User:Kathleenem/sandbox

{{multiple issues|essay-like =September 2012|original research =September 2012}}

| John H. Watson | |

|---|---|

| Sherlock Holmes character | |

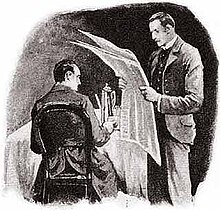

Dr. Watson (left) and Sherlock Holmes, by Sidney Paget. | |

| First appearance | A Study in Scarlet |

| Last appearance | "His Last Bow" |

| Created by | Sir Arthur Conan Doyle |

| In-universe information | |

| Gender | Male |

| Title | Doctor |

| Occupation | Physician |

| Spouse | Mary Morstan (wife) |

| Nationality | British |

John H. Watson, M.D., known as Dr. Watson, is a character in the Sherlock Holmes stories by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Watson is Sherlock Holmes's friend, assistant and sometime flatmate, and he is the first person narrator[1] of all but four stories in the Sherlock Holmes canon.

Background and description[edit]

Name[edit]

Doctor Watson's first name is mentioned on only three occasions. Part one of the very first Sherlock Holmes story, A Study in Scarlet, is subtitled 'Being a reprint from the Reminiscences of John H. Watson, M.D., Late of the Army Medical Department'.[2] In '"The Problem of Thor Bridge"', Watson says that his dispatch box is labeled 'John H. Watson, M.D'.[3] Watson's wife calls him 'James' in "The Man with the Twisted Lip"; Dorothy L. Sayers speculates that Morstan may be referring to his middle name Hamish (which means James in Scottish Gaelic), though Doyle himself never addresses this beyond including the initial.[4] In every other instance, his first name is never used again.

Character biography[edit]

In A Study in Scarlet, Watson, as the narrator, recounts his earlier life before meeting Holmes. It is established that Watson received his medical degree from the University of London in 1878, and had subsequently gone on to train at Netley as a surgeon in the British Army. He joined British forces in India, saw service in the Second Anglo-Afghan War, was wounded at the Battle of Maiwand, suffered enteric fever and was sent back to England on the troopship HMS Orontes following his recovery.[5]

In 1881, Watson runs into an old friend of his named Stamford, who tells him that an acquaintance of his, Sherlock Holmes, is looking for someone to split the rent at a flat in 221B Baker Street. Watson meets Holmes for the first time at a local hospital, where Holmes is conducting a scientific experiment. Holmes and Watson list their faults to each other to determine whether they can live together. The first of Watson's "confessions" is that he keeps a bull pup. Concluding that they are compatible, they subsequently move into the flat. When Watson notices multiple guests frequently visiting the flat, Holmes reveals that he is a "consulting detective" and that the guests are his clients.

By this time, Watson has already become impressed with Holmes' knowledge of chemistry and sensational literature. He witnesses Holmes' amazing skills at deduction as they embark on their first case together, concerning a series of murders related to Mormon intrigue. When the case is solved, Watson is angered that Holmes is not given any credit for it by the press. When Holmes refuses to record and publish his account of the adventure, Watson endeavours to do so himself. In time, Holmes and Watson become close friends.

In The Sign of the Four, John Watson becomes engaged to Mary Morstan, a governess. In "The Adventure of the Empty House", statements by Watson imply that Morstan has died by the time Holmes returns after faking his death; that fact is confirmed when Watson moves back to Baker Street to share lodgings with Holmes, as he had done as a bachelor. Conan Doyle made mention of a second wife in "The Adventure of the Illustrious Client" and "The Adventure of the Blanched Soldier", but this wife was never named, described, or explained. It was mentioned in His Last Bow that Watson was rejoining the service in London once more.

Physical appearance[edit]

In A Study in Scarlet, having just returned from Afghanistan, John Watson is described "as thin as a lath and as brown as a nut."[6] In subsequent texts, he is often described as strongly built, of a stature either average or slightly above average, with a thick, strong neck and a small moustache. Watson used to be an athlete: it is mentioned in "The Adventure of the Sussex Vampire" that he once played rugby for Blackheath, but he fears his physical condition has declined since that point.

