User:ClemRutter/Translations

Bifilar Sundial- to translate[edit]

Inventé en 1922 par le mathématicien allemand Hugo Michnik, le cadran bifilaire est un modèle de cadran solaire qui présente la particularité d'indiquer l’heure par l'intersection de l’ombre de deux fils perpendiculaire au plan du cadran et non sécants, formant entre eux un certain angle (droit ou non). Il existe plusieurs possibilités de cadrans bifilaires

Cadran bifilaire horizontal[edit]

C'est le modèle qu'a découvert et étudié Hugo Michnik.

Un premier fil est orienté Nord-Sud et est situé à une distance constante du plan horizontal du cadran.

Un second fil est orienté Est-Ouest et est situé à une distance constante du plan (remarquer que est perpendiculaire à et est situé dans le plan du méridien).

Appelons respectivement et la projection des fils et sur le plan , et leur intersection.

Définissons pour axe des abscisses Ox la droite orientée vers l'Est, et pour axe des ordonnées Oy la droite orientée vers le Nord.

On peut montrer que si la position du soleil dans le ciel est connue et définie par ses coordonnées horaires et (respectivement angle horaire et déclinaison), alors les coordonnées et du point , intersection des ombres des 2 fils sur le plan du cadran, valent respectivement :

étant la latitude du lieu où est situé le cadran.

En éliminant la variable entre les deux relations précédentes, on obtient une équation reliant et et qui donne, en fonction de la latitude et de l'heure solaire (qui n'est autre que l'angle horaire du soleil), l'équation de la courbe horaire associée à une heure solaire donnée ; sous sa forme la plus simple à interpréter, cette équation peut s'écrire :

Cette relation montre que les courbes horaires sont des segments de droite et que les droites qui les portent passent toutes par le point de coordonnées :

En outre, si l'on s'arrange pour que les deux hauteurs et soient telles que l'on ait :

alors l'équation des lignes horaires s'écrit très simplement :

ce qui signifie qu'à tout moment, l'intersection des ombres des 2 fils sur le plan du cadran est telle que l'angle est égal à l'angle horaire du soleil et donc à l'heure solaire.

Ainsi, la particularité remarquable de ce type de cadran solaire bifilaire horizontal (qui respecte la condition ) est que les courbes horaires correspondant à une heure solaire donnée sont des demi-droites passant toutes par le point et que les 13 demi-droites correspondant aux heures successives 6h, 7h, 8h, 9h ... 15h, 16h, 17h, 18h sont régulièrement espacées d'un angle constant de 15°. Cette propriété s'appelle l'homogénéité des lignes horaires (suivant la terminologie proposée par Dominique Collin).

Un tel cadran bifilaire (horizontal et respectant la condition ) présente une autre propriété remarquable : il peut être déplacé le long d'un même parallèle (latitude constante) sans nécessiter la moindre modification dans le tracé des lignes horaires et des arcs diurnes.

Cadran bifilaire vertical[edit]

Dominique Collin a cherché à étudier toutes les variantes possibles de cadran bifilaire et s'est spécialement intéressé au cas d'un cadran bifilaire à plan vertical, puisque c'est, dans le cas des cadrans solaires classiques, le type le plus fréquent.

Il a établi que l'on peut concevoir un cadran bifilaire vertical dans lequel les fils sont, comme dans le cas particulier étudié par H. Michnik, parallèles au plan du cadran, sans être nécessairement orthogonaux ; plus précisément, il a montré que la propriété d'homogénéité des lignes horaires reste conservée si l'on respecte deux conditions qui s'expriment par deux formules mathématiques (liées entre elles) :

- l'une concerne l'angle que font entre elles les directions des deux fils (angle qui est droit dans le cas étudié par H. Michnik)

- l'autre concerne les distances respectives des 2 fils au cadran.

Les formules obtenues ne sont pas identiques à celles établies par Michnik, même si l'on choisit de garder les fils perpendiculaires entre eux (ce qui s'explique par le fait de la position différente du cadran dans l'espace).

