User:Macrophyseter/sandbox1

| Great white shark Temporal range: Miocene to Recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Subdivision: | Selachimorpha |

| Order: | Lamniformes |

| Family: | Lamnidae |

| Genus: | Carcharodon A. Smith, 1838 |

| Species: | C. carcharias

|

| Binomial name | |

| Carcharodon carcharias | |

| |

| Global range as of 2010 | |

| Synonyms | |

|

List of synonyms

| |

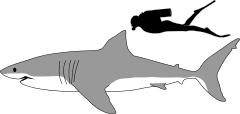

The great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), also known as the great white, white shark or white pointer, is a species of large mackerel shark which can be found in the coastal surface waters of all the major oceans. The great white shark is notable for its size, with larger female individuals growing to 6.1 m (20 ft) in length and 1,905 kg (4,200 lb) in weight at maturity.[3][4][5] However, most are smaller; males measure 3.4 to 4.0 m (11 to 13 ft), and females measure 4.6 to 4.9 m (15 to 16 ft) on average.[5][6] According to a 2014 study, the lifespan of great white sharks is estimated to be as long as 70 years or more, well above previous estimates,[7] making it one of the longest lived cartilaginous fish currently known.[8] According to the same study, male great white sharks take 26 years to reach sexual maturity, while the females take 33 years to be ready to produce offspring.[9] Great white sharks can swim at speeds of over 56 km/h (35 mph),[10] and can swim to depths of 1,200 m (3,900 ft).[11]

The great white shark has no known natural predators other than, on very rare occasions, the killer whale.[12] The great white shark is arguably the world's largest known extant macropredatory fish, and is one of the primary predators of marine mammals. It is also known to prey upon a variety of other marine animals, including fish and seabirds. It is the only known surviving species of its genus Carcharodon, and is responsible for more recorded human bite incidents than any other shark.[13][14]

The species faces numerous ecological challenges which has resulted in international protection. The IUCN lists the great white shark as a vulnerable species,[2] and it is included in Appendix II of CITES.[15] It is also protected by several national governments such as Australia (as of 2018).[16]

The novel Jaws by Peter Benchley and its subsequent film adaptation by Steven Spielberg depicted the great white shark as a "ferocious man eater". Humans are not the preferred prey of the great white shark,[17] but the great white is nevertheless responsible for the largest number of reported and identified fatal unprovoked shark attacks on humans.[18]

Etymology[edit]

The English name 'white shark' and its Australian variant 'white pointer'[19] is thought to have come from the shark's stark white underside, a characteristic feature most noticeable in beached sharks lying upside down with their bellies exposed.[20] Colloquial use favours the name 'great white shark', with 'great' perhaps stressing the size and prowess of the species,[21] and "white shark" having historically been used to describe the much smaller oceanic white-tipped shark, later referred to for a time as the "lesser white shark". Most scientists prefer 'white shark', as the name "lesser white shark" is no longer used,[21] while some use 'white shark' to refer to all members of the Lamnidae.[22]

The scientific genus name Carcharodon literally means "jagged tooth", a reference to the large serrations that appear in the shark's teeth. It is a portmanteau of two Ancient Greek words: the prefix carchar- is derived from κάρχαρος (kárkharos), which means "jagged" or "sharp". The suffix -odon is a romanization of ὀδών (odṓn), a which translates to "tooth". The specific name carcharias is a Latinization of καρχαρίας (karkharías), the Ancient Greek word for shark.[23] The great white shark was one of the species originally described by Carl Linnaeus in his 1758 10th edition of Systema Naturae, in which it was identified as an amphibian and assigned the scientific name Squalus carcharias, Squalus being the genus that he placed all sharks in.[24] By the 1810s, it was recognized that the shark should be placed in a new genus, but it was not until 1838 when Sir Andrew Smith coined the name Carcharodon as the new genus.[25]

