User:Hires an editor/CWSandbox

"Containment" through the Korean War (1947–53)[edit]

By 1947, US president Harry S. Truman's advisors were worried that time was running out to counter the influence of the Soviet Union, as Stalin was seeking to weaken the position of the US in the period of post-war confusion and collapse by encouraging rivalries among capitalists in order to bring about a new war.[1] In Asia, the Red Army had overrun Manchuria in the last month of the war and then also occupied Korea above the 38th parallel north. Mao Zedong's Communist Party of China, though receptive to minimal Soviet support, defeated the pro-Western and heavily American-assisted Chinese Nationalist Party in the Chinese Civil War.

Europe[edit]

All kinds of things were happening in Europe. The US had a three pronged strategy for dealing with the perceived economic, political, and military threat from the Soviet Union, and from communists coming to power in European countries. The Marshall Plan, Containment, and NATO.

The Soviets, for their part, were setting up puppet governments in Eastern Europe.

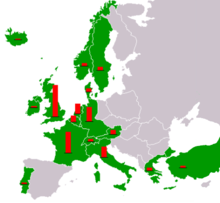

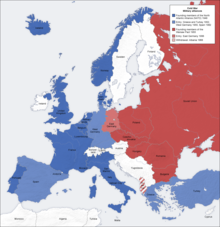

The USSR was setting up puppet communist regimes in Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and East Germany, as the Red Army maintained a military presence in most of these countries.[2] In February 1947, the British government announced that it could no longer afford to finance the Greek monarchical military regime in its civil war against communist-led insurgents. The American government's response to this announcement was the adoption of "containment",[3] whose goal was to stop the spread of communism. Truman gave a speech to unveil the "Truman Doctrine", which painted the conflict as a contest between "free" peoples and "totalitarian" regimes. Even though the insurgents were helped by Josip Broz Tito's Yugoslavia,[4] US policymakers accused the Soviet Union of conspiracy against the Greek royalists in an effort to "expand" their influence.[5]

For US policymakers, threats to Europe's balance of power were not necessarily military ones, but a political and economic challenge.[2] In June, the Truman Doctrine was complemented by the Marshall Plan, a pledge of economic assistance aimed at rebuilding the Western political-economic system and countering perceived threats to Europe's balance of power, such as communist parties attempting to seize power through free elections or popular revolutions, in countries like France or Italy.[6] Stalin saw the Plan as a significant threat to Soviet control of Eastern Europe and believed that economic integration with the West would allow Eastern Bloc countries to escape Soviet guidance, and that the US was trying to "buy" a pro-US re-alignment of Europe. Stalin therefore prevented Eastern Bloc nations from receiving Marshall Plan aid. The Soviet Union's "alternative" to the Marshall plan, which was purported to involve Soviet subsidies and trade with western Europe, became known as the Molotov Plan, and later, the COMECON.[4] Stalin was also fearful of a reconstituted Germany, as his vision of a post-war Germany did not include the ability to rearm, or be any kind of a threat to the Soviet Union.

In retaliation for Western efforts to re-industrialize and rebuild the German economy, Stalin built blockades which prevented Western materials and supplies from getting to West Berlin. This became known as the Berlin Blockade, and was one of the first major crises of the Cold War. Both sides used propaganda against each other, with the Soviets mounting a public relations campaign against the US policy change, and the US accidentally creating "Operation Little Vittles", which gave candy to German children. The Berlin Blockade ended peacefully, with Stalin backing down, and allowing normal shipments to resume back to West Berlin.

