User:Dontuseurrealname/sandbox/Julius Caesar (rewrite)

The Tragedy of Julius Caesar (First Folio title: The Tragedie of Ivlivs Cæsar), often known simply as Julius Caesar, is a historical play and tragedy written by English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. First performed in 1599, it is based on the real-life events of the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BCE, as described by the Greek historian Plutarch in his book Parallel Lives. The play mainly follows the senator Marcus Junius Brutus, as he joins Gaius Cassius Longinus on a covert conspiracy to assassinate Caesar on the Ides of March, and later have to deal with the Caesarian forces of Gaius Octavius and Mark Antony as they attempt to revenge Caesar's death.

The play was performed many times after its initial release, notably Orson Welles' 1937 rendition in the Mercury Theatre, which mirrored the events of Nazi Germany prior to the second World War.

Plot[edit]

Act I[edit]

Two Roman aristocrats, named Marullus and Flavius, encounter a group of commoners in the streets celebrating the upcoming feast of Lupercalia and the military conquests of Julius Caesar. The two then harass the group for being out on the streets during work hours and for supporting Caesar when, in the recent past, the general public was in support of Caesar's rival Pompey, whereto they command them to flee and cry in the Tiber. Afterwards, the two agree to defame the imagery of Caesar populating the city of Rome, whereafter they go their separate ways.

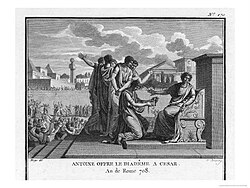

The act cuts to Caesar arriving before a group of senators, where he is stopped by a mysterious soothsayer who warns him to "Beware the Ides of March", which Caesar swiftly dismisses. All of the senators leave, save for Brutus and Cassius, who stay behind to talk privately. Cassius subtly manipulates Brutus to not trust Caesar, and highlights instances during his campaigns where he proved himself weak; he recounts a story where Caesar nearly drowned in the Tiber, saved by Cassius himself, and another where he fell severely ill during a campaign in Hispania (Spain). The rest then reappear, where Caesar mentions to Mark Antony that he is highly distrustful of Cassius and sees him as a dangerous man. They all leave once again, except for Casca, who is pulled by the cloak by Cassius. Casca details how he publicly offered Caesar a crown three times, which he repeatedly rejected, before suffering from a epileptic seizure in the marketplace. Cassius, once again, implies to Brutus that Caesar is weaker than the deific figure he portrays himself to be. After Brutus and Casca exit, Cassius has a lengthy soliloquy where he admits to himself of his true plans: to compose fake letters of praise to Brutus and send them to him, as if they were from several people, to boost his ego.

Meanwhile, as a raging storm engulfs Rome, Casca reports to Cicero that he had seen a number of strange omens, such as a lion on the Capitoline Hill and a slave whose hand was perpetually burning with fire. Casca comments that Caesar will be at the Capitol in short time, after which he leaves and Cassius, who partook to the streets, meets with Cicero. After Cicero exits, Cassius then meets with Cinna and Casca, and the two plot to manipulate Brutus into joining their conspiracy; during this conversation, it is revealed by Casca that the Roman senate plans, in their next meeting at the Theatre of Pompey, to formally coronate Caesar as king in all Roman provinces except for Italy itself. Cassius then orders Cinna to lay one of his fake letters on the chair of the praetor, so that Brutus can read it when he inevitably encounters it.

Act II[edit]

In the evening of March 14, while in his private garden, Brutus decides that Caesar must die to prevent him from becoming an unchecked tyrant. His servant, Lucius, then presents him with one of Cassius' letters, unbeknownst to the two. The letter makes reference to the semi-legendary overthrow of Lucius Tarquinius Superbus and the Roman kingdom at the hand of Lucius Junius Brutus, from whom Marcus Brutus claimed descendance, and implies that he was to recall to his ancestor and overthrow the tyrannical Caesar. After reading the letter, Lucius reappears and states that there is a group of hooded men are at his door, which are revealed to Brutus to be the conspiracy in full. Rumors that Caesar will not appear to the Theatre of Pompey begin to circulate, and Decius Brutus claims that he can sway Caesar to attend the meeting. After the conspiracy leaves Brutus' house, his wife Portia enters highly distressed about Brutus' reluctance to inform her about his clandestine operations. She claims that she is not with wife, but rather his mistress, and proceeds to stab herself in the leg as a show of her mental fortitude.

That same night, Caesar's wife Calpurnia awakes from her sleep after having a vivid nightmare of Caesar being stabbed in multiple places and the Romans relishing in the blood pouring out of his wounds. He takes the nightmare as a sign to not attend the day's senate meeting, and decides to stay with Calpurnia. Decius, however, manages to sway Caesar to join them at the meeting, stating that the senate plans to crown him as king.

Act III[edit]

Upon Caesar's arrival to the Theatre, a common Roman named Artemidorus attempts to hand him a letter detailing the conspiracy, but he swiftly rejects it. Meanwhile, Cassius and Brutus make their way to the Capitol and express their paranoia about the conspiracy leaking, even wrongfully suspecting senator Popilius Lena as being against them. Expecting to be crowned king, Caesar begins to publicly act rashly against Metellus Cimber after he implores him to free his imprisoned brother, Publius, and thereon monologues about his superiority in society. As Caesar demands all of the senators to kneel before him, Casca signals to the others to attack, and the rest of the conspirators proceed to stab him. Brutus is the last to act, wherebefore Caesar remarks "Et tu, Brute?" (roughly translated in English as "You too, Brutus?") and falls dead on the floor.[1] The conspirators then revel in his death, and plan to proclaim on the streets that liberty had been realized, whereafter they exit.

References[edit]

- ^ Henle, Robert J., S.J. Henle Latin Year 1 Chicago: Loyola Press 1945