User:Marcelus/sandbox7

Jews and the Polish government[edit]

Lack of international effort to aid Jews resulted in political uproar on the part of the Polish government in exile residing in Great Britain. The government often publicly expressed outrage at German mass murders of Jews. In 1942, the Directorate of Civil Resistance, part of the Polish Underground State, issued the following declaration based on reports by the Polish underground:[1]

For nearly a year now, in addition to the tragedy of the Polish people, which is being slaughtered by the enemy, our country has been the scene of a terrible, planned massacre of the Jews. This mass murder has no parallel in the annals of mankind; compared to it, the most infamous atrocities known to history pale into insignificance. Unable to act against this situation, we, in the name of the entire Polish people, protest the crime being perpetrated against the Jews; all political and public organizations join in this protest.[1]

The Polish government was the first to inform the Western Allies about the Holocaust, although early reports were often met with disbelief, even by Jewish leaders themselves, and then, for much longer, by Western powers.[2][3][4][5][6]

The Polish underground and also the government-in-exile were involved in gathering information about the terror in occupied Poland and passing this information to the Western allies and their public. Among these, reports of particular terror affecting the Jewish population played an important role. With the start of the mass extermination of Jews in central Poland in late 1941 and early 1942, there was a need, primarily among Jewish leaders, to alert the world of the genocide taking place.

The Oneg Shabbat group, headed by Emanuel Ringelblum, prepared a report in March 1942, written by Hersz Wasser, based on Szlama Ber Winer's account of the Chełmno death camp. The report became part of a study written on March 25, 1942, by Antoni Szymanowski, an employee of the Bureau of Information and Propaganda of the Home Army Headquarters, under the title Mass Executions of Jews in the Koło County. Szymanowski's work was sent to London on June 23, 1942, along with information about the start of the deportation of Jews from the Lublin Ghetto. The second Oneg Shabbat report was written in April 1942 it depicted the entirety of German anti-Jewish activity since the beginning of the war, its author was probably Eliahu Gutkowski. It was also transmitted to London by an unknown route. The third Oneg Shabbat report was Gehenna of Polish Jews under German Occupation, written in June 1942, a synthetic description and compilation of executions and deportations of Jewish people from all over Poland. This report was probably forwarded to London in July 1942. The last Oneg Shabbat report was The Liquidation of Jewish Warsaw, written on November 15, 1942, concerning the course of the liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto and the functioning of the Treblinka camp. This report reached London in January 1943.

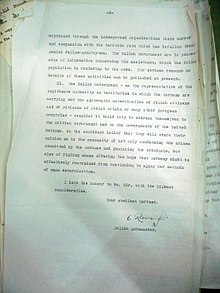

So-called Raczkiewicz's note of 9/10 December 1942 was the first official document informing about the Holocaust.[7]

Pilecki[edit]

Witold Pilecki was a member of the Polish Armia Krajowa (AK) resistance, and the only person who volunteered to be imprisoned in Auschwitz. As an agent of the underground intelligence, he began sending numerous reports about the camp and genocide to the Polish resistance headquarters in Warsaw through the resistance network he organized in Auschwitz. In March 1941, Pilecki's reports were being forwarded via the Polish resistance to the British government in London, but the British government refused AK reports on atrocities as being gross exaggerations and propaganda of the Polish government.

Karski[edit]

Similarly, in 1942, Jan Karski, who had been serving as a courier between the Polish underground and the Polish government in exile, was smuggled into the Warsaw Ghetto and reported to the Polish, British and American governments on the terrible situation of the Jews in Poland, in particular the destruction of the ghetto.[8] He met with Polish politicians in exile, including the prime minister, as well as members of political parties such as the Polish Socialist Party, National Party, Labor Party, People's Party, Jewish Bund and Poalei Zion. He also spoke to Anthony Eden, the British foreign secretary, and included a detailed statement on what he had seen in Warsaw and Bełżec.

In 1943 in London, Karski met the well-known journalist Arthur Koestler. He then traveled to the United States and reported to U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt. In July 1943, Jan Karski again personally reported to Roosevelt about the plight of Polish Jews, but the president "interrupted and asked the Polish emissary about the situation of... horses" in Poland.[9][10] He also met with many other government and civic leaders in the United States, including Felix Frankfurter, Cordell Hull, William J. Donovan, and Stephen Wise. Karski also presented his report to the news media, bishops of various denominations (including Cardinal Samuel Stritch), members of the Hollywood film industry, and artists, but without success. Many of those he spoke to did not believe him and again supposed that his testimony was much exaggerated or was propaganda from the Polish government in exile.

