User:Paul August/Giants (Greek mythology)

To Do[edit]

- Look at Tiverios, M. A. (1 January 1982). "Observations on the East Metopes of the Parthenon". American Journal of Archaeology. 86 (2): 227–229. doi:10.2307/504834. JSTOR 504834.

- Add cites to Seneca:

- Hercules Furens 444–445 (pp. 84–85)

- after he [Heracles] defended the gods and spattered their enemies blood over Phlegra,

- Hercules Furens 976–981 (pp. 126–127)

- HERCULES: What is this? The pestilential Giants are in arms. Tityos has escaped the underworld, and stands so close to heaven, his chest all torn and empty! Cithaeron lurches, high Pallene shakes, and Tempe’s beauty withers. One Giant has seized the peaks of Pindus, another has seized Oeta, and Mimas rages fearfully.

- Thyestes 808–809 (pp. 298–299)

- Add cite of Statius, Thebaid 4.34–435 (I pp. 546–547), 8.42–44 (II pp. 198–199).

- Look at the Warburg Iconogrraphic database [1]

- Add Pherec. 3 F 54 for Typhon under Pithecusae

- Add Beazley Archive 1269

- See [2]

- Add cite to b scholia to Iliad 2.783 (also Enceladus): see Kirk, Raven, and Schofield. pp. 59–60 no. 52 for Typhon buried under Etna.

- Read Hardie [in Giants folder]

- Gygantomachy imagery: pp. 85–97, 103, 201–213, others? (Walde, p. 296 cites pp. 85-156)

- Read Yasumura [in Giants folder]

- pp. 44-45, 49-57, 59, 75, 91, 100-1, 171, 173-174, plus other pages for notes and bibiography

- Asterus: 50, 91, 173 n. 44

- GIgantes/Giants: 44-5, 50-57, 171 n. 18, n. 19, 100-1

- Gigantomachy: 59, 75, 91, 174 n. 63

- Switch links for cites to Strabo, book 5 to Internet archive version

- Read Rowell article re Naevius

- Nicander cite?

- Look at Hammond, "Giants" cite.

- Add cite to Durling, p. 495, note to Canto 31.108 "Ephialtes suddenly shook himself"; to Ephialtes?

- Add Aristotle cites

- Add text about the Olympians and their charachteristic weapons (see VIan and Moore 1988, p. 192)?

- Porphyrion = "The purple man, the Phoenician" (king of Athens before Actaeus see Duncker, p. 63

- Look at [3]

- Consider (and incorporate?) Barber 1991, p. 362 n. 5

- Look at The Iconography of Athena in Attic Vase-painting from 440–370 BC [in Giants folder]

- Vian and Moore:

- Cites for Giant articles

- Other cites?

- Add Temple of Athena at Priene?

- Fix cite for Phlegra located in Thessaly

- Get Broken Laughter, re Epicharmus as source for the Giant Pallas as the source Athena's aegis.

- Add speculation on the source for Apollodorus' account:

- Ogden, p. 82

- Review Ogden pp. 84-86 and add cites

- Tzetzes on Lycophron, Alexandra 63

- Get Kästner 1994 (cited by Ridgway p. 54 n. 35)

- Add text on the role of: Zeus, Heracles, Athena, Selene, Nike, Snakes? (Arafat pp. 13-14, 21, 22, 23)?

- Add text about Gaia rising from the ground, and Gaia appealing on behalf of her sons

- Arafat, pp. 25, 26:

- Berlin F2531

- Naples 81521

- Arafat, pp. 25, 26:

- Moore 1985, p. 21 (re pleading)

- Akr 1632

- Akr 2134

- AKr 2211

- Moore 1985, p. 21 (re pleading)

- Weller p. 268 "Ge rising from the ground"

- Ridgway 2000, p. 34: "It should be stressed that many elements attested at Priene recur at Pergamon: Ge rising from the ground ..."

- Figure out Pliny Natural History quote

- Add Snake blazon frequently found on Giants shields (Arafat, p. 25)

- Add cite to "In three early examples, Gaia also appears in the central group, shielded behind Herakles, apparently pleading with Zeus to spare her children." (see Arafat p. 25: )

- Berlin F2531

- Naples 81521 (Arafat, p. 25)

- Siphnian Treasury

- Add Ferrara 2892 in note to Apollodorus' account of Porphyrion being killed by Zeus and Heracles?

- Add to note for Giants wearing skins and fighting w rocks?

- Arafat, p. 27, Beazley Archive:

- Louvre MNB810

- Wurzburg H4729

- Naples 81521

- BM E 165 (Arafat, p 18, Beazley Archive)

- Met 08.258.21 (Arafat, pp 19, 24 Beazley Archive)

- Ferrara 2892 (Beazley Archive)

- Berlin 2531 (Arafat p. 24, Beazley Archive)

- Louvre G372 Beazley Archive 216791

- See also Aristoph. The Birds 1246-1252; Plato, Soph. 246a-b; Euripides, The Phoenician Women 1130.

- Arafat, p. 27, Beazley Archive:

- Add Nonnus Giant descriptions: "huge serpents flowing over their shoulders equally on both sides" (25.206), "Nine cubits high, equal to Alcyoneus" (36.242), look for others

- Nonnus:

- Pelorus (= Pelores?), Cthonion?

- Replace Hyginus reference

- Euryalos and Hyperbios?

- Look at Harrison, p.25

- Look Google search

- Revise when Giants first begin to be depicted not as hoplites wearing animal skins and using rocks as weapons (see British Museum E 47)

- Attic Pallene and the Giants?

- The Giant Rhoetus see:

- Rewrite caption fo Siphnian Treasury detail: Add names of figures:

Siphnian Treasury at Delphi, North frieze, c. 525 BC, detail, left to right: Dionysus, Themis in chariot, Giant with spear, Lion mauling fleeing Giant, Apollo and Artemis, and second fleeing Giant

- Athena is called also Athena gigantoleteira, gigantoletis i.e. the slayer of the giants (See [8])

- [9]

- pages for notes

- Suda, s.v. Γιγαντιᾷ

- Lane Fox, Robin, Travelling Heroes p. 300

- We know of an early poem on the battle of the Titans but we do no happen to know of an early battle of the Giants. No doubt one existed, helping to sort out the details of the war and the catalogue of Gaints, which runs even in modern scholarship to more than fifty names.9

- 9. Waser (1918), 655-759, at 737-59, a remarkable work. So is Vian, LIMC, vol. 4/1 (1988), 191-270, esp. 268-9, partly based on Waser.

- Naples 81521 (Fomerly Naples H2883)

- Add vase record at Enceladus, Porphyrion, Mimas? (add to those three articles?)

- Expand symbolism section with other uses of "Gigantomachy imagery as a positive metaphor for pursuits of scientist", see Green p. 138

- Add Christian POV to symbolism section, see Brumble, p. 138

- Lead: Rewrite lead to reflect article; expand last paragraph; add motivation.

- Yasumura

- pp. 49–58 (see Amazon for page numbers)

- Copy text for Schol. Pind. Nem 1.101 (compare w Gantz, p. 449)

- Incorporate Schol. Pind. Nem 1.101 for prophecy concerning need for Heracles and Dionysos, and location of the battle at Phlegra.

- Asterius/Asterus

- Meropis and the Meropes

- Incorporate OCD: "The Giants were defeated and believed to be buried under the volcanoes in various parts of Greece and Italy, e.g. Enceladus undet Aetna. Bones of prehistoric animals were occasionally believed to be the bones of giants."

