User:Mr. Ibrahem/Gandhi

Principles, practices, and beliefs[edit]

Gandhi's statements, letters and life have attracted much political and scholarly analysis of his principles, practices and beliefs, including what influenced him. Some writers present him as a paragon of ethical living and pacifism, while others present him as a more complex, contradictory and evolving character influenced by his culture and circumstances.[1][2]

Influences[edit]

Gandhi grew up in a Hindu and Jain religious atmosphere in his native Gujarat, which were his primary influences, but he was also influenced by his personal reflections and literature of Hindu Bhakti saints, Advaita Vedanta, Islam, Buddhism, Christianity, and thinkers such as Tolstoy, Ruskin and Thoreau.[3][4] At age 57 he declared himself to be Advaitist Hindu in his religious persuasion, but added that he supported Dvaitist viewpoints and religious pluralism.[5][6][7]

Gandhi was influenced by his devout Vaishnava Hindu mother, the regional Hindu temples and saint tradition which co-existed with Jain tradition in Gujarat.[3][8] Historian R.B. Cribb states that Gandhi's thought evolved over time, with his early ideas becoming the core or scaffolding for his mature philosophy. He committed himself early to truthfulness, temperance, chastity, and vegetarianism.[9]

Gandhi's London lifestyle incorporated the values he had grown up with. When he returned to India in 1891, his outlook was parochial and he could not make a living as a lawyer. This challenged his belief that practicality and morality necessarily coincided. By moving in 1893 to South Africa he found a solution to this problem and developed the central concepts of his mature philosophy.[10]

According to Bhikhu Parekh, three books that influenced Gandhi most in South Africa were William Salter's Ethical Religion (1889); Henry David Thoreau's On the Duty of Civil Disobedience (1849); and Leo Tolstoy's The Kingdom of God Is Within You (1894). Ruskin inspired his decision to live an austere life on a commune, at first on the Phoenix Farm in Natal and then on the Tolstoy Farm just outside Johannesburg, South Africa.[11] The most profound influence on Gandhi were those from Hinduism, Christianity and Jainism, states Parekh, with his thoughts "in harmony with the classical Indian traditions, specially the Advaita or monistic tradition".[12]

According to Indira Carr and others, Gandhi was influenced by Vaishnavism, Jainism and Advaita Vedanta.[13][14] Balkrishna Gokhale states that Gandhi was influenced by Hinduism and Jainism, and his studies of Sermon on the Mount of Christianity, Ruskin and Tolstoy.[15]

Additional theories of possible influences on Gandhi have been proposed. For example, in 1935, N. A. Toothi stated that Gandhi was influenced by the reforms and teachings of the Swaminarayan tradition of Hinduism. According to Raymond Williams, Toothi may have overlooked the influence of the Jain community, and adds close parallels do exist in programs of social reform in the Swaminarayan tradition and those of Gandhi, based on "nonviolence, truth-telling, cleanliness, temperance and upliftment of the masses."[16][17] Historian Howard states the culture of Gujarat influenced Gandhi and his methods.[18]

Leo Tolstoy[edit]

Along with the book mentioned above, in 1908 Leo Tolstoy wrote A Letter to a Hindu, which said that only by using love as a weapon through passive resistance could the Indian people overthrow colonial rule. In 1909, Gandhi wrote to Tolstoy seeking advice and permission to republish A Letter to a Hindu in Gujarati. Tolstoy responded and the two continued a correspondence until Tolstoy's death in 1910 (Tolstoy's last letter was to Gandhi).[19] The letters concern practical and theological applications of nonviolence.[20] Gandhi saw himself a disciple of Tolstoy, for they agreed regarding opposition to state authority and colonialism; both hated violence and preached non-resistance. However, they differed sharply on political strategy. Gandhi called for political involvement; he was a nationalist and was prepared to use nonviolent force. He was also willing to compromise.[21] It was at Tolstoy Farm where Gandhi and Hermann Kallenbach systematically trained their disciples in the philosophy of nonviolence.[22]

Shrimad Rajchandra[edit]

Gandhi credited Shrimad Rajchandra, a poet and Jain philosopher, as his influential counsellor. In Modern Review, June 1930, Gandhi wrote about their first encounter in 1891 at Dr. P.J. Mehta's residence in Bombay. He was introduced to Shrimad by Dr. Pranjivan Mehta.[23] Gandhi exchanged letters with Rajchandra when he was in South Africa, referring to him as Kavi (literally, "poet"). In 1930, Gandhi wrote, "Such was the man who captivated my heart in religious matters as no other man ever has till now."[24] 'I have said elsewhere that in moulding my inner life Tolstoy and Ruskin vied with Kavi. But Kavi's influence was undoubtedly deeper if only because I had come in closest personal touch with him.'[25]

Gandhi, in his autobiography, called Rajchandra his "guide and helper" and his "refuge [...] in moments of spiritual crisis". He had advised Gandhi to be patient and to study Hinduism deeply.[26][27][28]

Religious texts[edit]

During his stay in South Africa, along with scriptures and philosophical texts of Hinduism and other Indian religions, Gandhi read translated texts of Christianity such as the Bible, and Islam such as the Quran.[29] A Quaker mission in South Africa attempted to convert him to Christianity. Gandhi joined them in their prayers and debated Christian theology with them, but refused conversion stating he did not accept the theology therein or that Christ was the only son of God.[29][30][31]

His comparative studies of religions and interaction with scholars, led him to respect all religions as well as become concerned about imperfections in all of them and frequent misinterpretations.[29] Gandhi grew fond of Hinduism, and referred to the Bhagavad Gita as his spiritual dictionary and greatest single influence on his life.[29][32][33] Later, Gandhi translated the Gita into Gujarati in 1930.[34]

Sufism[edit]

Gandhi was acquainted with Sufi Islam's Chishti Order during his stay in South Africa. He attended Khanqah gatherings there at Riverside. According to Margaret Chatterjee, Gandhi as a Vaishnava Hindu shared values such as humility, devotion and brotherhood for the poor that is also found in Sufism.[35][36] Winston Churchill also compared Gandhi to a Sufi fakir.[37]

On wars and nonviolence[edit]

Support for wars[edit]

Gandhi participated in forming the Indian Ambulance Corps in the South African war against the Boers, on the British side in 1899.[38] Both the Dutch settlers called Boers and the imperial British at that time discriminated against the coloured races they considered as inferior, and Gandhi later wrote about his conflicted beliefs during the Boer war. He stated that "when the war was declared, my personal sympathies were all with the Boers, but my loyalty to the British rule drove me to participation with the British in that war. I felt that, if I demanded rights as a British citizen, it was also my duty, as such to participate in the defence of the British Empire, so I collected together as many comrades as possible, and with very great difficulty got their services accepted as an ambulance corps."[39]

