User:KnightOrnstein/sandbox

Article Evaluation[edit]

- At first glance, the article seemed lengthy, and for that reason alone, good

- After a couple of readings plus looking over the talk page, there problems that begin to rise

- Firstly, some of the descriptions are wrong: i.e. Triglyphs are described as two part separators for metopes when they should be three part

- As an edit to the point above, I see that it states "two vertical grooves" and in that sense is actually correct

- There is a sense of favoritism to the idea that wood was the starting base of the Doric order

- Continuing with above, I believe that is one of many theories and while it sees the most accepted, there are others that the article completely disregards

- Once again continuing with above, other theories aren't even mentioned at all

- A look at the talk page shows that many of the comments have been entered and used to revise the article

- It seems much more up to date, but it feels as if there are still some issues (it could just be me)

- Returning to the talk page, it seems this article at one point had a lot of unnecessary parts that have long since been removed

- The sources seem all there and all the links work, so that's good at least

- Finally, either I'm unsure where to look or the article isn't rated

- With regards to the latter above, the article might not be rated for providing only a bare minimum

- As a last bullet, I think that's everything I noticed, but I'm sure I missed more with my hazy Greco-Roman knowledge

This is a user sandbox of KnightOrnstein. You can use it for testing or practicing edits.

This is a user sandbox of KnightOrnstein. You can use it for testing or practicing edits.

This is not the sandbox where you should draft your assigned article for a dashboard.wikiedu.org course.

To find the right sandbox for your assignment, visit your Dashboard course page and follow the Sandbox Draft link for your assigned article in the My Articles section.

My Plans for the Future[edit]

I plan to continue fixing up the article on the Doric Order. Below are the steps I wish to take in order to do so.

- The article needs to be rewritten. This is not to say it's bad since most of the information is actually quite factual and correct, but the order(no pun intended) needs to be fixed. As of now, the history section just seems disorganized and overwhelming. There are too many thoughts going in every direction and it's not stream lined well. It acts both as a historic and architectural guide that is a bit awkward. Rather, I believe it might be better with a quick introduction summary, then a description of the Greek and Roman Doric orders, followed by a brief history starting with the origin and a timeline with examples.

- The article could use a bit more information. I wish to add more specifically to the history and origin. I would like to share more information for the purpose of a more detailed timeline and cohesive time line.

- Finally, there will be a necessity for more pictures. All these changes and possibly new examples will require some picture moving and placing both of the old and new.

I believe that if I do the above the article will be much better. Of course, this still requires the go ahead and thoughts of my Professor.

Here is a short Bibliography.

Lawrence, A. W., and R. A. Tomlinson. Greek Architecture. 5th Ed. / Revised by R.A. Tomlinson. Edited by Yale University Press Pelican History of Art. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996.

Quincey, A. The Oxford Companion to Architecture. Edited by Patrick Goode. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Rhodes, Robin Francis. Architecture and Meaning on the Athenian Acropolis. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Rhodes, Robin Francis. "Early Corinthian Architecture and the Origins of the Doric Order." American Journal of Archaeology 91, no. 3 (1987): 477-80. doi:10.2307/505370.

Working and Finalized Draft[edit]

See below.

Doric Order[edit]

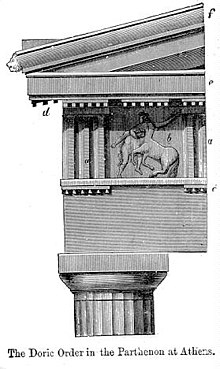

The Doric order was one of the three orders of ancient Greek and later Roman architecture; the other two canonical orders were the Ionic and the Corinthian. The Doric is most easily recognised by the simple circular capitals at the top of columns. It was the earliest and in its essence the simplest of the orders, though still with complex details in the entablature above.

Like the other orders, the Doric was adapted by Roman Empire and Renaissance architects. These later versions retained some of the base characteristics, but also became a creation of their time. These include the use of different materials such as concrete and the creation of non-functioning and purely decorative columns. More often, they used the Tuscan order which was a term elaborated for nationalistic reasons by Italian Renaissance writers. The Tuscan order is in a way, simplified Doric order. Some of its characteristics included un-fluted columns and a simpler entablature with no triglyphs or guttae. The Doric order was much used in Greek Revival architecture from the 18th century to the present day. These more modern structures that serve as recalls to the Doric often used the original Greek style over the Roman or Renaissance versions.