Personal Characteristics[edit]

Skills and Personality[edit]

Watson is described as a crack shot [citation needed] and an excellent doctor and surgeon. Intelligent, if lacking in Holmes's insight, he serves as a perfect foil for Holmes: the archetypal late Victorian / Edwardian gentleman against the brilliant, emotionally-detached analytical machine.

Watson is well aware of both the limits of his abilities and Holmes's reliance on him:

"Holmes was a man of habits... and I had become one of them... a comrade... upon whose nerve he could place some reliance... a whetstone for his mind. I stimulated him... If I irritated him by a certain methodical slowness in my mentality, that irritation served only to make his own flame-like intuitions and impressions flash up the more vividly and swiftly. Such was my humble role in our alliance." – "The Adventure of the Creeping Man"

Watson is a capable and brave individual, whom Holmes does not hesitate to call upon for assistance: "Quickly Watson, get your service revolver!"[citation needed] Watson sometimes attempts to solve crimes on his own, using Holmes's methods. For example, in The Hound of the Baskervilles, Watson efficiently clears up several of the many mysteries confronting the pair, and Holmes praises him for his zeal and intelligence. However, because he is not endowed with Holmes's almost-superhuman ability to focus on the essential details of the case and Holmes's extraordinary range of recondite, specialised knowledge, Watson meets with limited success in other cases. Holmes summed up the problem that Watson confronted in one memorable rebuke from "A Scandal in Bohemia": "Quite so... you see, but you do not observe." In "The Adventure of the Solitary Cyclist," Watson's attempts to assist Holmes's investigation prove unsuccessful because of his unimaginative approach, for example, asking a London estate agent who lives in a particular country residence. (According to Holmes, what he should have done was "gone to the nearest public house" and listened to the gossip.) Watson is too guileless to be a proper detective. And yet, as Holmes acknowledges, Watson has unexpected depths about him; for example, he has a definite strain of "pawky humour", as Holmes observes in The Valley of Fear.

Watson never masters Holmes's deductive methods, but he can be astute enough to follow his friend's reasoning after the fact. In "The Adventure of the Norwood Builder," Holmes notes that John Hector McFarlane is "a bachelor, a solicitor, a Freemason, and an asthmatic". Watson comments as narrator: "Familiar as I was with my friend's methods, it was not difficult for me to follow his deductions, and to observe the untidiness of attire, the sheaf of legal papers, the watch-charm, and the breathing which had prompted them." Similar episodes occur in "The Adventure of the Devil's Foot," "The Adventure of the Solitary Cyclist," and "The Adventure of the Resident Patient." In "The Adventure of the Red Circle", we find a rare instance in which Watson rather than Holmes correctly deduces a fact of value. In The Hound of the Baskervilles[7] Watson shows that he has picked up some of Holmes's skills at dealing with people from whom information is desired. (As he observes to the reader, "I have not lived for years with Sherlock Holmes for nothing." )

Watson is endowed with a strong sense of honour. At the beginning of "The Adventure of the Veiled Lodger", Watson makes strong claims about "the discretion and high sense of professional honour" that govern his work as Holmes's biographer, but discretion and professional honour do not block Watson from expressing himself and quoting Holmes with remarkable candor on the characters of their antagonists and their clients. Despite Watson's frequent expressions of admiration and friendship for Holmes, the many stresses and strains of living and working with the detective make themselves evident in Watson's occasional harshness of character. The most controversial of these matters is Watson's candor about Holmes's drug use. Though the use of cocaine was legal in Holmes's era, Watson directly criticizes Holmes's habits.

