User:Ltwin/Sandbox 13

Background

[edit]Jewish origins

[edit]Not in article: The basic tenets of Judaism were ethical monotheism, the Torah (or Law), and eschatological hope in a future messianic age.[1]

Christianity originated as a minor sect within Second Temple Judaism,[2] a form of Judaism named after the Second Temple built c. 516 BC after the Babylonian captivity. While the Persian Empire permitted Jews to return to their homeland of Judea, there was no longer a native Jewish monarchy. Instead, political power devolved to the high priest, who served as an intermediary between the Jewish people and the empire. This arrangement continued after the region was conquered by Alexander the Great (356–323 BC).[3] After Alexander's death, the region was ruled by Ptolemaic Egypt (c. 301 – c. 200 BC) and then the Seleucid Empire (c. 200 – c. 142 BC). The anti-Jewish policies of Antiochus IV Epiphanes (r. 175 – 164 BC) sparked the Maccabean Revolt in 167 BC, which culminated in the establishment of an independent Judea under the Hasmoneans, who ruled as kings and high priests. This independence would last until 63 BC when Judea became a client state of the Roman Empire.[4]

The central tenets of Second Temple Judaism revolved around monotheism and the belief that Jews were a chosen people. As part of their covenant with God, Jews were obligated to obey the Torah. In return, they were given the land of Israel and the city of Jerusalem, where God dwelled in the Temple. Apocalyptic and wisdom literature had a major influence on Second Temple Judaism.[5]

Alexander's conquests initiated the Hellenistic period when the Ancient Near East underwent Hellenization (the spread of Greek culture). Judaism was thereafter both culturally and politically part of the Hellenistic world; however, Hellenistic Judaism was stronger among diaspora Jews than among those living in the land of Israel.[6] Diaspora Jews spoke Koine Greek, and the Jews of Alexandria produced a Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible called the Septuagint. The Septuagint was the translation of the Old Testament used by early Christians.[7] Diaspora Jews continued to make pilgrimage to the Temple, but they started forming local religious institutions called synagogues as early as the 3rd century BC.[8]

The Maccabean Revolt caused Judaism to divide into competing sects with different theological and political goals,[9] each adopting different stances towards Hellenization. The main sects were the Sadducees, Pharisees, and Essenes.[10] The Sadducees were mainly Jerusalem aristocrats intent on maintaining control over Jewish politics and religion.[11] Sadducee religion was focused on the Temple and its rituals. The Pharisees emphasized personal piety and interpreted the Torah in ways that provided religious guidance for daily life. Unlike Sadducees, the Pharisees believed in the resurrection of the dead and an afterlife. The Essenes rejected Temple worship, which they believed was defiled by wicked priests. They were part of a broader apocalyptic movement in Judaism, which believed the end times were at hand when God would restore Israel.[12] Roman rule exacerbated these religious tensions and led the radical Zealots to separate from the Pharisees. The territories of Roman Judea and Galilee were frequently troubled by insurrection and messianic claimants.[13]

Messiah (Hebrew: meshiach) means "anointed" and is used in the Old Testament to designate Jewish kings and in some cases priests and prophets whose status was symbolized by being anointed with holy anointing oil. The term is most associated with King David, to whom God promised an eternal kingdom (2 Samuel 7:11–17). After the destruction of David's kingdom and lineage, this promise was reaffirmed by the prophets Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel, who foresaw a future king from the House of David who would establish and reign over an idealized kingdom.[14]

In the Second Temple period, there was no consensus on who the messiah would be or what he would do.[15] Most commonly, he was imagined to be an end times son of David going about the business of "executing judgment, defeating the enemies of God, reigning over a restored Israel, [and] establishing unending peace".[16] Yet, there were other kinds of messianic figures proposed as well—the perfect priest or the celestial Son of Man who brings about the resurrection of the dead and the final judgment.[17][18]

