User:HeidiCI26/Scramble (slave auction)

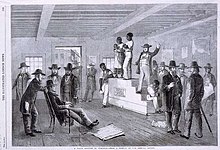

A scramble was a particular form of slave auction that took place during the Atlantic slave trade in the European colonies of the West Indies and the United States. It was called a "scramble" because buyers would run around in an open space all at once to gather as many bondspeople[1] as possible. Another name for a scramble auction is "Grab and go" slave auctions. Slave ship captains would go to great lengths to prepare their captives and set prices for these auctions to make sure they would receive the highest amount of profits possible because it usually did not involve earlier negotiations or bidding.

History[edit]

The Scramble was first done as a form of slave auctioning in the West Indies. During the late eighteenth century, the term "scramble" was coined from the practices of slave auctions in the West Indies and the Caribbean. The scramble would take place on a ship, in a pen, or an enclosed area. The reason captain's selling their captives in a form of an enclosed area was to prevent a revolt against the ship crew and/or to quickly sell off the enslaved.[2] Once bondspeople were docked and brought onto land they would be herded into a pen, the ship, or an enclosed area, surrounded by eager buyers, often pushing and shoving to position themselves to the front of the pen's doors. The scramble was started by signal, either a gunshot or a drum beat, and once this was heard, the buyers swarmed into the pen to collect as many individuals as they could.[3] During the scramble fights often broke out among the buyers, which will be discussed more under the topic "First Hand Accounts of the Sramble".[4] Olaudah Equiano, an African captive who was able to gain freedom, describes the scramble as starting from a signal, the beat of a drum, and then the buyers rushed into the yard, where Equiano and the other bondspeople were kept, to grab the enslaved peoples they liked best.[5]

Anna Maria Falconbridge and Alexander Falconbridge were a married couple from London who lived during the 18th Century. Anna Maria was the first English woman to publish an eyewitness account of her experiences in West Africa with her husband, a previous surgeon on a slave ship turned abolitionist. Anna Maria’s writing of the two voyages were used in the campaign to abolish the Atlantic Slave Trade. Ironically, she defended the slave trade in her own narrative called the Two Voyages to the River Sierra Leone during the Years 1791–1792–1793. Specifically relating to the type of slave auction called the scramble, Christopher Fyfe, a historian who specializes in West Africa, gives a description of it from Anna Maria Falconbridge’s perspective.[6] Do note that this perspective is from an English woman who defended the slave trade. The scrambles witnessed were in Jamaica, one in Kingston, and the other in Port Maria. For the scramble in Kingston, the slaves were all collected upon the main and quarter deck of the ship where it was darkened (in order to prevent potential buyers from clearly seeing the slaves). Once the signal was given for the scramble to commence, the buyers rushed in.[6] Slaves were so terrified that almost thirty of them jumped ship. The scramble in Port Maria was conducted similarly to the one in Kingston. Only this time, the situation of the slaves was more described.[6] Fyfe describes the women as being terrified, clinging to one another in protection, and in great agony. The buyers are described as savages because of the brutal way they rushed on the slaves to grab and eventually purchase them.[6]

Preparation[edit]

Commonalities of Prepping the Enslaved[edit]

The enslaved were "prepared" for the auction by "experts", surgeons, or the common crewmen. Before the enslaved were examined as individuals, the crewmen would strip them down, and herd them together in a small open space so the surgeons could examine their health and youthfulness.[7] The captains, surgeons, or crew members would wash the enslaved men, women, and children, usually with sea water, and shave the adults to get rid of grey hair in hopes they would look younger.[8] The major problem crewmen had to tackle was to create the illusion that the enslaved peoples were healthy. One way crewmen were able to do this was to give bondspeople rum so their eyes would seem alive as well as slathering them in oil or animal fat to accentuate their muscles. There are even reports of the "experts" and crewmen fixing up the enslaved wounds with gunpowder and/or iron rust, and their anuses would be closed to stop leakage with a makeshift cork.[9] Palm oil, aside from gunpowder or iron rust, was also rubbed on the captives to cover up their bruises, sores, and cuts.[8] Branding the enslaved peoples of which European nation and/or their respective owner was also common, men would be burned on the arms, and women on the breasts.[7] All of these techniques were used to ensure that the captains would make the highest profits possible. In the morning of a scramble slave auction, buyers were able to come early to inspect the captives themselves, but there were not any possibilities of private sales or negotiations;[10] buyers would examine the bondspeople by opening their mouths to see their teeth, touching their arms and legs to feel how muscular they were, making them walk to see any "lameness", and making them bend in a variety of ways so buyers could see any wounds that were possibly masked by oil, animal fat, iron rust, etc.[10]