There have been a few attempts to describe and classify the great white before Linnaeus. One of its earliest mentions in literature as a distinct type of animal appears in Pierre Belon's 1553 book De aquatilibus duo, cum eiconibus ad vivam ipsorum effigiem quoad ejus fieri potuit, ad amplissimum cardinalem Castilioneum. In it, he illustrated and described the shark under the name Canis carcharias based on the jagged nature of its teeth and its alleged similarities with dogs.[a] Another name used for the great white around this time was Lamia, first coined by Guillaume Rondelet in his 1554 book Libri de Piscibus Marinis, who also identified it as the fish that swallowed the prophet Jonah in biblical texts.[26] Linnaeus recognized both names as previous classifications.[24]

Taxonomy and evolution[edit]

The great white is the sole recognized extant species in the genus Carcharodon, and is one of five extant species belonging to the family Lamnidae.[23] Other members of this family include the mako sharks, porbeagle, and salmon shark. The family belongs to the Lamniformes, the order of mackerel sharks.[22]

Phylogeny[edit]

| Topology A with cytochrome b molecular clock by Martin (1996) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| Topology B |

|---|

Mitochondrial clades and genetic history[edit]

The great white shark appears to maintain consistent gene flow in nuclear DNA between all inhabited oceans, suggesting that the species likely represents a singular population at the global scale. There nevertheless exists significant divergence between groups in mitochondrial DNA, which is passed exclusively from the mother, and consequentially metapopulations at the local scale. This is likely due to an instinctive tendency for females to remain in or return to their birthplace, while males are wide-roaming. Other factors may include isolation by distance, founder effects, infrequent long-distance dispersal, and vicariance. Three major mitochondrial clades are known:

- Indo-Pacific, representing populations in the northeastern Pacific, Australia[b], Oceania, and the Mediterranean Sea

- Atlantic, endemic to the Atlantic Ocean, South Africa, and southern Australia[c]

- South African haplotype D (SAHapD), which is isolated to South Africa

| mtDNA CR molecular clocks in great white shark populations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Molecular clocks indicate that divergence of these clades occurred hundreds of thousands to millions of years ago, although there is no agreement on exact timing. Clocks calibrated by Andreotti et al. (2016) using vicariant geological events[e] estimated that the Indo-Pacific and Atlantic clades diverged between 2.58-4.17 mya, while the Atlantic and SAHapD clades diverged between 420-680 kya. An alternative clock calibrated by Leone et al. (2020) using alleged earliest fossils dated to ~11 mya[d] estimated divergence times between the Indo-Pacific clade and the Atlantic and SAHapD clades at 11.13 mya. The Atlantic clade has significantly lower genetic diversity than the Indo-Pacific clade. This may have arose via the founder effect, which implies the former originated from Indo-Pacific migrants. Diversity in South Africa is even lower; the additional occurrence of at least two distinct clades points to repeat bottlenecks and re-colonizations following climate change cycles.

The existence of an Indo-Pacific population in the Mediterranean Sea, thousands of miles from the clade's typical range, is the result of a long-distance founder event. One hypothesis for this occurrent is the antipodean dispersal hypothesis, proposed by Gubili et al. (2010). It postulates that the population originated as a group of Australian or New Zealander sharks that accidently wandered into the Mediterranean through an unusually powerful Agulhas Current during the Pleistocene. The proposed time of Mediterranean divergence was around 450 kya, which coincided with a period when the current's westward eddies may have traveled farther north due to climate instability. A competing hypothesis is the Pliocene colonization hypothesis, postulated by Leon et al. (2020). It suggests that the Mediterranean population instead diverged around 3.23 mya, and originated from a Pacific population that migrated into the Atlantic through the Central American Seaway.

Fossil history[edit]

Origins[edit]

The great white shark first unambiguously appears in the fossil record in the Pacific basin about 5.3 mya at the beginning of the Pliocene. Although there are few reports of fossils dated as early as 16 mya, their validity is generally doubted as mislabeled or misidentified.[f] Like all sharks, the great white's skeleton is made primarily of soft cartilage that does not preserve well. The overwhelming majority of fossils as a result are teeth. Nevertheless, paleontologists have confidently traced the emergence of the great white shark and its immediate ancestry to a large extinct shark known as Carcharodon hastalis (alternatively Cosmopolitodus hastalis[g]). This species unambiguously appeared worldwide during the Early Miocene (~23 mya) and whose teeth were alike to the modern great white shark's, except that the cutting edges were non-serrated. C. hastalis occupied a middle to high trophic position in its ecosystems, with a distinct narrow-toothed form that probably specialized in fish and a broad-toothed form that fed on marine mammals.[h]

