User:Cplakidas/Sandbox/Melas

Pavlos Melas Παῦλος Μελᾶς | |

|---|---|

Pavlos Melas in uniform as an artillery second lieutenant of the Greek army | |

| Nickname(s) | Mikis Zezas |

| Born | 10 April [O.S. 29 March] 1870 Marseilles, France |

| Died | 26 October [O.S. 13 October] 1904 (aged 34) Statitsa, Ottoman Empire (now Melas, Greece) |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1891–1904 |

| Rank | Second lieutenant |

| Battles/wars | |

| Alma mater | Hellenic Army Academy |

| Spouse(s) | Natalia Dragoumi-Mela |

| Relations | Michail Melas (father) Vasileios Melas (brother) Anna Mela-Papadopoulou (sister) Natalia Mela (granddaughter) Ion Dragoumis (brother-in-law) |

| Other work | Member of the Ethniki Etaireia Member of the Macedonian Committee |

Pavlos Melas (Marseilles, 10 April [O.S. 29 March] 1870[1] – Statista, 26 October [O.S. 13 October] 1904) was a Greek military officer and one of the protagonists of the Macedonian Struggle.

Pavlos Melas was born in France in 1870, but moved with his family to Athens four years later. His father, the wealthy merchant Michail Melas, was an ardent supporter of Greek irredentism, and the young Pavlos grew up in a atmosphere charged with its ideals. He studied at the Hellenic Army Academy, became an officer, and married Natalia Dragoumi, daughter of the prominent politician Stefanos Dragoumis. The couple had two children. In 1894, Melas was among the founders the nationalist and irredentist organization Ethniki Etaireia, of which he was an active member, notably helping organize the sending of Greek irregulars into Ottoman-ruled Macedonia in spring 1897. This contributed to the outbreak of the Greco-Turkish War of 1897, which Greece lost disastrously; his father died shortly after of sorrow for the defeat.

After the dissolution of the Ethniki Etaireia in 1900, through the Dragoumis family Melas became involved in the Macedonian Question, and the emerging rivalry between Greece and Bulgaria. In cooperation with his brother-in-law Ion Dragoumis, Melas became one of the initiators of the Macedonian Struggle, supporting Greek claims in Macedonia with weapons and men. In March 1904, as the ethnoreligious tensions reached new heights following the Ilinden Uprising the previous year, Melas was one of four army officers selected by the Greek government for a reconnaissance tour in western Macedonia. On their return, the expedition members disagreed on the necessity and usefulness of sending armed groups from Greece, with Melas advocating for it, especially after a private visit to Kozani and Siatista in July, which convinced him to become personally involved in the area. In August he was named chief of all Greek groups in the area of Kastoria and Monastir by the newly founded Macedonian Committee, and led an armed band into Macedonia under the nom de guerre Mikis Zezas.

Melas' group toured the non-Greek-speaking villages of the region, pursuing their rivals, the komitadjis of the pro-Bulgarian IMRO, forcing Exarchist villagers to 'return' to the allegiance of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople and thus identify with the Greek cause, and using funds provided by the Macedonian Committee to establish a support network for the Greek armed groups in the region. On 26 October [O.S. 13 October] 1904, while at the village of Statista, where he hoped to meet the next day with another Greek armed group led by Efthymios Kaoudis and Pavlos Kyrou, his band was attacked by a detachment of the Ottoman army, in the mistaken assumption—engineered by the IMRO chieftain Mitre the Vlach—that they were komitadjis. Melas was wounded and died in unclear circumstances; different accounts survive as to the cause of his wounding and death. His head was cut off, but eventually was rejoined with his corps and buried at Kastoria.

The actual results of Melas' military activity were meagre on the ground, but his death made him a symbol to his cause. The death of a well-known scion of a wealthy Athenian upper-class family as a guerrilla, in the traditions of the klephts of the Greek War of Independence, shocked Greek public opinion and mobilized widespread support for the Macedonian Struggle, which was inextricably linked with Melas' name. Later during the 20th century, and especially after the Greek Civil War, Melas became a symbol for the right-wing, anti-communist 'national-mindedness' (εθνικοφροσύνη). His life was romanticized in novels, often by his relatives, and in film. In Greece he is still revered as a national hero, a defender of the Greekness of Macedonia. His name has been given to the village of Statista, where he was killed, and to a municipality of Thessaloniki.

Early life and family

[edit]Pavlos Melas was born in Marseilles in southern France, on 10 April [O.S. 29 March] 1870 as one of seven children of Eleni Voutsina, a daughter of a wealthy merchant hailing from Kefallonia, and the Epirote merchant Michail Melas.[2][3] The Melas family was an important merchant family hailing from Pogdoriani (modern Parakalamos), where ruins of a tower house belonging to the family survive.[4]

The Melas family settled in Athens, capital of the Kingdom of Greece, in 1874. The family house, on the central Panepistimiou Street, now houses the Athens Club.[5] Following the example of other wealthy entrepreneurs of the Greek diaspora, Michail Melas himself moved to Athens in 1876, and made it the seat of his enterprises.[6] He too espoused the irredentist Megali Idea concept,[3] which aimed to expand the small Greek kingdom to cover all regions where Greeks lived.[7] After moving to Athens he developed significant charitable and nationalist activity;[6] in 1878 he was treasurer of the Ethniki Amyna (lit. 'National Defence'), an organization promoting irredentism in Epirus and Thessaly, as well as Crete. The elder Melas also entered politics: in 1890 he was elected a member of the Hellenic Parliament, and in the year after he became Mayor of Athens.[8]

In this spirit, Pavlos was named after a forebear who had been killed at the Fall of Missolonghi during the Greek War of Independence,[9] while as a boy he was imbued with his father's ideals, and often imagined himself becoming a guerrilla; at one time he accidentally discovered in their home guns that were to be clandestinely shipped to Cretan insurgents.[3] At the time, scions of Greek bourgeois families usually followed either legal or military careers, and Pavlos chose the latter.[9] He began his five-year education at the Hellenic Army Academy in September 1886, graduating as an artillery second lieutenant in 1891.[3]

In the same year Melas met Natalia Dragoumi,[10] daughter of Stefanos Dragoumis, a politician and former Foreign Minister of Greece hailing from Vogatsiko in western Macedonia.[8] Melas and Dragoumi married in October 1892,[10] and had two children: a son, Michail (usually known as "Mikis"), in 1894, and a daughter, Zoi, in 1898.[11][12] The couple was complementary: Melas was an intensely affectionate father, not hesitating to display a childlike behaviour even in front of strangers, and appreciated his wife's level-headed advice, while Natalia was attracted to this more child-like character and supported him in his decisions. Melas at times did not consider himself worthy of playing the role of her protector.[13]

In the early 1890s, Melas became a passionate amateur photographer, one of the first in Greece, capturing scenes of his family and daily life, including the first modern Olympic Games, held in Athens in 1896.[14] In 1894 the family built a summer residence in Strofyli, in the leafy northern Athenian suburb of Kifissia. In 1903, Melas resolved to move his main residence there, but did not live to carry this out.[15]

Involvement in the Ethniki Etaireia and the Greco-Turkish War of 1897

[edit]In August 1984, Melas took part, along with 85 other officers and some privates, in the destruction of the offices of the liberal Akropolis newspaper in Athens. The newspaper had previously published a front-page article excoriating the authoritarian tendencies of the officer corps and questioning its very utility, after three officers had beaten up a citizen for little cause. All officers involved in the event were court-martialled, but the warrants issued for their arrest were never carried out, and they were exonerated by the court-martial on 24 September.[16][17] In November of the same year, fourteen of these officers, on the initiative of the second lieutenant Nikostratos Kalomenopoulos, founded the Ethniki Etaireia (lit. 'National Society').[18][19] Through this clandestine, conspiratorial organization, young officers sought to answer the criticism of their role in society, as well as provide an irredentist outlet for the political impasse after the Greek state bankruptcy of 1893.[20][21][22] Melas, who at that time was serving in the Military Geographical Service at Myloi,[19] joined the Ethniki Etaireia early on, with membership number 25.[19][23] Apart from being one of its founding members,[19] Melas was also one of the most active ones, especially in the establishment of new branches in the provinces, and in ensuring their uninterrupted contact with the organization's leadership in Athens.[24] Melas tasked Ioannis Metaxas, the future general and dictator, who at that time was an officer at Nafplio, to expand the organization's network in the Peloponnese.[19] From September 1895 onwards, the Ethniki Etaireia opened its ranks to include not only senior officers but also civilians; by early 1896 it numbered 3,185 members and enjoyed great influence in Greek society, increasingly acting independently of the Greek government.[25] Melas' father also became a member of the Ethniki Etaireia; in 1897 he was placed in charge of a public fundraiser for the group,[6] whose proceeds were intended for the purchase of arms.[19]

Reacting to the sending of guerrillas organized by Bulgaria into Ottoman-ruled Macedonia, in July–October 1896 the Ethniki Etaireia sent volunteer irregular forces of its own into Macedonia, but withdrew them after the negative reaction of the Greek government.[22][26][27] On 31 January 1897, Melas, then serving as head of the guard at the University of Athens, was abruptly recalled to the artillery barracks.[28] The reason was that the Greek government, under Theodoros Diligiannis, had resolved to send an expeditionary force to Crete, under Colonel Timoleon Vassos. The government had been extremely reluctant to get drawn into the troubles on the island that had begun in 1895, and was aware that the Great Powers were vehemently opposed to any Greek involvement there, but finally succumbed to the pressure of public opinion and organizations like the Ethniki Etaireia, which pressed for the union of the island with Greece.[29][30] To Melas' disappointment, his unit—a field artillery battery commanded by Prince Nicholas, the third-born son of King George I—was not to be included in the expeditionary force, but on the next day the unit received orders to move to Thessaly, via ship from Piraeus to Volos and thence by rail to Larissa.[31] Melas left his unit at Larissa and returned to Volos, from where, with the tacit approval of his superiors, he organized a 55-wagon train transporting irregulars recruited by the Ethniki Etaireia to the Greco-Ottoman border.[32] Melas disobeyed an order by his superior commander, Nikolaos Zorbas, to return to Larissa, arriving there two days late, which led to him being imprisoned until 5 April.[33] The guerrillas Melas had helped transport invaded Ottoman Macedonia on 28 March; the invasion failed quickly, but gave the Ottoman government the cause to declare war on Greece on 17 April [O.S. 5 April] 1897.[34]