During World War I (1914–1918), nearing the age of 50, Gandhi supported the British and its allied forces by recruiting Indians to join the British army, expanding the Indian contingent from about 100,000 to over 1.1 million.[40][38] He encouraged Indian people to fight on one side of the war in Europe and Africa at the cost of their lives.[38] Pacifists criticised and questioned Gandhi, who defended these practices by stating, according to Sankar Ghose, "it would be madness for me to sever my connection with the society to which I belong".[38] According to Keith Robbins, the recruitment effort was in part motivated by the British promise to reciprocate the help with swaraj (self-government) to Indians after the end of World War I.[41] After the war, the British government offered minor reforms instead, which disappointed Gandhi.[40] He launched his satyagraha movement in 1919. In parallel, Gandhi's fellowmen became sceptical of his pacifist ideas and were inspired by the ideas of nationalism and anti-imperialism.[42]

In a 1920 essay, after the World War I, Gandhi wrote, "where there is only a choice between cowardice and violence, I would advise violence." Rahul Sagar interprets Gandhi's efforts to recruit for the British military during the War, as Gandhi's belief that, at that time, it would demonstrate that Indians were willing to fight. Further, it would also show the British that his fellow Indians were "their subjects by choice rather than out of cowardice." In 1922, Gandhi wrote that abstinence from violence is effective and true forgiveness only when one has the power to punish, not when one decides not to do anything because one is helpless.[43]

After World War II engulfed Britain, Gandhi actively campaigned to oppose any help to the British war effort and any Indian participation in the war. According to Arthur Herman, Gandhi believed that his campaign would strike a blow to imperialism.[44] Gandhi's position was not supported by many Indian leaders, and his campaign against the British war effort was a failure. The Hindu leader, Tej Bahadur Sapru, declared in 1941, states Herman, "A good many Congress leaders are fed up with the barren program of the Mahatma".[44] Over 2.5 million Indians ignored Gandhi, volunteered and joined on the British side. They fought and died as a part of the Allied forces in Europe, North Africa and various fronts of the World War II.[44]

Truth and Satyagraha[edit]

Gandhi dedicated his life to discovering and pursuing truth, or Satya, and called his movement satyagraha, which means "appeal to, insistence on, or reliance on the Truth".[45] The first formulation of the satyagraha as a political movement and principle occurred in 1920, which he tabled as "Resolution on Non-cooperation" in September that year before a session of the Indian Congress. It was the satyagraha formulation and step, states Dennis Dalton, that deeply resonated with beliefs and culture of his people, embedded him into the popular consciousness, transforming him quickly into Mahatma.[46]

Gandhi based Satyagraha on the Vedantic ideal of self-realisation, ahimsa (nonviolence), vegetarianism, and universal love. William Borman states that the key to his satyagraha is rooted in the Hindu Upanishadic texts.[47] According to Indira Carr, Gandhi's ideas on ahimsa and satyagraha were founded on the philosophical foundations of Advaita Vedanta.[48] I. Bruce Watson states that some of these ideas are found not only in traditions within Hinduism, but also in Jainism or Buddhism, particularly those about non-violence, vegetarianism and universal love, but Gandhi's synthesis was to politicise these ideas.[49] Gandhi's concept of satya as a civil movement, states Glyn Richards, are best understood in the context of the Hindu terminology of Dharma and Ṛta.[50]

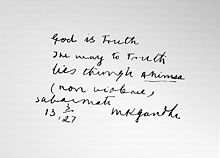

Gandhi stated that the most important battle to fight was overcoming his own demons, fears, and insecurities. Gandhi summarised his beliefs first when he said "God is Truth". He would later change this statement to "Truth is God". Thus, satya (truth) in Gandhi's philosophy is "God".[51] Gandhi, states Richards, described the term "God" not as a separate power, but as the Being (Brahman, Atman) of the Advaita Vedanta tradition, a nondual universal that pervades in all things, in each person and all life.[50] According to Nicholas Gier, this to Gandhi meant the unity of God and humans, that all beings have the same one soul and therefore equality, that atman exists and is same as everything in the universe, ahimsa (non-violence) is the very nature of this atman.[52]

The essence of Satyagraha is "soul force" as a political means, refusing to use brute force against the oppressor, seeking to eliminate antagonisms between the oppressor and the oppressed, aiming to transform or "purify" the oppressor. It is not inaction but determined passive resistance and non-co-operation where, states Arthur Herman, "love conquers hate".[55] A euphemism sometimes used for Satyagraha is that it is a "silent force" or a "soul force" (a term also used by Martin Luther King Jr. during his "I Have a Dream" speech). It arms the individual with moral power rather than physical power. Satyagraha is also termed a "universal force", as it essentially "makes no distinction between kinsmen and strangers, young and old, man and woman, friend and foe."[56]

Gandhi wrote: "There must be no impatience, no barbarity, no insolence, no undue pressure. If we want to cultivate a true spirit of democracy, we cannot afford to be intolerant. Intolerance betrays want of faith in one's cause."[57] Civil disobedience and non-co-operation as practised under Satyagraha are based on the "law of suffering",[58] a doctrine that the endurance of suffering is a means to an end. This end usually implies a moral upliftment or progress of an individual or society. Therefore, non-co-operation in Satyagraha is in fact a means to secure the co-operation of the opponent consistently with truth and justice.[59]

While Gandhi's idea of satyagraha as a political means attracted a widespread following among Indians, the support was not universal. For example, Muslim leaders such as Jinnah opposed the satyagraha idea, accused Gandhi to be reviving Hinduism through political activism, and began effort to counter Gandhi with Muslim nationalism and a demand for Muslim homeland.[60][61][62] The untouchability leader Ambedkar, in June 1945, after his decision to convert to Buddhism and a key architect of the Constitution of modern India, dismissed Gandhi's ideas as loved by "blind Hindu devotees", primitive, influenced by spurious brew of Tolstoy and Ruskin, and "there is always some simpleton to preach them".[63][64] Winston Churchill caricatured Gandhi as a "cunning huckster" seeking selfish gain, an "aspiring dictator", and an "atavistic spokesman of a pagan Hinduism". Churchill stated that the civil disobedience movement spectacle of Gandhi only increased "the danger to which white people there [British India] are exposed".[65]

Nonviolence[edit]