Greco-Roman context

[edit]Not in article yet By the time Christianity began in the 1st century, the societies of the Ancient Near East and the Roman Empire had undergone Hellenization (the spread of Greek culture) during the Hellenistic period, which started with the rise of Alexander the Great (356–323 BC). The New Testament was written in Koine Greek, the lingua franca of the 1st century.[19]

Greek and Roman religion was polytheistic and focused around mythology and animal sacrifice. Through sacrifice, the people were purified and the relationship between humanity and the gods was maintained according to the principle of do ut des ("I give so that you might give").Within Greco-Roman polytheism were the mystery religions characterized by secretive rites of initiation, common meals, adherents' identification with the fate of a god, and hope for an afterlife or rebirth. Mystery religions had some similarities with Christianity.[20]

Jesus

[edit]

Christianity centers on the life and ministry of Jesus of Nazareth, who lived c. 4 BC – c. AD 33. Jesus left no writings of his own, and most information about him comes from early Christian writings that now form part of the New Testament. The earliest of these are the Pauline epistles, letters written to various Christian congregations by Paul the Apostle in the 50s AD. The four canonical gospels of Matthew (c. AD 80 – c. AD 90), Mark (c. AD 70), Luke (c. AD 80 – c. AD 90), and John (written at the end of the 1st century) are ancient biographies of Jesus' life.[21]

Jesus grew up in Nazareth, a city in Galilee. He was baptized in the Jordan River by John the Baptist. Jesus began his own ministry when he was around 30 years old around the time of the Baptist's arrest and execution. Jesus' message centered on the coming of the Kingdom of God (in Jewish eschatology a future when God actively rules over the world in justice, mercy, and peace). Jesus urged his followers to repent in preparation for the kingdom's coming. His ethical teachings included loving one's enemies (Matthew 5:44; Luke 6:28–35), giving alms and fasting in secret (Matthew 6:4–18), not serving both God and Mammon (Matthew 6:24; Luke 16:13), and not judging others (Matthew 7:1–2; Luke 6:37–38). These teachings are highlighted in the Sermon on the Mount and the Lord's Prayer. Jesus chose 12 Disciples who represented the 12 tribes of Israel (10 of which were "lost" by this time) to symbolize the full restoration of Israel that would be accomplished through him.[22]

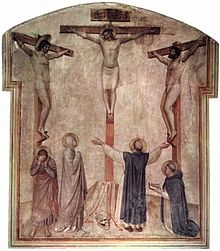

The gospel accounts provide insight into what early Christians believed about Jesus.[23] As the Christ or "Anointed One" (Greek: Christos), Jesus is identified as the fulfillment of messianic prophecies in the Hebrew scriptures. Through the accounts of his miraculous virgin birth, the gospels present Jesus as the Son of God.[24] The gospels describe the miracles of Jesus which served to authenticate his message and reveal a foretaste of the coming kingdom.[25] The gospel accounts conclude with a description of the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus, ultimately leading to his Ascension into Heaven. Jesus' victory over death became the central belief of Christianity.[26] In the words of historian Diarmaid MacCulloch:[27]

Whether through some mass delusion, some colossal act of wishful thinking, or through witness to a power or force beyond any definition known to Western historical analysis, those who had known Jesus in life and had felt the shattering disappointment of his death proclaimed that he lived still, that he loved them still, and that he was to return to earth from the Heaven which he had now entered, to love and save from destruction all who acknowledged him as Lord.

For his followers, Jesus' death inaugurated a New Covenant between God and his people.[28] The apostle Paul, in his epistles, taught that Jesus makes salvation possible. Through faith, believers experience union with Jesus and both share in his suffering and the hope of his resurrection.[29]

While they do not provide new information, non-Christian sources do confirm certain information found in the gospels. The Jewish historian Josephus referenced Jesus in his Antiquities of the Jews written c. AD 95. The paragraph, known as the Testimonium Flavianum, provides a brief summary of Jesus' life, but the original text has been altered by Christian interpolation.[30] The first Roman author to reference Jesus is Tacitus (c. AD 56 – c. 120), who wrote that Christians "took their name from Christus who was executed in the reign of Tiberius by the procurator Pontius Pilate" .[31]