Ce cadran bifilaire généralisé peut être posé sur un mur vertical d'orientation quelconque mais, en ce qui concerne le tracé des lignes horaires homogènes, Dominique Collin suggère de ne les dessiner que si ce mur est orienté à peu près vers le sud (cadran vertical pas trop déclinant) ; sinon, outre que le tracé général est peu esthétique, la lecture de l'intersection des ombres des 2 fils est trop imprécise.

Cadran bifilaire incliné déclinant[edit]

Ce type de cadran n'a pas été étudié de façon aussi systématique que celui des cadrans verticaux mais il semble, d'après F. W. Sawyer (voir la référence ci-dessous) que l'on puisse conserver la propriété d'homogénéité des lignes horaires : il existe, comme dans le cas des cadrans bifilaire verticaux, deux relations à respecter portant sur l'orientation et la position des fils, mais celles-ci restent toutefois à établir...

Bibliographie[edit]

- H. Michnik, Theorie einer Bifilar-Sonnenuhr, Astronomishe Nachrichten, 217(5190), p.81-90, 1923

- Frederick W. Sawyer, Bifilar gnomonics, JBAA (Journal of the British Astronomical association), 88(4):334–351, 1978

- D. Collin. Les cadrans solaires verticaux à deux gnomons rectilignes quelconques [généralisation des cadrans bifilaires de Michnik], Observations & Travaux, n°55, pp.12–31, décembre 2003.

Voir aussi[edit]

Articles connexes[edit]

Liens externes[edit]

- (in French) Les Cadrans de Constant, Exemples de cadrans bifilaires

Bifilaire Sonnenuhr[edit]

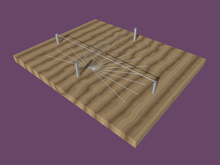

miniatur|Horizontale Bifilar-Sonnenuhr mit homogenen Stundenlinien

[[Datei:Bifilar-Sonnenuhr.jpg|miniatur|Horizontale Bifilar-Sonnenuhr mit homogenen Stundenlinien (Nachmittag), φ = 47°, N/S-Faden = Blech-Oberkante,

Sonnen/Schatten-Strahlen markiert

(rot: Tagesbahn (Sommersonnenwende), grün: Stundenlinie (II Uhr))]]

Die Bifilar-Sonnenuhr ist eine Sonnenuhren-Bauart, die der Mathematiklehrer Hugo Michnik 1922 vorstellte.[1]

Als Schattenwerfer dienen zwei sich kreuzende, aber nicht schneidende Stäbe oder Fäden – Michnik nannte diese Sonnenuhr deshalb Bifilar-Sonnenuhr. Die Uhrzeit wird auf dem Zifferblatt vom Schnittpunkt der beiden Linienschatten angezeigt. Die hier angewendete Projektion ist eine Verallgemeinerung der bei Sonnenuhren mit Nodus als Schattenwerfer zugrunde liegenden gnomonischen Projektion.

Michnik zeigte, dass das Bifilar-Prinzip für alle von Nodus-Sonnenuhren bekannten Möglichkeiten der Anzeige geeignet ist, also

- für den Stundenwinkel der Sonne als Uhrzeit,

- für die Deklination der Sonne, weil der Tagbogen als Funktion der Jahreszeit ersichtlich ist,

- für die Anzeige von Sternzeit, babylonischer und italienischer Stunden

- sowie für die Anzeige temporaler Stunden.