Although Gandhi was not the originator of the principle of nonviolence, he was the first to apply it in the political field on a large scale.[66] The concept of nonviolence (ahimsa) has a long history in Indian religious thought, with it being considered the highest dharma (ethical value virtue), a precept to be observed towards all living beings (sarvbhuta), at all times (sarvada), in all respects (sarvatha), in action, words and thought.[67] Gandhi explains his philosophy and ideas about ahimsa as a political means in his autobiography The Story of My Experiments with Truth.[68][69][70]

Gandhi was criticised for refusing to protest the hanging of Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev, Udham Singh and Rajguru.[71][72] He was accused of accepting a deal with the King's representative Irwin that released civil disobedience leaders from prison and accepted the death sentence against the highly popular revolutionary Bhagat Singh, who at his trial had replied, "Revolution is the inalienable right of mankind".[73] However Congressmen, who were votaries of non-violence, defended Bhagat Singh and other revolutionary nationalists being tried in Lahore.[74]

Gandhi's views came under heavy criticism in Britain when it was under attack from Nazi Germany, and later when the Holocaust was revealed. He told the British people in 1940, "I would like you to lay down the arms you have as being useless for saving you or humanity. You will invite Herr Hitler and Signor Mussolini to take what they want of the countries you call your possessions... If these gentlemen choose to occupy your homes, you will vacate them. If they do not give you free passage out, you will allow yourselves, man, woman, and child, to be slaughtered, but you will refuse to owe allegiance to them."[75] George Orwell remarked that Gandhi's methods confronted "an old-fashioned and rather shaky despotism which treated him in a fairly chivalrous way", not a totalitarian power, "where political opponents simply disappear."[76]

In a post-war interview in 1946, he said, "Hitler killed five million Jews. It is the greatest crime of our time. But the Jews should have offered themselves to the butcher's knife. They should have thrown themselves into the sea from cliffs... It would have aroused the world and the people of Germany... As it is they succumbed anyway in their millions."[77] Gandhi believed this act of "collective suicide", in response to the Holocaust, "would have been heroism".[78]

Gandhi as a politician, in practice, settled for less than complete non-violence. His method of non-violent Satyagraha could easily attract masses and it fitted in with the interests and sentiments of business groups, better-off people and dominant sections of peasantry, who did not want an uncontrolled and violent social revolution which could create losses for them. His doctrine of ahimsa lay at the core of unifying role played by the Gandhian Congress.[79] But during Quit India movement even many staunch Gandhians used 'violent means'.[80]

On inter-religious relations[edit]

Buddhists, Jains and Sikhs[edit]

Gandhi believed that Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism were traditions of Hinduism, with a shared history, rites and ideas. At other times, he acknowledged that he knew little about Buddhism other than his reading of Edwin Arnold's book on it. Based on that book, he considered Buddhism to be a reform movement and the Buddha to be a Hindu.[81] He stated he knew Jainism much more, and he credited Jains to have profoundly influenced him. Sikhism, to Gandhi, was an integral part of Hinduism, in the form of another reform movement. Sikh and Buddhist leaders disagreed with Gandhi, a disagreement Gandhi respected as a difference of opinion.[81][82]

Muslims[edit]

Gandhi had generally positive and empathetic views of Islam, and he extensively studied the Quran. He viewed Islam as a faith that proactively promoted peace, and felt that non-violence had a predominant place in the Quran.[83] He also read the Islamic prophet Muhammad's biography, and argued that it was "not the sword that won a place for Islam in those days in the scheme of life. It was the rigid simplicity, the utter self-effacement of the Prophet, the scrupulous regard for pledges, his intense devotion to his friends and followers, his intrepidity, his fearlessness, his absolute trust in God and in his own mission."[84] Gandhi had a large Indian Muslim following, who he encouraged to join him in a mutual nonviolent jihad against the social oppression of their time. Prominent Muslim allies in his nonviolent resistance movement included Maulana Abul Kalam Azad and Abdul Ghaffar Khan. However, Gandhi's empathy towards Islam, and his eager willingness to valorise peaceful Muslim social activists, was viewed by many Hindus as an appeasement of Muslims and later became a leading cause for his assassination at the hands of intolerant Hindu extremists.[85]

While Gandhi expressed mostly positive views of Islam, he did occasionally criticise Muslims.[83] He stated in 1925 that he did not criticise the teachings of the Quran, but he did criticise the interpreters of the Quran. Gandhi believed that numerous interpreters have interpreted it to fit their preconceived notions.[86] He believed Muslims should welcome criticism of the Quran, because "every true scripture only gains from criticism". Gandhi criticised Muslims who "betray intolerance of criticism by a non-Muslim of anything related to Islam", such as the penalty of stoning to death under Islamic law. To Gandhi, Islam has "nothing to fear from criticism even if it be unreasonable".[87][88] He also believed there were material contradictions between Hinduism and Islam,[88] and he criticised Muslims along with communists that were quick to resort to violence.[89]

One of the strategies Gandhi adopted was to work with Muslim leaders of pre-partition India, to oppose the British imperialism in and outside the Indian subcontinent.[90][91] After the World War I, in 1919–22, he won Muslim leadership support of Ali Brothers by backing the Khilafat Movement in favour the Islamic Caliph and his historic Ottoman Caliphate, and opposing the secular Islam supporting Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. By 1924, Atatürk had ended the Caliphate, the Khilafat Movement was over, and Muslim support for Gandhi had largely evaporated.[90][92][91]

In 1925, Gandhi gave another reason to why he got involved in the Khilafat movement and the Middle East affairs between Britain and the Ottoman Empire. Gandhi explained to his co-religionists (Hindu) that he sympathised and campaigned for the Islamic cause, not because he cared for the Sultan, but because "I wanted to enlist the Mussalman's sympathy in the matter of cow protection".[93] According to the historian M. Naeem Qureshi, like the then Indian Muslim leaders who had combined religion and politics, Gandhi too imported his religion into his political strategy during the Khilafat movement.[94]

In the 1940s, Gandhi pooled ideas with some Muslim leaders who sought religious harmony like him, and opposed the proposed partition of British India into India and Pakistan. For example, his close friend Badshah Khan suggested that they should work towards opening Hindu temples for Muslim prayers, and Islamic mosques for Hindu prayers, to bring the two religious groups closer.[95] Gandhi accepted this and began having Muslim prayers read in Hindu temples to play his part, but was unable to get Hindu prayers read in mosques. The Hindu nationalist groups objected and began confronting Gandhi for this one-sided practice, by shouting and demonstrating inside the Hindu temples, in the last years of his life.[96][97][98]

Christians[edit]

