User:Garygo golob/Inner Carniolan dialect/sandbox

| Inner Carniolan dialect | |

|---|---|

| ˈnuːətrańsku naˈreːi̯či̯e | |

| Pronunciation | ˈnuːətɾaɲsku naˈɾɛːi̯t͡ʃjɛ |

| Native to | Slovenia, Italy |

| Region | Western Inner Carniola, upper Vipava Valley, southern Kras |

| Ethnicity | Slovenes |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | Southeastern Slovene dialect

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

Inner Carniolan dialect | |

| South Slavic languages and dialects |

|---|

This article uses Logar transcription.

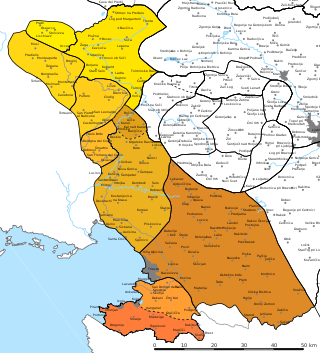

The Inner Carniolan dialect (Slovene: notranjsko narečje [ˈnòːtɾanskɔ naˈɾéːt͡ʃjɛ],[1] notranjščina[2]) is a Slovene dialect very close to Lower Carniolan dialect, but with newer accent shifts. It is spoken in a relatively large area, extending from western Inner Carniola up to Trieste in Italy, also covering the upper Vipava Valley and the southern part of the Karst Plateau. The dialect borders Lower Carniolan dialect to the east, Črni Vrh and Horjul dialects to the north, Karst dialect to the northwest, Istrian dialect to the southwest, as well as Middle Chakavian and Northern Chakavian to the south.[3][4] The dialect belongs to the Littoral dialect group, and evolved from Lower Carniolan dialect plane.[3][5]

Geographic distibution[edit]

The dialect is spoken in most of the municipalities of Postojna, Pivka, Ilirska Bistrica, Divača, Hrpelje-Kozina, Vipava, in most areas of the municipalities of Sežana and Ajdovščina, as well as the Municipalities of Monrupino and Sgonico in Italy, and in many Slovene-inhabited villages in the Municipality of Trieste (most notably in Opicina/Opčine). Geographically, dialect is bounded by Javorniki hills in the east, national border in the southeast, in the southwest up to Gradišče pri Materiji, western up to Slavnik and Kozina, in Italy to the coast, and northermost up to Predmeja.[6][3]

Accentual changes[edit]

Inner Carniolan dialect has undergone more accent shifts than Lower Carniolan dialect on the other side because of the influence of other Littoral dialects.[7] It had undergone four accent shifts: *ženȁ → *žèna, *məglȁ → *mə̀gla, *visȍk → vìsok, and *ropotȁt → *ròpotat.[8] Some southeastern microdialects have also partially undergone *sěnȏ / *prosȏ → *sě̀no / *pròso accent shift (e. g. imȃ → ˈiːma in Jelšane microdialect), although most of these changes are morphologically correlated.[9] It also lost pitch accent and is in the process of losing distinction of long and short vowels as the short ones are lengthening.[6][10]

Phonology[edit]

In terms of phonology, Inner Carniolan dialect is very similar to Lower Carniolan dialect. Diphthongs mostly stayed like that or have monophthongized in some parts, particularly near Karst and Črni Vrh dialects, which come from different dialect bases and their diphthongs are therefore often different, which led to monphthongization on bordering microdialects on both sides. Alpine Slovene *ě̄ and non-final *ě̀ show this phenomenon the most. In most dialects, it is still pronounced as a diphthong eːi̯, but in microdialects, such as Sežana, Dutovlje, Vrabče, Štjak and nortwestern from that, as well as microdialects around Predmeja and Otlica, it has monophthongized into eː. Similar assimilation also happened on Brkini and northern Pivka basin. In southern Pivka basin, however, diphthong dissimilated into ȧːi̯, ạːi̯, or oːi̯ going south. In contrast to *ě, Alpine Slavic *ę̄, non-final *ę̀, *ē and non-final *è are pronounced quite similarly throughout the dialect, staying a diphthong iːe or slightly reduced to iːə. Similarly, *ǭ, *ò and non-final *ǫ̀ stayed as uːo or reduced to uːə. Non-final *ō turned into uː, but stayed a diphthong oːu before č, š, z, or s. *ī and *ā stayed mostly unchanged, but *ū turned into yː, except in words introduced later to the dialect, where it is still uː. Proto-Slavic *ł̥ turned into oːu̯.[11][12]

Palatal *ĺ and *ń stayed palatal, *tł changed to kł, *tl and *dl in l-participle simplified into l and *g turned into ɣ.[13]

Morphology[edit]