Watson is also represented as being very discrete in character. The events related in “The Adventure of the Second Stain” are supposedly very sensitive: "If in telling the story I seem to be somewhat vague in certain details, the public will readily understand that there is an excellent reason for my reticence. It was, then, in a year, and even in a decade, that shall be nameless, that upon one Tuesday morning in autumn we found two visitors of European fame within the walls of our humble room in Baker Street." Furthermore, in "The Adventure of the Veiled Lodger," Watson notes that he has "made a slight change of name and place" when presenting that story. Here he is direct about a method of preserving discretion and confidentiality that other scholars have inferred from the stories, with pseudonyms replacing the "real" names of clients, witnesses, and culprits alike, and altered place-names replacing the real locations.

Additional Character History[edit]

Watson as Holmes's biographer[edit]

Throughout Doyle's novels, Watson is presented as Holmes's biographer. At the end of the first published Holmes story, A Study in Scarlet, Watson is so impressed by Holmes's handling of the case and so incensed by Scotland Yard's claiming full credit for its solution that he exclaims: "Your merits should be publicly recognised. You should publish an account of the case. If you won't, I will for you." Holmes suavely responds: "You may do what you like, Doctor." Hence Watson did write the story, presented as "a reprint from the reminiscences of John H. Watson".

In the first chapter of the second story that Watson records, The Sign of Four, Holmes comments on Watson's first effort as a biographer—but with a distinct lack of enthusiasm: "I glanced over it. Honestly, I cannot congratulate you upon it. Detection is, or ought to be, an exact science and should be treated in the same cold and unemotional manner. You have attempted to tinge it with romanticism... The only point in the case which deserved mention was the curious analytical reasoning from effects to causes, by which I succeeded in unravelling it." Watson admits, "I was annoyed at this criticism of a work which had been specially designed to please him. I confess, too, that I was irritated by the egotism which seemed to demand that every line of my pamphlet should be devoted to his own special doings." [citation needed]

Holmes sometimes accuses Watson of exaggerating his abilities. In "Silver Blaze", Holmes confesses: "I made a blunder, my dear Watson—which is, I am afraid, a more common occurrence than anyone would think who only knew me through your memoirs." When Holmes felt he had bungled something, he could exclaim: "Watson, Watson, if you are an honest man you will record this also and set it against my successes!" (The Hound of the Baskervilles, chapters 5–6.) In his prologue to "The Adventure of the Yellow Face," Watson himself remarked: "In publishing these short sketches [of Holmes’ cases]...it is only natural that I should dwell rather upon his successes than upon his failures", although he notes that this is also because where Holmes failed often nobody else succeeded.

Sometimes Watson (or rather Conan Doyle) seems determined to stop publishing stories about Holmes. In "The Adventure of the Second Stain", Watson declares that he had intended the previous story (“The Adventure of the Abbey Grange”) "to be the last of those exploits of my friend, Mr. Sherlock Holmes, which I should ever communicate to the public," but later Watson decided that "this long series of episodes should culminate in the most important international case which he has ever been called upon to handle" ("The Second Stain" being that case). Of course, the "long series of episodes" did not end with this story; there were some twenty stories yet to come.

Watson was able to cooperate with Holmes during seventeen of the twenty-three years the detective was in active practice, keeping "notes of his doings". Watson's published accounts are supposed to be based on these notes. [citation needed] In the later stories, written after Holmes's retirement (ca. 1903–04), Watson repeatedly refers to his notes about the various cases: "I have notes of many hundreds of cases to which I have never alluded.” He explained that after Holmes's retirement, the detective showed reluctance "to the continued publication of his experiences. So long as he was in actual professional practice the records of his successes were of some practical value to him, but since he has definitely retired...notoriety has become hateful to him" ("The Adventure of the Second Stain"). But during Holmes's active career, the publicity Watson gave to his cases was apparently good for business, however superficial Watson’s narratives may have seemed to the detective.

After Holmes's retirement, Watson often cites special permission from his friend for the publication of further stories. Yet he also received occasional unsolicited suggestions from Holmes about what stories to tell, as noted at the beginning of "The Adventure of the Devil's Foot". After receiving a telegram from Holmes, Watson promptly "hunt[ed] out the notes which give me the exact details of the case and to lay the narrative before my readers."