Gandhi criticised as well as praised Christianity. He was critical of Christian missionary efforts in British India, because they mixed medical or education assistance with demands that the beneficiary convert to Christianity.[99] According to Gandhi, this was not true "service" but one driven by an ulterior motive of luring people into religious conversion and exploiting the economically or medically desperate. It did not lead to inner transformation or moral advance or to the Christian teaching of "love", but was based on false one-sided criticisms of other religions, when Christian societies faced similar problems in South Africa and Europe. It led to the converted person hating his neighbours and other religions, and divided people rather than bringing them closer in compassion. According to Gandhi, "no religious tradition could claim a monopoly over truth or salvation".[99][100] Gandhi did not support laws to prohibit missionary activity, but demanded that Christians should first understand the message of Jesus, and then strive to live without stereotyping and misrepresenting other religions. According to Gandhi, the message of Jesus was not to humiliate and imperialistically rule over other people considering them inferior or second class or slaves, but that "when the hungry are fed and peace comes to our individual and collective life, then Christ is born".[101]

Gandhi believed that his long acquaintance with Christianity had made him like it as well as find it imperfect. He asked Christians to stop humiliating his country and his people as heathens, idolators and other abusive language, and to change their negative views of India. He believed that Christians should introspect on the "true meaning of religion" and get a desire to study and learn from Indian religions in the spirit of universal brotherhood.[101] According to Eric Sharpe – a professor of Religious Studies, though Gandhi was born in a Hindu family and later became Hindu by conviction, many Christians in time thought of him as an "exemplary Christian and even as a saint".[102]

Some colonial era Christian preachers and faithfuls considered Gandhi as a saint.[103][104][105] Biographers from France and Britain have drawn parallels between Gandhi and Christian saints. Recent scholars question these romantic biographies and state that Gandhi was neither a Christian figure nor mirrored a Christian saint.[106] Gandhi's life is better viewed as exemplifying his belief in the "convergence of various spiritualities" of a Christian and a Hindu, states Michael de Saint-Cheron.[106]

Jews[edit]

According to Kumaraswamy, Gandhi initially supported Arab demands with respect to Palestine. He justified this support by invoking Islam, stating that "non-Muslims cannot acquire sovereign jurisdiction" in Jazirat al-Arab (the Arabian Peninsula).[107] These arguments, states Kumaraswamy, were a part of his political strategy to win Muslim support during the Khilafat movement. In the post-Khilafat period, Gandhi neither negated Jewish demands nor did he use Islamic texts or history to support Muslim claims against Israel. Gandhi's silence after the Khilafat period may represent an evolution in his understanding of the conflicting religious claims over Palestine, according to Kumaraswamy.[107] In 1938, Gandhi spoke in favour of Jewish claims, and in March 1946, he said to the Member of British Parliament Sidney Silverman, "if the Arabs have a claim to Palestine, the Jews have a prior claim", a position very different from his earlier stance.[107][108]

Gandhi discussed the persecution of the Jews in Germany and the emigration of Jews from Europe to Palestine through his lens of Satyagraha.[109][110] In 1937, Gandhi discussed Zionism with his close Jewish friend Hermann Kallenbach.[111] He said that Zionism was not the right answer to the problems faced by Jews[112] and instead recommended Satyagraha. Gandhi thought the Zionists in Palestine represented European imperialism and used violence to achieve their goals; he argued that "the Jews should disclaim any intention of realising their aspiration under the protection of arms and should rely wholly on the goodwill of Arabs. No exception can possibly be taken to the natural desire of the Jews to find a home in Palestine. But they must wait for its fulfilment till Arab opinion is ripe for it."[109]

In 1938, Gandhi stated that his "sympathies are all with the Jews. I have known them intimately in South Africa. Some of them became life-long companions." Philosopher Martin Buber was highly critical of Gandhi's approach and in 1939 wrote an open letter to him on the subject. Gandhi reiterated his stance that "the Jews seek to convert the Arab heart", and use "satyagraha in confronting the Arabs" in 1947.[113] According to Simone Panter-Brick, Gandhi's political position on Jewish-Arab conflict evolved over the 1917–1947 period, shifting from a support for the Arab position first, and for the Jewish position in the 1940s.[114]

References[edit]

- ^ William Borman (1986). Gandhi and Non-Violence. State University of New York Press. pp. 192–95, 208–29. ISBN 978-0-88706-331-2.

- ^ Dennis Dalton (2012). Mahatma Gandhi: Nonviolent Power in Action. Columbia University Press. pp. 30–35. ISBN 978-0-231-15959-3., Quote: "Yet he [Gandhi] must bear some of the responsibility for losing his followers along the way. The sheer vagueness and contradictions recurrent throughout his writing made it easier to accept him as a saint than to fathom the challenge posed by his demanding beliefs. Gandhi saw no harm in self-contradictions: life was a series of experiments, and any principle might change if Truth so dictated".

- ^ a b Brown, Judith M. & Parel, Anthony (2011). The Cambridge Companion to Gandhi. Cambridge University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-521-13345-6.

- ^ Indira Carr (2012). Stuart Brown; et al. (eds.). Biographical Dictionary of Twentieth-Century Philosophers. Routledge. pp. 263–64. ISBN 978-1-134-92796-8., Quote: "Gandhi, Mohandas Karamchand. Indian. born: 2 October 1869, Gujarat; (...) Influences: Vaishnavism, Jainism and Advaita Vedanta."

- ^ J. Jordens (1998). Gandhi's Religion: A Homespun Shawl. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-230-37389-1.

I am an advaitist, and yet I can support Dvaitism

- ^ Jeffrey D. Long (2008). Rita Sherma and Arvind Sharma (ed.). Hermeneutics and Hindu Thought: Toward a Fusion of Horizons. Springer. p. 194. ISBN 978-1-4020-8192-7.

- ^ Gandhi, Mahatma (2013). Hinduism According to Gandhi: Thoughts, Writings and Critical Interpretation. Orient Paperbacks. p. 85. ISBN 978-81-222-0558-9.

- ^ Anil Mishra (2012). Reading Gandhi. Pearson. p. 2. ISBN 978-81-317-9964-2.

- ^ Cribb, R. B. (1985). "The Early Political Philosophy of M. K. Gandhi, 1869–1893". Asian Profile. 13 (4): 353–60.

- ^ Crib (1985).

- ^ Parekh, Bhikhu C. (2001). Gandhi: a very short introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-19-285457-5.

- ^ Bhikhu C. Parekh (2001). Gandhi. Sterling Publishing. pp. 43, 71. ISBN 978-1-4027-6887-3.