Around 8 mya, a Pacific stock of C. hastalis evolved into C. hubbelli. This divergent lineage, sometimes described as a chronospecies, was characterized by a gradual development of serrations over the next few million years. They were initially fine and sparse but a mosaic of fossils throughout the Pacific basin[i] document an increase in quantity and coarseness over time, eventually becoming fully serrated as the great white shark's by 5.3 mya. Serrations are more effective at cutting prey than non-serrated edges, facilitating further specialization towards a mammal diet. The ecological circumstances for this innovation may depend on which C. hastalis form was the immediate ancestor of C. hubbelli, which remains uncertain. A narrow-toothed progenitor would imply serrations evolved to accommodate a change in diet, while a broad-toothed ancestor suggests development as a competitive advantage. The great white shark dispersed as soon as it emerged, with fossils in the Mediterranean, North Sea Basin, and South Africa occurring as early as 5.3-5 mya. Colonization of the northwestern Atlantic may have been delayed, with fossils absent until 3.2 mya.

Current paleontological convention holds that C. hastalis evolved from Macrorhizodus praecursor, another large shark that may have hunted both fish and marine mammals and inhabited the ancient Tethys Sea during the Eocene (~50-40 mya).

The white shark line beyond C. hastalis is less certain. Fossil lamnids close to the divergence time with the mako sharks are fraught with overlapping traits that has created uncertainty as to which forms belongs to which lineage. This is exacerbated by poor stratigraphic record-keeping of many of these fossils, and a general lack of scientific interest in the topic.

Current paleontological convention holds that C. hastalis evolved from Macrorhizodus praecursor, another large shark that may have hunted both fish and marine mammals and inhabited the ancient Tethys Sea during the Eocene (~50-40 mya). The ancestor of this species was probably a primitive mako-like shark of unclear identity. It has suggested that it may have been Isurolamna inflata

Paleoecology[edit]

Anatomy and appearence[edit]

Size[edit]

Jaws and teeth[edit]

Physiology[edit]

Ecology and behavior[edit]

Relationship with humans[edit]

Human interactions[edit]

"In California, peaceful close encounters between beachgoers and juvenile great whites occur on a near-daily basis."

Reasons for incidents[edit]

Shark tourism[edit]

Conservation[edit]

Population[edit]

Threats[edit]

Shark culling[edit]

See also[edit]

Books[edit]

- The Devil's Teeth by Susan Casey.

- Close to Shore by Michael Capuzzo about the Jersey Shore shark attacks of 1916.

- Twelve Days of Terror by Richard Fernicola about the same events.

Notes[edit]

- ^ During Belon's time, sharks were called "sea dogs".[26]

- ^ Locally known as the East Australasian population

- ^ Locally known as the Southern-western population

- ^ a b This is inconsistent with contemporary paleontological consensus of C. carcharias origins, which Leone et al. (2020) overlooked. Reports of fossils predating the C. hubbelli-C. carcharias transition between 8-5 mya are dubious and likely artifacts of mislabeling or misidentifications of similar taxa like megalodon.[29]

- ^ a b Closure of the Central American Seaway ~3.5 mya (which severed communication between the east Pacific and Atlantic) and ascent of the Sunda and Sahul shelves ~5 mya (which restricted communication between Pacific and Indian oceans) respectively.

- ^ For example, several Miocene fossils initially identified as great white sharks were later found to be juvenile forms of the contemporaneous megalodon.

- ^ The genus name remains subject to esoteric debate that does not significantly affect the consensus on the great white shark's origins in C. hastalis. The debate primarily centers on whether the appearance of serrations is sufficient to delineate separate genera, and whether a form traditionally attributed to C. hastalis is actually a separate species called C. plicatilis. The latter's recognition is necessary for Cosmopolitodus be a natural grouping. This should not be confused with the archaic name Isurus hastalis, which is no longer recognized by paleontologists.