Inspired by the feverishly nationalist climate of the time, Melas expected the war to lead to the capture of Thessaloniki,[33] while his diary reveals his enthusiasm at the outbreak of hostilities.[32] While his unit had been moved to the border, however, Melas remained at Larissa, where he learned of the collapse of the Greek front.[32] The rapid defeat and retreat of the Greek army, leading to the evacuation of Larissa, made him despair.[35][36] Unable to acknowledge the army's own inadequacies, Melas shifted blame for the on the politicians and the army leadership—though he excepted Crown Prince Constantine,[36] with whom the nationalist circles of the Ethniki Etaireia were in close contact.[17] Melas participated in the disastrous battles of Farsala (23 April) and Domokos (4 May). On 7 May, his regiment camped at Alamana; mentally and physically exhausted from the defeats and lack of sleep, Melas fell ill.[32] The regimental physician gave him leave from Lamia, from where Melas with a friend went to the hospital ship Thessalia at Agia Marina, where his wife Natalia was serving as a nurse.[37] The couple returned to Athens for a week, after which Melas requested and achieved his return to Lamia.[38] He stayed there until June, when he received news that his father lay ill and dying. Two days after his arrival in Athens, on 17 June, Michail Melas died.[39][40] At his father's coffin, Melas gave an oath to offer his life to his fatherland.[41] In 1898 Melas returned to Thessaly, taking part in the reoccupation of the region following the withdrawal of the Ottoman forces, and later as member of a commission, established by Queen Olga, which registered the material losses and destruction left by the war.[42]

In January 1899, Melas became a member of the executive board of the Ethniki Etaireia,[24] which however self-dissolved on 1 December 1900 after the general outcry for its role in precipitating the war of 1897, and a dispute with the government over the organization's treasure. Nevertheless, following a motion proposed by Melas and Nikolaos Politis (a diplomat and later foreign minister), the executive board resolved to "continue to meet regularly and deliberate on issues of national importance, and propose relevant solutions to the government of the day".[17] [32]

Involvement in the Macedonian Question

[edit]The Dragoumis network

[edit]

Despondent over the outcome of the 1897 war, Melas threw himself into the emerging Macedonian Question.[43] In Macedonia, Greek aspirations clashed with Bulgarian irredentism, which claimed territories considered "historical Greek lands";[44] for the Greeks, these territories were an integral part of the modern Greek national identity, which had been constructed largely by reference to Ancient Greece.[45] From the establishment of the Bulgarian Exarchate in 1870 onwards, the alarmed Greek political elites considered the Macedonian Question as the most important issue of Greek foreign policy.[46][47] One of the main points of contention were the local Slavic-speaking population,[48] who inhabited mostly the countryside of the Macedonian hinterland.[49][50] The contenders for the allegiance of the local Slavs engaged in an unprecedented educational and cultural propaganda contest, aiming to control the churches and communal schools,[48] institutions critical not only for the teaching of language, but also for the establishment of a national identity.[51] In 1893, the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) was founded by Macedono-Bulgarian revolutionaries, which officially campaigned for an autonomous Macedonia within the Ottoman Empire,[52][47][53] while at the same time preparing an armed uprising and taking steps to establish a parallel quasi-state in the Slavic-speaking countryside by means of armed guerrilla groups and terrorist strikes. By the early 1900s, IMRO had established a significant presence in the region.[54][55]

The Macedonian Question had especial resonance for the Dragoumis family, whose members, even the women, were actively engaged in it.[56][57] The family patriarch, Stefanos Dragoumis, himself of Macedonian descent, an ardent supporter of Greek irredentist aspirations and a former foreign minister, was one of the few who pushed for active involvement with Macedonian affairs in Athens against the mood of apathy and hopelessness that prevailed after the war of 1897.[58] The Dragoumis residence in Athens was widely considered the headquarters of Macedonian affairs. It was often visited by refugees and immigrants from Macedonia, to whom Melas used to gift photographs he had taken.[59] Around the Dragoumis family, on the initiative of Melas' brother-in-law, Ion Dragoumis, an organization was established for the defence of the Greeks in Macedonia. The project was enthusiastically taken up by young officers, especially those who, like Melas, had been members of the Ethniki Etaireia.[60] Officers serving in the Military Geographical Service helped transport weapons across the border, where they were taken over by men like the Metropolitan of Kastoria, Germanos Karavangelis,[61] the most aggressive representative of a group of similarly-aged bishops, recently installed by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople and supportive of Greek claims and aspirations. From early 1902 on, Karavangelis tried to erode IMRO support, approaching disillusioned IMRO members and forming them into armed groups. First among them was Kottas, a Slavic-speaker loyal to the Patriarchate[a] from the village of Roulia near Florina in western Macedonia.[63][64][65][66]

In November 1902, Ion Dragoumis was appointed vice-consul in Monastir.[67][66] From there he maintained a regular correspondence with Melas, requesting the dispatch of weapons and money, and the bribing of European newspapers.[67] In early 1903, Dragoumis founded his own organization at Monastir, named Amyna ('Defence'), to coordinate the Greek cause in western and central Macedonia.[64] In January 1903 Dragoumis wrote to Melas a letter announcing the imminent establishment, and the aims, of a society composed "of a few wealthy and good men".[17] After a request by Karavangelis, in May 1903 the circle around Dragoumis and Melas, with the assistance of second lieutenant Georgios Tsontos and funding from the French philhellene Louise Riencourt, sent eleven Cretan mercenaries, including Efthymios Kaoudis, to Kastoria. These armed men, legally Ottoman subjects, accompanied Karavangelis when he conducted services in villages loyal to the Bulgarian Exarchate, or attacked armed IMRO groups as well as rebel villagers after the outbreak of the Ilinden Uprising on 3 August [O.S. 20 July] 1903. In August, Karavangelis had to smuggle them with great difficulty back to Athens.[68][69][63]

For the Greek government, then led by Dimitrios Rallis, the Ilinden Uprising, revealed the extent of IMRO activity and the danger of Macedonia eventually falling under Bulgarian rule.[70][71] At the same time, however, Ion Dragoumis, increasingly frustrated by the slow pace of diplomacy and the cautious stance of the Greek foreign ministry, expressed doubts that Greece's parliamentary system could successfully pursue the irredentist national aspirations. In October he wrote to Melas to be ready to move militarily, either against the Bulgarians in Macedonia, or in a coup d'etat to be led by Timoleon Vassos, with the aim or replacing the government with one more ready to pursue an activist policy in Macedonia.[17][63][72] A few days later, however, taking into account the restrictions imposed by reality, he sent Melas different instructions.[72]

Reconnaissance tours

[edit]

In November 1903, the Sublime Gate accepted the Mürzsteg Agreement, concluded the previous month by Russia and Austria-Hungary. The third point of the agreement entailed the re-drafting of the administrative boundaries of Macedonia, following the regions' pacification, to better correspond to the distribution of its ethnicities.[73][74] For the Great Powers, the agreement aimed at stabilizing the status quo, but the Balkan peoples subject to the Ottoman Empire saw this as a guarantee of future assistance towards their respective irredentist aspirations.[75][76] The Christian Balkan states also took note of the third point. As within the Ottoman millet system, religious affiliation was used for ethnic categorization, adherence to one of the two churches, the Bulgarian Exarchate and the Patriarchate of Constantinople, was tantamount to their declaration as "Bulgarian" or "Greek" respectively.[75],[77] For that reason, Greece opposed the pacification of the region before the—often forcible—expansion of Exarchate influence over the past years could be reversed. The IMRO leadership, on the other hand, threw its support behind the Exarchate.[75][78] Action by the Ottoman authorities had recently managed to reduce the influence of both the Exarchate and IMRO. In winter 1903/4 IMRO's remaining armed groups focused their attention on forcing the return to the Exarchate of villages which had recently returned to Patriarchal allegiance, especially in the region of western Macedonia.[79][78] The alignment of any particular village with the Patriarchate or the Exarchate was fluid, depending on which of the two factions living in the settlelemt could count on the outside support of armed groups. In spring 1904, the contest for influence turned violent, with massacres taking place.[80][81]

In February 1904, a delegation arrived to Athens, composed of Kottas, Lakis Pyrzas from Florina, and Pavlos Kyrou, a Slavic-speaker from Zhelovo (modern Antartiko), to present the situation in Macedonia to the Greek government.[82][83] Melas met the first two at the Dragoumis residence.[84] Under the pressure of public opinion, the government of Georgios Theotokis turned its attention to the affairs of Macedonia, and sent a team of four army officers, headed by Alexandros Kontoulis, to assess the situation in western Macedonia,[82] as well as the prospects of an armed Greek intervention in the region.[85] For the other members of his team, Kontoulis selected Anastasios Papoulas, Georgios Kolokotronis, and his friend Melas,[82] over the objections of Foreign Minister Athos Romanos, who regarded Melas unsuitable as being too "impulsive".[86] Despite the disagreement of Natalia and the condescending attitude of the rest of her family, Melas himself was full of enthusiasm and awe at the prospect of going to Macedonia, a region which was foreign to him but would enable to him to fulfill his oath to his father and devote his life to a higher cause.[87] Melas was nevertheless distressed by the uncertainty of the mission, and the necessity of parting from his children, but was calmed by his wife.[88]

After selecting four companions, among them Kaoudis, the four officers set out along separate itineraries, meeting at Velemisti (modern Agiofyllo) on the Greek-Ottoman border in late February 1904, along with Kottas, Pyrzas, and Kyrou.[82][83] For reasons of secrecy, the officers were issued with passports under cover names; Melas bore the name "Zezas" (Ζέζας),[89] which in Arvanitic means "swarthy" or "black", and which had been given to Melas by the Arvanite Kontoulis.[90] The mission was delayed due to adverse weather, and the group did not cross the Aliakmon River until 22 March [O.S. 9 March] 1904. Via Siatista, the group went to the Saint Nicholas Monastery of Tsirilovo, near Korisos. Guided by a man sent by Karavengelis, they reached the village of Gavros on 28 March [O.S. 15 March]. On the next day, Melas and Kolokotronis donated money to the local school teacher, while in the afternoon Kottas, Kontoulis, and Melas held speeches to the locals in favour of siding with the Greek cause. After that, they moved on to Roulia (Kottas' home village), Ostima (modern Trigono), and Zhelovo (Kyrou's home village).[91]