Die am häufigsten gebaute Bifilar-Sonnenuhr ist jene mit homogenen Stundenlinien (siehe Abbildungen). Die Verlagerung der Schattenbildung vom Punkt (Nodus) auf zwei relativ zueinander und zum Zifferblatt in vielfältiger Weise positionierbarer Fäden erlaubt, eine Anordnung zu finden, bei denen die Stundenlinien wie die Großkreise mit der Sonne am Himmel in 15°-Winkelschritten aufeinander folgen. Beide Fäden sind zum Zifferblatt parallel. Der nähere Faden (Abstand ) hat Ost-West-Ausrichtung, der entferntere (Abstand ) bildet mit dem näheren in der orthogonalen Parallelprojektion auf das Zifferblatt einen rechten Winkel. Die bereits von Michnik für homogene Stundenlinien angegebene Bedingung lautet:

- .

Hierbei ist ist die geografische Breite des Aufstellungsortes der Sonnenuhr.

Die Vielfalt, wie sich die Fäden anordnen lassen, ist Anreiz für eine große Zahl experimenteller Bifilar-Sonnenuhren. In der Regel wird damit eine bestimmte einzelne Anzeige möglich, nicht aber eine einfach anzufertigende Sonnenuhr geschaffen, die universell wie auch die Bifilar-Sonnenuhr mit homogenen Stundenlinien ist.[2] Letztere hat gegenüber der Sonnenuhr mit Nodus den Nachteil der größeren Ost-West-Ausdehnung. Wegen der damit verbunden früheren Unschärfe des Schattenkreuzes ist die Anzeige am Morgen und am Abend eingeschränkter als bei der mit Nodus.[3]

Einzelnachweise[edit]

- ^ H. Michnik: Theorie einer Bifilar-Sonnenuhr. In: Astronomische Nachrichten. 217, Nr. 5190, 1922, S. 81 (fakesimile);

vom selben Autor: Untersuchung der temporären Stundenlinien antiker Sonnenuhren. In: Jahresberichte des Königlichen Gymnasiums zu Beuthen, 1913-14, Beilage, Teubner, Leipzig 1914 (Digitized) - ^ Karl Schwarzinger: Orologio bifilare - Bifilare Sonnenuhr. In: Sonnenuhren Bild 38/1 7. November 2001.

- ^ Siegfried Wetzel: Sonnenuhr und Mathematik. (Abschnitt: 4. Die gnomonische und die Bifilar-Sonnenuhr).

de:Vorlage:Navigationsleiste Sonnenuhren Kategorie:Sonnenuhr

Reloj[edit]

The bi-filar sundial is typically a horizontal sundial with two wires passing over it, the intersection of the shadows thrown by these wires indicates the time. This replaces the conventional gnomon. The dial was invented in 1922 by the german mathematician Hugo Michnik.[1] The first design published in his paper, showed two rods that crossed orthogonally (one going north south, and the other east west): he used the methods of analytical geometry to derive the equations for the shadow and the lines on the base-plate. Later he realised the method could be extended and the equations could be generalised .[2] An interesting property of this dial is that base plate markings become that of a Equatorial sundial when the ratio of wires is the same as the sine of the latitude.

Developments[edit]

After the original discovery, numerous mathematical studies have been made into the properties of bifilar sundials: changing the position of the wires so they are non-orthogonal, and the positioning of the base-plate from horizontal to vertical. The introduction of computers has created new interest amongst mathematicians in investigating the properties of these dials.

Horizontal bifilar sundial[edit]

The Horizontal bifilar sundial was the first dial investigated by Hugo Michnik in 1922. The first wire is at a constant height of above the horizontal plane. del cuadrante solar, and is orientated in a North/South direction parallel to the meridian. The second wire is at a constant height of above the horizontal plane. and is orientated perpendicular to the first, that is to say, orthoganlly in a east-west dirrection.

y que pasa simultáneamente por la intersección de los hilos.

