURSE is [ə̝ː~ɨ̝ː] according to Wells (1982)[40] or [ɜ̝ː] according to Thorne (2003). Older, more traditional realisations are fronter, ranging from [eə~œː~eː].[39][41] These are pronounced with the tongue closer to the mouth than other English accents such as RP ([ɜ̞ː]), however similar pronunciations can also be found in Australia and South Africa.

- In older Brummie accents, the CURE vowel has pronunciations varying between [ʊə~ʊæ̞~ɜʊæ̞], ranging from the least to the most broad.[42]

- The FORCE and CURE sets had [ɔː, uə] respectively, where the words paw, pour, poor would be said as [pɔː, pʌʊə, puːə] respectively. In more modern accents, there has been a shift towards a monophthongal realisation for both sets, leading to all three being pronounced as [pɔː].[43][44] The final element of the vowel is a lengthened [əː] before the morphemic suffixes -ed or -es and absent before the suffix -ing.[43]

- DRESS is centralised and raised [ɛ̝~e̞].[45]

- Word-final LETTER is typically more fronted compared to RP ([æ̞~ɛ]), although more middle-class speakers have an RP-influenced [ə].[46]

- When preceding the morphemic suffixes -ed or -es, it is a lengthened schwa [əː] similar to the CURE vowel.[47] Compare batter [ˈbæ̞tæ̞] with battered [ˈbæ̞təːd].

- The PALM vowel...

- TRAP, typical of northern English varieties, is a slightly lowered [æ̞], although it not as low as Scouse or Geordie [a̝], but is still distinct from to southern pronunciations such as RP [æ]. This highlights Birmingham's transitional nature between North and South England.[48]

- Due to Birmingham being in a transitional area, the trap-bath split is a complex issue. It is typically absent in most speakers[49] although some variation is noted.[50] Many Brummies generally pronounce aunt, half and laugh(-ter) with the lengthened BATH vowel, contrasting with words such as last, although older speakers may also use TRAP in these circumstances.[51][33][52] This in turn creates social stigma, where the TRAP vowel is often looked down upon such as the placename Edgbaston (see #Phonemic incidence below).[50]

Diphthongs[edit]

| Closing | Centring |

|---|---|

| ʌɪ | (ɪə) |

| (oɪ) | (ʊə) |

| ɒɪ | |

| æʊ | |

| ʌʊ |

- FACE has a more open onset, yielding [ʌɪ][36] or [æɪ],[53] similar to Cockney.

- PRICE and CHOICE are merged in the broadest accents so that line and loin sound the same.[54][55] Here, the diphthong commonly ranges from [oɪ~ɔɪ]; the most common realization being [ɔ̞ɪ].[10][36]

- Wells (1982) states that the offset of the MOUTH vowel can sometimes be reduced as in [æə].[22] Thorne (2003) suggests the onset is slightly less open compared to other dialects, rendering [ɛʊ]. For those who merge this vowel with GOOSE, the vowel's onset is also realized further back, as [ɜʊ].[42]

- The GOAT vowel is typically [ʌʊ].[56][36]

- Realisation of SQUARE is monothphongized and centralised [ɜː], which contrasts with southern British accents.[57]

Phonemic incidence[edit]

Birmingham has lexical peculiarities when it comes to pronunciation, usually retained by older speakers. Note that there are a handful of words that are pronounced in a non-standard way (e.g. baby /ˈbæbəi/) but are considered distinct dialectal words ('babby') in their own right; see #Lexicon below.

- Ad-, con-, ex- when unstressed are pronounced with their reduced forms (/əd-/, /kən-/, /əks/), contrasting with the full forms (/ad-/, /kɒn-/, /ɛks/) found in most areas north of Birmingham.[22]

- Been and seen is generally shortened to /bɪn, sɪn/, being homophonous to bin and sin respectively.[58][23]

- Bus is pronounced with a final voiced consonant (/bʊz/) without exception,[8] making it homophonous to buzz.

- Get can be pronounced as /ɡɪt/.[59]

- Girl varies in pronunciation between /ɡal ~ ɡɛl/.[60]

- Guernsey, meaning a woollen sweater, can have the first vowel be pronounced with /a/.[41]

- Home is /ʊm/ by older speakers.[9][61]

- Hoof, roof, spoon are pronounced with the long vowel /huːf, ɾuːf, spuːn/, unlike the typical northern /hʊf, ɾʊf, spʊn/.[60]

- One is pronounced as /wɒn/,[25] which contrasts with won (verb) /wʊn/.[62] This can be found in other varieties of British English as well.

- Tooth is pronounced /tuːθ~tʊθ/, ranging from the 'educated' south to the 'vulgar' north respectively;[25] this exhibits Birmingham's transitional area between the southern and northern dialects.[63]

- Was has pronunciations varying from /wɒz~wʌz~wʊz/.[31]

- Week is shortened as /wɪk/, homophonous to wick and creating a minimal pair with weak (adjective) /wiːk/.[38][64]

- Worse/worst is typically pronounced as /wʊs(t)/.[60]

- Likewise, older Brummies will also pronounce first as /fʊst/.[60]

Shibboleths also exist which distinguish people from different districts or social classes:

- Edgbaston: A middle-class district, the vowel in second syllable is pronounced by locals and other middle-class speakers as /ɑː/ or /ə/. The working class pronounce it as /æ/, signifying that those speakers cannot live there.[65]

- Solihull: Middle-class speakers pronounce the first vowel as GOAT, whereas working-class speech use LOT.[46]

Phonological processes[edit]

- Nasalization is heavily exaggerated and stigmatised.[66]Add thorne ref from later chapters Nasality in Brummie is often stronger than in the RP variety, whereas in RP a vowel can only be nasalized before a nasal consonant (i.e. /m, n, ŋ/), Brummie can also nasalize vowels after the aforementioned consonants and even independently in the strongest accents. This realization is often compared to other regional British accents, for example singer is rendered as [ˈsɪ̝̃ŋɡæ], but compare also Nick [nɪ̝̃k] and kick [kɪ̝̃k].[67]

- Elision of consonants occurs similar to many colloquial accents of English...