Delegation, ŻOB and Żegota[edit]

The supreme political body of the underground government within Poland was the Delegatura. There were no Jewish representatives in it.[11] Delegatura financed and sponsored Żegota, the organization for help to the Polish Jews – run jointly by Jews and non-Jews.[12] Since 1942 Żegota was granted by Delegatura nearly 29 million zlotys (over $5 million; or, 13.56 times as much,[13] in today's funds) for the relief payments to thousands of extended Jewish families in Poland.[14] The Home Army also provided assistance including arms, explosives and other supplies to Jewish Combat Organization (ŻOB), particularly from 1942 onwards.[15] The interim government transmitted messages to the West from the Jewish underground, and gave support to their requests for retaliation on German targets if the atrocities are not stopped – a request that was dismissed by the Allied governments.[16] The Polish government also tried, without much success, to increase the chances of Polish refugees finding a safe haven in neutral countries and to prevent deportations of escaping Jews back to Nazi-occupied Poland.[16]

Sławik[edit]

Polish Delegate of the Government in Exile residing in Hungary, diplomat Henryk Sławik known as the Polish Wallenberg,[17] helped rescue over 30,000 refugees including 5,000 Polish Jews in Budapest, by giving them false Polish passports as Christians.[18] He founded an orphanage for Jewish children officially named School for Children of Polish Officers in Vác.[19][20]

National Council and Jewish section[edit]

Polish Jews were represented, as the only minority, by two members on the National Council, a 20-30 member body that served as a quasi-parliament to the government in exile: Ignacy Schwarzbart and Szmul Zygielbojm.[21] Also, in 1943 a Jewish affairs section of the Underground State was set up by the Government Delegation for Poland; it was headed by Witold Bieńkowski and Władysław Bartoszewski.[1] Its purpose was to organize efforts concerning the Polish Jewish population, to coordinate with Żegota, and to prepare documentation about the fate of the Jews for the government in London.[1] Regrettably, the great number of Polish Jews had been killed already even before the Government-in-exile fully realized the totality of the Final Solution.[21] According to David Engel and Dariusz Stola, the government-in-exile concerned itself with the fate of Polish people in general, the re-recreation of the independent Polish state, and with establishing itself as an equal partner amongst the Allied forces.[22][6][23] On top of its relative weakness, the government in exile was subject to the scrutiny of the West, in particular, American and British Jews reluctant to criticize their own governments for inaction in regard to saving their fellow Jews.[24]

Szmalcowniks punishment[edit]

The Polish government and its underground representatives at home issued declarations that people acting against the Jews (blackmailers and others) would be punished by death. General Władysław Sikorski, the Prime Minister and Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Armed Forces, signed a decree calling upon the Polish population to extend aid to the persecuted Jews; including the following stern warning.[25]

Any direct and indirect complicity in the German criminal actions is the most serious offence against Poland. Any Pole who collaborates in their acts of murder, whether by extortion, informing on Jews, or by exploiting their terrible plight or participating in acts of robbery, is committing a major crime against the laws of the Polish Republic.

— Warsaw, May 1943 [25]

According to Michael C. Steinlauf, before the Warsaw Ghetto uprising in 1943, Sikorski's appeals to Poles to help Jews accompanied his communiques only on rare occasions.[26] Steinlauf points out that in one speech made in London, he was promising equal rights for Jews after the war, but the promise was omitted from the printed version of the speech for no reason.[26] According to David Engel, the loyalty of Polish Jews to Poland and Polish interests was held in doubt by some members of the exiled government,[6][23] leading to political tensions.[27] For example, the Jewish Agency refused to give support to Polish demand for the return of Lwów and Wilno to Poland.[28] Overall, as Stola notes, Polish government was just as unprepared to deal with the Holocaust as were the other Allied governments, and that the government's hesitancy in appeals to the general population to aid the Jews diminished only after reports of the Holocaust became more wide spread.[29]

Zygielbojm[edit]

Szmul Zygielbojm, a Jewish member of the National Council of the Polish government in exile, committed suicide in May 1943, in London, in protest against the indifference of the Allied governments toward the destruction of the Jewish people, and the failure of the Polish government to rouse public opinion commensurate with the scale of the tragedy befalling Polish Jews.[30]

