User:Garygo golob/Brda dialect/sandbox

| Brda dialect | |

|---|---|

| ˈbrìːško naˈrìeːči̯e | |

| Pronunciation | ˈbɾíːʃkɔ naˈɾíɛːt͡ʃi̯ɛ |

| Native to | Slovenia, Italy |

| Region | Gorizia Hills |

| Ethnicity | Slovenes |

Early forms | Northwestern Slovene dialect

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

Brda dialect | |

| South Slavic languages and dialects |

|---|

This article uses Logar transcription.

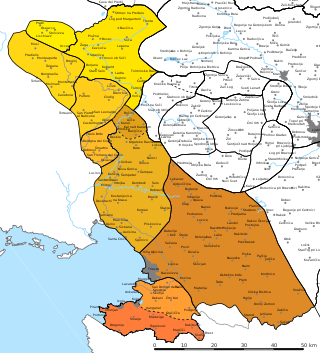

The Brda dialect (Slovene: briško narečje [ˈbɾíːʃkɔ naˈɾéːt͡ʃjɛ],[1] briščina[2]) is a Slovene dialect, known by extreme vowel reduction of final consonants, spoken in Gorizia Hills in Slovenia and Italy. It borders Natisone Valley dialect to the north, Karst dialect to the east and Friulian to the west. The dialect belongs to the Littoral dialect group, and evolved from Veneitian-Karst dialect plane.[3][4]

It is spoken on a territory with around 6,000 Slovene speakers, most of whom have a degree of knowledge of the dialect.

Geographical distribution[edit]

The dialect is spoken west of the Soča River in the Gorizia Hills, extending from Lig in the north, along the Soča river in the east, up to Oslavia/Oslavje and Gradiscutta/Gradiščula in the south and to Dolegna del Collio/Dolenje in the west.

In Slovenia, the dialect is spoken in most of the territory of the Municipality of Brda (except for its northwesternmost strip, where the Natisone Valley dialect is spoken) and in the westernmost part of the Municipality of Kanal ob Soči. Notable settlements include Hum, Kojsko, Kozana, Šmartno, Medana, Dobrovo, Plave and Anhovo.[3]

In Italy, it is spoken in the northeastern area of the Province of Gorizia, in the municipalities of San Floriano del Collio/Števerjan, and in part of the municipalities of Cormons/Krmin and Dolegna del Collio/Dolenje. It is also spoken in the western suburbs of the town of Gorizia (Piedimonte del Calvario/Podgora, Piuma/Pevma, Oslavia/Oslavje).[3]

Accentual changes[edit]

Brdo dialect lost pitch accent, unlike the nearby Natisone Valley and Torre Valley dialects, however some southeastern microdialects (especially around Kojsko) have developed new tonal oppositions, which are morphologically correlated. These dialects distinguish between circumflex and acute accent on long vowels, short ones always have the same pitch. Dialect is in the late stages of losing length oppositions.[5] It has undergone two accent shifts: the *ženȁ → *žèna and *məglȁ → *mə̀gla accent shift.[6]

Phonology[edit]

Brdo dialect has mostly uniform sounds for long vowels, however for short vowels, sounds can vary drastically. Vowel *ě̄ turned into iːe. Vowels *ę̄ and *ā are now both pronounced as aː, the first one in Kozana as oː if not followed or preceded by a nasal consonant. Vowel *ē turned into eː. Vowel *ǭ turned into oː in most microdialects, some near Karst dialect pronounce it as uːo, while *ō is a diphthong uːo in most microdialects. Alpine Slavic *ī is still pronounced as iː and *ū is still pronounced as *uː. Syllabic *ł̥̄ turned into uː and *r̥̄ turned into ər. Newly accented *ə is pronounced as *əː, while long *ə̄ is pronounced as aː.[7]