Since at least Vitruvius, it has been customary for writers to associate the Doric with masculine virtues.[1] It is also normally the cheapest of the orders to use. When the three orders are used one above the other, it is usual for the Doric to be at the bottom, with the Ionic and then the Corinthian above, and the Doric, as "strongest", is often used on the ground floor below another order in the story above.[2]

History[edit]

Greek[edit]

Their are many theories as to the creation of the Doric order. The term Doric is believed to have originated from the Greek-speaking Dorian tribes.[3] One belief is that the Doric order is the result of early wood prototypes of previous temples.[4] With no hard proof and the sudden appearance of stone temples from one period after the other, this becomes mostly speculation. Another belief is that the Doric was inspired by the architecture of Egypt.[5] With the Greeks being present in Ancient Egypt as soon the 7th-century BC, it is possible that Greek traders were inspired by the structures they saw in what they would consider foreign land. Finally, another theory states that the inspiration for the Doric came from Mycenae. At the ruins of this civilization lies architecture very similar to the Doric order. It is also in Greece, which would make it very accessible.

Some of the earliest examples of the Doric order come from the 7th-century BC. These examples include the Temple of Apollo at Corinth and the Temple of Zeus at Nemea.[6] Other examples of the Doric order include the 6th-century BC temples at Paestum in southern Italy, a region called Magna Graecia, which was settled by Greek colonists. Compared to later versions, the columns are much more massive, with a strong entasis or swelling, and wider capitals.

The Temple of the Delians is another example and is a "peripteral" Doric order temple, the largest of three dedicated to Apollo on the island of Delos. It was begun in 478 BC and never completely finished. It is "hexastyle", with six columns across the pedimented end and thirteen along each long face. All the columns are centered under a triglyph in the frieze, except for the corner columns. The plain, unfluted shafts on the columns stand directly on the stylobate, without bases. The recessed "necking" in the nature of fluting at the top of the shafts and the wide cushionlike echinus may be interpreted as slightly self-conscious archaising features, for Delos is Apollo's ancient birthplace. However, the similar fluting at the base of the shafts might indicate an intention for the plain shafts to be capable of wrapping in drapery. Another example and a classic statement of the Greek Doric order is the Temple of Hephaestus in Athens, built about 447 BC. The contemporary Parthenon, the largest temple in classical Athens, is also in the Doric order, although the sculptural enrichment is more familiar in the Ionic order: the Greeks were never as doctrinaire in the use of the Classical vocabulary as Renaissance theorists or neoclassical architects. The detail, part of the basic vocabulary of trained architects from the later 18th century onwards, shows how the width of the metopes was flexible: here they bear the famous sculptures including the battle of Lapiths and Centaurs.

Roman[edit]

The Roman Empire which came after Greece, was a powerful engine of conquest. They not only conquered other territories, but also assimilated their cultures. This meant that their was a wide variety of artistic styles in the Roman Empire. As their influence spread, the Romans eventually came into contact with Greece. They found similarities in their building ideas, such as the construction of structures for monarchs or similar powerful individuals. Continuing and growing contact with Greece, Romans became more and more fond of their architecture.[7] Rome would then adopt Greek architecture for their own creations and give it a style unique to them. At its base, the Roman Doric is very nearly identical to the Greek. Their similarities would end in the materials used by Romans such as concrete. As the Roman empire grew, so did the difference as their structures took new shapes that would simply echo the spirit of their Greek roots.

Popular examples of Roman Architecture that echo the roots of Greek architecture are the Flavian Amphitheater or Roman Colosseum constructed in the 1st-century AD and the Pantheon constructed in the 2nd-century AD. In both cases the structures were made from concrete rather than stone. Concrete was a strong and durable substance that had an aggregate mix that could be altered. This allowed for Roman to build structures with strong bases and light tops. It made their architecture much larger and grander in appearance that that of Greece. Because of this, columns could be singular monoliths rather then separate pieces of stacked stone. In fact, the strength and durability of concrete allowed for most columns to be decorative. Rather than supporting the structure, they are now simply their to showcase a certain appearance. This can be most easily seen in the Colosseum. With regards to the Pantheon, while it has a classic Greek style appearance with a pediment at the front, it is not decorated when compared to a Greek equivalent and is quite bare in appearance.