- Add the hundred-handers as also being confused with the Giants: Briareus (also called Aigaion/Aegaeon), Cottus and Gyges/Gyes?

- Incorporate Lyne, pp. 167–168

Find[edit]

Waser, O., RE Suppl. 3, 737-759 (cited by Vian and Moore, for list of Giant names)

- Brill’s New Pauly: Encyclopaedia of the Ancient World

Otto Waser: Giganten. In: Paulys Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft (RE). Supplementband III, Stuttgart 1918, Sp. 655–759 (Nachträge und Berichtigungen: ebenda 1305f.).

Get library books[edit]

Boston College[edit]

- Shapiro, H. Alan, Art and Cult under the Tyrants in Athens 1989

- Athena's Peplos: pp. 38-40

- Bapst Library Art Stacks

BU[edit]

MFA[edit]

- Vian, Francis (1951), Répertoire des gigantomachie figurées dans l'art grec et romain (Paris)

- Look at

- Art of the Ancient World Library

- Vian, Francis (1952), La guerre des Géants: Le mythe avant l'epoque hellenistique, (Paris)

- pp. 77-79: Polybotes v. Poseidon

- pp. 95-97: Zeus, Heracles, Athena

- pp. 262ff: Asterius

- Art of the Ancient World Library

Tufts[edit]

Look at/Read[edit]

- Grummond, From Pergamon to Sperlonga: Sculpture and Context (Hellenistic Culture and Society)

- Amazon

- Google Books

- Re Attalids (see [11])

- Beazley, J. D., Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters 2nd edition (Oxford, 1963) (=ARV 2) (at Tufts)

- Burkert mentions

- Castriota pp. 139 ff.

- Fontenrose, Python: A study of delphic myth and its origins [12], in particular: pp. 239 ff.

- Frazer's notes to Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer,

- Frazer (Vol II), note to Pausanias 1.2.4 "Poseidon on horseback hurling a spear at the giant Polybotes" pp. 48–49

- Hard, pp. 86 ff.

- Harpers Dictionary "Gigantes"

- Hurwit new pages 121-124 (in "Giants" folder)

- Lechelt (in Giants folder)

- Mayor, Adrienne Mayor, The First Fossil Hunters: Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and Myth in Greek and Roman Times [13]

- Mitchell, pp. 573–590

- Moore 1977, "The Gigantomachy of the Siphnian Treasury" [in Giants folder]

- Moore 1979, "Lydos and the Gigantomachy" [In Giants folder]

- Moore 1989, "Giants at the Getty, Again" pp. 33 ff.

- Ogden, Daniel, Drakon: Dragon Myth and Serpent Cult in the Greek and Roman Worlds p. 82 ff.

- Pollitt 1986, "Art in the Hellenistic Age" [In "Giants" folder)]

- Queyrel (in Giants folder)

- Ridgway, B.S., Hellenistic Sculpture II [In "Giants" folder)]

- Look at works cited p. 48 n. 6

- Rose, H.J. A andbook of Greek Mythology pp. 45 ff.

- Simon 1975, "Pergamon Und Hesiod" [In "Giants" folder)]

- Vian, Guerre (at MFA)

- Guerre: Polybotes v. Poseidon pp. 77-79

- Vian, Répertoire (at MFA)

- Vian & Moore 1988, "Gigantes" [In "Giants" folder)]

- Literary sources: 191-196

- Pergamon Altar: 202-207, especially 207 (for names of Giants)

- Walters pp. 15 ff.

- Wilkinson, pp. 141–142

Copy[edit]

- Hard

- Finish copying Ogden quotes pp. 84-86

- Samelson

Other articles[edit]

- Rewrite Gigantomachy frieze section of Pergamon Altar

- Porphyrion To Do's

- Enceladus To Do's

- Alcyoneus To Do's

- Fix Philostratus articles

- Britannica Flavius-Philostratus, Philostratus-the-Lemnian

- See also [14]

- Britannica 1911 Philostratus

- See Peck Rhoecus

New Text[edit]

Apollodorus[edit]

When the Giants had been finally overcome Gaia, according to Apolodorus, even more enraged, than she had been after the defeat of the Titans, "had intercourse with Tartarus and brought forth Typhon".

Notes[edit]

Giants[edit]

Enormous and monstrous human-like creatures.

- Agrius and Oreius, when a woman was cursed by Aphrodite to fall in love with a bear, the twin giants were born, they look half-man, half-bear.

- Chrysaor, a son of Medusa and Poseidon, sometimes said to be a giant, he was born alongside Pegasus by Perseus slashing their mother's head.

- Echidna, a giant monstrous women with upper body of a beautiful nymph, while the lower is a giant serpent, she is the wife of Typhon.

Gigas[edit]

The term gigas, used more broadly:

LSJ "gigas"

- Γίγας [ι^], αντος, ὁ, mostly in pl., Giants,

- A.“ὑπέρθυμοι” Od.7.59; Κύκλωπές τε καὶ ἄγρια φῦλα Γιγάντων ib.206; οὐκ ἄνδρεσσιν ἐοικότες “ἀλλὰ Γίγασιν” 10.120; “γ. γηγενέται” Hes.Th.185, cf. E.Ph.128 (lyr.); of Capaneus, A.Th.424.

- II. as Adj., mighty (γίγαντος: μεγάλου, ἰσχυροῦ, ὑπερφυοῦς, Hsch.), “Ζεφύρου γίγαντος αὔρᾳ” Id.Ag.692 (lyr.), cf. Eurytus (PLG3.639).

Vian and Moore 1988, p. 192.

- Note finally that the term G. was used in a broad sense to refer to -» Pallantides (Soph. Aigeus, TrGF IV F 24, 6-7), the men of the Golden Age (Télékleides Amphictyons, CAF I frg. 1, 15) or the Zéphyr (-» Zephyros) (Aischyl. Ag. 692). As in Homer (Od. 10, 120), it also serves to characterize arrogant and wicked warriors like -» Kapaneus (Aischyl Septem 423-425; Eur. Phoen 127-130) or -» Pentheus (Eur. Bacchae 538-544).

- Pallantides: Sophocles, Aigeus (TrGF IV F 24, 6-7)

- Lloyd-Jones, pp. 20–21

- she sailed the sea before the breath of earth-born [γίγαντος] Zephyrus.

- Yes, may the gods so grant success to this man. Capaneus is stationed at the Electran gates, another giant of a man, greater than the one described before. [425] But his boast is too proud for a mere human, and he makes terrifying threats against our battlements—which, I hope, chance will not fulfil! For he says he will utterly destroy the city with god's will or without it, and that not even conflict with Zeus, though it should fall before him in the plain, will stand in his way. [430] The god's lightning and thunderbolts he compares to midday heat. For his shield's symbol he has a man without armor bearing fire, and the torch, his weapon, blazes in his hands; and in golden letters he says “I will burn the city.” [435] Against such a man make your dispatch—who will meet him in combat, who will stand firm without trembling before his boasts?

- What rage, what rage does the earth-born race show, and Pentheus, [540] once descended from a serpent—Pentheus, whom earth-born Echion bore, a fierce monster, not a mortal man, but like a bloody giant, hostile to the gods.