1st century

[edit]The decades after the crucifixion of Jesus are known as the Apostolic Age because the Disciples (also known as Apostles) were still alive.[32] Important Christian sources for this period are the Pauline epistles and the Acts of the Apostles.[33]

Initial spread

[edit]

After the death of Jesus, his followers established Christian groups in cities, such as Jerusalem.[32] The movement quickly spread to Damascus and Antioch, capital of Roman Syria and one of the most important cities in the empire.[34] Early Christians referred to themselves as brethren, disciples or saints, but it was in Antioch, according to Acts 11:26, that they were first called Christians (Greek: Christianoi).[35]

According to the New Testament, Paul the apostle established Christian communities throughout the Mediterranean world.[32] He is known to have also spent some time in Arabia. After preaching in Syria, he turned his attention to the cities of Asia Minor. By the early 50s, he had moved on to Europe where he stopped in Philippi and then traveled to Thessalonica in Roman Macedonia. He then moved into mainland Greece, spending time in Athens and Corinth. While in Corinth, Paul wrote his Epistle to the Romans, indicating that there were already Christian groups in Rome. Some of these groups had been started by Paul's missionary associates Priscilla and Aquila and Epainetus.[36]

Social and professional networks played an important part in spreading the religion as members invited interested outsiders to secret Christian assemblies (Greek: ekklēsia) that met in private homes (see house church). Commerce and trade also played a role in Christianity's spread as Christian merchants traveled for business. Christianity appealed to marginalized groups (women, slaves) with its message that "in Christ there is neither Jew nor Greek, neither male nor female, neither slave nor free" (Galatians 3:28). Christians also provided social services to the poor, sick, and widows.[37] Women actively contributed to the Christian faith as disciples, missionaries, and more due to the large acceptance early Christianity offered.

Historian Keith Hopkins estimated that by AD 100 there were around 7,000 Christians (about 0.01 percent of the Roman Empire's population of 60 million).[38] Separate Christian groups maintained contact with each other through letters, visits from itinerant preachers, and the sharing of common texts, some of which were later collected in the New Testament.[32]

Jerusalem church

[edit]

Jerusalem was the first center of the Christian Church according to the Book of Acts.[40] The apostles lived and taught there for some time after Pentecost.[41] According to Acts, the early church was led by the Apostles, foremost among them Peter and John. When Peter left Jerusalem after Herod Agrippa I tried to kill him, James, brother of Jesus appears as the leader of the Jerusalem church.[41] Clement of Alexandria (c. 150–215 AD) called him Bishop of Jerusalem.[41] Peter, John and James were collectively recognized as the three pillars of the church (Galatians 2:9).[42]

At this early date, Christianity was still a Jewish sect. Christians in Jerusalem kept the Jewish Sabbath and continued to worship at the Temple. In commemoration of Jesus' resurrection, they gathered on Sunday for a communion meal. Initially, Christians kept the Jewish custom of fasting on Mondays and Thursdays. Later, the Christian fast days shifted to Wednesdays and Fridays (see Friday fast) in remembrance of Judas' betrayal and the crucifixion.[43]

James was killed on the order of the high priest in AD 62. He was succeeded as leader of the Jerusalem church by Simeon, another relative of Jesus.[44] During the First Jewish-Roman War (AD 66–73), Jerusalem and the Temple were destroyed after a brutal siege in AD 70.[41] Prophecies of the Second Temple's destruction are found in the synoptic gospels,[45] specifically in the Olivet Discourse.

According to a tradition recorded by Eusebius and Epiphanius of Salamis, the Jerusalem church fled to Pella at the outbreak of the First Jewish Revolt.[46][47] The church had returned to Jerusalem by AD 135, but the disruptions severely weakened the Jerusalem church's influence over the wider Christian church.[44]

Gentile Christians

[edit]

Jerusalem was the first center of the Christian Church according to the Book of Acts.[40] The apostles lived and taught there for some time after Pentecost.[41] James the Just, brother of Jesus was leader of the early Christian community in Jerusalem, and his other kinsmen likely held leadership positions in the surrounding area after the destruction of the city until its rebuilding as Aelia Capitolina in c. 130 AD, when all Jews were banished from Jerusalem.[41]

The first Gentiles to become Christians were God-fearers, people who believed in the truth of Judaism but had not become proselytes (see Cornelius the Centurion).[48] As Gentiles joined the young Christian movement, the question of whether they should convert to Judaism and observe the Torah (such as food laws, male circumcision, and Sabbath observance) gave rise to various answers. Some Christians demanded full observance of the Torah and required Gentile converts to become Jews. Others, such as Paul, believed that the Torah was no longer binding because of Jesus' death and resurrection. In the middle were Christians who believed Gentiles should follow some of the Torah but not all of it.[49]

In c. 48–50 AD, Barnabas and Paul went to Jerusalem to meet with the three Pillars of the Church:[40][50] James the Just, Peter, and John.[40][51] Later called the Council of Jerusalem, according to Pauline Christians, this meeting (among other things) confirmed the legitimacy of the evangelizing mission of Barnabas and Paul to the Gentiles. It also confirmed that Gentile converts were not obligated to follow the Mosaic Law,[51] especially the practice of male circumcision,[51] which was condemned as execrable and repulsive in the Greco-Roman world during the period of Hellenization of the Eastern Mediterranean,[57] and was especially adversed in Classical civilization from ancient Greeks and Romans, who valued the foreskin positively.[59] The resulting Apostolic Decree in Acts 15 is theorized to parallel the seven Noahide laws found in the Old Testament.[63] However, modern scholars dispute the connection between Acts 15 and the seven Noahide laws.[62] In roughly the same time period, rabbinic Jewish legal authorities made their circumcision requirement for Jewish boys even stricter.[64]

The primary issue which was addressed related to the requirement of circumcision, as the author of Acts relates, but other important matters arose as well, as the Apostolic Decree indicates.[51] The dispute was between those, such as the followers of the "Pillars of the Church", led by James, who believed, following his interpretation of the Great Commission, that the church must observe the Torah, i.e. the rules of traditional Judaism,[1] and Paul the Apostle, who called himself "Apostle to the Gentiles",[65] who believed there was no such necessity.[68] The main concern for the Apostle Paul, which he subsequently expressed in greater detail with his letters directed to the early Christian communities in Asia Minor, was the inclusion of Gentiles into God's New Covenant, sending the message that faith in Christ is sufficient for salvation.[69] (See also: Supersessionism, New Covenant, Antinomianism, Hellenistic Judaism, and Paul the Apostle and Judaism).

The Council of Jerusalem did not end the dispute, however.[51] There are indications that James still believed the Torah was binding on Jewish Christians. Galatians 2:11-14 describe "people from James" causing Peter and other Jewish Christians in Antioch to break table fellowship with Gentiles.[72] (See also: Incident at Antioch). Joel Marcus, professor of Christian origins, suggests that Peter's position may have lain somewhere between James and Paul, but that he probably leaned more toward James.[73] This is the start of a split between Jewish Christianity and Gentile (or Pauline) Christianity. While Jewish Christianity would remain important through the next few centuries, it would ultimately be pushed to the margins as Gentile Christianity became dominant. Jewish Christianity was also opposed by early Rabbinic Judaism, the successor to the Pharisees.[74] When Peter left Jerusalem after Herod Agrippa I tried to kill him, James appears as the principal authority of the early Christian church.[41] Clement of Alexandria (c. 150–215 AD) called him Bishop of Jerusalem.[41] A 2nd-century church historian, Hegesippus, wrote that the Sanhedrin martyred him in 62 AD.[41]

In 66 AD, the Jews revolted against Rome.[41] After a brutal siege, Jerusalem fell in 70 AD.[41] The city, including the Jewish Temple, was destroyed and the population was mostly killed or removed.[41] According to a tradition recorded by Eusebius and Epiphanius of Salamis, the Jerusalem church fled to Pella at the outbreak of the First Jewish Revolt.[46][47] According to Epiphanius of Salamis,[75][better source needed] the Cenacle survived at least to Hadrian's visit in 130 AD. A scattered population survived.[41] The Sanhedrin relocated to Jamnia.[76] Prophecies of the Second Temple's destruction are found in the Synoptic Gospels,[45] specifically in Jesus's Olivet Discourse.

1st century persecution

[edit]Early Christianity was diverse and lacked fully set beliefs.[35]

Romans had a negative perception of early Christians. The Roman historian Tacitus wrote that Christians were despised for their "abominations" and "hatred of humankind".[77] The belief that Christians hated humankind could refer to their refusal to participate in social activities connected to pagan worship—these included most social activities such as the theater, the army, sports, and classical literature. They also refused to worship the Roman emperor, like Jews. Nonetheless, Romans were more lenient to Jews compared to Gentile Christians. Some anti-Christian Romans further distinguished between Jews and Christians by claiming that Christianity was "apostasy" from Judaism. Celsus, for example, considered Jewish Christians to be hypocrites for claiming that they embraced their Jewish heritage. [78]

Emperor Nero persecuted Christians in Rome, whom he blamed for starting the Great Fire of AD 64. It is possible that Peter and Paul were in Rome and were martyred at this time. Nero was deposed in AD 68, and the persecution of Christians ceased. Under the emperors Vespasian (r. 69–79) and Titus (r. 79–81), Christians were largely ignored by the Roman government. The Emperor Domitian (r. 81–96) authorized a new persecution against the Christians. It was at this time that the Book of Revelation was written by John of Patmos.[79]

References

[edit]- ^ González 1987, p. 37.

- ^ McGrath 2013, p. 14.

- ^ Fredriksen 1999, p. 121.

- ^ Bond 2012, pp. 57–59.

- ^ Schnelle 2020, pp. 58–60.

- ^ Schnelle 2020, pp. 13 & 16.

- ^ MacCulloch 2010, p. 66–69.

- ^ Schnelle 2020, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Schnelle 2020, p. 51.

- ^ MacCulloch 2010, p. 72.

- ^ Schnelle 2020, p. 49.

- ^ González 1987, pp. 33–37.

- ^ Schnelle 2020, pp. 49 & 51–52.

- ^ Fredriksen 1999, pp. 119–121.

- ^ Bond 2012, pp. 62–64.

- ^ Fredriksen 1999, p. 124.

- ^ Bond 2012, p. 63.

- ^ González 1987, p. 38.

- ^ Schnelle 2020, pp. 13–17.

- ^ Schnelle 2020, pp. 18–21 & 25.

- ^ Bond 2012, pp. 42 & 48.

- ^ Bond 2012, pp. 78, 85, 87–89 & 95–96.

- ^ McGrath 2013, p. 6.

- ^ MacCulloch 2010, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Bond 2012, p. 109.

- ^ MacCulloch 2010, pp. 91–95.

- ^ MacCulloch 2010, p. 95.

- ^ Chadwick 1993, p. 13.

- ^ McGrath 2013, p. 7.

- ^ Bond 2012, pp. 38 & 40–41.

- ^ Annals 15.44.3 quoted in Bond (2012, p. 38).

- ^ a b c d McGrath 2013, p. 10.

- ^ McGrath 2013, p. 12.

- ^ Chadwick 1993, pp. 15–16.

- ^ a b McGrath 2013, p. 2.

- ^ Mitchell 2006, pp. 109, 112, 114–115 & 117.

- ^ McGrath 2013, pp. 7–9.

- ^ Hopkins 1998, p. 195.

- ^ Pixner, Bargil (May–June 1990). "The Church of the Apostles found on Mount Zion". Biblical Archaeology Review. Vol. 16, no. 3. Archived from the original on 9 March 2018 – via CenturyOne Foundation.