- ^ The relationship between the two forms is fiercely debated. Some paleontologists consider them to be age or sex-related differences, while other argue that the broad-toothed form represents a separate species, C. plicatilis. Neither hypothesis has been tested through phylogenetic analysis.

- ^ California, Peru, Chile, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand

References[edit]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

CAwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Fergusson, I.; Compagno, L.J.V.; Marks, M. (2009). "Carcharodon carcharias". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2009: e.T3855A10133872. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2009-2.RLTS.T3855A10133872.en. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ^ "Great white sharks: 10 myths debunked". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ^ Carpenter, K. "Carcharodon carcharias". FishBase.org. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ^ a b Viegas, Jennifer. "Largest Great White Shark Don't Outweigh Whales, but They Hold Their Own". Discovery Channel. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- ^ Parrish, M. "How Big are Great White Sharks?". Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History Ocean Portal. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ^ "Carcharodon carcharias". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ^ "New study finds extreme longevity in white sharks". Science Daily. 9 January 2014.

- ^ Ghose, Tia (19 February 2015). "Great White Sharks Are Late Bloomers". LiveScience.com.

- ^ Wright, Bruce A. (2007) Alaska's Great White Sharks. Lulu.com. p. 27. ISBN 0-615-15595-2.

- ^ Thomas, Pete (5 April 2010). "Great white shark amazes scientists with 4000-foot dive into abyss". GrindTV. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012.

- ^ Currents of Contrast: Life in Southern Africa's Two Oceans. Struik. 2005. pp. 31–. ISBN 978-1-77007-086-8.

- ^ Knickle, Craig. "Tiger Shark". Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department. Archived from the original on 7 July 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2009.

- ^ "ISAF Statistics on Attacking Species of Shark". Florida Museum of Natural History University of Florida. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Carcharodon carcharias". UNEP-WCMC Species Database: CITES-Listed Species On the World Wide Web. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- ^ Government of Australia Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (2013). Recovery Plan for the White Shark (Carcharodon carcharias) (Report).

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hile, Jennifer (23 January 2004). "Great White Shark Attacks: Defanging the Myths". Marine Biology. National Geographic. Archived from the original on 26 April 2009. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ ISAF Statistics on Attacking Species of Shark

- ^ "Common names of Carcharodon carcharias". FishBase. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ Martins, C.; Knickle, C. (2018). "Carcharodon carcharias". Florida Museum. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ a b Martin, R. A. "White Shark or Great White Shark?". Elasmo Research. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Family Lamnidae – Mackerel sharks or white shark". FishBase. Archived from the original on 10 November 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Carcharodon carcharias, Great white shark". FishBase. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ a b Linnaeus, C (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata (in Latin). Vol. 1. Holmiae (Laurentii Salvii). p. 235. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.542. Archived from the original on 25 March 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ Jordan, D. S. (1925). "The Generic Name of the Great White Shark, Squalus carcharias L.". Copeia. 140 (1925): 17–20. doi:10.2307/1435586. JSTOR 1435586.

- ^ a b Costantino, G. (18 August 2014). "Sharks Were Once Called Sea Dogs, And Other Little-Known Facts". Smithsonain.com. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 1 July 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ^ a

- ^ a

- ^ https://natuurtijdschriften.nl/pub/677433/

External links[edit]

- Great White Shark: Fact File from National Geographic

- Photo Gallery: Great White Sharks from National Geographic

- ARKive – Images and movies of the great white shark, Carcharodon carcharias

- Great white shark from BBC Nature

- Great white shark from the World Wildlife Fund

- In-depth article: "Shark's Super Senses" from the PBS Ocean Adventures site

- Are great whites descended from mega-sharks? from LiveScience

- "Great White Sharks – The Truth" by documentary maker Carly Maple – Australian focus

- White Shark Biological Profile from the Florida Museum of Natural History

- Leviathans may battle in remote depths from the Los Angeles Times

great white shark Category:Ovoviviparous fish Category:Scavengers Category:Cosmopolitan fish Category:Extant Miocene first appearances great white shark Category:Articles containing video clips Category:Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus