User:Ledbetter33/samplespace

Rare disasters are economic events that are infrequent and large in magnitude, having a negative effect on an economy. Rare disasters are important because they provide an explanation of the equity premium puzzle, the behavior of interest rates, and other economic phenomenon.

The parameters for a rare disaster are a substantial drop in GDP and at least a 10% decrease in consumption. Examples include financial disasters(The Great Depression, Asian Financial Crisis), wars(World War I and World War II, Regional conflicts), epidemics(Influenza Outbreak, Asian Flu), weather events(Tsunamis and Earthquakes), however any event that has a substantial impact on GDP and consumption could be considered a rare disaster.

The idea was first proposed by Rietz in 1988 as a way to explain the equity premium puzzle. Since then other economists have added to and strengthened the idea with evidence but many economists are still skeptical of the theory.

Model[edit]

The model set forth by Barro is based upon the Lucas's fruit tree model of asset pricing with exogenous, stochastic production. The economy is closed, the amount of trees are fixed, output equals consumption(), and there is no investment or depreciation. is the output of all the trees in the economy and is the price of the periods fruit(the equity claim). The equation below shows the gross return on the fruit tree in one period.[1]

In order to model rare disasters Barro introduces the below equation, which is a stochastic process for aggregate output growth. In the model there are three types of economic shocks.

a.) Normal iid shocks

b.) Type disasters which involve sharp contractions in output but no default on debt.

c.) Type disasters which involve sharp contractions in output and at least a partial default on debt

The type ω () models low probability disasters and is a random iid variable. They are assumed to be independent so they are interchangeable in the equation. Then from the above equation, the magnitude of the contraction from is determined by the following equation.

In this equation, p is the probability per unit of time that a disaster will occur in each period. If the disaster occurs, b is the factor by which consumption will shrink. The model requires a p that is small and a b that large to correctly model rare disasters. In Barro's analysis d is also used to deal with the problem of the partial default on bonds. He reasons that p and d interact differently with a rising p leading to lower risk-free rates and a rising d leading to higher risk-free rates. The characteristics of a rare disaster are a rising p and d, so the overall effect is unclear before the actual disaster occurs.

Applications[edit]

In promoting his theory of the impact of rare disasters on the asset markets, Barro has suggested that rare disaster framework can be used to explain other events in finance and economics.

The Equity Premium[edit]

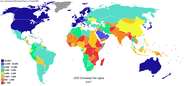

Much of the equity premium puzzle can be explained by the rare disasters scenarios proposed by Barro and Rietz. The basic reasoning is that if people are aware that rare disasters(i.e the Great Depression or WW1 and WW2) may occur, but the disaster never occurs during their lives, then the equity premium will appear high. Barro and subsequent economists have provided historical evidence to support this claim. Using this evidence, Barro shows that rare disasters occur frequently and in large magnitude, in economies around the world from a period from the mid 1800s to the present day.

Further, the evidence shows that in the long run the risk premium is around 5.0% in most countries. However, when looking at specific periods of time this premium may be higher or lower. For example, if a data set containing the period of the Great Depression(a rare disaster) is observed, then the equity premium will be about 0.4%. However, if the data set was the period of time thirty years after World War II in the United States, then you would see a much higher equity premium[1]

Risk-Free Interest Rate Behavior[edit]

The risk-free interest rate (the interest received on fixed income like bonds) may also be explained by rare disasters. Using data in the United States, the rare disaster model shows that the risk free rate falls by a large margin(from .127 to .035) when a rare disaster with the probability of .017 is introduced into the data set. [1]

Furthermore, Barro defends the criticisms about the behavior of the risk free rate raised by Mehra with respect to the Great Depression and events such as the Cuban Missile Crisis. He reasons that two effects go into people's expectation of rare disasters-the probability of a rare disaster and the probability of default. In an event that has the possibility of nuclear war(like the Cuban Missile Crisis), the probability of a disaster would rise and therefore decrease interest rates. However, the probability of government default on bonds also increases, because of the possible destruction of countries, which raises the rate on bonds. These to forces counteract and lead to ambiguity.[2]

History[edit]

Prescott and Mehra first proposed the Equity Premium Puzzle in 1985. In 1988, Rietz suggested that large and infrequent economic shocks could explain the equity premium(the premium of securities over fixed income assets). However, it was not deemed feasible at the time because it seemed that such events were too rare and could not occur in reality.[2] The theory was forgotten until 2005 when Robert Barro provided evidence of nations from around the world from the 19th and 20th century, showing that these events were possible and have happened. Since his papers, others have submitted different ideas regarding rare disasters impact on other economic phenomenon.[1] However, many economists remain skeptical about how effectively rare disasters explain the equity premium puzzle.

Mehra still expresses doubt as to the validity of the theory. He agrees that Barro's model and the subsequent additions by other economists have solved many of the concerns he had with the original rare disaster model of Rietz. However,[3]

Controversy[edit]

Rajnish Mehra was skeptical of Reitz claim that rare disasters explain the equity premium and real interest rate behavior, because the rare disaster that Rietz had specified had never occurred in the united states. Rietz suggested 25-97% drops but this has never happened in the United States. Even if this was true there are several other flaws regarding his model, parameters, and supporting evidence. The model Rietz presented did not compensate for a partial default on bond holders do due rapid inflation. Further, the risk aversion in parameter was used inconsistently in his analysis. For example, a value of 10 was used to show a 25% drop in consumption but a value of 1 is used to explain stock returns and consumption. Finally, more historical evidence was needed to give the theory proper support. For example, the perceived probability of a rare disaster should have been low before the atomic bomb was dropped and must have been higher before the Cuban Missile Crisis than after. Therefore, real interest rates should have correlated with these events but the historical record does not support this. Also the Great Depression should have raised the expectation of another rare disaster occuring and interest rates should have risen after WW2 and the end of the depression but they did not. Mehra concluded that Rietz's scenario was far too extreme to resolve the puzzle.[2]

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c d Barro, Robert. "Rare Disasters and Asset Markets in the Twentieth Century" (PDF). The Quarterly Journal of Economics. pp. pp. Retrieved 2009-03-09.

{{cite web}}: Text "10-20." ignored (help) Cite error: The named reference "Barro10" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b c Rajnish Mehra. "The Equity Premium Puzzle. A Solution?" (PDF). Journal of Monetary Economics. Retrieved 2009-03-09.

- ^ * Ranjish Mehra. "The Equity Premium Puzzle: A Review" (PDF). Foundations and Trends® in Finance: 2008 Vol. 2: No 1, pp 1-81. Retrieved 2009-03-09.

Bibliography[edit]

- Rajnish Mehra and Edward C. Prescott(1985). "The Equity Premium A Puzzle*" (PDF). Journal of Monetary Economics. Retrieved 2009-03-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Rajnish Mehra and Edward C. Prescott(1988). "The Equity Risk Premium: A Solution?" (PDF). Journal of Monetary Economics. Retrieved 2009-03-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- New Economist(2005). "New Economist on Barro and the Equity Premium Puzzle". Mehra. Retrieved 2009-03-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Help[edit]

- References Help Pages:

Put references in standard bibliographic form, using author, date, article name, name of work (e.g., the web site), date retreived from web, etc.

Read about citing sources here: Wikipedia:Citing_sources See also: Help:Footnotes - mechanism for <ref> tags and footnotes

I am now recommending that people use the citation templates that appear here:

The citation template for web articles is Template:Cite_web

For long quotations, use a quotation template: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CAT:QUOTE