Origin[edit]

In Conan Doyle's early rough plot outlines, he intended the role of Watson to be filled by two junior detectives, Sandifer and Phillip[citation needed]; he later merged these characters as "Watson". In turn, Conan Doyle's introduction of Dr. Watson into the Holmes novels and stories proved a precursor to other, similar characters. Many of the great fictional detectives have their Watson: Agatha Christie's Hercule Poirot, for example, is accompanied by Captain Arthur Hastings; Rex Stout's Nero Wolfe had Archie Goodwin. J. R. R. Tolkien used the Hobbits in his works in a similar way, using characters such as Bilbo Baggins and Sam Gamgee to filter the intricate and mysterious aspects of his novels through to the audience.

- In the words of William L. De Andrea,

- "Watson also serves the important function of catalyst for Holmes's mental processes. [...] From the writer's point of view, Doyle knew the importance of having someone to whom the detective can make enigmatic remarks, a consciousness that's privy to facts in the case without being in on the conclusions drawn from them until the proper time. Any character who performs these functions in a mystery story has come to be known as a 'Watson'."

- In 1929, English crime writer and critic Ronald Knox stated as one of his rules for fledgling writers of detective fiction as that

- "the stupid friend of the detective, the Watson, must not conceal from the reader any thoughts which pass through his mind; his intelligence must be slightly, but very slightly, below that of the average reader."

- See also: Audience surrogate

Adaptations in Film and Television[edit]

Film[edit]

In some film adaptations, in particular those featuring the comic skills of the actor Nigel Bruce, Watson became more of a caricature than a character. The Rathbone-Bruce films portrayed Watson as an incompetent bungler.[citation needed] Modern treatments, however, have returned to the roots of the Conan Doyle stories and have depicted a more sympathetic and competent Watson. The most famous examples of this restored image of Watson are the portrayals of Watson by David Burke and later by Edward Hardwicke in the 1980s television series The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, The Return of Sherlock Holmes, The Casebook of Sherlock Holmes and The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes, all starring Jeremy Brett as Holmes.

Another well-liked depiction[citation needed] was actor André Morell's portrayal of Watson in the 1959 film version of The Hound of the Baskervilles. Morell was particularly keen that his version of Watson should be closer to that originally depicted in Conan Doyle's stories, and away from the incompetent, bungling stereotype established by Nigel Bruce's interpretation of the role.[8] Other depictions include Robert Duvall opposite Nicol Williamson's Holmes in The Seven-Per-Cent Solution (1978), Donald Houston, who played Watson to John Neville's Holmes in A Study in Terror (1965); a rather belligerent, acerbic Watson portrayed by Colin Blakely in Billy Wilder's The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (1970), in which Holmes was played by Robert Stephens (who starts the rumour that they are homosexual lovers so women will not chase after him); and James Mason's portrayal in Murder by Decree (1978), with Christopher Plummer as Holmes. Ian Hart portrayed a young, capable and fit Watson twice for BBC Television, once opposite Richard Roxburgh as Holmes (in a 2002 adaptation of The Hound of the Baskervilles) and for a second time opposite Rupert Everett as the Great Detective in the new story Sherlock Holmes and the Case of the Silk Stocking (2004).

In the Soviet/Russian Sherlock Holmes film series directed by Igor Maslennikov Dr. Watson was played by Vitaly Solomin. He is portrayed in the book as a brave and intelligent man, but not especially physically strong.