Courts[edit]

Poland, with its unique underground state, was the only country in occupied Europe to have an extensive, underground justice system.[32] These clandestine courts operated with attention to due process (although limited by circumstances), so it could take months to get a death sentence passed.[32] However, Prekerowa notes that the death sentences by non-military courts only began to be issued in September 1943, which meant that blackmailers were able to operate for some time already since the first Nazi anti-Jewish measures of 1940.[33] Overall, it took the Polish underground until late 1942 to legislate and organize non-military courts which were authorized to pass death sentences for civilian crimes, such as non-treasonous collaboration, extortion and blackmail.[32] According to Joseph Kermish from Israel, among the thousands of collaborators sentenced to death by the Underground courts and executed by the Polish resistance fighters who risked death carrying out these verdicts,[33] few were explicitly blackmailers or informers who had persecuted Jews. This, according to Kermish, led to increasing boldness of some of the blackmailers in their criminal activities.[34] Marek Jan Chodakiewicz writes that a number of Polish Jews were executed for denouncing other Jews. He notes that since Nazi informers often denounced members of the underground as well as Jews in hiding, the charge of collaboration was a general one and sentences passed were for cumulative crimes.[35]

Jews in Home Army ranks[edit]

The Home Army units under the command of officers from left-wing Sanacja, the Polish Socialist Party as well as the centrist Democratic Party welcomed Jewish fighters to serve with Poles without problems stemming from their ethnic identity.[a] However, some rightist units of the Armia Krajowa excluded Jews. Similarly, some members of the Delegate's Bureau saw Jews and ethnic Poles as separate entities.[37] Historian Israel Gutman has noted that AK leader Stefan Rowecki advocated the abandonment of the long-range considerations of the underground and the launch of an all-out uprising should the Germans undertake a campaign of extermination against ethnic Poles, but that no such plan existed while the extermination of Jewish Polish citizens was under way.[38] On the other hand, the pre-war Polish government armed and trained Jewish paramilitary groups such as Lehi and – while in exile – accepted thousands of Polish Jewish fighters into Anders Army including leaders such as Menachem Begin. The policy of support continued throughout the war with the Jewish Combat Organization and the Jewish Military Union forming an integral part of the Polish resistance.[39]

- ^ a b c d Cite error: The named reference

Delwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

ASwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Piotrowski118was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Piotrowski117was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

DEwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

en1was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Długołęcki 2022, p. XIV.

- ^ Yad Vashem (2013). "Jan Karski, Poland". The Righteous Among the Nations. The Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority. Archived from the original on 25 April 2013 – via Internet Archive.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Cite error: The named reference

varietywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

fzp.net.plwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

google25was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

google26was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

dollartimeswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

google27was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Stola 2003, p. 91.

- ^ a b Stola 2003, p. 87.

- ^ Grzegorz Łubczyk, "Henryk Slawik – the Polish Wallenberg". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 23 September 2004. Trybuna 120 (3717), 24 May 2002.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Unsung Herowas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Premiera filmu "Henryk Sławik – Polski Wallenberg."". Archived from the original on 2 September 2007. Retrieved 2 September 2007. Archiwum działalności Prezydenta RP w latach 1997–2005. BIP.

- ^ Maria Zawadzka, "Righteous Among the Nations: Henryk Sławik and József Antall." Museum of the History of Polish Jews. Warsaw, 7 October 2010. See also: "The Sławik family" (ibidem). Accessed 3 September 2011.

- ^ a b Stola 2003, p. 88.

- ^ Stola 2003, p. 86.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

en2was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

google28was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

yadvashem29was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Michael C. Steinlauf p. 38was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

google30was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

google29was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Stola 2003, p. 90, 93.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

google31was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

ChM2008was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

Salmwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

per7576was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Kermishwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

google32was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

huji33was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

google34was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

google35was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

FocusPlwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).

- ^ As noted by Joshua D. Zimmerman, many negative stereotypes about the Home Army among the Jews came from reading postwar literature on the subject, and not from personal experience.[36]

- Długołęcki, Piotr (2022). "Preface". In Długołęcki, Piotr (ed.). Confronting the Holocaust. Documents on the Polish Government-in-Exile’s Policy Concerning Jews 1939–1945 (PDF). Warsaw.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)