Kottas, one of the last representatives of the klephtic tradition and the undisputed leader of the region's guerrillas, made a major impression on Melas, who treated him with respect and admiration, and began to view the situation in Macedonia through the Kottas' perspective.[92] At Zhelovo, Melas experienced first hand the effectiveness of the propaganda of IMRO representative Anastas Yankov among the local Slavic-speakers on the existence of a distinct Macedonian nation.[93] During their stay in the area, Melas and Kontoulis disagreed with Papoulas and Kolokotronis on the best course of action to defend Greek interests: while the latter supported the dispatch of armed groups from Greece, the former preferred raising armed groups from the local population,[94] a project espoused by Ion Dragoumis in his communications to Melas for the past year.[95] After Zhelovo, the group moved to Orovnik (modern Karyes), where the local priest, Stavros Tsamis, recognized Melas from a photograph of his, and declared that with his arrival, "great things will happen".[96][97] On the same day, the officers received a message from Dragoumis that the Ottoman authorities were alerted to Melas' presence, and that he would have to leave immediately for Greece. Melas visited Dragoumis at Monastir, where the latter persuaded him to obey the recall. A dejected Melas took the train for Thessaloniki, arriving in Athens on 29 March. The other officers returned to Athens five weeks later, on orders from the Foreign Ministry, while Kaoudis remained with Kottas.[98][99] While in Macedonia, the three officers had sent a report[b] which presented conditions as favourable for Greek armed activity, but Papoulas and Kolokotronis had also separately sent letters portraying their reception as poor, and the local population as unsuited for armed action.[100] Back in Athens, Melas and Koloktronis had a fierce disagreement on the issue, which led to a duel[c] on 28 May, which led to Kolokotronis being lightly wounded by Melas' gun.[102][103]

Melas assumed duties at the Army Academy, but after the arrival of two men from Kozani, who visited Stefanos Dragoumis in late June and reported readiness to take armed action, Melas was issued with a twenty-day leave to return to Macedonia.[104] This was much to the surprise and sorrow of his family, especially Natalia, who had to be consoled by Melas.[105] Accompanied by Pyrzas, Melas arrived at Kozani, which was populated almost entirely by Greeks, on 19 July under the guise of a cattle trader,[104] using the cover name "Pavlos Dedes" (Παύλος Δέδες).[106] Melas found out that the preparations for armed action were by far not as advanced as he had been led to believe, but met with the six-member local committee of Amyna at the city's episcopal residence. Along with the committee, Melas agreed on the establishment of seven armed groups of fifteen men each, to be active in the region of Kastoria and Vodena (Edessa), under the command of the klephts Alexandros Karalivanos and Sotirios Visvikis, as well as the monthly salary to be paid to the men. While Pyrzas was sent to examine the conditions for armed action at Vogatsiko and Kastoria, Melas sent a report to Stefanos Dragoumis asking for the dispatch of money to Kozani. He also visited Siatista, where he was enthused by the local committee he encountered. Melas also planned to visit Veroia, Naoussa, and Vodena, but as his term of leave was short, he had to return to Athens, arriving there on 3 August.[107]

During his stay at Kozani, Melas realized the necessity for sending armed men from Greece to Macedonia, and decided to take up armed action himself, following the recent example of his former Army Academy classmates Georgios Tsontos and Georgios Katechakis, who had been appointed heads of armed groups by the Macedonian Committee.[108] The latter was a semi-official irredentist organization founded in May 1904 by former members of the Ethniki Etaireia under the chairmanship of Dimitrios Kalapothakis (publisher of the newspaper Empros), with funding from the Greek government and aiming to prepare and send armed groups to Macedonia.[109][103] At about the same time as Melas was at Kozani, a mission sent by the Macedonian Committee determined the necessity of a coordinated Greek activity to avoid reprisals.[110] While Melas, just like Stefanos Dragoumis, never became members of the Committee, they closely cooperated with its members and used their networks.[67]

Macedonian Struggle

[edit]Route into Macedonia

[edit]

In June 1904 Kottas was denounced to the Ottoman authorities by his former collaborator, Pavlos Kyrou, at the instructions of Metropolitan Karavangelis. Kottas' arrest removed the main pillar of the Greek cause in the Koresteia region of western Macedonia,[111][112] so that in late July it was decided to send there armed groups from Greece.[113] Within the Macedonian Committee, a faction, led by Kalapothakis, favoured giving command to Kaoudis, while another, which aimed for closer relations with the Greek government, proposed Melas, acquainted with Prime Minister Theotokis.[114] Following the intervention of Theotokis,[5] on 14 August Melas was appointed head of all armed groups for the Monastir and Kastoria regions.[115] Kaoudis refused to join Melas' forces, as he had already promised Kalapothakis,[114] from whom he now received authorization for independent action.[116] On 18 August Kaoudis crossed the border at the head of an armed group, with Kyrou as his guide and co-captain.[117] On the same day, Melas left for Macedonia in secret, after saying farewell to his children; for this, his third mission, he was more calm than previously, but was certain that he would not return alive.[118] Melas was accompanied by three Cretans—including Ioannis Karavitis, who pressured Melas intensely for his inclusion[119]—and Pyrzas,[115] who joined up after failing to gather an armed group of his own.[120]

At Larisa, the group was joined by four Macedonians and the klepht Katsamakas with six men.[115] Melas was hosted by Second Lieutenant Charalambos Loufas, who asked for a photo of him. Melas agreed, and on 21 August was pictured by the photographer Gerasimos Dafnopoulos holding a Mauser carbine, with a Mauser C78 "zig-zag" revolver at his belt,[121] and wearing an embroidered black doulamas coat.[122] Melas sent the first copy of the photo to his wife, "under the condition that it does not see the light of day" but remain as a souvenir for her and his children, should he be killed,[121] considering that it would be a torture, should he return without having achieved anything, to see "[his] face dressed up like that".[122] The group departed Larisa on the next day[123] and arrived at the Meritsa Monastery on the 27th, where they were reluctantly hosted by the abbot.[115]

On the night of 27/28 August, Melas, under the nom de guerre "Kapetan Mikis Zezas" (καπετάν Μίκης Ζέζας), which reflected both his son's and his father's names, and accompanied by about 35 armed men, crossed the Greek-Ottoman border near Ostrovo (modern Agnantia).[115][124][125][126] As with his two prior forays into Macedonia, Melas retained some aspects of his daily family life; he kept his watch on Greek time, and pondered what his family would be doing during the day.[127] His group included local klephts and Cretans of a similar background, who were familiar with moving and fighting as irregular forces. After crossing the border, Melas himself tried to adopt the klephtic tradition, no longer wearing his regular army uniform,[128] but replacing it with the doulamas, which helped him gain the respect of his men.[122] Although not very practical, especially during poor weather conditions, the traditional klephtic dress helped Melas feel more comfortable in his role. Like many of his fellow "Macedonian fighters" he found that it helped to raise morale among his men.[129]

On 30 August the brigand Thanasis Vagias, whom Melas had hired as a guide, defected and betrayed the presence of Melas and his men to the Ottomans.[130] For over a week thereafter, Melas and his men remained constantly on the move in the Samarina area, marching by night, often under rain, an ordeal for Melas, who was unused to such exertions.[131][132] The local population proved suspicious and remained aloof of the group.[133] Finally, on 5 September Melas and his men reached the village of Zansko (modern Zoni), where a supporter sheltered and supplied them.[134] Two days later they crossed the Aliakmon and made for the Greek-speaking, Patriarchist village of Kostaratsi, where they stayed for three days listening to requests for assistance from other villages of the region. Via Vogatsiko and the Monastery of St. Nicholas of Tsirilovo, the major staging place for Greek armed groups in the region, they arrived on 13 September to the Albanian-speaking Patriarchist village of Lechovo. There they met the local klepht Zisis Dimoulios, who with Ottoman sanction maintained an armed body of nine men, and was working for the Patriarchist cause.[131][d] There Melas and Pyrzas reluctantly discussed the necessity of reprisals for the murder of the priest of the Slavic-speaking village of Strebeno (modern Asprogeia) by Bulgarian-aligned komitadjis in November 1901.[135][136] Melas' anguish when confronted with the necessity of killing people is evident in his own letters home: "I will never forget how much I suffered today afternoon. I constantly questioned myself whether I had the right to arrest anyone, no matter his villainy and pull him away from his family and kill him! And I constantly replied no, no! [...] But I had no other support but my love for my fatherland and my nation. Truth be told, I must love them both dearly, because, although I suffer, although I cry, I will let what has been decided to occur."[137]

For Melas, as for the other Greek officers who went from the free Greek kingdom to Macedonia, the refusal of Slavic-speaking villagers to recognize the headship of the Exarchate instead of the Patriarchate was proof of their Greek "consciousness". Melas considered the Slavic-speaking Macedonian peasants equally Grek to the Greek-speaking Cretans that accompanied him, believing that they had simply forgotten their original language as the result of foreign rule, migrations, and the lack of a Greek education.[138] He called them simply "Macedonians", as inhabitants of Macedonia, and their language "Macedonian". To Melas, like other Greek army officers active in Macedonia, they were not different to the Vlach or Albanian-speaking locals, who were also regarded as Greek by virtue of their adherence to the Patriarchate of Constantinople.[139] Realizing the difficulty of aligning the peasantry with modern notions of nationalism, Melas explained that his struggle was based on religion, which was being offended by the Bulgarian actions. He himself chose for his seal, which he requested from Karavangelis, to feature a cross, as well as—inspired by the seal of the Ethniki Etaireia—the phrase "by this sign conquer" (ἐν τούτῳ νίκα), both of which were symbols known and understood by the peasants he tried to recruit into his cause.[140][141]

Armed action

[edit]On 15 September, Melas carried out his first operation at Strebeno, where there were two Exarchists sought by the Greeks, whom he had identified with the assistance of isis Dimoulios. Melas' men entered the village during the night and arrested the men, but after entreaties by the locals, agreed not to execute them, if they went to the Greek metropolitan bishop of Kastoria and declared their submission;[142] to ensure they would do so, he had them swear with their hands on a Bible.[143] At the same time, he gave the village elders ten days to also return to the allegiance of the Patriarchate, by going to the Metropolitan of Kastoria and asking for the dispatch of a teacher and a priest.[144] Melas also distributed money to the relatives of victims of Exarchist violence, disbanded the local IMRO committee, and replaced it with a "defence committee" composed of Patriarchists.[145] Melas' mild treatment of the Exarchists angered the local Patriarchists, who were eager to seek retribution for the violence suffered at the hands of pro-Bulgarian armed bands during the previous years.[143] Doubts spread among Melas' own men; according to his own testimony, Karavitis began to doubt whether his chief had the physical and mental hardness required for the task. However, despite the doubts of his men, Melas continued to enjoy their respect for his moral clarity and civility.[146]

On 17 September, Melas tried to organize an attack on the Exarchist stronghold of Aetozi (modern Aetos), but the refusal of Dimoulios to cooperate thwarted his plans.[147] Without someone who knew the region and without the ability to track the furtive movements of Exarchist bands, Melas was forced to turn to reprisals against individuals. On the same day he decided to move to Prekopana (modern Perikopi),[148] where his men surrounded the local population during a funeral service, and took prisoner the village's Exarchist priest and teacher;[149] the priest, Nikola, had murdered his Patriarchist predecessor in July 1903.[150] Driven by fear, the local villagers and village elders renounced the Exarchate, with Melas demanding, as in Strebeno, that they submit to the Metropolitan of Kastoria and ask for a new priest and teacher; if they broke their oath, he threatened to return and punish them.[151] The execution of the two men, which took place a short distance from the village,[152] shocked Melas by the difference between the "beautiful and noble work" that he had undertaken, and the "hard necessities" demanded for its realization.[153]

Melas then moved to Belkamen (modern Drosopigi), a village inhabited by Albanians and Vlachs. Melas held a speech, organized a "defence committee", and closed the local Romanian school.[154] Next, Melas and his men secretly entered the Slavic-speaking village Neret (modern Polypotamo), aiming to arrest five IMRO komitadjis. However, they failed to make contact with the local Patriarchists, and had to abort their plans when they realized that a significant number of Ottoman troops was present in the village.[155] During the subsequent disorganized flight under fire, Filippos Kapetanopoulos, a member of the Monastir Amyna group who had joined Melas' band at Belkamen, was mortally wounded,[156] highlighting Melas' lack of experience in guerrilla warfare,[157] Melas covered him with the latter's cape, without checking that a letter by Kapetanopoulos to the Greek consul in Monastir, Dimitrios Kallergis, was in its pocket. When the Ottomans discovered the body and the letter, the Ottoman government lodged a formal protest with the Greek government, resulting in Kallergis' recall.[158] Melas wrote a draft report for the local Ottoman governor (kaymakam), which was never finished or delivered, where he tried to justify his band's presence in the area as having as their sole aim "the punishment of Bulgarian murderers and the protection of our brothers from their hordes".[5][159] Indeed, the activity of Melas' band was disapproved of by the Ottoman politicians, but not the local military authorities, who did not take any measures to neutralize it.[160]

From Neret, Melas and his men moved to Lechovo and thence to Negovan (modern Flambouro), a majority Patriarchist village with mixed Albanian and Vlach population, where the band stayed for several days due to the incessant rainfall.[161] On 30 September, the village elders of the Vlach village of Neveska (modern Nymfaio) came to Negovan, bringing food and clothing for the band.[162] Lechovo, where Dimoulios resided, and Negovan became bases of operation for Melas. With money sent by the Macedonian Committee he paid the wages of the chieftain Kole Pina, who had worked for Karavangelis, setting Neveska as the common base for Dimoulios and Kole. Macedonian Committee funds also paid for five-member armed "defence committees" at Neveska and other villages, whose job was to ensure the supply of the guerrilla bands, the security of their villages, and propaganda activity in their area, as well as the recruitment of messengers and spies.[163]

At the same time, Kaoudis and Kyrou were active with their own armed band in the Koresteia region, forcing many komitadjis to abandon their villages. On 1 October [O.S. 18 September] 1904, this band launched a surprise attack on the komitadji band of Mitre the Vlach at Ostima (modern Trigono). After a fierce battle that lasted several hours, Mitre managed to escape, but lost about twenty men.[164] Melas received news of the battle at Lechovo. He had previously sent messages to Kaoudis ordering him to join with his own band, but had received no response, which he judged a deliberate refusal from Kaoudis; in reality, the latter, who also favoured joint action, had never received them.[165] The two leaders managed to communicate on 25 September, but the lack of reliable means of communication meant that their three attempts to meet face to face failed.[166]

Disappointed by the poor weather conditions, the encounters with the Ottoman army, the ability of his enemies to evade him, the reluctance of the local population to aid him, and the lack of more men and money from the Macedonian Committee,[167] Melas considered returning to Athens after leaving small detachments in the local villages, and coming back to Macedonia in March 1905 with a new armed band. However, on 9 October he unexpectedly received reinforcements from Greece,[5] with the arrival of Karalivanos and forty men at Negovan. This meant that Melas now had over 70 men under his command, divided into four groups under Karalivanos, Ioannis Fistopoulos, Pyrzas, and Ioannis Poulakas.[162] In his last letter, sent to his sister in law, Efi Kallergi—a daughter of Stefanos Dragoumis who was married to the cavalry officer Ioannis Kallergis, with whom Melas had an affair during the last months of his life—he described his resolution to remain in Macedonia.[168][169] Having organized the defence of the villages in the Kastoria area, he intended to leave some 50 men behind to control the area and with the remainder move via Zhelovo and Pisoderi to the area of Magarevo and Monastir, expel the komitadji groups from the local villages, and organize their defence before winter.[168] In a report to the Macedonian Committee Melas wrote that after Monastir he intended to move towards Vodena and Veroia, extending his activity over the entire region of which he had been placed in charge.[170] Two days later, with 60 men, he attacked proscribed IMRO members and Neret,[5] after a warning that three komitadji groups were hiding there, received by the son of the village's former priest, who had been murdered by IMRO.[171] The operation failed, and during its retreat, the Greek band was attacked by the komitadjis and fled in disorder.[5]

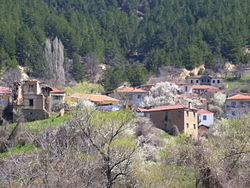

Death

[edit]After the failed raid on Neret, Melas was left with a force half its original size.[5] They spent the night under rainfall at Vitsi,[172] and moved to Statista (modern Melas), where they met Dine or Dina Stergiou, a 24-year-old former komitadji and member of Mitre the Vlach's band, who had abandoned it due to personal rivalries. Karavangelis had recommended him to Kaoudis and Kyrou, but though they allowed him to join their band, they were not convinced of the sincerity of his change in allegiance to the Greek cause.[172][173] Stergiou invited Melas to spend the night in Statista,[172] a Slavic-speaking village with a mixed Patriarchist and Exarchist population,[174][175] but with an organized pro-Bulgarian faction.[172] Melas disregarded a recommendation from Pyrzas to not enter the village, as Ottoman troops often passed through,[174] and sent a message to Kyrou and Kaoudis to meet on 14 October at dawn near Statista.[174][172] Kaoudis, in the belief that Melas had come to reinforce him, began preparing to go to Statista, but Kyrou opposed it; he was both loath to leave his native Zhelovo, which was under threat from Exarchist bands, as well as having a poor relationship with Melas, who had accused him of betraying Kotas. In the end, only two men were sent to the meeting, to bring Melas' men to Zhelovo.[176]

At Statista, Melas' band was hosted by Stergiou and the village elders.[174] Stergiou helped divide the men among five houses, and promised to lead them to the meeting place with Kaoudis and Kyrou on 14 October.[172][173] During the evening of 13 October, news arrived that an Ottoman detachment had left Konomladi (modern Makrochori), but Melas was not concerned. He knew that the Ottomans did not intentionally attack Greek bands, as they too helped them fight the komitadjis. However, the detachment was set in motion by a forged letter by Mitre the Vlach. The letter, written in Greek, purported that Mitre himself was at Statista; as the komitadji leader had a bounty placed on his head by the Ottomans, Mitre was certain that the Ottoman captain would head to Statista to capture him, and hit Melas and his men instead.[174][177] The village was soon surrounded by a few dozen Ottoman soldiers, and isolated combats broke out. At dawn on the next day, Melas was dead, under unclear circumstances.[178]

There are several versions about Melas' death.[179] The Ottoman detachment discovered one of the Greeks' hideouts, and a firefight broke out.[179] The Ottomans also encircled the house in which were Melas, Pyrzas, Stergiou,[174] Petros Hatzitasis,[180] and a Cretan named Stratinakis, and which was explicitly mentioned in Mitre's letter.[174] Most accounts of Melas' men dispute that there was a fight, and it is doubtful whether Melas and the others who were with him. All versions agree that at some point during the night, Melas tried to escape and was mortally wounded, but differ on the source of the fatal shot: some claim it came from the Ottomans, others from the accidental firing of Pyrzas' rifle.[178][179] After his wounding, Melas asked Pyrzas to hand over his cross to his wife, his rifle to his son, and a gold Byzantine coin pendant he wore as talisman to Efi Kallergi.[169][181] Witness accounts also disagree on whether Melas died of his wound, committed suicide, asked Stergiou to kill him, or whether the latter finished him off on his own.[182][179] Melas was apparently the only casualty on the Greek side. Apart from seven men from the hideout engaged by the Ottomans, who were forced to surrender when the house was set on fire, all of the band's men escaped. The captives were convicted in 1905 to five years' imprisonment for the forming of a gang.[179] Melas' companions left his corpse in the house's barn and made for Zhelovo. The body was retrieved by local villagers and buried in Statista, likely on the same night.[183]

Aftermath

[edit]

On the morning of the next day, 14 October, the four men who were with Melas reached Zhelovo. There they met Kaoudis and Kyrou, and informed them of their leader's death.[183][179] On the same day, Stergiou was sent to Statista for news; he returned after two days, reporting that there was the danger that Melas' head might be cut off as a prize. On the evening of 17 October, the entire band left for Belkamen, apart from Kyrou, who remained at Zhelovo, and Stergiou, who was sent back to Statista with five Ottoman liras to retrieve Melas' corpse. On the next morning, Stergiou appeared at Zhelovo holding Melas' head. To Kyrou and an official of the Greek consulate at Monastir, who had just arrived, Stergiou claimed that as he was exhuming the corpse, Ottoman troops entered the village, forcing him to hastily cut the head and leave.[183]

Melas' head was buried at the chapel of the Churst of St. Paraskevi at Pisoderi,[184][185] by the priest Stavros Tsamis.[186] At Statista, the Ottomans after a search discovered the headless corpse of Melas, and brought it to Kastoria.[187] According to the memoirs of Germanos Karavangelis, the local kaymakam searched the corpse and discovered letters addressed to "Mister Tzetzas" (Melas' nom de guerre), which allowed Karavangelis to identify the corpse. The Metropolitan insisted that the corpse be handed over to him to be buried as a Greek, while the kaymakam initially insisted to hand it over to a Bulgarian priest. Karavangelis mobilized the local Greek youth, as well as the local Turkish beys, threatening with the outbreak of riots that would harm the peaceful coexistence of Greeks and Turks. Under the pressure of the beys, the kaymakam handed over the corpse, which was buried in the courtyard of the Byzantine Church of the Archangel of the Metropolis.[184][185]

In 1907, Stefanos Dragoumis asked Karavangelis to permit the attendance of Natalia Mela for an exhumation of her husband's corpse, as well as the handover of Melas' head. Karavangelis arranged for the head to be brought from Pisoderi to Kastoria, where Natalia confirmed, through the presence of three gold teeth, that it was indeed her husband's head. Karavangelis then reburied the entire corpse, with the head, under the altar of the metropolitan cathedral.[183][188] Melas' remains were finally moved in July 1950 to a tomb inside the Archangel chapel.[189]

- Funerary memorials

-

Melas' original tomb at Kastoria in 1904

-

Cenotaph at Melas' original burial site in Statista (now Melas) in 2007

-

Memorial at Melas' initial tomb outside the Archangel church, Kastoria, in 2008

-

Tomb of Melas inside the Archangel church, Kastoria, in 2021

Pyrzas sent a report of Melas' death to the Monastir consulate only on 16 October, which relayed the news to Athens on the next day, but the telegram did not arrive at the Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs until the 18th. Melas' family and the Dragoumis family were informed first, and the news was published in the press the next day.p[187][190] The prevailing narrative was that Melas was willingly killed, defying danger on account of his patriotism;[191] the Athenian press reported incorrectly that Melas was shot after he and his band had broken through the Ottoman encirclement.[179] The circulation of many different rumours, along with the effort to hide embarrassing details,[192] such as that Melas' men did not expect to be attacked by the Ottoman troops, who in turn did so thinking they were a Bulgarian group, something which was kept hidden from the Greek public opinion,[179] helped to create an aura of mystery around the circumstances of Melas' death.[192]

Melas was succeeded in his leadership of the Greek bands in western Macedonia in mid-November by another army officer, Georgios Tsontos, who became known as "Kapetan Vardas". It was he who scored the first significant successes against IMRO, restored Greek prestige among the locals, and emerged as the most important Greek commander of the Macedonian Struggle.[193] In 1907, Tsontos received information that Stergiou, fearing for his life as he had killed Melas, had emigrated to the United States in 1905.[187][173] Three years later, a Greek agent was still writing to Stefanos Dragoumis that he was searching for Stergiou, determined to give him the "bitter death" he deserved as a traitor responsible for Melas' death.[173]

Legacy

[edit]Λίγες μέρες μετά τον θάνατο του Μελά, δημοσιεύθηκαν στις εφημερίδες ποιήματα γνωστών και άσημων ποιητών για τον Μελά,[194] ενώ η Ακρόπολις δημοσίευσε σχετικό ποίημα του Κωστή Παλαμά που εντάχθηκε στη σχολική ύλη.[195][196] Στις εκκλησίες της Ελλάδας τελέστηκαν μνημόσυνα για τον Μελά, ενώ στα σχολεία εκφωνήθηκε μια ομιλία συνταγμένη από την «Επίκουρο των Μακεδόνων Επιτροπή» που τον εξυμνούσε ως γενναίο «Βουλγαροκτόνο», απόστολο της Μεγάλης Ιδέας και φιλόπατρι θυσιασθέντα υπέρ της ελευθερίας, αντάξιο των μεγάλων ανδρών της αρχαίας Ελλάδας.[191] Πάνω από 100.000 άνθρωποι συμμετείχαν στο οργανωμένο από μια δημοσιογραφική ένωση μνημόσυνό του στην Αθήνα, προσδίδοντάς του χαρακτήρα διαδήλωσης.[197] Ο θάνατός του Μελά αποτέλεσε επίσης θέμα θεατρικών έργων,[195][198] ποιημάτων Μακεδόνων ποιητών[199] και δημοτικών τραγουδιών από όλες τις περιοχές της Ελλάδας.[200] Σε συνθήκες μυστικότητας ο Καστοριανός φωτογράφος Λεωνίδας Παπάζογλου φωτογράφησε τον Νοέμβριο του 1904 τον στεφανωμένο τάφο του Μελά και οι παραχθείσες εικόνες διοχετεύθηκαν από τον αδερφό του Μελά, Κωνσταντίνο, στον ελληνικό τύπο και κατόπιν αναπαρήχθησαν μαζικά ως καρτ ποστάλ, όπως συνέβη και με διάφορες απεικονίσεις του Μελά.[201][202]

- Depictions in art

-

Ο Μελάς σε πορτραίτο του Ιακωβίδη

-

Ο Μελάς σε πορτραίτο του Ιακωβίδη, εμπνευσμένο από τη φωτογραφία της 21 Αυγούστου 1904.

-

Ο Μελάς σε έργο του Θεόφιλου.

Η φωτογραφία του Μελά της 21ης Αυγούστου με αντάρτικη περιβολή αποτέλεσε την έμπνευση για πορτρέτο που αναπαρήχθη στο πρωτοσέλιδο της εφημερίδας Άστυ και ακολούθως σε επιστολικά δελτάρια,[195] αλλά και πρότυπο μίμησης για τις φωτογραφίες κατοπινών Μακεδονομάχων.[203] Την ίδια χρονιά ο Γεώργιος Ιακωβίδης φιλοτέχνησε κατά παραγγελία της Λουίζας Ριανκούρ ένα πορτρέτο του Μελά με βάση τη φωτογραφία του Μελά στη Λάρισα,[204][205] ενώ με την ενδυμασία του Μακεδονομάχου ο Μελάς εικονίστηκε ως εθνομάρτυρας και σύμβολο του Μακεδονικού Αγώνα και από τον ζωγράφο Θεόφιλο.[206] Κατά τον ιστορικό Βασίλη Γούναρη, η ιστορία και η σημασία της φωτογραφίας αυτής, που μαζί με τον πίνακα του Ιακωβίδη έγιναν το γνωστότερο και μακροβιότερο σύμβολο του Μακεδονικού Αγώνα, «είναι το καλύτερο παράδειγμα της απόστασης που χωρίζει τη συμβολική, σχεδόν μυθική, σημασία του Μακεδονικού Αγώνα από την ιστορία του».[204]

Αν και ο Μελάς ήταν ιδανικός για το έργο της προώθησης του ελληνισμού στη Μακεδονία, τα άμεσα αποτελέσματα της δράσης του ως οπλαρχηγού ήταν πενιχρά.[208] Ο θάνατος, όμως, ενός γνώριμου στους πολιτικούς και δημοσιογραφικούς κύκλους μεγαλοαστού αξιωματικού κατά τον τύπο του παραδοσιακού «παλληκαριού», του «κλέφτη»-ελευθερωτή, ιδιότητα με την οποία ο Μελάς συνειδητά επιδίωξε να ταυτιστεί κατά την έξοδό του στη Μακεδονία το φθινόπωρο του 1904, σε μια περίοδο κατά την οποία ο τακτικός στρατός θεωρούνταν άνευ αξίας, ενώ οι άτακτοι πολεμιστές ο αληθινός «στρατός του έθνους», ανέδειξε τον Μελά ως μέλος του ελληνικού εθνικού πανθέου, συγκλόνισε την κοινή γνώμη της εποχής, εξώθησε πολλούς εθελοντές να ακολουθήσουν το παράδειγμά του και κατέστησε αδύνατο για τις ελληνικές κυβερνήσεις να παραβλέψουν την υπόθεση της Μακεδονίας.[209][179] Ήδη πριν την ένταξη της Μακεδονίας στο ελληνικό κράτος, ο Μελάς είχε γίνει εθνικός ήρωας και σύμβολο του Μακεδονικού Αγώνα.[210]

Την περίοδο του Μεσοπολέμου, όταν η εν εξελίξει προσπάθεια αφομοίωσης των σλαβόφωνων στο ελληνικό έθνος και η συνέχιση ύπαρξης διαμαχών μεταξύ των πολιτικά ενεργών Μακεδονομάχων οδηγούσε στον αποκλεισμό του Μακεδονικού Αγώνα από τον επίσημο δημόσιο λόγο, η απότιση φόρου τιμής στον Μελά λειτούργησε ως υποκατάστατο της δημόσιας μνημόνευσης του Μακεδονικού Αγώνα.[210][212] Επί μακεδονικού εδάφους, το 1920 τοποθετήθηκε στο κενοτάφιό του Μελά στην Καστοριά, μετά από παραγγελία της Ναταλίας και με συγχρηματοδότηση του εκεί δήμου, μία προτομή του επί ενεπίγραφης στήλης που τον παρουσίαζε ως «πρωτομάρτυρα της μακεδονικής ελευθερίας», κατ' αναλογίαν με «εθνομάρτυρες», όπως ο Ρήγας και ο Γρηγόριος Ε΄.[213] Το όνομα του Μελά δόθηκε το 1927 στη Στάτιστα, το χωριό όπου σκοτώθηκε, που ονομάζεται σήμερα Μελάς,[214] και σε μία εθνικόφρονα και, υπό την επίδραση της θέσης του ΚΚΕ για ανεξάρτητη Μακεδονία, αντικομμουνιστική «Εθνική Οργάνωση» ντόπιων κυρίως Μακεδονομάχων που ιδρύθηκε τον ίδιο χρόνο, γρήγορα εξαπλώθηκε σε πόλεις και κωμοπόλεις της Μακεδονίας και στόχευε στην ικανοποίηση μέσω πελατειακών δικτύων αιτημάτων υλικής αποκατάστασης των μελών της.[215] Το 1931 ένα στρατόπεδο στο δυτικό τμήμα της Θεσσαλονίκης μετονομάστηκε προς τιμήν του σε «στρατόπεδο Παύλου Μελά».[216] Το 1934 ανεγέρθηκε στον πρώτο τάφο του Μελά, στη Στάτιστα, ένα μνημείο, που τον Οκτώβριο του ίδιου έτους καταστράφηκε από αγνώστους (ο βενιζελικός γερουσιαστής Λεωνίδας Ιασωνίδης καταλόγισε την ευθύνη σε «βουλγαρίζοντας βουλγαροφώνους» της περιοχής), αλλά ανεγέρθηκε εκ νέου από την τοπική κοινότητα.[217][218] Το δεύτερο μισό της δεκαετίας του 1940 η στοχευμένη παρουσίαση των κομμουνιστών ως "Βουλγάρων" και η θεώρηση του εμφυλίου πολέμου ως επανάληψης της ελληνοβουλγαρικής διένεξης των αρχών του αιώνα είχε ως αποτέλεσμα την επιστράτευση στην εθνικόφρονα ρητορική της εποχής των συμβολικών μορφών του Δραγούμη και του Μελά, το όνομα του οποίου δόθηκε σε μία σειρά από τοπόσημα και διοργανώσεις.[219]

Το 1907 ο κουνιάδος του Μελά, Ίων Dragoumis, δημοσίευσε με το ψευδώνυμο «Ίδας» το πρώτο αφηγηματικό κείμενο για τον Μελά, το βιβλίο Μαρτύρων και ηρώων αίμα,[220] στο οποίο παρουσίαζε τον Μελά ως το μοναδικό ως τον θάνατό του υποστηρικτή της ελληνικής υπόθεσης στη Μακεδονία και τον προέβαλλε ως «παλληκάρι» άξιο μίμησης και θαυμασμού από τους νέους της εποχής,[221] ενώ η Πηνελόπη Δέλτα, ακροάτρια των αναμνήσεων του Δραγούμη, έκανε τον θάνατο του Μελά κεντρικό συμβάν του μυθιστορήματος Ο Μάγκας.[222] Το 1926 δημοσιεύθηκε ανώνυμα στην Αλεξάνδρεια και το 1963 επώνυμα στην Αθήνα μία βιογραφία του Μελά γραμμένη από τη σύζυγό του, Ναταλία Δραγούμη, συνοδευόμενη από την επιστολογραφία του και εικονογραφημένη από τον Φώτη Κόντογλου.[5][223] Η Ναταλία επενέβη στη γλώσσα του σημειωματαρίου του Μελά και των επιστολών του, ώστε να είναι περισσότερο κατάλληλη για δημοσίευση, και λογόκρινε αναφορές που υπήρχαν σε προσωπικές στιγμές του Μελά με την ίδια, τα παιδιά του ή την Έφη Καλλέργη, καθώς και σε πρακτικές που μπορούσαν να απομυθοποιήσουν τον Μακεδονικό Αγώνα στην κοινή γνώμη, όπως την παροχή χρημάτων σε εμπλεκόμενους στον Αγώνα ή διηγήσεις του Μελά για την ανευθυνότητα πολλών από αυτούς.[224] Ο Μελάς ενέπνευσε επίσης τη μυθοπλασία της μεταπολεμικής πεζογραφίας, από τα διηγήματα του Γεώργιου Μόδη ως και, ενενήντα χρόνια μετά τον θάνατό του, το μυθιστόρημα Η κεφαλή του Νίκου Μπακόλα.[225] Την περίοδο της στρατιωτικής δικτατορίας γυρίστηκε η ταινία Παύλος Μελάς, ένα ηρωικό πολεμικό μελόδραμα αμφισβητούμενης ιστορικής ακρίβειας, που είχε ως θέμα την προσωπικότητα και τη δράση του Μελά,[226][227][228][229] σε σκηνοθεσία Φίλιππου Φυλακτού με τον Λάκη Κομνηνό στον πρωταγωνιστικό ρόλο.[230] Η ταινία αποτελούσε παραγγελία της στρατιωτικής κυβέρνησης και παραγωγή του Αρχηγείου Στρατού (που συγκάλυψε τον ρόλο του)[231][232][227] και αποσκοπούσε στην προπαγάνδιση της θέσης της συνεχούς και αποκλειστικής ελληνικότητας της Μακεδονίας. Προβλήθηκε για σύντομο χρονικό διάστημα το 1974,[228] υποχρεωτικά στο σύνολο των μαθητών,[227] προκαλώντας την αντίδραση της Βουλγαρίας[232] και αποσπώντας αρνητικές κριτικές στον τύπο της εποχής για την καλλιτεχνική της αξία, αλλά θετικές για το ιδεολογικό της περιεχόμενο.[228]

Το σπίτι όπου βρήκε τον θάνατο ο Μελάς μετατράπηκε σε μουσείο το 1963 και έκτοτε κάθε χρόνο τελείται στον Μελά μνημόσυνο, το οποίο παρακολουθεί πολύς κόσμος και αξιωματούχοι.[233][183] Με βασιλικό διάταγμα του 1969 η πρώτη Κυριακή μετά την επέτειο θανάτου του Μελά, 13 Οκτωβρίου, έχει οριστεί ως «Ημέρα του Μακεδονικού Αγώνος», δημόσια εορτή για τη Μακεδονία και τη Θράκη.[234] Την περίοδο του Μακεδονικού, στις αρχές της δεκαετίας του '90, μετά την ανεξαρτητοποίηση της Γιουγκοσλαβικής Μακεδονίας, σημειώθηκε αναζωπύρωση του ενδιαφέροντος για τον Μελά και η ενενηκοστή επέτειος του θανάτου του κηρύχθηκε σχολική αργία.[235] Ο Μελάς συχνά παρουσιάζεται, ως συνδεόμενος με τον αγώνα υπεράσπισης της ελληνικότητας της Μακεδονίας, μαζί με τον Μέγα Αλέξανδρο, όπως τους απεικόνισε και ο Νίκος Εγγονόπουλος στον πίνακα «Οι δύο Μακεδόνες».[236] Πλήθος από ανδριάντες έχουν αναγερθεί σε πλατείες πόλεων, οδοί και πλατείες ανά την Ελλάδα φέρουν το όνομά του,[237] ενώ πολλά προσωπικά του αντικείμενα εκτίθενται τώρα στο Μουσείο Μακεδονικού Αγώνα Θεσσαλονίκης.[238] Στη Θεσσαλονίκη, με το πρόγραμμα «Καλλικράτης» οι δήμοι Σταυρούπολης, Πολίχνης και Ευκαρπίας ενώθηκαν το 2010 σε έναν δήμο, στα όρια του οποίου ανήκει το στρατόπεδο «Παύλου Μελά» (που έπαψε να λειτουργεί το 2006) και ο οποίος έχει την ονομασία Παύλος Μελάς.[239][240] Γνωρίζοντας ευρεία απήχηση στην ελληνική κοινωνία, τον 21ο αιώνα η ανάδειξη της μορφής του Μελά ως ενσάρκωσης συντηρητικών αξιών και ηρωικού προτύπου εθνικής αυτοθυσίας έγινε σημείο σύγκλισης πτερύγων της δεξιάς.[169] Ως ρήση του Μελά παρουσιάζεται από Έλληνες ακροδεξιούς μία δήλωση ενός βασιλόφρονα Γάλλου στρατηγού της εποχής της Γαλλικής Επανάστασης για ανυποχώρητη μάχη μέχρις εσχάτων,[241] ενώ η Χρυσή Αυγή έχει εντάξει τον Μελά σε ένα πάνθεο αναγνωριζόμενων από το κράτος και την εθνική ιστοριογραφία ηρώων,[242] προς τιμήν των οποίων οργανώνει περιστασιακά εκδηλώσεις μνήμης.[243] Στα συλλαλητήρια εναντίον της συμφωνίας των Πρεσπών ακούστηκαν συνθήματα για τον Μελά,[244] ενώ αναφορές στον Μελά έγιναν και στη σχετική κοινοβουλευτική συζήτηση.[5] Το σπίτι του Μελά στην Κηφισιά εγκαταλείφθηκε, αλλά το 2009 αναγνωρίστηκε ως μνημείο,[245] δωρήθηκε στο Υπουργείο Άμυνας και το 2020 αποκαταστάθηκε.[246]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Kottas was the first of "many leaders who fought and fell in the field defending the Greek cause, though they did not speak but Bulgarian".[62]

- ^ The report, dated 16 April 1904, is reproduced in Dragoumis 2000, pp. 636–647

- ^ Duelling had become a popular means of defending their honour for Greek officers, especially after the humiliating defeat in the 1897 war, which was perceived as having collectively disgraced them[101]

- ^ At his home Dimoulios openly displayed photographs of Crown Princess (and later Queen) Sophia and Stefanos Dragoumis.[96]

References

[edit]- ^ Note: Greece officially adopted the Gregorian calendar on 16 February 1923 (which became 1 March). All dates prior to that, unless specifically denoted, are Old Style.

- ^ Mela 1992, pp. 17, 20.

- ^ a b c d Dakin 1966, p. 140.

- ^ Delis, Apostolos (2007). "Οικογένεια Μελά". Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World: Black Sea (in Greek). Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Cite error: The named reference

Kostopoulos20181014was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c Karambati & Nikoltsios 2014, p. 19.

- ^ Koliopoulos & Veremis 2002, p. 231.

- ^ a b Dakin 1966, pp. 140–141.

- ^ a b Karambati & Nikoltsios 2014, p. 39.

- ^ a b Mela 1992, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Mela 1992, pp. 56, 176.

- ^ Grigoratou & Melpidou 2015, p. 9.

- ^ Karambati 2005, pp. 28–31.

- ^ Liontis 2004, p. 10.

- ^ Karambati & Nikoltsios 2014, p. 13.

- ^ Gianoulopoulos 2003, pp. 16, 50.

- ^ a b c d e Ios 2013b.

- ^ Gianoulopoulos 2003, pp. 33–34.

- ^ a b c d e f Pikros 1977, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Vergopoulos 1977, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Pikros 1977, pp. 93–96.

- ^ a b Koliopoulos 1987, p. 17.

- ^ Gianoulopoulos 2003, p. 50, note 4.

- ^ a b Gianoulopoulos 2003, p. 50.

- ^ Hellenic Army History Directorate 1993, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Pikros 1977, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Hellenic Army History Directorate 1993, pp. 33–35.

- ^ Mela 1992, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Maroniti 2003, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Hellenic Army History Directorate 1993, pp. 22–38.

- ^ Mela 1992, pp. 66–69.

- ^ a b c d e Kostopoulos 2018b.

- ^ a b Karambati & Nikoltsios 2014, p. 53.

- ^ Pikros 1977, p. 127.

- ^ Mela 1992, pp. 104–105.