In the 1988 parody film Without a Clue, the roles of a bungling Watson and an extremely competent Holmes are reversed. In the film, Holmes (Michael Caine) is an invention of Watson (Ben Kingsley) played by an alcoholic actor; when Watson initially offered suggestions on how to solve a case to some visiting policemen, he was at the time applying for a post in an exclusive medical practice, and so invented the fictional Holmes to avoid attracting attention to himself, continuing the "lie" of Holmes's existence after he failed to get the post. At the same time, the film's Watson becomes increasingly frustrated that his own talents are unrecognised, and unavailingly attempts to win celebrity for himself as "the Crime Doctor."[citation needed]

In the 2009 Warner Bros. film Sherlock Holmes directed by Guy Ritchie, Jude Law portrays Watson as brave, intelligent, resolute, and thoroughly professional, as well as a somewhat competent detective in his own right. Apart from being armed with his trademark sidearm, his film incarnation is also a capable swordsman. The film portrays Watson as having a gambling problem, which William S. Baring-Gould had inferred from a reference in "The Adventure of the Dancing Men" to Holmes keeping Watson's cheque book locked in a drawer in his desk.[9] Law also portrayed Watson in the 2011 sequel; Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows.

Watson appears on the 2010 direct-to-DVD Asylum film Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes, a science fiction reinvention in which he is portrayed by actor Gareth David-Lloyd. At the beginning of the film, Watson is an elderly man portrayed by David Shackleton during the Blitz in 1940. He tells his nurse the tale of the adventure which he and Holmes vowed never to tell the public. In 1889, he is a home doctor and personal physician and biographer of Sherlock Holmes (Ben Syder), who often teases that Watson is quite a ladies-man and action hero. He helps Holmes battle a criminal genius called Spring-Heeled Jack and his robotic creatures which help him commit his crimes.

Television[edit]

In the TV series, Sherlock Holmes in the 22nd Century, although Watson is long dead, Holmes acquires a 'new' Watson in the form of a robot; originally the property of Inspector Lestrade's descendant, when Lestrade instructed the robot to read up on Sherlock Holmes, the robot downloaded all of the stories into its database, with the result that it now believes itself to be Watson, although still capable of accessing various databases; Holmes goes on to treat the robot as such as he concludes that its spirit is Watson, even if the body is not.

In 2010, the BBC began screening the TV series Sherlock, setting the characters of Holmes and Watson in contemporary London. John Watson, played by Martin Freeman, is again portrayed as a British army doctor, but wounded in the recent conflict in Afghanistan.[10]

The 2012 CBS modern adapation Elementary sees the typically male character changed to a female one. Lucy Liu portrays Joan Watson, an ex-surgeon turned sober companion- suspected by Holmes to be the result of her losing her career after a malpractice case involving the death of a patient- who is appointed to recovering drug addict Sherlock Holmes.

Other Adaptations[edit]

Stephen King, the American horror novelist, wrote a short story called "The Doctor's Case" in the collection Nightmares & Dreamscapes, where Watson actually solves the case instead of Holmes.

Watson was also portrayed by English-born actor Michael Williams for the BBC Radio adaptation of the complete run of the Holmes canon from November 1989 to July 1998. Williams, together with Clive Merrison, who played Holmes, are the only actors who have portrayed the Conan Doyle characters in all the short stories and novels of the canon. After Williams' death, the BBC continued the shows with The Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. Four series were made, all written by Bert Coules who had been the head writer on the complete canon project, with Andrew Sachs starring opposite Merrison. Sachs carried on the standard set by Michael Williams, portraying Watson as Conan Doyle set him down.

In January 1998, Jim French Productions received the rights from the estate of Dame Jean Conan Doyle to produce new radio stories of Holmes and Watson. Lawrence Albert plays Watson to the Holmes of first John Gilbert and later John Patrick Lowrie.

In popular culture[edit]

- Although "Elementary, my dear Watson" is perhaps Holmes's best-known catch phrase, he never uses exactly those words in any of the books written by A. Conan Doyle.[11][12]

- Microsoft named the debugger in Microsoft Windows "Doctor Watson".

- In the television series House, the character of Dr. James Wilson is meant to be a direct reference to Watson (with House himself being a direct reference to Holmes).[13] In addition to the similarity of their names, Wilson serves in the show as House's only real friend and confidant, and occasionally assists him in solving particularly difficult cases.