- ^ a b c d e f Bokenkotter, Thomas (2004). A Concise History of the Catholic Church (Revised and expanded ed.). Doubleday. pp. 19–21. ISBN 978-0-385-50584-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Cross, F. L.; Livingstone, E. A., eds. (2005). "James, St.". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3rd Revised ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 862. doi:10.1093/acref/9780192802903.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3.

- ^ Mitchell 2006, p. 103.

- ^ González 2010, p. 27.

- ^ a b González 2010, pp. 28–29.

- ^ a b Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985.

- ^ a b Eusebius, Church History 3, 5, 3; Epiphanius, Panarion 29,7,7–8; 30, 2, 7; On Weights and Measures 15. On the flight to Pella see: Jonathan Bourgel, "'The Jewish Christians' Move from Jerusalem as a pragmatic choice", in: Dan Jaffé (ed), Studies in Rabbinic Judaism and Early Christianity, (Leyden: Brill, 2010), pp. 107–138 (https://www.academia.edu/4909339/THE_JEWISH_CHRISTIANS_MOVE_FROM_JERUSALEM_AS_A_PRAGMATIC_CHOICE).

- ^ a b P. H. R. van Houwelingen, "Fleeing forward: The departure of Christians from Jerusalem to Pella", Westminster Theological Journal 65 (2003), 181–200.

- ^ González 2010, p. 33.

- ^ Marcus 2006, p. 88.

- ^ St. James the Less Catholic Encyclopedia: "Then we lose sight of James till St. Paul, three years after his conversion (A.D. 37), went up to Jerusalem. ... On the same occasion, the "pillars" of the Church, James, Peter, and John "gave to me (Paul) and Barnabas the right hands of fellowship; that we should go unto the Gentiles, and they unto the circumcision" (Galatians 2:9)."

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cross, F. L.; Livingstone, E. A., eds. (2005). "Paul the Apostle". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3rd Revised ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1243–45. doi:10.1093/acref/9780192802903.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3.

- ^ a b Hodges, Frederick M. (2001). "The Ideal Prepuce in Ancient Greece and Rome: Male Genital Aesthetics and Their Relation to Lipodermos, Circumcision, Foreskin Restoration, and the Kynodesme" (PDF). Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 75 (Fall 2001). Johns Hopkins University Press: 375–405. doi:10.1353/bhm.2001.0119. PMID 11568485. S2CID 29580193. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ a b Rubin, Jody P. (July 1980). "Celsus' Decircumcision Operation: Medical and Historical Implications". Urology. 16 (1). Elsevier: 121–124. doi:10.1016/0090-4295(80)90354-4. PMID 6994325. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ a b Schultheiss, Dirk; Truss, Michael C.; Stief, Christian G.; Jonas, Udo (1998). "Uncircumcision: A Historical Review of Preputial Restoration". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 101 (7). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: 1990–8. doi:10.1097/00006534-199806000-00037. PMID 9623850. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ a b Fredriksen, Paula (2018). When Christians Were Jews: The First Generation. London: Yale University Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0-300-19051-9.

- ^ Kohler, Kaufmann; Hirsch, Emil G.; Jacobs, Joseph; Friedenwald, Aaron; Broydé, Isaac. "Circumcision: In Apocryphal and Rabbinical Literature". Jewish Encyclopedia. Kopelman Foundation. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

Contact with Grecian life, especially at the games of the arena [which involved nudity], made this distinction obnoxious to the Hellenists, or antinationalists; and the consequence was their attempt to appear like the Greeks by epispasm ("making themselves foreskins"; I Macc. i. 15; Josephus, "Ant." xii. 5, § 1; Assumptio Mosis, viii.; I Cor. vii. 18; Tosef., Shab. xv. 9; Yeb. 72a, b; Yer. Peah i. 16b; Yeb. viii. 9a). All the more did the law-observing Jews defy the edict of Antiochus Epiphanes prohibiting circumcision (I Macc. i. 48, 60; ii. 46); and the Jewish women showed their loyalty to the Law, even at the risk of their lives, by themselves circumcising their sons.