Characteristics[edit]

Greek[edit]

The Greeks were said to be the first to create and use the Classical orders. Their is an idea that while Greek architects did exist, the conservative and simple nature of the Doric order meant that it could easily be put together by almost any group without a the need for a blueprint or architect.[8] It is believed that the Doric is the first and oldest.[9] The Doric is characterized by simple designs when compared to the Ionic or Corinthian. It is considered a masculine order and is often used to house male Gods. When paired with the other orders, it is always placed at the bottom as it is the most stable and also symbolizes masculinity through its strength. The Greek Doric column was fluted or smooth-surfaced and had no base, dropping straight into the stylobate or platform on which the temple or other building stood. These columns were absent of many intricacies and sported a simple capital with a design that looked similar to a flattened mushroom.[9] This was due to the capital being under a square cushion that is very wide in early versions, but later more restrained. From there, a slab of stone where decorations could be placed known as an entablature rested. Above the usually plain architrave of this entablature is a frieze with alternating triglyphs and metopes.[9] The triglyphs are usually square or rectangular in nature with minimal decoration other than a slight bit of fluting that creates a pair of divets. This design gives the a look similar to a columns and the three-sectioned appearance gives them their name. The metopes are a similar square or rectangular shape that portray an actual image. The subject of the image is dependent on the architect and the purpose of the temple. Finally, above the entablature is the pediment. This large triangular shaped slab that acted both as a roof and support locker was either left blank, or decorated similar to the metopes. The decorations take advantage of the entire space.

Vitruvius[edit]

Vitruvius was presumably a free-born Roman Citizen who was a writer, architect, and military character. Through his service, he discovered many structures from different lands. He eventually wrote about these structures in his surviving book, De architectura. Here, he explains the structures' method of creation, significance, and importance. When it came to Greek temples, Vitruvius had a very calculated method of construction. This very same construction seems to be the model that is used by many Roman architects. Modules were used to measure out the appropriate dimension of each structure. They also dictated the spacing, placement, and size of triglyphs and metopes on the entablature.[10] Everything within a structure was measurable in some finite way that allowed for what Vitruvius considered perfect proportion. He stated that, "Once the module has been decided, all the calculations for the proportions of the whole project can be carried out."[11] There is a very calculated and analytical approach in the construction of the Doric order in Vitruvius' eyes. While the characteristics do not differ from the Greek, Vitruvius did not see construction as a simple task that could be accomplished by just any one man or group as compared to how the Greeks thought of it. He believed the Doric order called for a brilliant mind or minds in order to succeed. While Vitruvius agrees with the simple aesthetic of the Doric order, he also believes that it is this simplicity that causes complication. Vitruvius makes mention of Hermogenes' choice to forgo with the Doric order in some of his structures, saying that, "He did not do this because the species and type of Doric are unattractive, but because it it restrictive and inconvenient in working out the distribution."[12] In other words, Vitruvius saw the Doric and its elements to be fine and appropriate, echoing many similarities to the elements placed upon the Doric by the Greeks. He does however, caution from its use since he believes their is a discrepancy in the process of measuring and proportioning that the other orders do not suffer from as much.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Summerson, 14-15

- ^ Palladio, First Book, Chapter 12

- ^ Ian Jenkins, Greek Architecture And Its Sculpture (Cambridge, Massachussetts: Harvard University Press, 2006), 15.

- ^ Idid. 16.

- ^ Ibid. 16-17.

- ^ Robin F. Rhodes, "Early Corinthian Architecture and the Origins of the Doric Order" in the American Journal of Archaeology 91, no. 3 (1987), 478.

- ^ Ulrich, Roger and Caroline Quenemon (2013). A Companion to Roman Architecture. Wiley. pp. 27–28.

- ^ Ian Jenkins, Greek Architecture And Its Sculpture (Cambridge, Massachussetts: Harvard University Press, 2006), 29-30.

- ^ a b c A, Quiney (2009). "Doric Order" in The Oxford Companion to Architecture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Virtruvius, Ten Books on Architecture, ed. by Ingrid Rowland and Thomas Noble Howe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 5.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

Sources(Will Update)[edit]

- Alexander Tzonis, Classical Architecture: The Poetics of Order (Alexander Tzonis website)

- Georges Gromort, The Elements of Classical Architecture

- James Stevens Curl, Classical Architecture: An Introduction to Its Vocabulary and Essentials, with a Select Glossary of Terms

- Jenkins, Ian. Greek Architecture And Its Sculpture. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. 2006.

- Labeled Doric Column

- Quiney, A. "Doric Order" in The Oxford Companion to Architecture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Summerson, John, The Classical Language of Architecture, 1980 edition, Thames and Hudson World of Art series, ISBN 0500201773

- Vitruvius. Ten Books on Architecture. Edited by Ingrid Rowland and Thomas Noble Howe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1999.

External links[edit]

![]() Media related to Doric columns at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Doric columns at Wikimedia Commons

Category:Orders of columns

Category:Ancient Greek architecture

Order