Prosody[edit]

Lexicon[edit]

Brummie has a number of traditional words and expressions that ... which include:

- babby — representing an older pronunciation of baby; more common in the west of Birmingham.[10]

- bostin — used to refer to anything positively (i.e. 'great' or 'awesome'); based on the verb boast.[68]

- boughten — something purchased rather than homemade; used mainly by older speakers.[69]

- gal, gel — eye dialect spellings of 'girl'.[60]

- mek/med — to 'make'/'made' (past tense of 'make')[10]

- miskin — a dustbin/garbage can.[70]

- suff — a drain.[70]

References[edit]

- ^ Thorne (2003), pp. 64–65.

- ^ Thorne (2003), p. 65.

- ^ Thorne (2003), pp. 65–66.

- ^ Thorne (2003), p. 66.

- ^ Thorne (2003), p. 67.

- ^ Thorne (2003), p. 74.

- ^ Thorne (2003), p. 124.

- ^ a b c Thorne (2003), p. 127.

- ^ a b Thorne (2003), p. 114.

- ^ a b c d Thorne (2003), p. 111.

- ^ a b Thorne (2003), p. 119.

- ^ Thorne (2003), p. 212.

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 365.

- ^ Thorne (2003), p. 121.

- ^ Thorne (2003), pp. 118–119.

- ^ Thorne (2003), p. 120.

- ^ Thorne (2003), pp. 124–125.

- ^ Thorne (2003), pp. 125–126.

- ^ Thorne (2003), p. 128.

- ^ Thorne (2003), pp. 136–7.

- ^ Thorne (2003), p. 126.

- ^ a b c d e f Wells (1982), p. 363.

- ^ a b Clark (2004), p. 160.

- ^ a b Thorne (2003), p. 103.

- ^ a b c Wells (1982), p. 362.

- ^ Thorne (2003), p. 105.

- ^ Thorne (2003), p. 90.

- ^ Gimson (2014), p. 115.

- ^ a b Thorne (2003), p. 91.

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 296.

- ^ a b Thorne (2003), p. 102.

- ^ Clark (2004), p. 157.

- ^ a b Clark (2004), p. 158.

- ^ Thorne (2003), p. 99.

- ^ Thorne (2003), p. 100.

- ^ a b c d Wells (1982), p. 364.

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 359, 363.

- ^ a b Thorne (2003), p. 106.

- ^ a b c Thorne (2003), p. 107.

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 360–361, 363.

- ^ a b Clark (2004), p. 159.

- ^ a b Thorne (2003), p. 115.

- ^ a b Thorne (2003), p. 116.

- ^ Wells (1982), pp. 364–5.

- ^ Thorne (2003), p. 89.

- ^ a b Thorne (2003), p. 97.

- ^ Thorne (2003), pp. 98–99.

- ^ Thorne (2003), p. 93.

- ^ Thorne (2003), p. 94.

- ^ a b Thorne (2003), p. 96.

- ^ Thorne (2003), p. 95.

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 354.

- ^ Thorne (2003), p. 110.

- ^ Thorne (2003), p. 112.

- ^ Clark (2004), p. 164–5.

- ^ Thorne (2003), p. 113.

- ^ Thorne (2003), p. 117.

- ^ Thorne (2003), p. 92.

- ^ Clark (2004), p. 155.

- ^ a b c d e Thorne (2003), p. 109.

- ^ Clark (2004), p. 163.

- ^ Thorne (2003), p. 101.

- ^ Thorne (2003), pp. 100–101.

- ^ Clark (2004), p. 161.

- ^ Thorne (2003), pp. 96–97.

- ^ Thorne (2003), pp. 132–134.

- ^ Thorne (2003), p. 130.

- ^ Thorne (2003), pp. 76–77.

- ^ Thorne (2003), p. 76.

- ^ a b Thorne (2003), p. 81.

Bibliography[edit]

- Clark, Ursula (2004), "The English West Midlands: phonology", in Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive (eds.), A handbook of varieties of English, vol. The British Isles, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 140???, ISBN 3-11-017532-0

- Clark, Urszula (2013), West Midlands English: Birmingham and the Black Country, Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 0748685804

- Elmes, Simon (2006), Talking for Britain: a journey through the voices of a nation, Penguin

- Gimson, Alfred Charles (2014), Cruttenden, Alan (ed.), Gimson's Pronunciation of English (8th ed.), Routledge, ISBN 9781444183092

- Thorne, Stephen (2003), Birmingham English: A Sociolinguistic Study, University of Birmingham

- Wells, John C. (1982), Accents of English, Vol. 2: The British Isles (pp. i–xx, 279–466), Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511611759, ISBN 0-52128540-2