Named Giants[edit]

- Argos: p. 115

- Orion: p. 182

- Pelorus: Add named by Hyginus, possibly named ([Pel]oreus) on Siphnian Tr. & Nonnus

- Add Hyginus' list (or certain mentions)?

as listed in my "Giant Names":

- Abseus

- Agrius

- Astraeus

- Coeus

- Colophomus

- Emphytus

- Enceladus

- Ephialtes

- Eurytus

- Iapetus

- Ienios

- Menephiarus

- Ophion

- Otos

- Palaemon

- Pallas

- Pelorus (= Peloreus?)

- Polybotes

- Rhoecus/Phaecus

- Theodamus

- Theomises

- Typhon

Look at [15]

In art[edit]

Sixth century BC[edit]

In art[edit]

- Walters pp. 15 ff.

- Wilkinson, p. 142

- Hurwit, p. 31

- Gigantomachies were thus added constantly to the narrative inventory of the Acropolis. the theme undergoing nearly constant reinterpretation in a variety of media. No better example exists of how a particular theme edures over time — of how the imagery of the Classical Acropolis echoes the magery of the Archaic or the Hellenistic the Classical — or how the same theme could be seen in different versions, in different inflections, at any one time.

Sculpture[edit]

Siphnian Treasury c. 530–525 BC[edit]

Perseus: Delphi, Siphnian Treasury Frieze--North (Sculpture)

- [Porphy]rion

LIMC Gigantes 2

The Siphnian Treasury: The North side of the frieze (The Gigantomachy - Hall V)

Arafat

- p. 169

- The Gigantomachy had long been open to a particular city to put its stamp on, the unorthodox names on the Siphnian treasury at Delphi being a prime example

Brinkmann

- p. 128 n. 194

- Athena ist durch Gegnerzahl and Komposition vor den übrigen hervorgehoben. Asterias ist ihr Gegner im mythos. Zum Gedenken an seinen Tod wurden in Athen die Panathenaen eingericht (Arist., fr 637 Rose. Vgl. VIAN, Guerre, 262ff., passim. Es wäre zu überlegen, ob die herausragende Rolle der Athena am Fries als Verbeugung vor der Stadt Athen zu verstehen ist. Ubrigens ist Athena auch durch die farbliche Fassung ihres Gewandes hervorgehoben. Dazu werde ich an späterer Stelle Stellung nehmen. Beachte andererseits Bronzereste am Ohr des Astarias, die von I.A Coste-Messeliere als Pfeil der Letoidengruppe gedeutet worden sind, Au Mussee, 313.

- [Google translate: Athena is highlighted by opponents number and composition over the other. Asterias is her opponent in the myth. To commemorate his death, the Panathenaen were in Athens arranged (Arist., fr 637 Rose. See. VIAN, Guerre , 262ff., Passim . It could be considered whether the outstanding Note is the role of Athena on the frieze to understand as bowing to the city of Athens. Incidentally Athena is also highlighted by the colored version of her gown. for this I will comment later. on the other hand bronze groups at the ear of the Astarias that of IA Coste-Messeliere have been interpreted as the arrow Letoidengruppe, Au Mussee, 313th

Stewart

- p. 128

- dated absolutely to c. 525: this is our first fixed date for any archaic sculpture.

Schefold

- p. 60 [Can be seen by linking from my laptop]

- 67–9 Gigantomachy. North frieze of Siphnian Treasury at Delphi, towards 525.

- p. 62

- In the midst of the Giants is the mysterious Themis group — Themis was the time-honoured mistress of the sanctuary at Delphi (see above, p. 9, and below, p. 203). For the artist she is identified with the mother of the gods (as oppossed to Ge, the mother of the Giants): she appears here in the guise of Kybele, the Asiatic Mistress of Anomals, and her chariot is drawn by a team of lions (fig. 67).

Morford

- p. 73

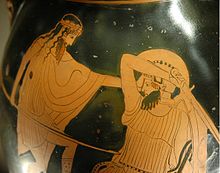

- [caption:] Gigantomachy. Detail from the north frieze of the treasury of the Siphnians at Delphi, ca 525 B.C.; marble, height 25 in. From left to right two giants attack two goddesses (not shown); Dionysus, clothed in a leopardskin, attacks a giant; Apollo and Artemis chase a running giant; corpse of a giant protected by three giants. The names of all the figures were inscribed by the artist. The giants are shown as Greek hoplites—a device both for making the battle more immediate for a Greek viewer and for differentiating between the Olympians and the giants.

Temple of Apollo at Delphi c. 513 BC–c. 500 BC[edit]

- Perseus: Delphi, Temple of Apollo, West Pediment (Sculpture)

- LIMC Gigantes 3

- Schefold, p 64

- Neer, Richard T., "Delphi, Olympia, and the Art of Politics" in The Cambridge Companion to Archaic Greece Cambridge University Press 2007. ISBN 9781139826990. p. 247

- The Splendid pedimental decoration of this building dated circa 510, is in the Delphi Museum

- p. 258: References [link viewable from my laptop]

- Stewart, pp. 86–89

- Euripides, Ion 205–218

- Vian and Moore, pp. 198–199 no. 3.

Megarian Treasury[edit]

- Megarian Treasury Pediment c.510–500 BC

- Post, pp. 148–149

- Pollitt 1990, pp. 22–23

- Pausanias, 6.19.12–14

- Frazer,

- ASCA Digital Collections, Megarian Treasury

Temple F at Selinous[edit]

- Gardner, pp. 164–165

East pediment of the Peisistratid Temple of Athena on the Acropolis (510/500 BC)[edit]

- Schefold, pp. 64–67

- Hurwit, p. 30 Archaios Neos

East Metopes of the Parthenon (completed in 438 BC)[edit]

Athena Parthenos[1][edit]

- Pliny, Natural History 36.4

- but it is to the shield of this last statue that we shall draw attention; upon the convex face of which he has chased a combat of the Amazons, while, upon the concave side of it, he has represented the battle between the Gods and the Giants.

- Pliny, Natural History 36.4

- Arafat 1986

- Arafat 1990

- p. 25

- The vault of heaven is one feature of the depiction which has led to many attempts to relate this vase [Naples 81521] to the Gigantomachy of the interior of the shield of the Athena Parthenos, mentioned by Pliny (Natural History 36.18).34

- 34 The most comprehensive discussion is that of von Salis, JdI 55 (1940), 90-169; most recently, K. W. Arafat, BSA 81 (1986). 1-6.

- The vault of heaven is one feature of the depiction which has led to many attempts to relate this vase [Naples 81521] to the Gigantomachy of the interior of the shield of the Athena Parthenos, mentioned by Pliny (Natural History 36.18).34

- p. 169

- A more likely inspiration is the Gigantomachy of the interior of the shield of the Athena Parthenos, which is reflected more closely on 1.82 [Naples 81521] than on any other vase.

- p. 25

- Arafat 1990

- Cook, p. 56

- Vases (2) [Louvre MNB810] and (3) [Naples 81521] presuppose a famous original, probably the Gigantomachy painted on the inside of the shield of Athena Parthénos. The semicircular band ... which on vase (3) denotes the arch of heaven may well perpetuate the rim of Athena's shield. ...

- Cook, p. 56

- Dwyer

- p. 295

- Judging from surviving monuments that reflect the shield of Athena Parthenos, the giants were arrayed within a lower circle (or sphere) against the Olympians in an upper or outer circle. The giants fought with great stones, attempting either to hurl them or pile them atop one another in effort to reach the heavens.