The suns ray's are expressed using the horizontal coordinate system y su disposición a lo largo del día se expresa en función del ángulo horario y la solar declination . Es evidente que la intersección de este rayo con el plano del cuadrante del reloj proporciona un punto de coordenadas :

De estas dos fórmulas se puede despejar aquellos términos que contienen la y se resumen en una sola ecuación escrita como:

Esta relación, debido a la proporcionalidad lineal entre las coordenadas y muestra que las curvas horarias de este reloj son líneas rectas que pasan por el punto de coordenadas:

Cuadrante bifilar horizontal[edit]

Este fue el primer desarrollo realizado por Hugo Michnik en 1922, el reloj se compone de dos hilos tirantes rectos. Un primer hilo se encuentra elevado a una cota constante del plano horizontal del cuadrante solar, y se orienta en la dirección Norte-Sur paralela al meridiano del lugar. Un segundo hilo se siua a una cota constante del plano horizontal del cuadrante solar y está orientado perpendicularmente al anterior, es decir siguiendo la dirección Este-Oeste. El problema a resolver es encontrar una línea recta que representa el rayo solar y que pasa simultáneamente por la intersección de los hilos.

Este rayo solar se expresa en coordenadas horizontales y su disposición a lo largo del día se expresa en función del ángulo horario y la declinación solar . Es evidente que la intersección de este rayo con el plano del cuadrante del reloj proporciona un punto I de coordenadas :

De estas dos fórmulas se puede despejar aquellos términos que contienen la y se resumen en una sola ecuación escrita como:

Esta relación, debido a la proporcionalidad lineal entre las coordenadas y muestra que las curvas horarias de este reloj son líneas rectas que pasan por el punto de coordenadas:

Referencias[edit]

- ^ H. Michnik, (1922), "Astronomische Nachrichten", Volume 217, Issue 6, págs. 81–90

- ^ Collin, D, (2000), Théorie sur le cadran solaire bifilaire vertical déclinant, Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Vol. 94, p. 95

Véase también[edit]

Textilfabrik Cromford[edit]

The Textilfabrik Cromford in Ratingen, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany was built in 1783 by Johann Gottfried Brügelmann. It was the first Fabrik on the European mainland. Today it is an industrial museum specialising in textile history.

History[edit]

Brügelmann, came from a rich Elberfelder trading family. He heard of the Waterframes, an invention of Richard Arkwright in the Derbyshire village of Cromford, in the early 1770s – during a long stay in Basel. On his return to Wuppertal the cotton market was booming, it was impossible to fufil the demand. Brügelmann recognised the potential that Arkwright's mechanising of the labour intensive Spinning process offered. As a rule of thumb each weaver needed all the yarn that 10 hand-spinners could produce.[1]

Richard Arkwright vigorously guarded his patent. He would not reveal how the water frame worked, keeping the details secret. Furthermore, the British Government saw this as a state secret that must not be allowed to leave the country..[2]

Brügelmann obtained a model of the Waterframe in 1783. He had already worked unsuccessfully for six years with experts from Siegerland to discover the workings of an Arkwright Carding machine: this made the sliver that was needed for the waterframe. It is unclear whether he got a model of this too, family papers suggest that he smuggled a spinner from Cromford over to Germany, with a collection of the parts needed to reconstruct the carding engine. In a letter to Count Karl Theodor he wrote he had a friend in England who had sent him the parts needed.[2] Though it is possible that he worded this letter carefully, not leaving himself open to charges of Industrial espionage.

Construction[edit]

Brügelmann looked for a suitable factory in the neighbourhood. In Wuppertal he was frustrated by a cartel of traders, with their rights to Garnnahrung" and subsequent trading restrictions. [a] Eventually he found a deserted oil-mill in the village of Eckamp. This has water extraction rights on Angerbach. It was just outside the town walls of Ratingens, next to the moated castle of Haus zum Haus. The Count gave him 12 year exclusive rights to construct and operate a cotton-spinning mill in this building.(Brügelmann had sought 40 year priviledges, to compenste him for the initial investment). Recruiting a work-force in poverty stricken Ratingens was relatively simple: few said no to work and there was none of the rioting by weavers seen earlier in the decade in Elberfeld and Barmen. [2]

He built two spinning halls, alongside the River Angerbach, hired further English trained cotton workers to construct and operate water frames. In 1784, production started. All the machines were powered by waterwheels. He called the mill after the Derbyshire town. Today the area of Ratingen, between Hauser Ring, Mülheimer Straße and Junkernbusch is called "Cromford".

