User:It's gonna be awesome/amphetamines-related

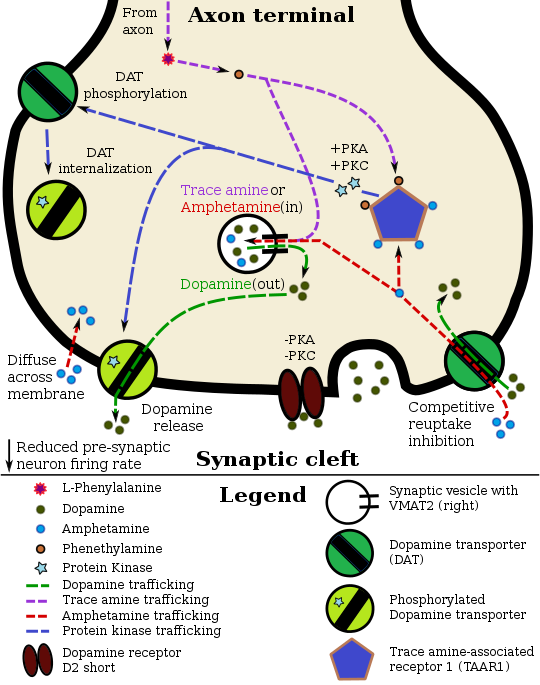

Pharmacodynamics of amphetamine in a dopamine neuron

|

Translation starts from here:

- Dopamine = 多巴胺

- Axon terminal = 軸突末端

- Amphetamine = 安非他命

- Dopamine release = 多巴胺釋放

- Dopamine (out) 多巴胺 (出)

- Trace amine or amphetamine (in) : 痕量胺 或 安非他命 (進)

Second paragraph[edit]

Translation starts from here:

- Dopamine = 多巴胺

- Synaptic cleft =突觸間隙

- ^ a b c d e Miller GM (January 2011). "The emerging role of trace amine-associated receptor 1 in the functional regulation of monoamine transporters and dopaminergic activity". J. Neurochem. 116 (2): 164–176. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x. PMC 3005101. PMID 21073468.

- ^ a b Eiden LE, Weihe E (January 2011). "VMAT2: a dynamic regulator of brain monoaminergic neuronal function interacting with drugs of abuse". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1216 (1): 86–98. Bibcode:2011NYASA1216...86E. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05906.x. PMC 4183197. PMID 21272013.

VMAT2 is the CNS vesicular transporter for not only the biogenic amines DA, NE, EPI, 5-HT, and HIS, but likely also for the trace amines TYR, PEA, and thyronamine (THYR) ... [Trace aminergic] neurons in mammalian CNS would be identifiable as neurons expressing VMAT2 for storage, and the biosynthetic enzyme aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (AADC). ... AMPH release of DA from synapses requires both an action at VMAT2 to release DA to the cytoplasm and a concerted release of DA from the cytoplasm via "reverse transport" through DAT.

- ^ Sulzer D, Cragg SJ, Rice ME (August 2016). "Striatal dopamine neurotransmission: regulation of release and uptake". Basal Ganglia. 6 (3): 123–148. doi:10.1016/j.baga.2016.02.001. PMC 4850498. PMID 27141430.

Despite the challenges in determining synaptic vesicle pH, the proton gradient across the vesicle membrane is of fundamental importance for its function. Exposure of isolated catecholamine vesicles to protonophores collapses the pH gradient and rapidly redistributes transmitter from inside to outside the vesicle. ... Amphetamine and its derivatives like methamphetamine are weak base compounds that are the only widely used class of drugs known to elicit transmitter release by a non-exocytic mechanism. As substrates for both DAT and VMAT, amphetamines can be taken up to the cytosol and then sequestered in vesicles, where they act to collapse the vesicular pH gradient.

- ^ Ledonne A, Berretta N, Davoli A, Rizzo GR, Bernardi G, Mercuri NB (July 2011). "Electrophysiological effects of trace amines on mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons". Front. Syst. Neurosci. 5: 56. doi:10.3389/fnsys.2011.00056. PMC 3131148. PMID 21772817.