- ^ a b Karambati & Nikoltsios 2014, p. 55.

- ^ Mela 1992, pp. 121–123.

- ^ Mela 1992, p. 127.

- ^ Mela 1992, pp. 128–129.

- ^ "ΜΙΧΑΗΛ ΜΕΛΑΣ. Ο ΘΑΝΑΤΟΣ ΤΟΥ". Empros. 18 June 1897. p. 2. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ Karambati 2005, p. 26.

- ^ Karambati & Nikoltsios 2014, p. 57.

- ^ Dakin 1966, pp. 141–142.

- ^ Koliopoulos & Veremis 2010, pp. 47, 49.

- ^ Gounaris 2008, p. 185.

- ^ Koliopoulos & Veremis 2010, pp. 47–50.

- ^ a b Koliopoulos & Veremis 2002, p. 280.

- ^ a b Koliopoulos & Veremis 2010, p. 49.

- ^ Koliopoulos 2003, p. 16.

- ^ Gounaris 1995, pp. 410–411.

- ^ Koliopoulos & Veremis 2002, p. 337.

- ^ Koliopoulos & Veremis 2010, p. 79.

- ^ Livanios 2008, pp. 17–19.

- ^ Livanios 2008, pp. 17–9.

- ^ Kostopoulos 2016, pp. 143–146.

- ^ Karambati 2005, pp. 28, 34.

- ^ Gounaris 1997, p. 103.

- ^ Gounaris 1997, pp. 101–103.

- ^ Gounaris 1997, pp. 103–104, 108.

- ^ Dakin 1966, p. 142.

- ^ Dakin 1966, pp. 142–143.

- ^ Nestor 1962, p. 178.

- ^ a b c Gounaris 2007a, p. 192.

- ^ a b Kaliakatsos 2013, p. 54.

- ^ Dakin 1966, pp. 119–121.

- ^ a b Dakin 1985, p. 52.

- ^ a b c Dakin 1966, p. 143.

- ^ Dakin 1966, pp. 143–145.

- ^ Lithoxoou 2006, pp. 49, 54.

- ^ Koliopoulos & Veremis 2002, p. 281.

- ^ Gounaris 2007a, p. 191.

- ^ a b Kaliakatsos 2013, pp. 54, 71–72, 74–75 note 15.

- ^ Dakin 1966, pp. 114–6, 148–9.

- ^ Akhund 2014, p. 590.

- ^ a b c Dakin 1966, p. 149.

- ^ Akhund 2014, pp. 597–8.

- ^ Akhund 2014, pp. 598–900.

- ^ a b Akhund 2014, p. 599.

- ^ Dakin 1966, pp. 174, 163–4, 167, 168.

- ^ Dakin 1966, p. 168.

- ^ Akhund 2014, p. 598.

- ^ a b c d Dakin 1966, pp. 175–6.

- ^ a b Mela 1992, p. 189.

- ^ Karambati 2005, p. 23.

- ^ Karambati & Nikoltsios 2014, p. 65.

- ^ Karambati 2005, p. 36.

- ^ Karambati 2005, pp. 35–6.

- ^ Karambati 2005, p. 31, 39.

- ^ Mela 1992, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Karambati 2005, p. 34.

- ^ Dakin 1966, pp. 176–7.

- ^ Koliopoulos 1999a, pp. 156–7.

- ^ Kostopoulos 2018a.

- ^ Dakin 1966, pp. 177–9.

- ^ Karambati & Nikoltsios 2014, p. 67.

- ^ a b Gounaris 1997, p. 108.

- ^ Mela 1992, p. 260.

- ^ Dakin 1966, p. 177.

- ^ Karambati et al. 2009, p. 100, note 80.

- ^ Karambati & Nikoltsios 2014, pp. 69–71.

- ^ Vassiliadou 2019, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Dakin 1966, p. 179.

- ^ a b Karambati & Nikoltsios 2014, p. 71.

- ^ a b Dakin 1966, pp. 179–80.

- ^ Karambati 2005, pp. 36, 38–39.

- ^ Karambati & Nikoltsios 2014, p. 75.

- ^ Dakin 1966, pp. 180–1.

- ^ Dakin 1966, pp. 179, 181.

- ^ Gounaris 2007a, pp. 192–3.

- ^ Dakin 1966, p. 180.

- ^ Dakin 1966, pp. 182–3.

- ^ Andreou 2002, pp. 157–8, 166, 169.

- ^ Gounaris 2007a, p. 193.

- ^ a b Kaoudis 1992, pp. 19–21, note 35.

- ^ a b c d e Dakin 1966, p. 184.

- ^ Kaoudis 1992, p. 46, note 154.

- ^ Kaoudis 1992, p. 21, 17.

- ^ Karambati 2005, pp. 39–42.

- ^ Gounaris 1997, pp. 104, 108.

- ^ Karambati et al. 2009, pp. 240–1, note 125.

- ^ a b "Συλλογή φωτογραφιών - ID: 57082". Foundation of the Museum for the Macedonian Struggle. Archived from the original on 2020-02-05. Retrieved 2017-04-03.

- ^ a b c Gounaris 2002, p. 8.

- ^ Traykova 2003, p. 105.

- ^ Mela 1992, pp. 316, 330–333.

- ^ Lithoxoou 2006, pp. 85–6.

- ^ Karambati 2004, p. 12.

- ^ Karambati 2005, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Koliopoulos & Veremis 2002, p. 213.

- ^ Gounaris 1997, p. 107.

- ^ Lithoxoou 2006, p. 87.

- ^ a b Dakin 1966, p. 185.

- ^ Mela 1992, p. 348.

- ^ Karavitis 2008, p. 65.

- ^ Lithoxoou 2006, pp. 91, 92.

- ^ Dakin 1966, pp. 185, 128.

- ^ Modis 2007, p. 177.

- ^ Mela 1992, p. 383.

- ^ Koliopoulos 1999b, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Koliopoulos 1997, p. 44.

- ^ Livanios 1999, p. 216.

- ^ Karambati 2000, p. 26.

- ^ Mela 1992, pp. 385–386, Dakin 1966, p. 187, Traykova 2003, p. 107.

- ^ a b Livanios 1999, pp. 206–208.

- ^ Traykova 2003, p. 108.

- ^ Dakin 1966, p. 186, Traykova 2003, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Karambati 2005, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Mela 1992, p. 388.

- ^ Dakin 1966, p. 188, Traykova 2003, p. 109.

- ^ Lithoxoou 2006, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Gounaris 2005, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Traykova 2003, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Lithoxoou 2006, p. 98.

- ^ Traykova 2003, p. 109, Mela 1992, p. 390.

- ^ Traykova 2003, p. 110, Dakin 1966, p. 188, Karavitis 2008, pp. 86–91.

- ^ Traykova 2003, p. 110, Dakin 1966, p. 188.

- ^ Traykova 2003, p. 110, Dakin 1966, pp. 188–189, Mela 1992, p. 258.

- ^ Karambati & Nikoltsios 2014, p. 83.

- ^ Kleidis 1984, p. 127.

- ^ For Melas' unfinished cf. Hellenic Army History Directorate 1979, pp. 331–338.

- ^ Traykova 2003, pp. 121–122.

- ^ Dakin 1966, p. 189, Traykova 2003, p. 111.

- ^ a b Dakin 1966, p. 189.

- ^ Traykova 2003, pp. 119–121.

- ^ Dakin 1966, pp. 189–190, Kaoudis 1992, pp. 13, 17, 62 note 188.

- ^ Kaoudis 1992, pp. 46 note 154, 91 note 182.

- ^ Kaoudis 1992, pp. 12, 60-61 note 182, 65 note 197, 68 note 208.

- ^ Traykova 2003, pp. 118–119.

- ^ a b Dakin 1966, p. 190.

- ^ a b c Ios 2013a.

- ^ Traykova 2003, p. 118.

- ^ Gounaris 2005, p. 38.

- ^ a b c d e f Gounaris 2004, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d Ios 2004b.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cite error: The named reference

Dakin190was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Brancoff 1905, pp. 182–3: "67. Statichta: 960 Bulgares Exarchistes."

- ^ Kaoudis 1992, pp. 11, 21 note 35, 71, 73 note 224.

- ^ Lithoxoou 2006, p. 105, "Ce qui dit Hilmi pacha. Interview du "vice-roi" de Macédoine". Le Matin. 27 November 1904. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ a b Gounaris 2004, pp. 14–16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ios 2004a.

- ^ Gounaris 2004, p. 15.

- ^ Mela 1992, pp. 413–414.

- ^ Gounaris 2004, pp. 15–18.

- ^ a b c d e Gounaris 2004, p. 16.

- ^ a b Karavangelis 1993, pp. 64–66.

- ^ a b Mela 1992, p. 425.

- ^ Mela 1992, pp. 418–419.

- ^ a b c Gounaris 2004, p. 17.

- ^ Karakasidou 2004, pp. 214–5.

- ^ Mela 1992, p. 427.

- ^ Karambati et al. 2009, p. 287-288.

- ^ a b Karakasidou 2004, p. 197.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Gounaris2004-14was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Gounaris 2007a, p. 193, Dakin 1966, p. 192-3.

- ^ Theodosopoulou 2004, p. 26-7.

- ^ a b c Gounaris 2002, p. 13.

- ^ "Κωστής Παλαμάς: Παύλος Μελάς". Retrieved 2018-12-08.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Koulouri 2022, p. 161.

- ^ Theodosopoulou 2004, p. 28-29.

- ^ Christianopoulos 2004, pp. 31–54.

- ^ Christianopoulos 2004, pp. 57.

- ^ Stathatos 2016, p. 34.

- ^ Gounaris 2004, p. 19.

- ^ Koliopoulos 2004, p. 20.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Gounaris-φωτοwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Koliopoulos 2004, p. 22.

- ^ Karakasidou 2004, p. 204.

- ^ Μιχαηλίδης 2011, p. 40, Gounaris 2007b, p. 225.

- ^ Gounaris 2005, p. 37, σημ. 21.

- ^ Koliopoulos & Veremis 2010, p. 64, Koliopoulos & Veremis 2002, p. 212-3, Koliopoulos 2004, p. 20, 22.

- ^ a b Kostopoulos 2011.

- ^ Gounaris 2004, p. 16, Mela 1992, p. 483.

- ^ Kostopoulos 2006, p. 406-7.

- ^ Koulouri 2022, pp. 162–163.