"Seasoning"[edit]

Another way the preparation aspect is defined, is by "seasoning". The seasoning of slaves was a period of adjustment where merchants and traders conditioned enslaved peoples so they could get used to their new life on plantations.[11] The process of seasoning is seen as a way to break the African captives by taking away their identity, so they would be less likely to revolt and get their work done on or off the plantation.[11] In order for the bondspeople to be conditioned correctly traders and merchants would "Creolize" (the act of changing the attitudes of an African-born captive into an American-born bondsperson) by shaving off all of their hair, washing them, oil them down, and then feed them very little.[11] The last part of "Creolizing" an African captive dealt with sending enslaved peoples to the West Indies before being sold in the American South so they knew what it was like to work on plantations.[11] Other forms of seasoning included branding the enslaved with the mark of their new owner, renaming the enslaved in order to strip them from their African identity, and torturing them.[11] During these processes women in particular were subjected to many harsh and unwanted sexual acts that were advanced by the white merchants, and sometimes captive African men.[11]

Women's Experiences[edit]

The accounts of enslaved peoples are already difficult to find within historical research and recordings. The stories of women are even more difficult to account for in terms of their point of view within a scramble sale. We must rely on the fact that slaves were selected upon the surface level set of appearance that buyers were presented and the accounts primarily of those buyers. As well as the accounts of others, such as John Josselyn, an English traveler that reported what he saw on his voyages. When Josselyn headed to New England he was provided lodging at Samuel Maverick’s home. Maverick was one of the first slave owners in Massachusetts and by 1638 he owned at least three slaves, two of them which were non-English speaking women. Both of these enslaved women are thought of being bought in a scramble, being sold for a lesser amount than the young men.[12]

One young girl, sixteen to seventeen years of age, was forced to show off her limbs and teeth by smiling to prospective buyers. While smiling one interested buyer moved her lips around so he could look at every crevasse up close.[13]

Female slaves were used as wet nurses for their white slave owners. They were also kept to produce more slaves resulting in cheap labor and generational servitude. In Stephanie Jones-Rogers' book They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South mentions many of these enslaved women's experiences, such as Mary Kincheon Edwards. Edward job was to nurse the white children was the only job Edwards had to perform while she was enslaved, which leads to believe that she and many other women who performed this task were constantly conceiving.[14]

First Hand Accounts of Scramble Auctions[edit]

In Olaudah Equiano's book The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, he mentions his experiences while being prepped for a scramble slave auction. While still on board, Equiano states that they were separated into different parcels, men and women, where they were "examined" by having to jump.[5] Once on land they were rounded up like sheep in the merchant's yard where they stayed for a few days until the scramble auction started by a beat of a drum. During the scramble, Equiano illustrates how inhumane buyers acted during this process. He states that the buyers visually seemed eager to get their hands on as many bondspeople as possible.[5]

Frederic Bancroft writes about a traveler's observation of a slave being examined in his book Slave Trading in the Old South[15]. The traveler recalls that the captive was forced to strip naked so buyers could see if there were any signs of damage from cuts, wounds, and/or bruising, and disease; he states that there was not any part of the captive's body that was untouched.[15]