- p. 295

- Dwyer

- Robertson, pp. 106–107

- One of the little copies of the shield of Athena Parthenos has traces of the painted Gigantomachy inside. A group can be faintly made out which recurs on a number of vases with the subject painted in Athens around 400, a time when there is considerable evidence of artistic nostalgia (cf. below, p. 116). The vase-pictures vary a good deal, but a distinctive principle of composition is common and surely derives from the original: the gods, high in the picture, are fighting down towards us, while the Giants tend to have their backs to us or to retreat in our direction (fig. 147 [Louvre MNB810]).

- 147 Neck-amphora (not, as long believed, from Melos; probably from Italy). Attic red-figure: Gigantomachy. Ascribed to Suessula Painter. About 400 B.C. H., with lid that does not fit.

- Robertson, pp. 106–107

- Louvre MNB810

Temple of Athena at Priene[edit]

- LIMC Gigantes 26

- Vian and Moore 1988, p. 207 no. 26, p. 208 pl. 1172

- Carter, J. C. The Sculpture of the Sanctuary of Athena Polias at Priene London 1983.

- Pollitt 1986, Art in the Hellenistic Age, pp. 242-244, figs 258-259.

- Ridgway, B. S., Hellenistic Sculpture I

- p. 164

- The Altar of Athena at Priene has been recently studied and redated.16

- p. 164

- p. 202 n. 16

- 16 Priene Altar: Carter, Priene [The Sculpture of the Sanctuary of Athena Polias at Priene], 181-209, pls. 29-32. See also J. C. Carter, "The Date of the Altar of Athena at Priene and its Reliefs," in Bonacasa and Di Vita, eds., 3, 748-764, pls. 114-115; although this article appeared after Carter's book, it was obviously written before, and therefore some of the statements are at variance with the text of Priene; this later publication ought to be taken as definitive. For a review in favor of the traditional mid second-century date see, e.g., R. Fleischer, Gnomon 57 (1985) 344-352, esp. 347-348.

- p. 202 n. 16

- Ridgway, B. S., Hellenistic Sculpture II

- p. 34

- The tradition of anguiped Giants existed well before the Hellenistic period, not only on vases, but also, as it seems assured, on the coffers of the Athenaion at Priene, now seen to predate the Altar [at Pergamon]. It should be stressed here that many elements attested at Priene recur at Pergamon: Ge rising from the ground, a goddess (Kybele) riding side-saddle on a lion, another lion (probably with Dionysos) biting a Giant on the shoulder, Athena's opponent with snaky legs but also with wings.45

- p. 34

- p. 55 n. 45

- 45 Priene coffers: Carter 1983, 44-180 (cat. 1-67 on pp. 103-80). Coffer with Ge: cat 27; Kybele on lion: cat 14 ... Athena and opponent: cat 31-32. ...

- p. 55 n. 45

- "Morphing Monsters" 2§3

- 2§3 While snake-legged Giants are produced early in Etruria, the human form Gigantomachy became a popular motif in mainland Greece from the sixth century BCE. It is this motif of a human form Giant that traveled to Anatolia during the fourth century BCE during the expeditions of Alexander the Great. One of the first examples of the Gigantomachy comes from the Temple of Athena at Priene in modern day Turkey, which was dedicated by Alexander in 334 BCE.[18] Most of the Giants here are portrayed as nude savages who are fully human and cowering at the feet of the gods, yet one Giant has snake-legs and wings (see Figure 4). After Priene, Giants are almost always depicted as anguipedes throughout Asia Minor.

- "Morphing Monsters" n18

- The Ionic architect, Pythius, who also designed the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, designed innovative coffers carved with the battle between the Gods and the Giants located on the ceiling of the peristyle. Vian and Moore 1988:207, Cook and Spawforth 2003:1209, Richmond et al. 2003:1247.

Pergamon Altar (2nd century BC)[edit]

Arafat

- p. 169

- The Gigantomachy had long been open to a particular city to put its stamp on, the unorthodox names on the Siphnian treasury at Delphi being a prime example, and the altar of Zeus at Pergamon a later one.

Kleiner

- p. 155 FIG. 5-78

- 5-78 Reconstructed west front of the Altar of Zeus, Pergamon, Turkey, ca. 175 BCE. ... The Gigantomachy frieze of Pergamon's monumental Altar of Zeus is almost 400 feet long.

- p. 156 FIG. 5-79

- 5-79 Athena battling Alkyoneos, detail of the gigantomachy frieze, Altar of Zeus, Pergamon, Turkey, ca. 175 BCE. Marble, 7' 6 high.

Mitchell

- p. 575

- Fig. 235 Reconstruction of the Great Altar at Pergamon by R. Bohn. Temples of Athena Polias and of Augustus in the background.

- p. 582

- The names of the giants were carved in smaller letters on the cornice below the frieze. Of these only five are preserved complete,—Cthonophylos, Erysichthon, Ochthaios, Obrimos, and Udaios. None of them are properly giants, although the latter is known to have been akin to themfrom his earth-born nature. Of other names, eleven fragments have been found.

- p. 584

- In the older poetry, sculpture and vase-paintings of the Greeks, we find the giants always represented simply as mortals, fully armed. Thus the appear in the Megara treasury pediment at Olympia (p. 211), dating from the sixth century; and thus down even to metopes of the Parthenon. In vase paintings of the fourth century, however these giants have thrown off their armor, and become wild in appearence, and have shaggy disordered hair, and use for weapons rocks and tree-trunks. By the third century, on certain terra-cottas, these enemies with a human body on snaky coils; but, as far as is known, they are thus represented in sculpture for the first time in these reliefs from Pergamon.

Queyrel 2005, L'Autel de Pergame [in "Giants" folder]

Ridgway, Brunilde Sismondo 2000, Helenistic Sculpture II [Google has the text of this work under a different work by Ridgway]

- p. 32

- Yet some sculptors' names have come down to us, inscribed on the base molding below the frieze slabs, and clearly distinguished from those naming the Giants, on the same architectural element,34 by their lower level and the added verbs, ethnics, and patronymics, when perserved. The gods' names, in turn, were engraved on the cavetto molding above the dentils, or, in the case of Ge, on the background next to her head.35

- p. 33

- over one hundred named figures [on the Pergamon Altar]

- p. 34

- It should be stressed that many elements attested at Priene recur at Pergamon: Ge rising from the ground ..."

- p. 54

- 34 On the walls of the podium flanking the stairs (the German Risalit ... ), where the bottom molding was omitted, the sculptors' names were inscribed on the cornice, and the Giants' on the background of the frieze, between the figures.

- 35 At current count, 25 gods' names are preserved, although others can be conjectured; a drawing of the Gigantomachy slabs in Pollitt 1986, 96-97, distinguishes among degrees of certainty for various identifications. Fehr 1997, 61 n. 13, mentions that the identification of 33 (= over 50 percent of the ca. 60 fighting deities) is assured or non-cntroversial. He further breaks down the totals to 32 goddesses and 21 gods (cf. Simin 1975, who fills up the gaps and counts 38 goddesses and 24 gods).

- To the 17 Giants' names listed by Smith 1991, 164, that of Porphyrion can now be safely added (Kästner 1994) on the basis of a new fragment joining a previously known one; it can be shown to belong to Zeus' opponent with hollow eyes, as previously hypothesized, although Simon 1975 had suggested Typhon; see her chart on rear foldout pl. 1 (approx. p. 69).