- ^ Indira Carr (2012). Stuart Brown; et al. (eds.). Biographical Dictionary of Twentieth-Century Philosophers. Routledge. p. 263. ISBN 978-1-134-92796-8.

- ^ Glyn Richards (2016). Studies in Religion: A Comparative Approach to Theological and Philosophical Themes. Springer. pp. 64–78. ISBN 978-1-349-24147-7.

- ^ Gokhale, Balkrishna Govind (1972). "Gandhi and History". History and Theory. 11 (2): 214–25. doi:10.2307/2504587. JSTOR 2504587.

- ^ Williams, Raymond Brady (2001). An introduction to Swaminarayan Hinduism. Cambridge University Press. p. 173. ISBN 0-521-65422-X.

- ^ Meller, Helen Elizabeth (1994). Patrick Geddes: social evolutionist and city planner. Routledge. p. 159. ISBN 0-415-10393-2.

- ^ Spodek, Howard (1971). "On the Origins of Gandhi's Political Methodology: The Heritage of Kathiawad and Gujarat". Journal of Asian Studies. 30 (2): 361–72. doi:10.2307/2942919. JSTOR 2942919.

- ^ B. Srinivasa Murthy, ed. (1987). Mahatma Gandhi and Leo Tolstoy: Letters. ISBN 0-941910-03-2.

- ^ Murthy, B. Srinivasa, ed. (1987). Mahatma Gandhi and Leo Tolstoy: Letters (PDF). Long Beach, California: Long Beach Publications. ISBN 0-941910-03-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 September 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ^ Green, Martin Burgess (1986). The origins of nonviolence: Tolstoy and Gandhi in their historical settings. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-00414-3. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ^ Bhana, Surendra (1979). "Tolstoy Farm, A Satyagrahi's Battle Ground". Journal of Indian History. 57 (2/3): 431–40.

- ^ "Raychandbhai". MK Gandhi. Bombay Sarvodaya Mandal & Gandhi Research Foundation. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ Gandhi, Mahatma (1993). Gandhi: An Autobiography (Beacon Press ed.). pp. 63–65. ISBN 0-8070-5909-9.

- ^ Webber, Thomas (2011). Gandhi as Disciple and Mentor (3 ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 33–36. ISBN 978-0-521-17448-0.

- ^ Gandhi, Mahatma (June 1930). "Modern Review".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Gandhi1957was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Thomas Weber (2004). Gandhi as Disciple and Mentor. Cambridge University Press. pp. 34–36. ISBN 978-1-139-45657-9.

- ^ a b c d "Mahatma Gandhi – The religious quest | Biography, Accomplishments, & Facts". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2015. Archived from the original on 13 May 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ^ Martin Burgess Green (1993). Gandhi: voice of a new age revolution. Continuum. pp. 123–25. ISBN 978-0-8264-0620-0.

- ^ Fischer Louis (1950). The life of Mahatma Gandhi. HarperCollins. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-06-091038-9.

- ^ Ghose, Sankar (1991). Mahatma Gandhi. Allied Publishers. pp. 377–78. ISBN 978-81-7023-205-6.

- ^ Richard H. Davis (2014). The "Bhagavad Gita": A Biography. Princeton University Press. pp. 137–45. ISBN 978-1-4008-5197-3.

- ^ Suhrud, Tridip (November–December 2018). "The Story of Antaryami". Social Scientist. 46 (11–12): 45. JSTOR 26599997.

- ^ Chatterjee, Margaret (2005). Gandhi and the Challenge of Religious Diversity: Religious Pluralism Revisited. Bibliophile South Asia. p. 119. ISBN 978-81-85002-46-0.

- ^ Fiala, Andrew (2018). The Routledge Handbook of Pacifism and Nonviolence. Routledge. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-317-27197-0., Fiala quotes Ambitabh Pal, "Gandhi himself followed a strand of Hinduism that with its emphasis on service and on poetry and songs bore similarities to Sufi Islam".

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Hermanwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d Ghose, Sankar (1991). Mahatma Gandhi. Allied Publishers. p. 275. ISBN 978-81-7023-205-6.

- ^ "Returning his Medals". Bombay Sarvodaya Mandal & Gandhi Research Foundation. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

When the war was declared, my personal sympathies were all with the Boers, but my loyalty to the British rule drove me to participation with the British in that war. I felt that, if I demanded rights as a British citizen, it was also my duty, as such to participate in the defence of the British Empire. so I collected together as many comrades as possible, and with very great difficulty got their services accepted as an ambulance corps.

- ^ a b Michael J. Green; Nicholas Szechenyi (2017). A Global History of the Twentieth Century: Legacies and Lessons from Six National Perspectives. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-1-4422-7972-8.

- ^ Keith Robbins (2002). The First World War. Oxford University Press. pp. 133–37. ISBN 978-0-19-280318-4.

- ^ Rahul Sagar (2015). David M. Malone; et al. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Indian Foreign Policy. Oxford University Press. pp. 71–73. ISBN 978-0-19-106118-9.

- ^ Rahul Sagar (2015). David M. Malone; et al. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Indian Foreign Policy. Oxford University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-19-106118-9.

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

herman467was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Gene Sharp (1960). Gandhi Wields the Weapon of Moral Power: Three Case Histories. Navajivan. p. 4.

- ^ Dennis Dalton (2012). Mahatma Gandhi: Nonviolent Power in Action. Columbia University Press. pp. 30–32. ISBN 978-0-231-15959-3.

- ^ William Borman (1986). Gandhi and Non-Violence. State University of New York Press. pp. 26–34. ISBN 978-0-88706-331-2.

- ^ Indira Carr (2012). Stuart Brown; et al. (eds.). Biographical Dictionary of Twentieth-Century Philosophers. Routledge. p. 264. ISBN 978-1-134-92796-8.

- ^ Watson, I. Bruce (1977). "Satyagraha: The Gandhian Synthesis". Journal of Indian History. 55 (1/2): 325–35.

- ^ a b Glyn Richards (1986), "Gandhi's Concept of Truth and the Advaita Tradition", Religious Studies, Cambridge University Press, Vol. 22, No. 1 (Mar. 1986), pp. 1–14

- ^ Parel, Anthony (2006). Gandhi's Philosophy and the Quest for Harmony. Cambridge University Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-521-86715-3. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ^ Nicholas F. Gier (2004). The Virtue of Nonviolence: From Gautama to Gandhi. State University of New York Press. pp. 40–42. ISBN 978-0-7914-5949-2.

- ^ Salt March: Indian History Archived 1 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Sita Anantha Raman (2009). Women in India: A Social and Cultural History. ABC-CLIO. pp. 164–66. ISBN 978-0-313-01440-6.