In closed syllables, short *è turned into eː, *ò into oː, and *ì, *ù and *ę̀ into əː, lengthening in the process. The only unlengthened vowel is *à, which turned into ḁ around Kojsko, but might have also turned into a long one in other microdialects. Vowel *o before the stressed syllable usually turned into u, although it also changes into ḁ. Vowels *a and *i before the stress turn into e. Vowel *ě after the stress turned into i. Final *i, *u, *ę and *ǫ are not pronounced anymore, the only exception is third person singular ending -i (e. g. (on) vȋdi → vìːdẹ).[8]

Consonant changes are pretty common for littoral dialects. Palatal *ń and *ĺ are pronounced in most microdialects the same, the latter turned into i̯ in Kozana and west from that. Consonant *g turned into ɣ and into x at the end of a word. Final m turned into n in the west. Clusters čr-, čl- and pš- turned into čer-, čel- and peš-, respectively.[9][10]

Morphology[edit]

Brdo dialect has separate dual forms only in masculine o-stems nominative, vocative and accusative case; elsewhere they merged with the plural forms. Special case is second person plural, where ending is -ta (from the dual form) and ending -te is used only for vikanje. It uses long infinitive, although final -i is dropped, but accent stays the same. Neuter nouns are feminized in plural.[5]

It also has different endings for third person plural form of present tense. It is -i̯o in the west, but -i̯ in the east.

The biggest changes to morphology happened around Kojsko, where declension fundamentally changed. Because of vowel reduction, most endings were lost, so instead different cases have different tone – either circumflex or acute – which helps determine the case.[5]

| Singular | Dual | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominatve | -̑ | -̑a | -́ |

| Genitive | -̑a | -̑u | |

| Dative | -́ | -̑em ~ -̑əm | |

| Accusative | nom or gen | -̑a | -́ |

| Locative | -́ | -̑ix | |

| Instrumental | -̑əm | -̑əm ~ -áːm | |

| Vocative | -̑ | -̑a | -́ |

| Singular | Dual | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominatve | -̑o | -́ | |

| Genitive | -̑a | -̑ | |

| Dative | -́ | -̑em ~ -̑əm | |

| Accusative | -̑o | -́ | |

| Locative | -́ | -̑ix | |

| Instrumental | -̑əm | -̑əm ~ -áːm | |

| Vocative | -̑o | -́ | |

| Singular | Dual | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominatve | -̑a | -́ | |

| Genitive | -́ | -̑ | |

| Dative | -́ | -̑em | |

| Accusative | -́ | -́ | |

| Locative | -́ | -̑ix | |

| Instrumental | -́ | -áːm | |

| Vocative | -̑a | -́ | |

Similar thing also happens with i-stem nouns when the ending is -i.

References[edit]

- ^ Smole, Vera. 1998. "Slovenska narečja." Enciklopedija Slovenije vol. 12, pp. 1–5. Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga, p. 2.

- ^ Rigler, Jakob. 1986. Razprave o slovenskem jeziku. Ljubljana: Slovenska matica, p. 175.

- ^ a b c "Karta slovenskih narečij z večjimi naselji" (PDF). Fran.si. Inštitut za slovenski jezik Frana Ramovša ZRC SAZU. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ Šekli (2018:327–328)

- ^ a b c Logar (1996:74–77)

- ^ Šekli (2018:310–314)

- ^ Logar (1996:72–74)

- ^ Logar (1996:74–75)

- ^ Logar (1996:74)

- ^ Toporišič, Jože. 1992. Enciklopedija slovenskega jezika. Ljubljana: Cankarjeva založba, p. 12.

Bibliography[edit]

- Logar, Tine (1996). Kenda-Jež, Karmen (ed.). Dialektološke in jezikovnozgodovinske razprave [Dialectological and etymological discussions] (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Znanstvenoraziskovalni center SAZU, Inštitut za slovenski jezik Frana Ramovša. ISBN 961-6182-18-8.

- Šekli, Matej (2018). Legan Ravnikar, Andreja (ed.). Topologija lingvogenez slovanskih jezikov (in Slovenian). Translated by Plotnikova, Anastasija. Ljubljana: Znanstvenoraziskovalni center SAZU. ISBN 978-961-05-0137-4.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)