- pp. 59–60 n. 59 [This link can be viewed from my laptop]

- 59. The quotation (originally in French) is from LIMC 1, s.v. Alkyoneus, 564 no. 33 (R. Olmos/L. J. Balmaeseda). Identification is provided by a fragmentary inscription, ...]ΝΕΥΣ, that may belong to the scene. Harrison, in her review of Simon 1975 (supra, n. 6), points out that [p. 60] Athena is pulling the Giant toward, rather than away from, his mother; that wings are unusual for Alkyoneus; and that Enkelados, "whose name evokes the sound of rushing winds," would be a better identification. Simon's argument (pp. 22, 44) that both Athena and Zeus are given the two "immortal" Giants as opponents, is rendered invalid by recent integration of Porphyrion's name instead of Typhon's (supra, n. 35). Simon explains Alkyoneus' four wings as an indication that the goddess can overcome her opponent only in the air (p. 22). But the Greek name alkyon means kingfisher, the sea bird who might have inspired Alkyoneus' wings.

Ridgway, Brunilde Sismondo, 2005 Review of François Queyrel, L'Autel de Pergame. Images et pouvoir en Grèce d'Asie. Antiqua vol. 9. in Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2005.08.39

- A good portion of the book is taken by superb descriptions of the Gigantomachy and Telephos Friezes, accompanied by new detailed drawings (by Florence André). The outer frieze is more or less established in its general sequence and only individual identities remain controversial. Q. [Queyrel] proposes many new ones, especially on the North side where he locates Hermes and Hephaistos,5 as well as the three Gorgons: Medusa, Euryale, Stheno, and the three Moirai: Lachesis, Clotho, Atropos. This last is the spectacular deity hurling an enigmatic vessel circled by a snake (figs. 67-68). She is traditionally known as Nyx, but Q. believes that Night should be recognized in the velificans female next to Rhea/Cybele on the South (fig. 53). Two "digressions" ("La véritable Nyx," pp. 63-64; and "La pseudo-Nyx," pp. 72-73) convincingly argue both cases. A Table (pp. 76-78) summarizes the main identifications that have been proposed for each figure, with Q.'s new ones highlighted by bold type. The line drawings (fig. 33, pp. 50-51) include new names for both Gods and Giants, as well as the plan of the present display in Berlin. Two more Tables (p. 52) list the few preserved names of divinities inscribed on the upper molding, and those of Giants on the lower molding of the frieze, together with the mason's marks appearing on the relevant blocks.

- Several details in the description are either novel or unfamiliar. Added fragments show a Giant flipped into the air by a ketos accompanying Poseidon. Demeter (now positively located) uses two torches against Erysichton. A flaming torch is also used by Eos who rides to the help of Kadmilos (one of the Kabeiroi) in hard combat with a monstrous bull-Giant (figs. 50-52). Athena, in pulling Alkyoneus by the hair not only removes him from his mother Ge but also (p. 54) exposes his body to the arrows of Herakles (now mostly fragmentary) who stands behind Zeus. Another archer is Apollo, on the same East side, who has hit in his left eye the reclining Giant now identified by inscription as Oudaios (not Ephialtes; pp. 55-56). The young Giant grabbed by Doris, albeit beardless, surprisingly wears a mustache (p. 67, fig. 59) -- the only such example of facial hairstyle, to my knowledge.

Simon 1975, Pergamon und Hesiod (in "Giants" folder)

Pergamon Altar Gigantomachy Viewer

Attalid dedication on the Acropolis[edit]

- Gardner p. 495

- Another series ...

- Gardner p. 495

Athena's peplos[edit]

Plato

- Euthyphro 6b–c

- [6b] ... And so you believe that there was really war between the gods, and fearful enmities and battles and other things of the sort, such as are told of by the poets and represented in varied designs [6c] by the great artists in our sacred places and especially on the robe which is carried up to the Acropolis at the great Panathenaea? for this is covered with such representations. Shall we agree that these things are true, Euthyphro?

- The Republic 2.378c

- [378c] if we wish our future guardians to deem nothing more shameful than lightly to fall out with one another; still less must we make battles of gods and giants the subject for them of stories and embroideries,1 and other enmities many and manifold of gods and heroes toward their kith and kin.

- 1 On the Panathenaic πέπλος of Athena.

Barber 1991, Prehistoric Textiles"

- p. 361

- Every year the Athenians held a festival of thanksgiving to Athena. their patroness; and every fourth year they held a particularly large version of the festival—the Great Panathenaia. The celebrations included atheletic events, the most unusual of which were a torch race (Parke 1977, 37, 45, 171-72) and the Pyrrhic dance (according to legend the dance done by Athena to celebrate a victory of the gods over the giants: ibid., 36), as well as a huge procession through the city to bring Athena her new dress (see Pfuhl 1900; Deubner 1932; Davidson 1958; Mommsen 1968, 116-205; etc.). ...

- p. 362

- ... So we glean the additional information that one didn't weave just any old giants but specifically the Battle of the Gods and the Giants in which the gods led by Zeus and Athena, put down a terrifying and nearly catastophic insurrection of those awesome monsters who rumble around where they have been chained under the earth, and who occasionally escape and erupt forth to challenge the gentle order of the gods.5

- p. 380

- From the story of "Demetrios the Savior" [see p. 362] we got the impression, strengthened elsewhere, that the subject of the peplos had to do with those who had saved Athens, Athena and Zeus being foremost because of their parts in the Gigantomachies. The peplos would seem to be an offering to the goddess specifically in thanks for saving her people from the terrible threat of the Huge Ones—and a repeated reminder to her never to let them escape again.

- p. 381

- Those who have worked extensively with myths generated from catastrophe agree that this particular story [Hesiod, Theogony 678-86, 693-705)] is a roughly but rationally decipherable, metaphoric account of a volcanic eruption (cf. Rose 1959, 44-45), and most likely, at least in part, of the cataclysmic destruction of Thera that occurred in the 15th century B.C., which was one of the largest and ludest eruptions the huma race has ever witnessed (cf. Luce 1969, 58-95, esp. 74-84), Surely this eruption above all others would call forth relief at salvation and a desire never to have to go through such cosmic terror again. Athens after all, had a ringside seat. Giants, Titans and such, as metaphors for and personifications of the volcanic forces, are therefore exactly appropriate symbols to commemorate such an awesome event.

- The Greeks themselves placed the origins of their festival back in Mydenaean times: some parts were ascribed to Theseus and some to the earlier indigeneous inhabitants, who were said to have set it up in honor of the death of a giant named Asteros ("Bright One" or "Glitterer"), although some of the games were established much later (see Davison 1958, 32-35, for full references).

- ...

- Are we, then, to imagine the ruler of Athens (whether Theseus or another) desperately and solemly vowing to Athena—as the volcano across the way was blowing its heart out in an eruption that would make Mount Saint Helens, Kilaueia, and even Krakatoa look small—that if the devine Protectress would save him and his people from this unimaginably devastating monster, he would provide her with the finest he could offer: huge sacrifices, the most expensive of new dresses, and a grand celebration and victory dance in her honor, every year in perpetuity?

- Athens, unlike many an Agean site, survived the disaster. That would have been proof enough that Athena and Zeus had cared about and saved their people. to commemorate the event symbolically in dance, in fire rituals, and through the age-old local craft of weaving—does not seem so strange.

