User:Mychm52/sandbox

Bonnet-Dechaume-Blanc syndrome, also known as Wyburn-Mason Syndrome, is a rare congential arteriovenous malformation of the brain, retina or facial nevi.[1] The syndrome has a number of possible symptoms and can affect the skin, bones, kidneys, muscles, and gastrointestinal tract.[2] When the syndrome affects the brain, people can experience severe headaches, seizures, acute stroke, meningism and progressive neurological deficits due to acute or chronic ischaemia caused by arteriovenous shunting.[2][3]

As for the retina, the syndrome causes retinocephalic vascular malformations that tend to be present with intracranial hemorrhage and lead to decreased visual acuity, proptosis, pupillary defects, optic atrophy, congestion of bulbar conjunctiva, and visual field defects.[4][5] Retinal lesions can be unilateral and tortuous, and symptoms begin to appear in the second and third decades of life.[3][5]

The syndrome can present cutaneous (pertaining to the skin) lesions, or skin with different texture, thickness, and color, usually on the face.[4] The facial features caused by the syndrome vary from slight discoloration to extensive nevi and angiomas of the skin.[5] In some cases, the frontal and maxillary sinus can present problems in the subject due to the syndrome.[4]

There have only been 52 reported cases of patients with Bonnet-Dechaume-Blanc syndrome as of 2012.[2] Bonnet-Dechaume-Blanc syndrome is caused by a congenital disorder that is developed by disruption of developing tissues that lead to abnormalities in vascular tissues of the eye.[4] Symptoms are rarely noticed in children and the syndrome is often diagnosed in late childhood or early adulthood when visual impairment is noticed.[3] Fluorescein angiography is commonly used to diagnose the syndrome.[6]

There have been controversies on treatment for patients who display Bonnet-Dechaume Blanc syndrome. Patients with intracranial lesions have been treated with surgical intervention and in some cases, this procedure has been successful. Other treatments include embolization, radiation therapy, and continued observation.[4]

Since the syndrome is rare and non-heritable, research has been focused on the clinical and radiological findings rather than how to manage the syndrome.[3]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

Typically not diagnosed until late childhood or later, Bonnet-Dechaume-Blanc Syndrome usually presents itself with a combination of central nervous system features (midbrain), ophthalmic features (retina), and facial features.[7] The degree of expression of the syndrome's components varies both clinically and structurally. Common symptoms that lead to diagnosis are headaches, retro-orbital pain and hemianopia.[4]

The ophthalmic features of the Bonnet-Dechaume-Blanc Syndrome occur as retinal arteriovenous malformations (AVMs). There are three categories of AVMs that are categorized depending on the severity of the malformation. The first category consists of the patient having small lesions that usually do not produce any symptoms (asymptomatic). The second category, more severe than the first, is when the patient’s malformation is missing a connecting capillary. The missing capillary is meant to serve as a link between an artery and a vein; without it, edemas, hemorrhages and visual impairments can result. Category three, the most severe, occurs when the patient’s malformations are so severe that the dilated vessels cause no distinction between artery and vein. When the symptoms are this severe, the patient has a significantly increased risk of developing vision loss.[3] Since the retinal lesions categorized can vary from large vascular malformations that affect a majority of the retina to malformations that are barely visible, the lesions can cause a wide range of symptoms including: decrease in visual sharpness, proptosis (the forward displacement of the eye), pupillary defects, optic degeneration and visual field defects.[4] When the visual field is affected due to AVMs, the most common type is homonymous hemianopia.[2] This means that when the visual field is affected, it typically presents unilaterally, but bilateral cases have been reported as well.[7]

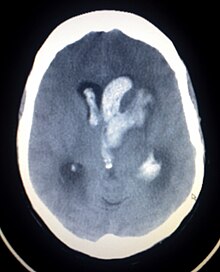

The extent of the central nervous system (CNS) features/symptoms of Bonnet-Dechaume-Blanc Syndrome are highly dependent of the location of the cerebral AVMs and the extent of the malformation.[2][7][4] The most common symptom affecting the CNS is an intracranial hemangioma in the midbrain. [3] Along with hemangiomas, the malformations can result in severe headaches, cerebral hemorrhages, vomiting, meningism, seizures, acute strokes or progressive neurological deficits due to acute or chronic ischaemia caused by arteriovenous shunting.[5]

The distinguishable facial features that result from Bonnet-Dechaume-Blanc Syndrome vary as well. More commonly is faint skin discoloration, nevi and angiomas of the skin.[5] Some patients with this disorder also present with high flow arteriovenous malformations of the maxillofacial or mandibular (jaw) regions.[8] Another facial indicator of this disease is malformations affecting the frontal and/or maxillary sinuses.[4]

Causes

[edit]The syndrome is a congenital disorder (a condition existing at birth) that begins to develop around the seventh week of gestation.[7][9][5] It is caused by abnormal development of vascular tissue which leads to arteriovenous malformations. These malformations affect both the visual and cerebral structures and lead to the development of the the syndrome.[9]

Mechanism

[edit]

A number of examinations can be performed on subjects to investigate the disorder. Neuro-ophthalmic examinations reveal afferent pupillary defects (differences in how a subject’s pupils react to light, see Marcus Gunn Pupil). Funduscopic examinations (examinations of the fundus, located in the eye) reveal arteriovenous malformations.[2] Neurological examinations can reveal hemiparesis (weakness on half of the body) and paresthesias (a sensation of tingling, prickling, or burning of the skin).[2] Fluorescein angiographies can reveal malformations in arteriovenous connections and irregular functions in the veins. Cerebral angiography examinations can reveal arteriovenous malformations in the cerebrum. MRIs can also be used in imaging the brain and can allow visualization of the optic nerve and any possible atrophy. MRI, CT, and cerebral angiography are all useful for investigating the extent and location of any vascular lesions that are affecting the brain.[2][4] This is helpful in determining the extent of the syndrome.