Dual forms are different from plural in nominative and accusative case only, verbs generally lost dual forms. There is tendency to fix accent when declining (i. e. for nouns to have fixed accent). Neuter gender is neither masculinized nor feminized, infinitive stem sometimes became the same as present stem. Verbs with two possible accents in infinitive have all l-participle forms accented as masculine singular form. Long infinitive was replaced by short one and verb endings -ta and -te alway get -s- infix (pˈriːdesta, ˈviːdiste). Imperative does not undergo č → c change.[14]

Southern microdialects do not have s-stem nouns anymore and they turned into o-stem. By doing so, if the accent was on the infix, it shifted one syllable to the left, a feature that also extended into the nominative case, where it originally did not have the infix: ˈkuːłu ˈkuːla for standard Slovene kolȏ kolẹ̑sa 'bicycle' in nominative and genitive singular, respectively.[15]

Vocabulary[edit]

Lexically, the dialect shows extensive influence from Romance languages.[6]

Sociolinguistic aspects[edit]

About 90,000 Slovene speakers live in the areas where the dialect is traditionally spoken. Although there are no precise statistics, it is likely that a large majority of them have some degree of knowledge of the dialect. This makes it the most widely spoken dialect in the Slovenian Littoral and among the 10 most spoken Slovene dialects.

In most rural areas, especially in the Vipava Valley and on the Karst Plateau, the dialect predominates over standard Slovene (or its regional variety). Differently from many other Slovene dialects, the Inner Carniolan dialect is commonly used in many urban areas, especially in the towns of Ajdovščina, Vipava, and Opicina (Italy). In the towns, where commuting to the capital, Ljubljana, is more common (Postojna), the dialect is being slowly replaced by a regional version of standard Slovene.

Culture[edit]

There is no distinctive literature in Inner Carniolan. However, features of the dialects are present in the texts of the Lutheran philologist Sebastjan Krelj (born in Vipava) and the Baroque preacher Tobia Lionelli (born in Vipavski Križ).

The folk rock group Ana Pupedan uses the dialect in most of its lyrics. The singer-songwriter Iztok Mlakar has also employed it in some of his chansons. The comedian and satirical writer Boris Kobal has used it in some of his performances, and so has the comedian Igor Malalan.

References[edit]

- ^ Smole, Vera. 1998. "Slovenska narečja." Enciklopedija Slovenije vol. 12, pp. 1–5. Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga, p. 2.

- ^ Logar (1996:65)

- ^ a b c "Karta slovenskih narečij z večjimi naselji" (PDF). Fran.si. Inštitut za slovenski jezik Frana Ramovša ZRC SAZU. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ Kapović, Mate (2015). POVIJEST HRVATSKE AKCENTUACIJE (in Croatian). Zagreb: Zaklada HAZU. pp. 40–46. ISBN 978-953-150-971-8.

- ^ Šekli (2018:335–339)

- ^ a b c Toporišič, Jože. 1992. Enciklopedija slovenskega jezika. Ljubljana: Cankarjeva založba, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Logar (1996:180)

- ^ Šekli (2018:310–314)

- ^ Jakop, Tjaša (2013). Govor vasi Jelšane (SLA T156) na skrajnem jugu notranjskega narečja (in Slovenian). Ljubljana. p. 143.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Šekli (2018:340)

- ^ Logar (1996:180–185)

- ^ Rigler (1986:108–115)

- ^ Logar (1996:185)

- ^ Logar (1996:185–187)

- ^ Rigler (2001:299–301)

Bibliography[edit]

- Logar, Tine (1996). Kenda-Jež, Karmen (ed.). Dialektološke in jezikovnozgodovinske razprave [Dialectological and etymological discussions] (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Znanstvenoraziskovalni center SAZU, Inštitut za slovenski jezik Frana Ramovša. ISBN 961-6182-18-8.

- Rigler, Jakob (1986). Jakopin, Franc (ed.). RAZPRAVE O SLOVENSKEM JEZIKU [Discussions about Slovene language] (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Bogo Grafenauer.

- Rigler, Jakob (2001). "1: Jezikovnozgodovinske in dialektološke razprave" [1: Linguohistorical and dialectological discussions]. In Smole, Vera (ed.). Zbrani spisi / Jakob Rigler [Collected essays / Jakob Rigler] (in Slovenian). Vol. 1. Ljubljana: Založba ZRC. ISBN 961-6358-32-4.

- Šekli, Matej (2018). Legan Ravnikar, Andreja (ed.). Topologija lingvogenez slovanskih jezikov (in Slovenian). Translated by Plotnikova, Anastasija. Ljubljana: Znanstvenoraziskovalni center SAZU. ISBN 978-961-05-0137-4.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)