Barber 1992, "The Peplos of Athena"

- p. 103

- According to ancient authors, one of the central features of the Panathenaic Festival was the presentation to Athena of a woven, rectangular woolen cloth called a peplos, always decorated with the fiery Battle of the Gods and Giants. Presenting a textile seems appropriate enough, for Athena was, among other things, the goddess of weaving. But there clarity stops. Who wove it and how often? Was a new one made every year, or only every four years for the Greater Panathenaia?

- ...

- Bronze Age Background

- The Classical Greeks had inherited a 7000-year tradition of weaving, ...

- p. 104

- By 1500, when the Mycenaean Greeks were constructing citadels, ...

- With this tradition in mind, we must tackle the questions surrounding the making of the sacred peplos of Athena. Fancy weaving in the fifth-century was not a late and newly acquired art, for professionals only, but a household craft that had been at the core of Agean culture for millennia. In fact, given how old the tradition of ornate weaving was in the Aegean and how important it had been to the Bronze Age economy, it would be strange if the main religious customs surrounding weaving were not old and deeply rooted.

- p. 112

- We know that the peplos was a rectangular woolen cloth described as showing the figures of Athena and Zeus leading the Olympian gods to victory in the epic Battle of the Gods and Giants (see for example the lines from Hecuba quoted on p. 103).

- p. 117

- Select women of Athens wove a normal-sized robe destined to dress the cult statue every year, whereas professional male weavers seem to have woven a cloth every fourth year for pay—a sail-peplos that was much larger, fancier, newer in tradition than the women's, and not intended for the statue. Both textiles, however, seem to have displayed in their threads Athena's part in the Battle of the Gods and Giants, as a renewed thank-offering to the patroness of Athens for saving the city from destruction. ... All this evidence evidence strongly suggests that the entire ritual of presenting Athena with an ornate new dress was a local relic of the Bronze Age.

- Regardless of the origins of presenting a robe every year to Athena ... the ritual clearly held an integral place in the lives of the Athenian citizens, ... celebrating Athena and thanking her for one of her most famous deeds, the destruction of the world-threqatening giants.

Simon 1991

- p. 23

- The festival of the Panathenaia, celbrated in honor of Athena, was surely of Bronze Age origin.70 Its main rite, the offering of a garment, is repeatedly represented in Mycenean frescoes, and Homer describes the procession of Trojan women putting a peplos on Athena's knees (Iliad 6.288–304). The unification of Attika by Theseus was the virtual prerequisite for the Panathenaia. but the Athenians ascribed the foundation of their main festival to Erichthonios-Erechtheus. Since that celebration, however, was reorganized several times—for example, in 566—Theseus could be thought to have been its first reorganizer.

Other:

- Håland Athena’s Peplos: Weaving as a Core Female Activity in Ancient and Modern Greece

- Lefkowitz p. 96 ff., together with: pp. 88–89

- Munn, p. 291 (See sources)

- Schnusenberg, pp.135–137

- Robertson, p. 63

Look at:

Get:

- Shapiro, H. Alan, Art and Cult under the Tyrants in Athens pp. 38–40 Boston College

Art: text from Gigantomachy[edit]

- A temple at Phanagoreia commemorated Aphrodite's victory over some Giants. She drove them into a cave, where Heracles slaughtered them.

Gigantomachy and the Acropolis[edit]

Hurwit pp. 30–31

In religion, cult[edit]

?

Chronology[edit]

Hansen, p. 178:

- "According to Apollodorus, the Gigantomachy took place after the Titanomachy and before the combat of Zeus and Typhon. ("When the gods had overcome the giants, Earth, still more enraged, had intercourse with Tartarus and brought forth Typhon ..." (Apoll. 1.6.3)

Symbolism, meaning and interpretations[edit]

Statius?

- Look at/ incorporate Lovatt, pp. 114 ff.

- See also McNeils [20]

See Hardie 2014, p. 101.

Hardie 1986, pp. 85–156, Hardie 1993 (See Walde p. 296)

See also Cicero, Font. 30 (Gauls), Livy 3.2.5 (Aequi), Cic. Verres 2.4.72, Livy 21.63.6 (see Chaudhuri, p. 7 note 22)

See also Cicero Har. resp. 20 and others: Powell p.110

Other Virgil cites:

Walde, p. 296 Chaudhuri, pp.169 ff.

New References[edit]

New Notes[edit]

- ^ Wilson, p. 559.

- ^ Cunningham, p. 113; Kleiner, p. 156 FIG. 5-79; Queyrel, pp. 52–53; Ridgway, Brunilde Sismondo 2000, p. 39, pp. 59–60 n. 59. Supporting the identification of this Giant as Alcyoneus, is the fragmentary inscription "neus", that may belong to this scene, for doubts concerning this identification, see Ridgway.

Sources[edit]

Ancient[edit]

Archaic (c. 800 - 500 BC)[edit]

c. 750 - 650 BC Homer[edit]

- 14.250–256

- on the day when the glorious son of Zeus [Heracles], high of heart, sailed forth from Ilios, when he had laid waste the city of the Trojans. I, verily, beguiled the mind of Zeus, that beareth the aegis, being shed in sweetness round about him, and thou didst devise evil in thy heart against his son, when thou hadst roused the blasts of cruel winds over the face of the deep, and thereafter didst bear him away unto well-peopled Cos, far from all his kinsfolk.

- 7.56–63

- Nausithous at the first was born from the earth-shaker Poseidon and Periboea, the comeliest of women, youngest daughter of great-hearted [μεγαλήτορος, LSJ: "greathearted"] Eurymedon, who once was king over the insolent [ὑπέρθυμος, LSJ: "overweening"] Giants. [60] But he brought destruction on his froward [ἀτάσθαλος, LSJ: "reckless, presumptuous, wicked"] people, and was himself destroyed. But with Periboea lay Poseidon and begat a son, great-hearted Nausithous, who ruled over the Phaeacians; and Nausithous begat Rhexenor and Alcinous.

- 7.199–207

- "But if he is one of the immortals come down from heaven, [200] then is this some new thing which the gods are planning; for ever heretofore have they been wont to appear to us in manifest form, when we sacrifice to them glorious hecatombs, and they feast among us, sitting even where we sit. Aye, and if one of us as a lone wayfarer meets them, [205] they use no concealment, for we are of near kin to them, as are the Cyclopes and the wild tribes of the Giants.”

- 10.120

- Then he raised a cry throughout the city, and as they heard it the mighty Laestrygonians came thronging from all sides, [120] a host past counting, not like men but like the Giants.

c. 750 - 650 BC Hesiod[edit]

- 50–52

- And again, they chant the race of men and strong [κρατερός LSJ: "strong, stout, mighty"] giants, and gladden the heart of Zeus within Olympus,—the Olympian Muses, daughters of Zeus the aegis-holder.

- 173 ff.

- So he said: and vast Earth rejoiced greatly in spirit, and set and hid him in an ambush, and put in his hands [175] a jagged sickle, and revealed to him the whole plot. And Heaven came, bringing on night and longing for love, and he lay about Earth spreading himself full upon her.1Then the son from his ambush stretched forth his left hand and in his right took the great long sickle [180] with jagged teeth, and swiftly lopped off his own father's members and cast them away to fall behind him. And not vainly did they fall from his hand; for all the bloody drops that gushed forth Earth received, and as the seasons moved round [185] she bore the strong Erinyes and the great [μεγάλους] Giants with gleaming armour, holding long spears in their hands and the Nymphs whom they call Meliae2 all over the boundless earth. And so soon as he had cut off the members with flint and cast them from the land into the surging sea, [190] they were swept away over the main a long time: and a white foam spread around them from the immortal flesh, and in it there grew a maiden. First she drew near holy Cythera, and from there, afterwards, she came to sea-girt Cyprus, and came forth an awful and lovely goddess, and grass [195] grew up about her beneath her shapely feet. Her gods and men call Aphrodite, and the foam-born goddess and rich-crowned Cytherea, because she grew amid the foam, and Cytherea because she reached Cythera, and Cyprogenes because she was born in billowy Cyprus, [200] and Philommedes3 because she sprang from the members.