- ^ [52][53][54][55][56]

- ^ Neusner, Jacob (1993). Approaches to Ancient Judaism, New Series: Religious and Theological Studies. Scholars Press. p. 149.

Circumcised barbarians, along with any others who revealed the glans penis, were the butt of ribald humor. For Greek art portrays the foreskin, often drawn in meticulous detail, as an emblem of male beauty; and children with congenitally short foreskins were sometimes subjected to a treatment, known as epispasm, that was aimed at elongation.

- ^ [52][53][55][54][58]

- ^ Vana, Liliane (May 2013). Trigano, Shmuel (ed.). "Les lois noaẖides: Une mini-Torah pré-sinaïtique pour l'humanité et pour Israël" [The Noahid Laws: A Pre-Sinaitic Mini-Torah for Humanity and for Israel]. Pardés: Études et culture juives (in French). 52 (2). Paris: Éditions in Press: 211–236. doi:10.3917/parde.052.0211. eISSN 2271-1880. ISBN 978-2-84835-260-2. ISSN 0295-5652 – via Cairn.info.

- ^ Bockmuehl, Markus (January 1995). "The Noachide Commandments and New Testament Ethics: with Special Reference to Acts 15 and Pauline Halakhah". Revue Biblique. 102 (1). Leuven: Peeters Publishers: 72–101. ISSN 0035-0907. JSTOR 44076024.

- ^ a b Fitzmyer, Joseph A. (1998). The Acts of the Apostles: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. The Anchor Yale Bible Commentaries. Vol. 31. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. p. Chapter V. ISBN 978-0-300-13982-2.

- ^ [60][61][62]

- ^ "peri'ah", (Shab. xxx. 6)

- ^ a b c d Black, C. Clifton; Smith, D. Moody; Spivey, Robert A., eds. (2019) [1969]. "Paul: Apostle to the Gentiles". Anatomy of the New Testament (8th ed.). Minneapolis: Fortress Press. pp. 187–226. doi:10.2307/j.ctvcb5b9q.17. ISBN 978-1-5064-5711-6. OCLC 1082543536. S2CID 242771713.

- ^ a b c Klutz, Todd (2002) [2000]. "Part II: Christian Origins and Development – Paul and the Development of Gentile Christianity". In Esler, Philip F. (ed.). The Early Christian World. Routledge Worlds (1st ed.). New York and London: Routledge. pp. 178–190. ISBN 978-1-032-19934-4.

- ^ a b Seifrid, Mark A. (1992). "'Justification by Faith' and The Disposition of Paul's Argument". Justification by Faith: The Origin and Development of a Central Pauline Theme. Novum Testamentum, Supplements. Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 210–211, 246–247. ISBN 978-90-04-09521-2. ISSN 0167-9732.

- ^ [40][51][65][66][67]

- ^ [40][51][65][66][67]

- ^ Dunn, James D. G. (Autumn 1993). Reinhartz, Adele (ed.). "Echoes of Intra-Jewish Polemic in Paul's Letter to the Galatians". Journal of Biblical Literature. 112 (3). Society of Biblical Literature: 459–477. doi:10.2307/3267745. ISSN 0021-9231. JSTOR 3267745.

- ^ Thiessen, Matthew (September 2014). Breytenbach, Cilliers; Thom, Johan (eds.). "Paul's Argument against Gentile Circumcision in Romans 2:17-29". Novum Testamentum. 56 (4). Leiden: Brill Publishers: 373–391. doi:10.1163/15685365-12341488. eISSN 1568-5365. ISSN 0048-1009. JSTOR 24735868.

- ^ [51][65][66][70][71]

- ^ Marcus 2006, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Marcus 2006, pp. 99–102.