Three important new aspects of TAs action have recently emerged: (a) inhibition of firing due to increased release of dopamine; (b) reduction of D2 and GABAB receptor-mediated inhibitory responses (excitatory effects due to disinhibition); and (c) a direct TA1 receptor-mediated activation of GIRK channels which produce cell membrane hyperpolarization.

- ^ "TAAR1". GenAtlas. University of Paris. 28 January 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

• tonically activates inwardly rectifying K(+) channels, which reduces the basal firing frequency of dopamine (DA) neurons of the ventral tegmental area (VTA)

- ^ Underhill SM, Wheeler DS, Li M, Watts SD, Ingram SL, Amara SG (July 2014). "Amphetamine modulates excitatory neurotransmission through endocytosis of the glutamate transporter EAAT3 in dopamine neurons". Neuron. 83 (2): 404–416. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2014.05.043. PMC 4159050. PMID 25033183.

AMPH also increases intracellular calcium (Gnegy et al., 2004) that is associated with calmodulin/CamKII activation (Wei et al., 2007) and modulation and trafficking of the DAT (Fog et al., 2006; Sakrikar et al., 2012). ... For example, AMPH increases extracellular glutamate in various brain regions including the striatum, VTA and NAc (Del Arco et al., 1999; Kim et al., 1981; Mora and Porras, 1993; Xue et al., 1996), but it has not been established whether this change can be explained by increased synaptic release or by reduced clearance of glutamate. ... DHK-sensitive, EAAT2 uptake was not altered by AMPH (Figure 1A). The remaining glutamate transport in these midbrain cultures is likely mediated by EAAT3 and this component was significantly decreased by AMPH

- ^ Vaughan RA, Foster JD (September 2013). "Mechanisms of dopamine transporter regulation in normal and disease states". Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 34 (9): 489–496. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2013.07.005. PMC 3831354. PMID 23968642.

AMPH and METH also stimulate DA efflux, which is thought to be a crucial element in their addictive properties [80], although the mechanisms do not appear to be identical for each drug [81]. These processes are PKCβ– and CaMK–dependent [72, 82], and PKCβ knock-out mice display decreased AMPH-induced efflux that correlates with reduced AMPH-induced locomotion [72].

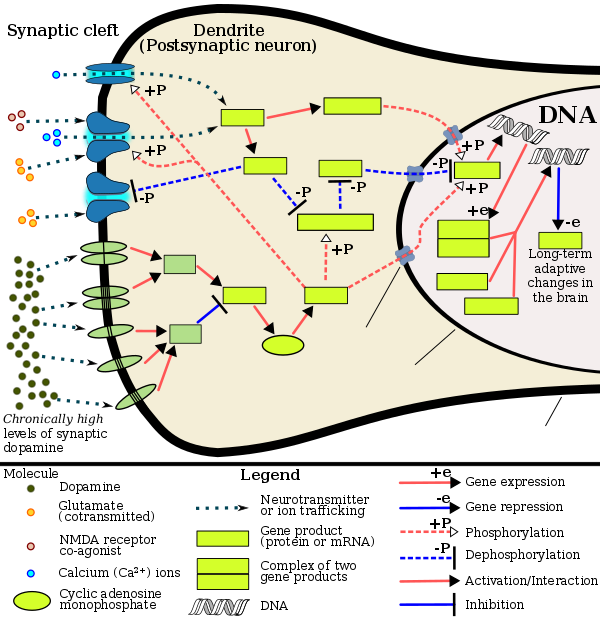

- ^ a b c Renthal W, Nestler EJ (September 2009). "Chromatin regulation in drug addiction and depression". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 11 (3): 257–268. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.3/wrenthal. PMC 2834246. PMID 19877494.

[Psychostimulants] increase cAMP levels in striatum, which activates protein kinase A (PKA) and leads to phosphorylation of its targets. This includes the cAMP response element binding protein (CREB), the phosphorylation of which induces its association with the histone acetyltransferase, CREB binding protein (CBP) to acetylate histones and facilitate gene activation. This is known to occur on many genes including fosB and c-fos in response to psychostimulant exposure. ΔFosB is also upregulated by chronic psychostimulant treatments, and is known to activate certain genes (eg, cdk5) and repress others (eg, c-fos) where it recruits HDAC1 as a corepressor. ... Chronic exposure to psychostimulants increases glutamatergic [signaling] from the prefrontal cortex to the NAc. Glutamatergic signaling elevates Ca2+ levels in NAc postsynaptic elements where it activates CaMK (calcium/calmodulin protein kinases) signaling, which, in addition to phosphorylating CREB, also phosphorylates HDAC5.

Figure 2: Psychostimulant-induced signaling events - ^ Broussard JI (January 2012). "Co-transmission of dopamine and glutamate". The Journal of General Physiology. 139 (1): 93–96. doi:10.1085/jgp.201110659. PMC 3250102. PMID 22200950.

Coincident and convergent input often induces plasticity on a postsynaptic neuron. The NAc integrates processed information about the environment from basolateral amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex (PFC), as well as projections from midbrain dopamine neurons. Previous studies have demonstrated how dopamine modulates this integrative process. For example, high frequency stimulation potentiates hippocampal inputs to the NAc while simultaneously depressing PFC synapses (Goto and Grace, 2005). The converse was also shown to be true; stimulation at PFC potentiates PFC–NAc synapses but depresses hippocampal–NAc synapses. In light of the new functional evidence of midbrain dopamine/glutamate co-transmission (references above), new experiments of NAc function will have to test whether midbrain glutamatergic inputs bias or filter either limbic or cortical inputs to guide goal-directed behavior.

- ^ Kanehisa Laboratories (10 October 2014). "Amphetamine – Homo sapiens (human)". KEGG Pathway. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

Most addictive drugs increase extracellular concentrations of dopamine (DA) in nucleus accumbens (NAc) and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), projection areas of mesocorticolimbic DA neurons and key components of the "brain reward circuit". Amphetamine achieves this elevation in extracellular levels of DA by promoting efflux from synaptic terminals. ... Chronic exposure to amphetamine induces a unique transcription factor delta FosB, which plays an essential role in long-term adaptive changes in the brain.

- ^ Cadet JL, Brannock C, Jayanthi S, Krasnova IN (2015). "Transcriptional and epigenetic substrates of methamphetamine addiction and withdrawal: evidence from a long-access self-administration model in the rat". Molecular Neurobiology. 51 (2): 696–717 (Figure 1). doi:10.1007/s12035-014-8776-8. PMC 4359351. PMID 24939695.

- ^ a b c Robison AJ, Nestler EJ (November 2011). "Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of addiction". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 12 (11): 623–637. doi:10.1038/nrn3111. PMC 3272277. PMID 21989194.

ΔFosB serves as one of the master control proteins governing this structural plasticity. ... ΔFosB also represses G9a expression, leading to reduced repressive histone methylation at the cdk5 gene. The net result is gene activation and increased CDK5 expression. ... In contrast, ΔFosB binds to the c-fos gene and recruits several co-repressors, including HDAC1 (histone deacetylase 1) and SIRT 1 (sirtuin 1). ... The net result is c-fos gene repression.

Figure 4: Epigenetic basis of drug regulation of gene expression - ^ a b c Nestler EJ (December 2012). "Transcriptional mechanisms of drug addiction". Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience. 10 (3): 136–143. doi:10.9758/cpn.2012.10.3.136. PMC 3569166. PMID 23430970.

The 35-37 kD ΔFosB isoforms accumulate with chronic drug exposure due to their extraordinarily long half-lives. ... As a result of its stability, the ΔFosB protein persists in neurons for at least several weeks after cessation of drug exposure. ... ΔFosB overexpression in nucleus accumbens induces NFκB ... In contrast, the ability of ΔFosB to repress the c-Fos gene occurs in concert with the recruitment of a histone deacetylase and presumably several other repressive proteins such as a repressive histone methyltransferase

- ^ Nestler EJ (October 2008). "Transcriptional mechanisms of addiction: Role of ΔFosB". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 363 (1507): 3245–3255. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0067. PMC 2607320. PMID 18640924.

Recent evidence has shown that ΔFosB also represses the c-fos gene that helps create the molecular switch—from the induction of several short-lived Fos family proteins after acute drug exposure to the predominant accumulation of ΔFosB after chronic drug exposure

Cite error: There are <ref group=Color legend> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=Color legend}} template (see the help page).