- 820 ff.

- But when Zeus had driven the Titans from heaven, huge Earth bore her youngest child Typhoeus of the love of Tartarus, by the aid of golden Aphrodite. Strength was with his hands in all that he did and the feet of the strong god were untiring. From his shoulders [825] grew a hundred heads of a snake, a fearful dragon, with dark, flickering tongues, and from under the brows of his eyes in his marvellous heads flashed fire, and fire burned from his heads as he glared.

- 853 ff.

- But when Zeus had conquered him and lashed him with strokes, Typhoeus was hurled down, a maimed wreck, so that the huge earth groaned. And flame shot forth from the thunderstricken lord [860] in the dim rugged glens of the mount,1 when he was smitten. A great part of huge earth was scorched by the terrible vapor and melted as tin melts when heated by men's art in channelled2 crucibles; or as iron, which is hardest of all things, is shortened [865] by glowing fire in mountain glens and melts in the divine earth through the strength of Hephaestus.3 Even so, then, the earth melted in the glow of the blazing fire. And in the bitterness of his anger Zeus cast him into wide Tartarus.

- 1 According to Homer Typhoeus was overwhelmed by Zeus amongst the Arimi in Cilicia. Pindar represents him buried under Aetna, and Tzetzes read Aetna in this passage.

- 954–955

- Happy he! For [Heracles] has finished his great work [955] and lives amongst the undying gods, untroubled and unaging all his days.

- [Most, p. 79:] happy he, for having finished his great work among the immortals he dwells unharmed and ageless for all his days.

fl. 7th c. BC Alcman[edit]

fr. 1 PMGF (Poetarum melicorum Graecorum fragmenta)

- Lines 30-36 [The complete text can be viewed from my laptop]

- ] of whom one with the arrow

- ] with marble millstone

- ] in Hades

- ] they

- ] things never to be forgotten

- they suffered for the evils they plotted.

- There is such a thing as retribution from the gods.

fl. 550-500 BC Ibycus[edit]

S192a (SLG) P.Oxy.2735 fr. 27a [See Wilkinson pp. 141–142]

Classical (c. 500 - 323 BC)[edit]

c. 522 - 443 BC Pindar[edit]

Isthmian 6.31–35

- He took Pergamos, and with Telamon's help he slew the tribes of Meropes, and the herdsman Alcyoneus, huge as a mountain, whom he found at Phlegrae, and he did not keep his hands off the deep-voiced bow-string, not [35] Heracles.

Nemean 1.67–72

- For he [Teiresias] said that when the gods meet the giants in battle on the plain of Phlegra, the shining hair of the giants will be stained with dirt beneath the rushing arrows of that hero [Heracles]. But he himself [70] will have allotted to him in peace, as an extraordinary reward for his great hardship, continuous peace for all time among the homes of the blessed. He will receive flourishing Hebe as his bride and celebrate the wedding-feast, and in the presence of Zeus the son of Cronus he will praise the sacred law.

Nemean 4.24–30

- Heracles, [25] with whom once powerful Telamon destroyed Troy and the Meropes and the great and terrible warrior Alcyoneus, but not before that giant had laid low, by hurling a rock, twelve chariots and twice twelve horse-taming heroes who were riding in them. [30]

Nemean 7.90

- Heracles, you who subdued the Giants,

Olympian 4.6–7

- Son of Cronus, you who hold Aetna, the wind-swept weight on terrible hundred-headed Typhon,

Pythian 1.15–29

- among them is he who lies in dread Tartarus, that enemy of the gods, Typhon with his hundred heads. Once the famous Cilician cave nurtured him, but now the sea-girt cliffs above Cumae, and Sicily too, lie heavy on his shaggy chest. And the pillar of the sky holds him down, [20] snow-covered Aetna, year-round nurse of bitter frost, from whose inmost caves belch forth the purest streams of unapproachable fire. In the daytime her rivers roll out a fiery flood of smoke, while in the darkness of night the crimson flame hurls rocks down to the deep plain of the sea with a crashing roar. [25] That monster shoots up the most terrible jets of fire; it is a marvellous wonder to see, and a marvel even to hear about when men are present. Such a creature is bound beneath the dark and leafy heights of Aetna and beneath the plain, and his bed scratches and goads the whole length of his back stretched out against it.

Pythian 8.12–18

- Porphyrion did not know your power, when he provoked you [Hesychia, "the goddess of domestic tranquillity": Gildersleeve, Pythian 8] beyond all measure. Gain is most welcome, when one takes it from the home of a willing giver. [15] Violence trips up even a man of great pride, in time. Cilician Typhon with his hundred heads did not escape you, nor indeed did the king of the Giants.1 One was subdued by the thunderbolt, the other by the bow of Apollo,

- 1 Porphyrion, mentioned above.

c. 525 - 455 BC Aeschylus[edit]

- she sailed the sea before the breath of earth-born [γίγαντος] Zephyrus.

- or whether, like a bold marshal, she [Athena] is surveying the Phlegraean2 plain, [295]

- 2 The scene of the battle of the Gods and Giants, in which Athena slew Enceladus.

- Pity moved me, too, at the sight of the earth-born dweller of the Cilician caves curbed by violence, that destructive monster [355] of a hundred heads, impetuous Typhon. He withstood all the gods, hissing out terror with horrid jaws, while from his eyes lightened a hideous glare, as though he would storm by force the sovereignty of Zeus. [360] But the unsleeping bolt of Zeus came upon him, the swooping lightning brand with breath of flame, which struck him, frightened, from his loud-mouthed boasts; then, stricken to the very heart, he was burnt to ashes and his strength blasted from him by the lightning bolt. [365] And now, a helpless and a sprawling bulk, he lies hard by the narrows of the sea, pressed down beneath the roots of Aetna; while on the topmost summit Hephaestus sits and hammers the molten ore. There, one day, shall burst forth [370] rivers of fire,1with savage jaws devouring the level fields of Sicily, land of fair fruit—such boiling rage shall Typho, although charred by the blazing lightning of Zeus, send spouting forth with hot jets of appalling, fire-breathing surge.

- Yes, may the gods so grant success to this man. Capaneus is stationed at the Electran gates, another giant of a man, greater than the one described before. [425] But his boast is too proud for a mere human, and he makes terrifying threats against our battlements—which, I hope, chance will not fulfil! For he says he will utterly destroy the city with god's will or without it, and that not even conflict with Zeus, though it should fall before him in the plain, will stand in his way. [430] The god's lightning and thunderbolts he compares to midday heat. For his shield's symbol he has a man without armor bearing fire, and the torch, his weapon, blazes in his hands; and in golden letters he says “I will burn the city.” [435] Against such a man make your dispatch—who will meet him in combat, who will stand firm without trembling before his boasts?

fl. 5th century BC Bacchylides[edit]

15.50 ff. (See also Castriota, pp. 233–234)

- “Battle-loving Trojans: Zeus, the ruler on high who sees all, is not to blame for the great woes of mortals; all men have a chance to reach unswerving Justice, the attendant of holy [55] Eunomia and prudent Themis. Prosperous are they whose children take Justice to live with them. But shameless Hybris, flourishing with shifty greed and lawless empty-headedness, who will swiftly bestow on a man someone else's wealth and power, [60] and then send him into deep ruin—Hybris [Ὕβρις] destroyed the arrogant [ὑπερφίαλος] sons of the Earth, the Giants.”

c. 497 - 406 BC Sophocles[edit]

- Heracles

- And yet, no spearman on the battlefield,

- no earth-born troop of Giants, no wild beast,

- nor Greece, nor any foreign land which I

- purged in my wanderings, could do this to me!