The business became prominent in the area: an imposing five storey factory building was erected, and then a luxurous villa for the owner costing 20.000 Reichstaler, (Herrenhaus in German). It also had a Baroque park, with an English Garden, laid out by Maximilian Friedrich Weyhe. Ten years after the mill opened, it was employing 400 workers; at that time an unprecedented number for a business. It peaked in 1802 at 600, then the exclusive privileges expired, and other manufactures built bigger mills.

After the death of Brügelmann his sons continued the business. The business continued to expand and was still operating in the 1960s when the mill fell silent.

Current usage[edit]

The additional modern buildings were demolished in the 1980s and replaced with housing. However the Herrenhaus, "Villa Cromford", and the original 5 storey factory, "Hohe Fabrik" remain.

In 1983 an archaeological study was commissioned, and the important industrial location was documented. Thew buildings became part of the Rheinischen Industriemuseums.[3] Exact working replicas of all the important cotton machines from this time were installed in the old mill. All can be powered from the central waterwheel, and they can be seen working. Exhibitions on the history of the mill, the processes and the working conditions (including child labour) are on display.

The Garden Room of the Villa Cromford is used as a wedding venue.

References[edit]

- Foot notes

- Notes

- ^ Eckhard Bolenz (2000), Bolenz; et al. (eds.), "Vom Ende des Ancien régime bis zum Ende des Deutschen Bundes (ca. 1780–1870)", Ratingen. Geschichte 1780 bis 1975 (in German), Essen: Klartext Verlag, ISBN 3-88474943-9

{{citation}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|editor-surname1=(help); Unknown parameter|Comment=ignored (help) - ^ a b c http://www.guelcher-chronik.de/Stichworter/Johann_Gottfried_Brugelmann/johann_gottfried_brugelmann.html

- ^ offizieller Name: „LVR-Industriemuseum, Schauplatz Ratingen, Textilfabrik Cromford“ (Norbert Kleeberg (7 Februar 2009), "Krach um Cromford", Rheinische Post (in German)

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link))

Weblinks[edit]

51°18′21″N 6°51′11″E / 51.305833°N 6.853056°E

Ratingen Kategorie:Bauwerk in Ratingen Kategorie:Ehemaliges Unternehmen (Nordrhein-Westfalen) Kategorie:Ehemaliges Unternehmen (Fadenbildung) Kategorie:Museum im Kreis Mettmann Kategorie:Baudenkmal in Ratingen de:Vorlage:Navigationsleiste Rheinisches Industriemuseum

Possible to form URL to download article source directly?[edit]

Given a specific article title, say Boekenweek, is it possible download its text source directly? I was thinking along the lines of by adding to the article's URL. Maybe there's better way. Jason Quinn (talk) 22:52, 16 December 2014 (UTC)

When you say "text source" do you mean wikitext, parsed text (what renders on the page when reading), or raw HTML? — Technical 13 (e • t • c) 22:55, 16 December 2014 (UTC) Wikitext. Basically the contents of the edit window. Jason Quinn (talk) 23:12, 16 December 2014 (UTC) You can play around in the ApiSandbox. A place to start might be https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special:ApiSandbox#action=query&prop=revisions&format=json&rvprop=content&rawcontinue=&titles=Boekenweek - Good luck! — Technical 13 (e • t • c) 23:29, 16 December 2014 (UTC)

@Jason Quinn: use the basic URL http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?action=raw&ctype=text/plain&title= and append the page name, with spaces replaced by underscores - i.e. the URL http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?action=raw&ctype=text/plain&title=Wikipedia:Village_pump_(technical) will return the source for this page. --Redrose64 (talk) 00:28, 17 December 2014 (UTC)