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia: Jerusalem (A.D. 71–1099): "Epiphanius (d. 403) says that when the Emperor Hadrian came to Jerusalem in 130 he found the Temple and the whole city destroyed save for a few houses, among them the one where the Apostles had received the Holy Ghost. This house, says Epiphanius, is "in that part of Sion which was spared when the city was destroyed" – therefore in the "upper part ("De mens. et pond.", cap. xiv). From the time of Cyril of Jerusalem, who speaks of "the upper Church of the Apostles, where the Holy Ghost came down upon them" (Catech., ii, 6; P.G., XXXIII), there are abundant witnesses of the place. A great basilica was built over the spot in the fourth century; the crusaders built another church when the older one had been destroyed by Hakim in 1010. It is the famous Coenaculum or Cenacle – now a Moslem shrine – near the Gate of David, and supposed to be David's tomb (Nebi Daud)."; Epiphanius' Weights and Measures at tertullian.org.14: "For this Hadrian..."

- ^ Jewish Encyclopedia: Academies in Palestine

- ^ Annals 15.44 quoted in González (2010, p. 45).

- ^ Edward Kessler (18 February 2010). An Introduction to Jewish-Christian Relations. Cambridge University Press. pp. 45–. ISBN 978-1-139-48730-6.

- ^ González 2010, pp. 44–48.

Sources

[edit]- Bond, Helen K. (2012). The Historical Jesus: A Guide for the Perplexed. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9780567125101.

- Chadwick, Henry (1993). The Early Church. The Penguin History of the Church. Vol. 1 (revised ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0140231994.

- Dunn, James D.G. Jews and Christians: The Parting of the Ways, AD 70 to 135. Pp 33–34. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing (1999). ISBN 0-8028-4498-7.

- Esler, Philip F. The Early Christian World (2nd ed.). Routledge (2017). ISBN 978-1-351-67829-2.

- Fredriksen, Paula (1999). Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews: A Jewish Life and the Emergence of Christianity. Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-76746-0.

- González, Justo L. (1987). A History of Christian Thought. Vol. 1: From the Beginnings to the Council of Chalcedon (revised ed.). Abingdon Press. ISBN 0-687-17182-2.

- González, Justo L. (2010). The Story of Christianity. Vol. 1 The Early Church to the Dawn of the Reformation (revised and updated ed.). HarperCollins. ISBN 9780061855887.

- Hopkins, Keith (1998). "Christian Number and Its Implications". Journal of Early Christian Studies. 6 (2). Johns Hopkins University Press: 185–226. doi:10.1353/earl.1998.0035. ISSN 1086-3184. Project MUSE 9960.

- Klutz, Todd (2000). "Paul and the Development of Gentile Christianity". In Esler, Philip F. (ed.). The Early Christian World. Routledge Worlds. Routledge. pp. 178–190. ISBN 9781032199344.

- MacCulloch, Diarmaid (2010). Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-1-101-18999-3.

- Marcus, Joel (2006). "Jewish Christianity". In Mitchell, Margaret M.; Young, Frances M. (eds.). The Cambridge History of Christianity. Vol. 1: Origins to Constantine. Cambridge University Press. pp. 87–102. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521812399. ISBN 9781139054836.

- Mitchell, Margaret M. (2006). "Gentile Christianity". In Mitchell, Margaret M.; Young, Frances M. (eds.). The Cambridge History of Christianity. Vol. 1: Origins to Constantine. Cambridge University Press. pp. 103–124. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521812399. ISBN 9781139054836.

- McGrath, Alister (2013). Christian History: An Introduction. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781118337806.

- Schnelle, Udo (2020). The First One Hundred Years of Christianity: An Introduction to Its History, Literature, and Development. Translated by Thompson, James W. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic. ISBN 978-1-4934-2242-5.

- Seifrid, Mark A. (1992). Justification by Faith: The Origin and Development of a Central Pauline Theme. Novum Testamentum, Supplements. Leiden: Brill Publishers. ISBN 90-04-09521-7. ISSN 0167-9732.

- Mitchell, Margaret M.; Young, Frances M., eds. (2006). The Cambridge History of Christianity. Vol. 1: Origins to Constantine. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521812399. ISBN 9781139054836.

Further reading

[edit]- Dan Jaffe (ed), Studies in Rabbinic Judaism and Early Christianity, (Leyden: Brill, 2010).