In July, Truman rescinded the punitive Morgenthau plan (part of an agreement with the Soviet Union regarding post-war Germany), which had specifically directed US occupation forces in Germany not to assist in Germany's economic rehabilitation efforts. It was replaced by a new directive which stressed instead that European prosperity was contingent upon German economic recovery.[7]

In September, the Soviets created Cominform whose purpose was to tighten political control over Soviet satellites through coordination of communist parties in the Eastern Bloc. Cominform faced an embarrassing setback the following June, when the Tito-Stalin split obliged them to expel Yugoslavia, which remained Communist but adopted a neutral stance in the Cold War.[8]

As part of Soviet domination of Eastern Europe, the NKVD, led by Lavrentiy Beria, supervised the establishment of Soviet-style systems of secret police in the Eastern European states, which were supposed to crush anti-communist resistance.[9] When the slightest stirrings of independence emerged among East European satellites, Stalin's strategy was to deal with those responsible in the same manner he had handled his prewar rivals within the Soviet Union: they were removed from power, put on trial, imprisoned, and in several instances, executed.[10]

The US formally allied itself to the Western European states in the North Atlantic Treaty of April 1949, establishing the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).[11] That August, Stalin ordered the detonation of the first Soviet atomic device.[4]

Additionally, the US spearheaded the establishment of West Germany from the three Western zones of occupation in May 1949.[12] To counter this Western reorganisation of Germany, the Soviet Union proclaimed its zone of occupation in Germany the "German Democratic Republic" that October.[12] In the early 1950s, the US worked for the rearmament of West Germany and, in 1955, its full membership to NATO.[12] In May 1953, Lavrentiy Beria, appointed First Deputy Prime Minister of the Soviet Union, made an unsuccessful proposal to allow the reunification of a neutral Germany to prevent West Germany's incorporation into NATO.[13]

Asia[edit]

In 1949, Mao's Red Army defeated the US-backed Kuomintang regime in China. The Soviet Union created an alliance with the newly formed People's Republic of China.[14] Confronted with the Chinese Revolution and the end of the US atomic monopoly in 1949, the Truman administration quickly moved to escalate and expand the containment policy.[4] In a secret 1950 document,[15] Truman administration officials proposed to reinforce pro-Western alliance systems and quadruple spending on defence.[4]

US officials moved thereafter to expand "containment" into Asia, Africa, and Latin America, in order to counter revolutionary nationalist movements, often led by Communist parties financed by the USSR, fighting against the restoration of Europe's colonial empires in South-East Asia.[16] In the early 1950s, The US formalized a series of alliances with Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Thailand and the Philippines (notably ANZUS and SEATO), thereby guaranteeing the United States a number of long-term military bases.[12]

One of the more significant impacts of containment was the Korean War. As noted, the US and the Soviet Union had been fighting proxy wars, on a small scale, and without US troops; but to Stalin's surprise, Truman committed US forces to drive back the North Koreans, who had invaded South Korea;[4] this action was backed by the UN Security Council only because the Soviets were then boycotting meetings in protest that Taiwan and not Communist China held a permanent seat there.[17]

Among other effects, the Korean War galvanised NATO to develop a military structure,[18] as all communist countries were suspected of acting together. Public opinion in countries such as Great Britain, usual allies of the US, was divided for and against the war. British Attorney General Sir Hartley Shawcross repudiated the sentiment of those opposed when he said:

- "I know there are some who think that the horror and devastation of a world war now would be so frightful, whoever won, and the damage to civilization so lasting, that it would be better to submit to Communist domination. I understand that view – but I reject it".[19]

Even if the Chinese and North Koreans were exhausted by the war and were ready to end it by late 1952, Stalin insisted that they should continue fighting, and a cease-fire was approved only in July 1953, after Stalin's death.[12]

- ^ Gaddis 2005, p. 27

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Schmitzwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Gaddis 2005, pp. 28–29

- ^ a b c d e f Cite error: The named reference

LaFeber 1991was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Gaddis 2005, p. 38

- ^ Gaddis 1990, p. 186

- ^ "Pas de Pagaille!". Time magazine. July 28, 1947. Retrieved 2008-05-28.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Carabott, p. 66

- ^ Gaddis 2005, p. 34

- ^ Gaddis, p. 100

- ^ Gaddis 2005, p. 34

- ^ a b c d e Cite error: The named reference

Byrdwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Gaddis 2005, p. 105

- ^ Gaddis 2005, p. 39

- ^ Gaddis 2005, p. 164

- ^ Gaddis 2005, p. 212

- ^ Malkasian, p. 16

- ^ Isby, pp. 13–14

- ^ Column by Ernest Borneman, Harper's Magazine, May 1951