User:Garygo golob/Torre Valley dialect/sandbox

| Torre Valley dialect | |

|---|---|

| Ter Valley dialect | |

| Native to | Slovenia, Italy |

| Region | Torre Valley, Breginjski kot |

| Ethnicity | Slovenes |

Early forms | Northwestern Slovene dialect

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

Torre Valley dialect | |

| South Slavic languages and dialects |

|---|

This article uses Logar transcription.

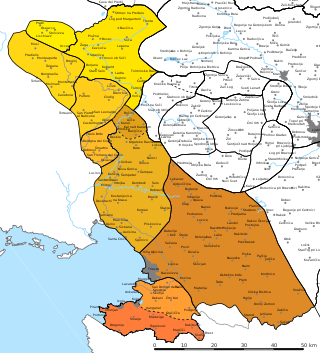

The Torre Valley dialect or Ter Valley dialect (tersko narečje,[1] terščina[2]) is the westernmost[3] and the most Romanized Slovene dialect[4] and is one of the most endangered dialects and is threatened with extinction.[5] It is also one of the most archaic Slovene dialects, together with Gail Valley and Natisone Valley dialects, which makes it interesting for typological research.[6] It is spoken mainly in Torre Valley in the Province of Udine in Italy, but also in western parts of Municipality of Kobarid, Slovene Littoral in Slovenia. Dialect borders Soča dialect to the east, Natisone Valley dialect to the southeast, Resian to the north, and Friulian to the southwest and west.[7] The dialect belongs to the Littoral dialect group, and evolved from Veneitian-Karst dialect plane.[8][9]

Geographical extension[edit]

The dialect is spoken mainly in northeastern Italy, in province of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, roughly along river Torre/Ter from Tarcento/Čenta upstream. It also extends far more than just that; it is bounded by Monti Musi/Mužci to the north, by Friulian plain to the west and south and by mountain Joanaz/Ivanec to the east, completely filling the area between Natisone Valley and Resian dialect. Dialect thus also extends into Slovenia, to Breginjski kot in Municipality of Kobarid, Slovene Littoral, being spoken in villages, such as Breginj, Logje and Borjana. Bigger settlements include Montefosca/Črni Vrh, Prossenicco/Prosnid, Canebola/Čenebola, Cergneu/Černjeja, Torlano/Torlan, Taipana/Tipana, Monteaperta/Viškorša, Vedronza/Njivica, Lusevera/Bardo, Torre/Ter, and Mužac/Musi.

Historically, it included the village of Pers (Slovene: Breg or Brieh), the westernmost ethnically Slovene village.[10][11]

Accentual changes[edit]

Torre Valley dialect retains pitch accent on long syllables, which are still longer than short syllables. It has undergone only one accent shift on most of the territory—the *sěnȏ > *sě̀no accent shift. However, microdialects dialects of Porzus/Porčinj, Prossenicco/Prosnid and Subit/Subid have also undergone *bàbica > *babìca and *zíma > *zīmȁ accent shifts, resulting in a new short stressed syllable. Microdialect of Subit/Subid still retains length on formerly stressed vowel after the latter shift.[12][13]

Phonology[edit]

Alpine Slavic and later lengthened *ě̄ turned into i(ː)e, in the south simplifying into iːə. Similarly, long *ō also turned into u(ː)o, simplifying into uːə in the south, while later lengthened *ò turned into ọː in the west, all the way up to åː in the south. Similarly, *ē also varies between ẹː and äː, but the distribution is more sporadic. Nasal *ę̄ and *ǭ evolved the same, but might have not merged with non-nasal counterparts in all microdialects. Syllabic *ł̥̄ turned into oːu~ọːu in the west and into uː in the east. Syllabic *r̥ turned into aːr in the west and ər in the east. Vowel reduction is not that common. Akanye is in some microdialects present for *ǫ̀ and *ę̀. Ukanye is more common and *ì simplified into ì̥ in the west and to ə in the east. In some microdialects, particularly the west, secondary nasalisation of vowels occurs from clusters vowel + final m/n.[14]

Eastern dialects simplified *g into ɣ, while in the west, it completely disappeared. In far west (e. g. Torre/Ter), alveolar and post-alveolar sibilants merged into one. Consonant *t’ mostly turned into ć. Palatal *ń is still palatal, and *ĺ turned into j.[14]

Morphology[edit]

Morphology of Torre Valley dialect is vastly different from that of Standard Slovene, mainly because of influence of Romance languages.