- ^ Arthur Herman (2008). Gandhi & Churchill: The Epic Rivalry that Destroyed an Empire and Forged Our Age. Random House. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-553-90504-5.

- ^ Gandhi, M.K. "Some Rules of Satyagraha Young India (Navajivan) 23 February 1930". The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi. 48: 340.

- ^ Prabhu, R. K. and Rao, U. R. (eds.) (1967) from section "Power of Satyagraha" Archived 2 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, of the book The Mind of Mahatma Gandhi, Ahemadabad, India.

- ^ Gandhi, M. K. (1982) [Young India, 16 June 1920]. "156. The Law of Suffering" (PDF). Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi. Vol. 20 (electronic ed.). New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Govt. of India. pp. 396–99. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 January 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ^ Sharma, Jai Narain (2008). Satyagraha: Gandhi's approach to conflict resolution. Concept Publishing Company. p. 17. ISBN 978-81-8069-480-6. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ^ R. Taras (2002). Liberal and Illiberal Nationalisms. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-230-59640-5., Quote: "In 1920 Jinnah opposed satyagraha and resigned from the Congress, boosting the fortunes of the Muslim League."

- ^ Yasmin Khan (2007). The Great Partition: The Making of India and Pakistan. Yale University Press. pp. 11–22. ISBN 978-0-300-12078-3.

- ^ Rafiq Zakaria (2002). The Man who Divided India. Popular Prakashan. pp. 83–85. ISBN 978-81-7991-145-7.

- ^ Arthur Herman (2008). Gandhi & Churchill: The Epic Rivalry that Destroyed an Empire and Forged Our Age. Random House. p. 586. ISBN 978-0-553-90504-5. Archived from the original on 13 September 2014.

- ^ Cháirez-Garza, Jesús Francisco (2 January 2014). "Touching space: Ambedkar on the spatial features of untouchability". Contemporary South Asia. 22 (1). Taylor & Francis: 37–50. doi:10.1080/09584935.2013.870978. S2CID 145020542.;

B.R. Ambedkar (1945), What Congress and Gandhi have done to the Untouchables, Thacker & Co. Editions, First Edition, pp. v, 282–97 - ^ Arthur Herman (2008). Gandhi & Churchill: The Epic Rivalry that Destroyed an Empire and Forged Our Age. Random House. pp. 359, 378–80. ISBN 978-0-553-90504-5. Archived from the original on 13 September 2014.

- ^ Asirvatham, Eddy (1995). Political Theory. S.chand. ISBN 81-219-0346-7.

- ^ Christopher Chapple (1993). Nonviolence to Animals, Earth, and Self in Asian Traditions. State University of New York Press. pp. 16–18, 54–57. ISBN 978-0-7914-1497-2.

- ^ Gandhi, Mohandis K. (11 August 1920), "The Doctrine of the Sword", Young India, M. K. Gandhi: 3, retrieved 3 May 2017 Cited from Borman, William (1986). Gandhi and nonviolence. SUNY Press. p. 253. ISBN 978-0-88706-331-2.

- ^ Faisal Devji, The Impossible Indian: Gandhi and the Temptation of Violence (Harvard University Press; 2012)

- ^ Johnson, Richard L. (2006). Gandhi's Experiments With Truth: Essential Writings By And About Mahatma Gandhi. Lexington Books. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-7391-1143-7. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- ^ Mahatma Gandhi on Bhagat Singh.

- ^ Rai, Raghunath (1992). Themes in Indian History. FK Publications. p. 282. ISBN 978-81-89611-62-0.

- ^ Sankar Ghose (1991). Mahatma Gandhi. Allied Publishers. pp. 199–204. ISBN 978-81-7023-205-6.

- ^ Chandra, Bipin (1999). India since independence. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-143-10409-4.

- ^ Wolpert, p. 197.

- ^ Orwell, review of Louis Fischer's Gandhi and Stalin, The Observer, 10 October 1948, reprinted in It Is what I Think, pp. 452–53.

- ^ Fischer, Louis (1950). The life of Mahatma Gandhi. Harper. p. 348. ISBN 978-0-06-091038-9.

- ^ George Orwell, "Reflections on Gandhi", Partisan Review, January 1949.

- ^ Reddy, K Krishna (2011). Indian History. New Delhi: McGraw Hill Education. pp. C214. ISBN 978-0-07-132923-1.

- ^ Chandra, Bipan (1988). India's Struggle for Independence (PDF). Penguin Books. p. 475. ISBN 978-8-184-75183-3.

- ^ a b J.T.F. Jordens (1998). Gandhi's Religion: A Homespun Shawl. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 107–08. ISBN 978-0-230-37389-1.

- ^ Nikky-Guninder Kaur Singh (2003). Harold Coward (ed.). Indian Critiques of Gandhi. State University of New York Press. pp. 185–88. ISBN 978-0-7914-8588-0.

- ^ a b Gorder, A. Christian Van (2014). Islam, Peace and Social Justice: A Christian Perspective. James Clarke & Co. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-227-90200-4.

- ^ Malekian, Farhad (2018). Corpus Juris of Islamic International Criminal Justice. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 409. ISBN 978-1-5275-1693-9.

- ^ Yasmin Khan, "Performing Peace: Gandhi's assassination as a critical moment in the consolidation of the Nehruvian state." Modern Asian Studies 45.1 (2011): 57–80.

- ^ M K Gandhi (1925). Young India. Navajivan Publishing. pp. 81–82.

- ^ Mohandas Karmchand Gandhi (2004). V Geetha (ed.). Soul Force: Gandhi's Writings on Peace. Gandhi Publications Trust. pp. 193–94. ISBN 978-81-86211-85-4.

- ^ a b Mohandas K. Gandhi; Michael Nagler (Ed) (2006). Gandhi on Islam. Berkeley Hills. pp. 1–17, 31–38. ISBN 1-893163-64-4.

- ^ Niranjan Ramakrishnan (2013). Reading Gandhi in the Twenty-First Century. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-137-32514-3.

- ^ a b Sarah C.M. Paine (2015). Nation Building, State Building, and Economic Development: Case Studies and Comparisons. Routledge. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-1-317-46409-9.

- ^ a b Ghose, Sankar (1991). Mahatma Gandhi. Allied Publishers. pp. 161–64. ISBN 978-81-7023-205-6.

- ^ Kumaraswamy, P. R. (1992). "Mahatma Gandhi and the Jewish National Home: An Assessment". Asian and African Studies: Journal of the Israel Oriental Society. 26 (1): 1–13.