John Tailyour, a ship captain that mostly sailed to Guinea, Africa, writes how he prepared for scramble slave auctions. Tailyour conducted scramble auctions in the years of 1782-1784, 1789, and 1792-1793, and each time he employed the same factors to ensure he would receive the highest profits.[16] Before going on land to the sale site Tailyour would separate his captives into two categories: "prime" and "refuse"; prime bondspeople were young men and women, ranging in the ages from the late teens to thirty, were in good health, and free of injuries, wounds, and sickness while "refuse" bondspeople were either very old or very young, sick, and/or covered with wounds.[16] On the day of the scramble, or a day before, Tailyour would then create ten different categories for the enslaved: "privilege men", "cargo men", "privilege men-boys", "men-boys", and the women being the same; based on these categories prices were set at two Jamaican pounds, with the "better quality" captives being two pounds more than the next, and each female category was priced two pounds lower than their male equivalent.[16] Tailyour created these separations because the "privilege slaves", weather male or female, were saved for his close friends and family, with the rest being put into the scramble. John Tailyour's "refuse slaves" were also put into scrambles, but were specifically for plantation owners who could not afford to pay for the other categories.[16]

Thomas Hibbert, an English merchant and plantation owner in Jamaica, discussed the possible dangers of a scramble that he witnessed to Nathaniel Phillips another plantation owner. Here, Hibbert stated, that he expected half of the buyers waiting at the gates to be trampled to death by the other half.[16]

Alexandre Lindo, a ship captain for two slave ships, records selling an entire ship of captives in four hours, which was the most amount of bondspeople sold until 1805 when thirty plantation owners bought an entire human cargo worth in one hour, both being sold by the scramble method.[17]

Alexander Falconbridge, husband of Anna Maria Falconbridge, who were both surgeons for four different voyages, recounts the scramble slave auction in his book, An Account of the Slave Trade on the Coast of Africa. He states that buyers would pay a fixed price for the captives that was negotiated among the ship's captains and the purchasers.[17] Falconbridge describes that as soon as the agreed start hour came around the doors of the yard, where the captives were held, were thrown open, and the buyers instantly ran in to gather bondspeople. Some buyers came prepared by bringing handkerchiefs or ropes so they could tie the slaves together without losing them while grabbing others.[17] Falconbridge calls the buyers "brutes" who had no form of sympathy for the captives; because of this, he recalls some of the enslaved to be so frightened that they would jump over the walls to escape.[17] On the ship Golden Age, Falconbridge records the selling of 503 captives in two days in December 1784 at Port Maria, Jamaica.[16]

External Links[edit]

- The Great Slave Auction

- Frederic Bancroft

- [1]

- Atlantic Slave Trade

- Seasoning

- Human branding

- Slavery

- Olaudah Equiano

- Alexander Falconbridge

- Anna Maria Falconbridge

- The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano

- Thomas Hibbert

- [2]

- Stephanie Jones-Rogers

- They Were Her Property

- John Josselyn

- Samuel Maverick (colonist)

- [3]

- [4]

- [5]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Sowande' M. Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea: Terror, Sex, and Sickness in the Middle Passage (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2016).

- ^ Shingirai Mutonho, "'Weeping Time' as Auctioned Kicked Off . . . The Scramble," The Patriot, July 18, 2019, https://www.thepatriot.co.zw/old_posts/weeping-time-as-auction-kicked-off-the-scramble/.

- ^ Richard Watkins, Slavery: Bondage Throughout History (Houghton Mifflin, 2001).

- ^ P.C. Emmer, The Dutch Slave Trade, 1500-1850 (Burghahn Books, 2006), 83.

- ^ a b c Olaudah Equiano, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano: (London: 1789).

- ^ a b c d Christopher Fyfe, "Sale of the Slaves" in Anna Maria Falconbridge (2017), 216.

- ^ a b Willem Bosman, "A New and Accurate Description," in The Atlantic Slave Trade, ed., David Northrup (Lexington, Mass.: Heath, 1994), 72-73.

- ^ a b "History of Slavery: The Americas," National Museums Liverpool, accessed 03/09/2021, https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/history-of-slavery/americas.

- ^ Kenneth F. Kiple, The Caribbean Slave: A Biological History (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1984), 57.

- ^ a b "Black Peoples of America - The Slave Auction", CUSD, accessed March 03, 2021, https://www.cusd80.com/cms/lib6/AZ01001175/Centricity/Domain/4844/Slavery%20Station%201.pdf.