Neuter gender exists in singular, but is feminized in plural. Dual forms are limited to nominative and accusative case, while verbs do not have separate dual forms, although ending -ta is used for second person plural, and -te is reserved for vikanje. It has two future tenses: future I, formed with verb ti̥ẹ́ti̥ 'want' in present tense followed by infinitive, and future II, formed as future tense in Standard Slovene. It also has subjunctive, which is formed by ke + imperative form. Pluperfect still exists, as well as long infinitive. It also has -l, -n and -ć (equivalent to Standard Slovene -č) participle.[15]

Writing and vocabulary[edit]

The dialect was written already in the Cividale manuscript in 1479, but was later not used in written form.[5] Nowadays, because of the lack of language policy and Italianization, the dialect has a very reduced number of speakers and is threatened with extinction.[5] In 2009, a dictionary of the Torre Valley dialect was published, based on material collected mainly at the end of the 19th century, but also in the 20th century.[16]

References[edit]

- ^ Smole, Vera. 1998. "Slovenska narečja." Enciklopedija Slovenije vol. 12, pp. 1–5. Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga, p. 2.

- ^ Šekli, Matej. 2004. "Jezik, knjižni jezik, pokrajinski oz. krajevni knjižni jezik: Genetskojezikoslovni in družbenostnojezikoslovni pristop k členjenju jezikovne stvarnosti (na primeru slovenščine)." In Erika Kržišnik (ed.), Aktualizacija jezikovnozvrstne teorije na slovenskem. Členitev jezikovne resničnosti. Ljubljana: Center za slovenistiko, pp. 41–58, p. 52.

- ^ Jakopin, Franc (1998). "Ocene – zapiski – poročila – gradivo: Krajevna in ledinska imena gornje Terske doline" [Reviews – Notes – Reports – Materials: Place Names and Cadastral Place Names of the Upper Torre Valley] (PDF). Slavistična revija: časopis za jezikoslovje in literarne vede [Journal of Slavic Linguistics: Journal for Linguistics and Literary Studies] (in Slovenian). 46 (4). Slavic Society of Slovenia: 389. ISSN 0350-6894.

- ^ Logar, Tine (1970). "Slovenski dialekti v zamejstvu". Prace Filologiczne. 20: 84. ISSN 0138-0567.

- ^ a b c "Tersko narečje". Primorski dnevnik (in Slovenian). 2010. ISSN 1124-6669.

- ^ Pronk, Tijmen (2011). "Narečje Ziljske doline in splošnoslovenski pomik cirkumfleksa" [The Gail Valley Dialect and the Common Slovene Advancement of the Falling Tone] (PDF). Slovenski jezik [Slovene Linguistic Studies] (in Slovenian) (8): 15. ISSN 1408-2616. COBISS 33260845.

- ^ "Karta slovenskih narečij z večjimi naselji" (PDF). Fran.si. Inštitut za slovenski jezik Frana Ramovša ZRC SAZU. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ "Karta slovenskih narečij z večjimi naselji" (PDF). Fran.si. Inštitut za slovenski jezik Frana Ramovša ZRC SAZU. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ Šekli (2018:327–328)

- ^ Bandelj, Andrej, & Primož Pipan. 2014. Videmsko. Ljubljana: Ljubljansko geografsko društvo, p. 93.

- ^ Gorišek, Gorazd. 2011. Med slovenskimi rojaki v Italiji. V gorah nad Tersko dolino. Planinski vestnik 116(5) (May): 41–44, p. 44.

- ^ Šekli (2018:310–314)

- ^ Ježovnik (2019:128–135)

- ^ a b Ježovnik (2019:75–208)

- ^ Ježovnik (2019:451–505)

- ^ Spinozzi Monai, Liliana (2009). Il Glossario del dialetto del Torre di Jan Baudouin de Courtenay [The Glossary of the Torre Dialect by Jan Baudouin de Courtenay] (in Italian and Slovenian). Consorzio Universitario del Friuli. St. Petersburg Branch of the Archive of the Russian Academy of Science. Inštitut za slovenski jezik Frana Ramovša, Znanstvenoraziskovalni center Slovenske akademije znanosti in umetnosti. ISBN 978-961-254-142-2.

Bibliography[edit]

- Ježovnik, Janoš (2019). Notranja glasovna in naglasna členjenost terskega narečja slovenščine (in Slovenian). Ljubljana. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- Šekli, Matej (2018). Legan Ravnikar, Andreja (ed.). Tipologija lingvogenez slovanskih jezikov (in Slovenian). Translated by Plotnikova, Anastasija. Ljubljana: Znanstvenoraziskovalni center SAZU. ISBN 978-961-05-0137-4.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)