- ^ Simone Panter-Brick (2015). Gandhi and Nationalism: The Path to Indian Independence. I.B. Tauris. pp. 118–19. ISBN 978-1-78453-023-5.

- ^ M. Naeem Qureshi (1999). Reinhard Schulze (ed.). Pan-Islam in British Indian Politics: A Study of the Khilafat Movement, 1918–1924. Brill Academic. pp. 104–05 with footnotes. ISBN 90-04-11371-1. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016.

- ^ Muhammad Soaleh Korejo (1993). The Frontier Gandhi: His Place in History. Oxford University Press. pp. 77–79. ISBN 978-0-19-577461-0.

- ^ Stanley Wolpert (2001). Gandhi's Passion: The Life and Legacy of Mahatma Gandhi. Oxford University Press. pp. 243–44. ISBN 978-0-19-972872-5.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

godse1948was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Rein Fernhout (1995). ʻAbd Allāh Aḥmad Naʻim, Jerald Gort and Henry Jansen (ed.). Human Rights and Religious Values: An Uneasy Relationship?. Rodopi. pp. 126–31. ISBN 978-90-5183-777-3.

- ^ a b Chad M. Bauman (2015). Pentecostals, Proselytization, and Anti-Christian Violence in Contemporary India. Oxford University Press. pp. 50, 56–59, 66. ISBN 978-0-19-020210-1.

- ^ Robert Eric Frykenberg; Richard Fox Young (2009). India and the Indianness of Christianity. Wm. B. Eerdmans. pp. 211–14. ISBN 978-0-8028-6392-8.

- ^ a b John C.B. Webster (1993). Harold Coward (ed.). Hindu-Christian Dialogue: Perspectives and Encounters. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 81–86, 89–95. ISBN 978-81-208-1158-4. Archived from the original on 17 March 2015.

- ^ Eric J. Sharpe (1993). Harold Coward (ed.). Hindu-Christian Dialogue: Perspectives and Encounters. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 105. ISBN 978-81-208-1158-4. Archived from the original on 17 March 2015.

- ^ Johnson, R.L. (2006). Gandhi's Experiments with Truth: Essential Writings by and about Mahatma Gandhi. Studies in Comparative Philosophy. Lexington Books. p. 269. ISBN 978-0-7391-1143-7.

- ^ Markovits, C. (2004). The UnGandhian Gandhi: The Life and Afterlife of the Mahatma. Anthem South Asian studies. Anthem Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-84331-127-0.

- ^ Rudolph, L.I.; Rudolph, S.H. (2010). Postmodern Gandhi and Other Essays: Gandhi in the World and at Home. University of Chicago Press. pp. 99, 114–18. ISBN 978-0-226-73131-5.

- ^ a b de Saint-Cheron, M. (2017). Gandhi: Anti-Biography of a Great Soul. Taylor & Francis. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-351-47062-9. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ a b c P. R. Kumaraswamy (2010). India's Israel Policy. Columbia University Press. pp. 36–38. ISBN 978-0-231-52548-0.

- ^ Fischer Louis (1950). The life of Mahatma Gandhi. HarperCollins. p. 424. ISBN 978-0-06-091038-9.

- ^ a b Lelyveld, Joseph (2011). Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle with India. Random House Digital, Inc. pp. 278–81. ISBN 978-0-307-26958-4.

- ^ Panter-Brick, Simone (2008), Gandhi and the Middle East: Jews, Arabs and Imperial Interests. London: I.B. Tauris, ISBN 1-84511-584-8.

- ^ Panter-Brick, Simone. "Gandhi's Dream of Hindu-Muslim Unity and its two Offshoots in the Middle East" Archived 17 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Durham Anthropology Journal, Volume 16(2), 2009: pp. 54–66.

- ^ Jack, p. 317.

- ^ Murti, Ramana V.V. (1968). "Buber's Dialogue and Gandhi's Satyagraha". Journal of the History of Ideas. 29 (4): 605–13. doi:10.2307/2708297. JSTOR 2708297.

- ^ Simone Panter-Brick (2009), "Gandhi's Views on the Resolution of the Conflict in Palestine: A Note", Middle Eastern Studies, Taylor & Francis, Vol. 45, No. 1 (Jan. 2009), pp. 127–33

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "BhanaVahed2005" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "Brown1974" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "Coward2003" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "GWPM" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "GreatSoulReview" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "Guardian-2008-ashes" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "Hardiman2001" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "ie48pg5" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "ie48" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "Khan2011" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "Kumar2006" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "Lapping1989" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "Mbeki2006" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "Mohanty2011" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "Murali1985" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "Norvell1997" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "Sarkar2006" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "Sarma1994" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "Sorokin2002" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "Tendulkar1951" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "Whiggism" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Bibliography[edit]

Books[edit]

- Ahmed, Talat (2018). Mohandas Gandhi: Experiments in Civil Disobedience ISBN 0-7453-3429-6

- Barr, F. Mary (1956). Bapu: Conversations and Correspondence with Mahatma Gandhi (2nd ed.). Bombay: International Book House. OCLC 8372568. (see book article)

- Bondurant, Joan Valérie (1971). Conquest of Violence: the Gandhian philosophy of conflict. University of California Press.

- Brown, Judith M. (2004). "Gandhi, Mohandas Karamchand [Mahatma Gandhi] (1869–1948)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press.[ISBN missing]

- Brown, Judith M., and Anthony Parel, eds. The Cambridge Companion to Gandhi (2012); 14 essays by scholars

- Brown, Judith Margaret (1991). Gandhi: Prisoner of Hope. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05125-4.

- Chadha, Yogesh (1997). Gandhi: a life. John Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-24378-6.

- Dwivedi, Divya; Mohan, Shaj; Nancy, Jean-Luc (2019). Gandhi and Philosophy: On Theological Anti-politics. Bloomsbury Academic, UK. ISBN 978-1-4742-2173-3.

- Louis Fischer. The Life of Mahatma Gandhi (1957) online

- Easwaran, Eknath (2011). Gandhi the Man: How One Man Changed Himself to Change the World. Nilgiri Press. ISBN 978-1-58638-055-7.

- Hook, Sue Vander (2010). Mahatma Gandhi: Proponent of Peace. ABDO. ISBN 978-1-61758-813-6.

- Gandhi, Rajmohan (1990), Patel, A Life, Navajivan Pub. House

- Gandhi, Rajmohan (2006). Gandhi: The Man, His People, and the Empire. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25570-8.

- Gangrade, K.D. (2004). "Role of Shanti Sainiks in the Global Race for Armaments". Moral Lessons From Gandhi's Autobiography And Other Essays. Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 978-81-8069-084-6.

