User:Jaelienrivera/Davenport Tablets

| This is not a Wikipedia article: It is an individual user's work-in-progress page, and may be incomplete and/or unreliable. For guidance on developing this draft, see Wikipedia:So you made a userspace draft. Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL |

Lead[edit]

The Davenport Tablets are three inscribed slate tablets that were found in mounds near Davenport, Iowa on January 10, 1877 and January 30, 1878. If these tablets were real, they would prove the theory that Native American mounds were built by an ancient race of settlers.[1] The Davenport Tablets were proven to be fake.

The first tablet was found in an in-tact mound next to three human skeletons with the bones scattered, but the last two were found in an area with loose soil.[2] One tablet represents a cremation scene, the second represents a hunting scene and the last a calendar.[3] The tablets had a total of 74 letters, deducting 24 repetitions.[4] However, the letters were in a random order that could not be properly interpreted. [2]

As the tablets were being examined, people questioned their authenticity. Dr. E Foreman, a member of the committee at The Davenport Academy, was working with the tablets and he had noticed that the engravings on the tablets were used with modern tools and they were in decent condition, which they should not have been if they were underground for as long as they should have been. The site where the tablets were found revealed that someone had dug and placed the tablets there because if the tablets remained untouched for many years, then the soil would have solidified by then rather than loose. [2]

Discovery[edit]

The first two tablets were discovered on January 10, 1877 by a local clergyman, the Reverend Jacob Gass, while engaged in an emergency excavation (due to the imminent transfer of the access rights) at the site known as Cook's Farm. They were found in one of the mounds on the site, Mound No. 3.[1] In an excavation on January 30, 1878 (the access rights having been restored), Charles Harrison, the president of the Davenport Academy of Natural Sciences, while excavating there with Gass, found a third tablet in Mound No. 11, which was nearby the mound where they had discovered the two previous tablets.[1] They are often associated in discussions with a pipe found by Gass and another Lutheran minister, the Reverend Ad Blumer in 1880 in a separate group of mounds, referred to as the 'elephant pipe' by Gass. Blumer gave the pipe to the Academy and shortly after his donation, the Academy acquired a similar pipe from Gass which he reported had been found by a farmer in Louisa County, Iowa. Charles Putnam, president and lawyer of The Davenport Academy, wrote a vindication of the artifacts in 1885.[5]

Mound No. 3[edit]

Grave A[edit]

As Gass continued digging in Mound No. 3, he had come across three human skeletons- two adults and one child, five copper axes wrapped in cloth, and copper beads. The child skeleton was found in between the two others 5 1/2 feet below the surface.[6] Above the skeletons lied a thick layer of shells and a sloping layer of shells. Two years before the discovery of the tablets, Dr. Farquharson said that "there were no layers of stones nor shells" in the mounds before.[6]

Grave B[edit]

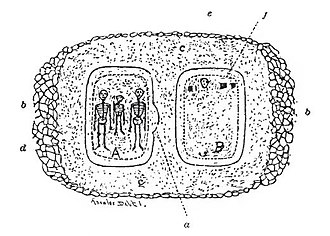

The first two tablets were found in Grave B. Mounds are typically constructed in layers, however the arch in this grave indicated that, at some point, the mound was disrupted. In the middle of the grave was a layer of stones. The grave is 6 feet wide and 10 feet long and dug about 2.5 feet in depth. This information alone revealed how easy it was to be able to place the tablets at the bottom, even without putting any of the other articles in the grave out of place.[6]

After the discovery of the tablets, Gass came back and removed some remaining articles in the grave such as scattered skeleton parts, a copper axe, copper beads, pottery fragments, and yellow pigment. Dr. Farquharson examined the tablets and noticed that the tablets did not weather much due to their original smoothing marks.[6]

Mound No.11[edit]

While the owners of Cooks' Farm were plowing, unusual stones were found and Gass visited the mounds again. During this excavation he discovered more stones with ancient engravings along with the last tablet. On May 15 he found five inscribed stones, two of which are in a museum and the other three were too large to remove.[6]