- ^ a b c d e f Glenn Chambers, "The Transatlantic Slave Trade and Origins of African Diaspora in Texas," Prairie View A&M University, accessed April 08, 2021, https://www.pvamu.edu/tiphc/research-projects/the-diaspora-coming-to-texas/the-transatlantic-slave-trade-and-origins-of-the-african-diaspora-in-texas/.

- ^ Warren, Wendy Anne (2007-03-01). ""The Cause of Her Grief": The Rape of a Slave in Early New England". Journal of American History. 93 (4): 1031–1049. doi:10.2307/25094595. ISSN 0021-8723.

- ^ William Brennen, "Female Objects of Semantic Dehumanization and Violence," Studies in Prolife Feminism 1, no.3, (Summer 1995): 203+, GALE|A95922384.

- ^ Stephanie Jones-Rogers, They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2019).

- ^ a b Frederic Bancroft, Slave Trading in the Old South (Ungar, 1959).

- ^ a b c d e f Nicholas Radburn. "Guinea Factors, Slave Sales, and the Profits of the Transatlantic Slave Trade in Late Eighteenth-Century Jamaica: The Case of John Tailyour." The William and Mary Quarterly 72, no. 2 (April 2015): 269-274, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5309/willmaryquar.72.2.0243.

- ^ a b c d Alexander Falconbridge, "Disposal of Sick Slaves," in An Account of the Slave Trade on the Coast of Africa, edited by Steven Mintz, (London: 1789), http://www.vgskole.net/prosjekt/slavrute/9.htm.

Bibliography[edit]

Bancroft, Frederic. Slave Trading in the Old South. Ungar, 1959.

"Black Peoples of America - The Slave Auction". CUSD. accessed March 03, 2021. https://www.cusd80.com/cms/lib6/AZ01001175/Centricity/Domain/4844/Slavery%20Station%201.pdf.

Bosman, Williem. "A New and Accurate Description." in The Atlantic Slave Trade edited by David Northrup, 72-73. Lexington, Mass.: Heath, 1994.

Brennan, William. "Female Objects of Semantic Dehumanization and Violence." Studies in Prolife Feminism 1, no. 3 (Summer 1995). 203+. GALE|A95922384.

Chambers, Glenn. "The Transatlantic Slave Trade and Origins of African Diaspora in Texas." Prairie View A&M University. accessed April 08, 2021. https://www.pvamu.edu/tiphc/research-projects/the-diaspora-coming-to-texas/the-transatlantic-slave-trade-and-origins-of-the-african-diaspora-in-texas/.

Emmer, P.C., The Dutch Slave Trade. Berghahn Books, 2006.

Equiano, Olaudah. The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano. London: 1789.

Falconbridge, Alexander. "Disposal of Sick Slaves." in An Account of the Slave Trade on the Coast of Africa, edited by Steven Mintz. London: 1788. http://www.vgskole.net/prosjekt/slavrute/9.htm.

Fyfe, Christopher. "Sale of Slaves" in Anna Maria Falconbridge: 2017.

"History of Slavery: The Americas." National Liverpool Museums. accessed 03/09/2021. https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/history-of-slavery/americas.

Jones-Rogers, Stephanie. They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2019.

Kiple, Kenneth F. The Caribbean Slave: A Biological History. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

Mustakeem, Sowande' M. Slavery at Sea: Terror, Sex, and Sickness in the Middle Passage. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2016.

Mutonhon, Shingirai. "'Weeping Time' as Auction Kicked Off . . . the Scramble". The Patriot. July 18, 2019. https://www.thepatriot.co.zw/old_posts/weeping-time-as-auction-kicked-off-the-scramble/.

Radburn, Nicholas. "Guinea Factors, Slave Sales, and the Profits of the Transatlantic Slave Trade in Late Eighteenth-Century Jamaica: The Case of John Tailyour." The William and Mary Quarterly 72, no. 2 (April 2015).

Warren, Wendy Anne. “The Cause of Her Grief: The Rape of a Slave in Early New England.” The Journal of American History 93, no. 4 (March 2007): 1031–49. https://doi.org/10.2307/25094595.

Watkins, Richard. Slavery: Bondage Throughout History. Houghton Mifflin, 2001.