- Guha, Ramachandra (2013). Gandhi Before India. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-385-53230-3.

- Hardiman, David (2003). Gandhi in His Time and Ours: the global legacy of his ideas. C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 978-1-85065-711-8.

- Hatt, Christine (2002). Mahatma Gandhi. Evans Brothers. ISBN 978-0-237-52308-4.

- Herman, Arthur (2008). Gandhi and Churchill: the epic rivalry that destroyed an empire and forged our age. Random House Digital, Inc. ISBN 978-0-553-80463-8.

- Jai, Janak Raj (1996). Commissions and Omissions by Indian Prime Ministers: 1947–1980. Regency Publications. ISBN 978-81-86030-23-3.

- Johnson, Richard L. (2006). Gandhi's Experiments with Truth: Essential Writings by and about Mahatma Gandhi. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-1143-7.

- Jones, Constance & Ryan, James D. (2007). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase Publishing. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-8160-5458-9.

- Majmudar, Uma (2005). Gandhi's Pilgrimage of Faith: from darkness to light. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-6405-2.

- Miller, Jake C. (2002). Prophets of a just society. Nova Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59033-068-5.

- Pāṇḍeya, Viśva Mohana (2003). Historiography of India's Partition: an analysis of imperialist writings. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 978-81-269-0314-6.

- Pilisuk, Marc; Nagler, Michael N. (2011). Peace Movements Worldwide: Players and practices in resistance to war. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-36482-2.

- Rühe, Peter (2004). Gandhi. Phaidon. ISBN 978-0-7148-4459-6.

- Schouten, Jan Peter (2008). Jesus as Guru: the image of Christ among Hindus and Christians in India. Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-2443-4.

- Sharp, Gene (1979). Gandhi as a Political Strategist: with essays on ethics and politics. P. Sargent Publishers. ISBN 978-0-87558-090-6.

- Shashi, S. S. (1996). Encyclopaedia Indica: India, Pakistan, Bangladesh. Anmol Publications. ISBN 978-81-7041-859-7.

- Sinha, Satya (2015). The Dialectic of God: The Theosophical Views Of Tagore and Gandhi. Partridge Publishing India. ISBN 978-1-4828-4748-2.

- Sofri, Gianni (1999). Gandhi and India: a century in focus. Windrush Press. ISBN 978-1-900624-12-1.

- Thacker, Dhirubhai (2006). ""Gandhi, Mohandas Karamchand" (entry)". In Amaresh Datta (ed.). The Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature (Volume Two) (Devraj To Jyoti). Sahitya Akademi. p. 1345. ISBN 978-81-260-1194-0.

- Todd, Anne M (2004). Mohandas Gandhi. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7910-7864-8.; short biography for children

- Wolpert, Stanley (2002). Gandhi's Passion: the life and legacy of Mahatma Gandhi. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-972872-5.

Scholarly articles[edit]

- Danielson, Leilah C. "'In My Extremity I Turned to Gandhi': American Pacifists, Christianity, and Gandhian Nonviolence, 1915–1941." Church History 72.2 (2003): 361–388.

- Du Toit, Brian M. "The Mahatma Gandhi and South Africa." Journal of Modern African Studies 34#4 (1996): 643–660. online.

- Gokhale, B. G. "Gandhi and the British Empire," History Today (Nov 1969), 19#11 pp 744–751 online.

- Juergensmeyer, Mark. "The Gandhi Revival – A Review Article." The Journal of Asian Studies 43#2 (Feb., 1984), pp. 293–298 online

- Kishwar, Madhu. "Gandhi on Women." Economic and Political Weekly 20, no. 41 (1985): 1753–758. online.

- Murthy, C. S. H. N., Oinam Bedajit Meitei, and Dapkupar Tariang. "The Tale Of Gandhi Through The Lens: An Inter-Textual Analytical Study Of Three Major Films-Gandhi, The Making Of The Mahatma, And Gandhi, My Father." CINEJ Cinema Journal 2.2 (2013): 4–37. online

- Power, Paul F. "Toward a Revaluation of Gandhi's Political Thought." Western Political Quarterly 16.1 (1963): 99–108 excerpt.

- Rudolph, Lloyd I. "Gandhi in the Mind of America." Economic and Political Weekly 45, no. 47 (2010): 23–26. online.

Primary sources[edit]

- Abel M (2005). Glimpses of Indian National Movement. ICFAI Books. ISBN 978-81-7881-420-9.

- Andrews, C. F. (2008) [1930]. "VII – The Teaching of Ahimsa". Mahatma Gandhi's Ideas Including Selections from His Writings. Pierides Press. ISBN 978-1-4437-3309-0.

- Dalton, Dennis, ed. (1996). Mahatma Gandhi: Selected Political Writings. Hackett Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87220-330-3.

- Duncan, Ronald, ed. (2011). Selected Writings of Mahatma Gandhi. Literary Licensing, LLC. ISBN 978-1-258-00907-6.

- Gandhi, M. K.; Fischer, Louis (2002). Louis Fischer (ed.). The Essential Gandhi: An Anthology of His Writings on His Life, Work and Ideas. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-1-4000-3050-7.

- Gandhi, Mohandas Karamchand (1928). Satyagraha in South Africa (in Gujarati) (1 ed.). Ahmedabad: Navajivan Publishing House.

Translated by Valji G. Desai

- Gandhi, Mohandas Karamchand (1994). The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi. Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Govt. of India. ISBN 978-81-230-0239-2. (100 volumes). Free online access from Gandhiserve.

- Gandhi, Mohandas Karamchand (1928). "Drain Inspector's Report". The United States of India. 5 (6–8): 3–4.

- Gandhi, Mohandas Karamchand (1990), Desai, Mahadev H. (ed.), Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments With Truth, Mineola, N.Y.: Dover, ISBN 0-486-24593-4

- Gandhi, Rajmohan (2007). Mohandas: True Story of a Man, His People. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 978-81-8475-317-2.

- Guha, Ramachandra (2013). Gandhi Before India. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 978-93-5118-322-8.

- Jack, Homer A., ed. (1994). The Gandhi Reader: A Source Book of His Life and Writings. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-3161-4.

- Johnson, Richard L. & Gandhi, M. K. (2006). Gandhi's Experiments With Truth: Essential Writings by and about Mahatma Gandhi. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-1143-7.

- Todd, Anne M. (2009). Mohandas Gandhi. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-0662-5.

- Parel, Anthony J., ed. (2009). Gandhi: "Hind Swaraj" and Other Writings Centenary Edition. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-14602-9.