- In the TV series Sanctuary, Watson is a member of "The Five" and the actual detective in the Conan Doyle stories.[14] The character of Holmes is created and Watson is made his sidekick at Watson's request to Conan Doyle.[14]

- In the TV series Star Trek: The Next Generation, the character Geordi La Forge takes on the role of Dr. Watson in holodeck simulations with his shipmate and friend, Data.[15]

- In the first season of The Muppet Show there is a skit starring Rowlf the Dog as Sherlock Holmes and Baskersville the hound as Dr. Watson that is titled "The Case of the Disappearing Clues."

- American author Michael Mallory began a series of stories in the mid-1990s featuring Watson's mysterious second wife, whom he called Amelia Watson.[16] In Sherlock Holmes's War of the Worlds, Watson's second wife is Violet Hunter, from "The Adventure of the Copper Beeches".

- Watson appears as a supporting character in several of American author Laurie R. King's Mary Russell detective novels. The novels are told from Russell's point of view. The series begins with The Beekeeper's Apprentice (published in 1994) with the latest being Garment of Shadows (published in September of 2012). Over the course of the novels, Mary Russell meets, and eventually marries the aging Holmes, who has (semi)retired from his London practice. Watson, who is now in private practice, does not appear until later in the series and is treated as a rather paternalistic old duffer with typical Victorian attitudes toward women, but who still retains his nerve and his taste for adventure. The novels cover the time period between 1915 and the 1920's.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Notes

- ^ The Hound of the Baskervilles/Chapter 10 Wikisource. Retrieved on 23 August 2011.

- ^ Arthur Conan Doyle, "A Study in Scarlet", subtitle.

- ^ The Problem of Thor Bridge Wikisource. Retrieved on 23 August 2011.

- ^ Dorothy L. Sayers, "Dr. Watson's Christian Name," in Unpopular Opinions (London: Victor Gollancz, 1946), 148–151.

- ^ A Study in Scarlet/Part 1/Chapter 1 Wikisource. Retrieved on 23 August 2011.

- ^ A Study in Scarlet

- ^ Literary Qualities of The Hound of the Baskervilles | Novel Summaries Analysis. Novelexplorer.com (26 January 2009). Retrieved on 23 August 2011.

- ^ Kinsey, Wayne (2002). Hammer Films—The Bray Studios Years. Richmond: Reynolds & Hearn Ltd. p. 133. ISBN 1-903111-11-0.

- ^ Baring-Gould, William S. (1967). The Annotated Sherlock Holmes. Vol 2, pp. 527–528.

- ^ AP (16 August 2009). "Life outside The Office for Martin Freeman". Wales on Sunday. Western Mail and Echo.

- ^ Tom Burnham, The Dictionary of Misinformation, Thomas Y. Crowell, 1976.

- ^ Snopes.com, 'Elementary, My Dear Watson'. 2006.07.02.

- ^ 'House'-a-palooza, part 2: Robert Sean Leonard. Featuresblogs.chicagotribune.com (1 May 2006). Retrieved on 23 August 2011.

- ^ a b James Watson. Sanctuary.wikia.com (14 August 2011). Retrieved on 23 August 2011.

- ^ Elementary, Dear Data. Memory-alpha.org. Retrieved on 23 August 2011.

- ^ Mallory, Michael (2009). The Adventures of the Second Mrs. Watson. Dallas: Top Publications. ISBN 1-929976-57-7

External links[edit]

- The Sherlock Holmes Museum

- Who2 biography

- Sherlock Holmes Public Library

- An analytical profile of The Good Doctor

- Speculation on Dr. Watson's Six Wives

- A post-colonial canonical and cultural revision of Conan Doyle's Holmes narratives

Category:Fictional characters introduced in 1887 Category:Fictional English people Category:Fictional soldiers Category:Fictional surgeons Category:Fictional writers Category:Horror film characters Category:Sherlock Holmes characters Category:Sidekicks in literature