- ^ "Πανδέκτης: Statista -- Melas". Retrieved 2018-12-08.

- ^ Gounaris 1990, pp. 327–9, 334–5, Tsironis 2014, p. 120-1, 122, σημ. 31, 151-2.

- ^ Psyllaki 2013, pp. 7, 9.

- ^ Kostopoulos 2006, p. 409.

- ^ Ios 2000.

- ^ Gounaris 2004, p. 177-178.

- ^ Theodosopoulou 2004, p. 28.

- ^ Karakasidou 1997, p. 91.

- ^ Theodosopoulou 2004, p. 28.

- ^ Karambati & Nikoltsios 2014, p. 9-10.

- ^ Karambati 2005, pp. 19–23.

- ^ Theodosopoulou 2004, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Theodoridis 2006, p. 202.

- ^ a b c Karakasidou 2004, p. 207.

- ^ a b c Kostopoulos 2019.

- ^ Karalis 2012, p. 175.

- ^ "Pavlos Melas (1973)". IMDb. Retrieved 2018-12-05.

- ^ Κωστ.(όπουλος) 2013.

- ^ a b Valden 2009, p. 505.

- ^ Karakasidou 2004, p. 208.

- ^ ΦΕΚ A 46 - 11.3.1969. 1969-03-11. p. 460. Retrieved 2022-05-18.

- ^ Karakasidou 2004, p. 204, 207.

- ^ Danforth 2003, pp. 361–362.

- ^ Tziampiris 2000, p. 55, σημ. 28.

- ^ "Η συλλογή του μουσείου". Ίδρυμα Μουσείου Μακεδονικού Αγώνα. Archived from the original on 2020-06-08. Retrieved 2020-03-20.

- ^ "Στους 14 κλειδώνουν οι δήμοι της Θεσσαλονίκης". VORIA.gr. 17-05-2010. Retrieved 19-05-2022.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "Ιστορικοί τόποι - Δήμος Παύλου Μελά - Σταυρούπολη Πολίχνη Ευκαρπία". Retrieved 2022-05-19.

- ^ Psarras 2018, p. 142.

- ^ Vasilopoulou & Halikiopoulou 2015, p. 75.

- ^ Ellinas 2020, p. 84.

- ^ "Η Αθήνα στον παλμό του συλλαλητηρίου". Η Καθημερινή. 04-02-2018. Retrieved 09-01-2022.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Συκκά, Γιώτα (13-11-2009). "Σχέδιο σωτηρίας της οικίας Παύλου Mela". Η Καθημερινή. Retrieved 15-11-2020.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "Αποκαθίσταται η οικία του Παύλου Μελά - Θα παραδοθεί στη Σχολή Ευελπίδων". 31-05-2020. Retrieved 19-05-2022.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help)

Sources

[edit]- "Παύλος Μελάς. Ένας αιώνας μνήμης" [Pavlos Melas. A century of memory]. Επτά Ημέρες (in Greek). Athens: Kathimerini. 17 October 2004.

- Gounaris, Vasilis K. "Το μοιραίο δεκαήμερο". In Επτά Ημέρες (2004), pp. 14–19.

- Karambati, Persefoni G. "Ο Μελάς μέσα από την πένα του". In Επτά Ημέρες (2004), pp. 11–13.

- Koliopoulos, Ioannis S. "Η «αναβίωση» του κλεφταρματολισμού". In Επτά Ημέρες (2004), pp. 20–22.

- Liontis, Kostis. "Ερασιτέχνης φωτογράφος". In Επτά Ημέρες (2004), p. 10.

- Theodosopoulou, M. "Απήχηση στη λογοτεχνία". In Επτά Ημέρες (2004), pp. 26–29.

- Akhund, Nadine (2014). "Stabilizing a Crisis and the Mürzsteg Agreement of 1903: International Efforts to Bring Peace to Macedonia". Hungarian Historical Review. 3 (3): 587–608.

- Andreou, Andreas P. (2002). Κώττας (1863-1905) (in Greek). Athens: Livanis.

- Brancoff, D.M. (1905). La Macédoine et sa population chrétienne [Macedonia and her Christian Population] (in French). Paris: Plon.

- Christianopoulos, Dinos (2004). Ο Παύλος Μελάς σε ποιήματα Μακεδόνων ποιητών. Εκατό χρόνια από το θάνατό του [Pavlos Melas in Poems of Macedonian Poets. Hundred Years After His Death] (in Greek). Thessaloniki: Museum for the Macedonian Struggle.

- Dakin, Douglas (1966). The Greek Struggle in Macedonia 1897-1913. Thessaloniki: Institute for Balkan Studies.

- Dakin, Douglas (1985). Μακεδονικός Αγώνας [Macedonian Struggle] (in Greek). Athens: Ekdotiki Athinon.

- Danforth, Loring M. (2003). "Alexander the Great and the Macedonian Conflict". In Roisman, Joseph (ed.). Brill's Companion to Alexander the Great. Leiden: Brill. pp. 347–364.

- Dragoumis, Ion (2000). Petsivas, Giorgos (ed.). Τὰ Τετράδια τοῦ Ἴλιντεν [The Ilinden Notebooks] (in Greek). Athens: Petsivas.

- Ellinas, Antonis A. (2020). Organizing Against Democracy. The Local Organizational Development of Far Right Parties in Greece and Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gianoulopoulos, Giannis (2003). Η ευγενής μας τύφλωσις: Εξωτερική πολιτική και "εθνικά θέματα" από την ήττα του 1897 έως τη μικρασιατική καταστροφή [Our Noble Blindness: Foreign Policy and "National Affairs" from the Defeat of 1897 to the Asia Minor Disaster] (in Greek) (Fourth ed.). Athens: Vivliorama.

- Gounaris, Vasilis K. (1990). "Βουλευτές και Καπετάνιοι: Πελατειακές σχέσεις στη μεσοπολεμική Μακεδονία" [Parliamentarians and Captains: Clientelistic Relationships in Post-War Macedonia]. Ελληνικά (in Greek). 41: 313–335.

- Gounaris, Basil G. (1995). "Social Cleavages and National "Awakening" in Ottoman Macedonia". East European Quarterly. 29 (4): 409–426.

- Gounaris, Basil C. (1997). "Social Gatherings and Macedonian Lobbying: Symbols of Irredentism and Living Legends in Early Twentieth-Century Athens". In Carabott, Philip (ed.). Greek Society in the Making, 1863–1913: Realities, Symbols and Visions. Aldershot: Ashgate. pp. 99–112.

- Gounaris, Vasilis K. (2002). Ο Μακεδονικός αγώνας μέσα από τις φωτογραφίες του, 1904-1908 [The Macedonian Struggle Through its Photographs, 1904-1908] (in Greek). Athens and Veroia.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Gounaris, Basil C. (2004b). "Social Dimensions of Anticommunism in Northern Greece, 1945-50". In Carabott, Philip; Thanasis D., Thanasis (eds.). The Greek Civil War: Essays on a Conflict of Exceptionalism and Silences. Aldershot: Ashgate. pp. 175–186.

- Gounaris, Basil C. (2005). "Preachers of God and Martyrs of the Nation. The Politics of Murder in Ottoman Macedonia in the Early Twentieth Century". Balkanologie. 9: 31–43. Archived from the original on 2017-12-30. Retrieved 2018-12-02.

- Gounaris, Basil C. (2007a). "National Claims, Conflicts and Developments in Macedonia, 1870-1912". In Koliopoulos, Ioannis (ed.). The History of Macedonia (PDF) (in Greek). Thessaloniki: Museum of the Macedonian Struggle. pp. 183–213. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-09-10. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- Gounaris, Vasilis (2007b). Τα Βαλκάνια των Ελλήνων: από το Διαφωτισμό έως τον Α' Παγκόσμιο Πόλεμο [The Balkans of the Greeks: From Enlightenment to World War I] (in Greek). Thessaloniki: Epikentro.

- Gounaris, Vasilis K. (2008). "Η Μακεδονία των Ελλήνων: Από το Διαφωτισμό έως τον Α΄ Παγκόσμιο Πόλεμο". In Giannis Stefanidis; Vlasis Vlasidis; Evangelos Kofos (eds.). Μακεδονικές ταυτότητες στο χρόνο: Διεπιστημονικές προσεγγίσεις [Macedonian Identities through Time: Interdisciplinary Approaches] (in Greek). Athens: Patakis. pp. 185–210.

- Grigoratou, Andriani; Melpidou, Angeliki (2015). "Η μαχητική και αποφασιστική Ζωή Μελά (30/11/1898 - 21/12/1996)" (PDF). Ενημερωτικό Δελτίο. Greek Society of Clinical Chemistry and Clinical Biochemistry: 9–39. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-24. Retrieved 2020-03-18.

- Hellenic Army History Directorate (1979). Ο Μακεδονικός Αγών και τα εις Θράκην γεγονότα [The Macedonian Struggle and Events in Thrace] (in Greek). Athens.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Hellenic Army History Directorate (1993). Ο Ελληνοτουρκικός Πόλεμος του 1897 [The Greco-Turkish War of 1897] (in Greek). Athens. OCLC 880458520.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Ios (26 November 2000). "Ο εμφύλιος των προτομών" [The civil war of the busts]. Eleftherotypia (in Greek). Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- Ios (10 October 2004). "Ποιος σκότωσε τον Παύλο Μελά; Πρώτο Μέρος" [Who killed Pavlos Melas? First Part]. Eleftherotypia (in Greek). Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- Ios (10 October 2004). "Ποιος σκότωσε τον Παύλο Μελά; Δεύτερο Μέρος" [Who killed Pavlos Melas? Second Part]. Eleftherotypia (in Greek). Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- Ios (14 July 2013). "Και ο παντρεμένος είχε ψυχή. Ο άγνωστος έρωτας του Παύλου Μελά" [Even the married man had a soul. The unknown love affair of Pavlos Melas]. Efimerida ton Syntakton (in Greek).

- Ios (11 October 2013). "Από τη χρεωκοπία στον αυταρχισμό. Η γέννηση του «βαθέος κράτους»" [From bankruptcy to authoritarianism. The birth of the "deep state"]. Efimerida ton Syntakton (in Greek).

- Kaliakatsos, Michalis (2013). "Ion Dragoumis and 'Machiavelli': Armed struggle, Hellenization and propaganda in Macedonia and Thrace (1903-1908)". Journal of Modern Greek Studies. 31 (1): 53–84. doi:10.1353/mgs.2013.0008.