Epidemiology

[edit]The syndrome was first described in 1943 and believed to be associated with racemose hemangiomatosis of the retina and arteriovenous malformations of the brain. It is non-hereditary and belongs to phakomatoses that do not have a cutaneous (pertaining to the skin) involvement. This syndrome can affect the retina, brain, skin, bones, kidney, muscles, and the gastrointestinal tract.[6]

Diagnosis

[edit]Diagnosis commonly occurs later in childhood and often occurs incidentally in asymptomatic patients or as a cause of visual impairment.[3] The first symptoms are commonly found during routine vision screenings. The different examinations mentioned in “Mechanisms” can be used to determine the extent of the syndrome and its severity. Flourescein angiography is quite useful in diagnosing the disease and the use of ultrasonography and optical coherence tomography (OCT) are helpful in confirming the disease.[6]

Treatment

[edit]The treatment for Bonnet-Dechaume-Blanc syndrome is controversial. The first successful treatment was performed by Morgan et. al.[8] They combined intracranial resection, ligation of ophthalmic artery, and selective arterial ligature of the external carotid artery, but the patient did not have retinal vascular malformations.[7]

If lesions are present, they are watched closely for changes in size. Prognosis is best when lesions are less than 3 cm in length. Most complications occur when the lesions are greater than 6 cm in size.[2] Surgical intervention for intracranial lesions has been done successfully. Nonsurgical treatments include embolization, radiation therapy, and continued observation.[4] Arterial vascular malformations may be treated with the cyberknife treatment. Possible treatment for cerebral arterial vascular malformations include stereotactic radiosurgery, endovascular embolization, and microsurgical resection.[2]

When pursuing treatment, it is important to consider the size of the malformations, their locations, and the neurological involvement.[7]

References

[edit]- ^ Liu, Anthony; Chen, Yi-Wen; Chang, Steven; Liao, Yaping Joyce (March 2012). "Junctional Visual Field Loss in a Case of Wyburn-Mason Syndrome". Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology. 32 (1): 42–44. doi:10.1097/WNO.0b013e31821aeefb.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j SINGH, A; RUNDLE, P; RENNIE, I (March 2005). "Retinal Vascular Tumors". Ophthalmology Clinics of North America. 18 (1): 167–176. doi:10.1016/j.ohc.2004.07.005.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kim, Jeonghee; Kim, Ok Hwa; Suh, Jung Ho; Lew, Ho Min (20 March 1998). "Wyburn-Mason syndrome: an unusual presentation of bilateral orbital and unilateral brain arteriovenous malformations". Pediatric Radiology. 28 (3): 161–161. doi:10.1007/s002470050319.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Dayani, P. N.; Sadun, A. A. (18 January 2007). "A case report of Wyburn-Mason syndrome and review of the literature". Neuroradiology. 49 (5): 445–456. doi:10.1007/s00234-006-0205-x. Cite error: The named reference ":3" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d e f Muthukumar, N; Sundaralingam, MP (October 1998). "Retinocephalic vascular malformation: case report". British journal of neurosurgery. 12 (5): 458–60. PMID 10070454. Cite error: The named reference ":2" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c Singh, ArunD; Turell, MaryE (2010). "Vascular tumors of the retina and choroid: Diagnosis and treatment". Middle East African Journal of Ophthalmology. 17 (3): 191. doi:10.4103/0974-9233.65486.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e f Lester, Jacobo; Ruano-Calderon, Luis Angel; Gonzalez-Olhovich, Irene (July 2005). "Wyburn-Mason Syndrome". Journal of Neuroimaging. 15 (3): 284–285. doi:10.1111/j.1552-6569.2005.tb00324.x.

- ^ a b Bhattacharya, JJ; Luo, CB; Suh, DC; Alvarez, H; Rodesch, G; Lasjaunias, P (30 March 2001). "Wyburn-Mason or Bonnet-Dechaume-Blanc as Cerebrofacial Arteriovenous Metameric Syndromes (CAMS). A New Concept and a New Classification". Interventional neuroradiology : journal of peritherapeutic neuroradiology, surgical procedures and related neurosciences. 7 (1): 5–17. PMID 20663326.

- ^ a b Schmidt, D; Pache, M; Schumacher, M (2008). "The congenital unilateral retinocephalic vascular malformation syndrome (bonnet-dechaume-blanc syndrome or wyburn-mason syndrome): review of the literature". Survey of ophthalmology. 53 (3): 227–49. PMID 18501269.