Debunking the Tablets[edit]

The Davenport Tablets were sent to the Bureau of American Ethnology in the Smithsonian Institute to be studied further. From 1877 to 1885, the experts announced the Davenport Tablets were frauds.[7] Initially, the authenticity of the Davenport artifacts was not questioned, and even received good reviews from people like Spencer Baird, of the Smithsonian Institution, and businessman Charles E. Putnam. However, a debate escalated between those at The Davenport Academy and the Smithsonian Institution regarding whether the Davenport Tablets were real or fake. From the pages of minor scholarly journals to the foremost news in the journal Science, eventually the tablets’ authenticity fell under the criticism of the new Smithsonian spokesman, Cyrus Thomas. Thomas lambasted them as “anomalous waifs,” that had absolutely no supporting, or contextual, evidence to aide in their authenticity.[8]

Interpretations[edit]

University of Iowa Professor, Marshall McKusick, now refers to the find and the circumstances surrounding it as “The Davenport Conspiracy”. McKusick suggested that the tablets were modified roof tiles stolen off the Old Slate House, a house of prostitutes,[9] even though Gass described finding them in a burial mound on the Cook family farm.

In his 1991 book, The Davenport Conspiracy Revisited, Professor Marshall McKusick asserts that Gass may have been the victim of an ill-advised joke played on him by fellow Davenport Academy members, who were possibly motivated by their jealousy of a foreign-born outsider in their midst. In 1874 Gass had made important discoveries of beautiful and complex Native American art at the Cook farm, such as copper axes. The level of technical ability and artistic craftsmanship by ancient Native Americans was evident in these artifacts. At a time when people digging along the Mississippi River in Iowa and Illinois were turning up nothing, Gass had the luck of hitting a genuine archaeological jackpot. After that date it is questionable as to what the motives of his academic rivals and relatives were.

Another explanation for the dubious origins of the artifacts might involve the credibility of Gass himself. It is believed that Gass dealt in fake Native American effigy pipes, such as the many examples illustrated in The Davenport Conspiracy Revisited. Genuine effigy pipes are a testament to the creative abilities of the ancient Native American Indians, but their counterfeits are of poor quality. Made of shale, clay, and limestone, these frauds were often traded amongst Gass and his colleagues, many ending up in the Davenport Academy museum. However, it is possible that Gass himself was not the perpetrator of these fakes, but was again under the influence of people who were jealous of his abilities and luck in selecting excavation sites. This time though, it was his own relatives, Edwin Gass and Adolph Blumer that persuaded him to take these fakes seriously and trade them.[8]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Putnam, Charles Edwin (1885). A Vindication of the Authenticity of the Elephant Pipes and Inscribed Tablets in the Museum of the Davenport Academy of Natural Sciences: From the Accusations of the Bureau of Ethnology, of the Smithsonian Institution. Glass & Hoover, printers.

- ^ a b c "The Davenport Conspiracy". phrontistery.info. Retrieved 2022-03-23.

- ^ "Preview unavailable - ProQuest". www.proquest.com. Retrieved 2022-03-23.

- ^ "THE DAVENPORT TABLETS - ProQuest". www.proquest.com. Retrieved 2022-03-23.

- ^ Putnam, Charles (1885). A Vindication Of The Authenticity Of The Elephant Pipes And Inscribed Tablets In The Museum Of The Davenport Academy Of Natural Sciences, 1885. ISBN ISBN 0-548-61492-X.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ a b c d e The American Antiquarian and Oriental Journal. Jameson & Morse. 1886.

- ^ "Why Piltdown and Not the Davenport Tablets?". phrontistery.info. Retrieved 2022-04-26.

- ^ a b McKusick, Marshall Bassford (1991). The Davenport conspiracy revisited. Marshall Bassford McKusick (1st ed ed.). Ames: Iowa State University Press. ISBN 0-8138-0344-6. OCLC 21908597.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Pinsky, Randy. "The Davenport Conspiracy: Revisited and Revised". Pseudoarchaeology. Retrieved 2 December 2017.