- A woman - weak, not masculine by nature -

- alone, without a sword, has vanquished me!

c. 484 - 425 BC Herodotus[edit]

- This country is called Sithonia. The fleet held a straight course from the headland of Ampelus to the Canastraean headland, where Pallene runs farthest out to sea, and received ships and men from the towns of what is now Pallene but was formerly called Phlegra, namely, Potidaea, Aphytis, Neapolis, Aege, Therambus, Scione, Mende, and Sane.

c. 480 - 406 BC Euripides[edit]

- What rage, what rage does the earth-born race show, and Pentheus, [540] once descended from a serpent—Pentheus, whom earth-born Echion bore, a fierce monster, not a mortal man, but like a bloody giant, hostile to the gods.

- Silenus: O Bromius, labors numberless have I had because of you, now and when I was young and able-bodied! First, when Hera drove you mad and you went off leaving behind your nurses, the mountain-nymphs; [5] next, when in the battle with the Earthborn Giants I took my stand protecting your right flank with my shield and, striking Enceladus with my spear in the center of his targe, killed him. (Come, let me see, did I see this in a dream? No, by Zeus, for I also displayed the spoils to Dionysus.)

- 466–474

- Or in the city of Pallas, the home of Athena of the lovely chariot, shall I then upon her saffron robe yoke horses, [470] embroidering them on my web in brilliant varied shades, or the race of Titans, put to sleep by Zeus the son of Cronos with bolt of flashing flame?

- 177–180

- I appeal then to the thunder of Zeus, and the chariot in which he rode, when he [Herakles, see Gantz p. 448] pierced the Giants, earth's brood, to the heart with his winged shafts, [180] and with gods uplifted the glorious triumph song;

- 906–908

- Oh, oh! what are you doing, Pallas, child of Zeus, to the house? You are sending hell's confusion against the halls, as once you did on Enceladus.

- 1192–1194

- My son [Heracles], my own enduring son, that marched with gods to Phlegra's plain, there to battle with giants and slay them, warrior that he was.

- 1271–1273

- Heracles

- what did I not destroy, whether lions, or triple-bodied Typhons, or giants or the battle against the hosts of four-legged Centaurs?

- 205–218

- I am glancing around everywhere. See the battle of the giants, on the stone walls.

- I am looking at it, my friends.

- Do you see the one [210] brandishing her gorgon shield against Enceladus? 565

- I see Pallas, my own goddess.

- Now what? the mighty thunderbolt, blazing at both ends, in the far-shooting hands of Zeus?

- I see it; [215] he is burning the furious Mimas to ashes in the fire.

- And Bacchus, the roarer, is killing another of the sons of Earth with his ivy staff, unfit for war.

- 987–997

- Creusa

- Listen, then; you know the battle of the giants?

- Tutor

- Yes, the battle the giants fought against the gods in Phlegra.

- Creusa

- There the earth brought forth the Gorgon, a dreadful monster.

- Tutor

- [990] As an ally for her children and trouble for the gods?

- Creusa

- Yes; and Pallas, the daughter of Zeus, killed it.

- Tutor

- [What fierce shape did it have?

- Creusa

- A breastplate armed with coils of a viper.]

- Tutor

- Is this the story which I have heard before?

- Creusa

- [995] That Athena wore the hide on her breast.

- Tutor

- And they call it the aegis, Pallas' armor?

- Creusa

- It has this name from when she darted to the gods' battle.

- 1528–1529

- Creusa

- By Athena Nike, who once raised her shield against the giants, in her chariot beside Zeus,

- 222–224

- embroidering with my shuttle, in the singing loom, the likeness of Athenian Pallas and the Titans;

- 127–130

- Ah, ah! How proud, how fearful to see, like an earth-born giant, with stars engraved on his shield, not resembling [130] mortal race.

- 1129–1133

- At Electra's gate Capaneus brought up his company, bold as Ares for the battle; [1130] this device his shield bore upon its iron back: an earth-born giant carrying on his shoulders a whole city which he had wrenched from its base, a hint to us of the fate in store for Thebes.

c. 446 - 386 BC Aristophanes[edit]

- 553

- Oh, Cebriones! oh, Porphyrion! what a terribly strong place!

- 823–831

- Pisthetaerus

- No, it's rather the plain of Phlegra, where the gods [825] withered the pride of the sons of the Earth with their shafts.

- Leader of the Chorus

- Oh! what a splendid city! But what god shall be its patron? for whom shall we weave the peplus?

- Euelpides

- Why not choose Athena Polias?

- Pisthetaerus

- Oh! what a well-ordered town it would be [830] to have a female deity armed from head to foot, while Clisthenes was spinning!

- 1249–1252

- I shall send more than six hundred porphyrions [1250] clothed in leopards' skins up to heaven against him [Zeus]; and formerly a single Porphyrion gave him enough to do.

- 565

- Let us sing the glory of our forefathers; ever victors, both on land and sea, they merit that Athens, rendered famous by these, her worthy sons, should write their deeds upon the sacred peplus.

c. 425 - 348 BC Plato[edit]

- [6b] ... And so you believe that there was really war between the gods, and fearful enmities and battles and other things of the sort, such as are told of by the poets and represented in varied designs [6c] by the great artists in our sacred places and especially on the robe which is carried up to the Acropolis at the great Panathenaea? for this is covered with such representations. Shall we agree that these things are true, Euthyphro?

- [378c] if we wish our future guardians to deem nothing more shameful than lightly to fall out with one another; still less must we make battles of gods and giants the subject for them of stories and embroideries,1 and other enmities many and manifold of gods and heroes toward their kith and kin.

- 1 On the Panathenaic πέπλος of Athena.

- Stranger: And indeed there seems to be a battle like that of the gods and the giants going on among them, because of their disagreement about existence.

- Theaetetus: How so?

- Stranger: Some of them1 drag down everything from heaven and the invisible to earth, actually grasping rocks and trees with their hands; for they lay their hands on all such things and maintain stoutly that that alone exists which can be touched and handled; [246b] for they define existence and body, or matter, as identical, and if anyone says that anything else, which has no body, exists, they despise him utterly, and will not listen to any other theory than their own.

- Theaetetus: Terrible men they are of whom you speak. I myself have met with many of them.

- Stranger: Therefore those who contend against them defend themselves very cautiously with weapons derived from the invisible world above, maintaining forcibly that real existence consists of certain ideas which are only conceived by the mind and have no body. But the bodies of their opponents, and that which is called by them truth, they break up into small fragments [246c] in their arguments, calling them, not existence, but a kind of generation combined with motion. There is always, Theaetetus, a tremendous battle being fought about these questions between the two parties.

- 1 The atomists (Leucippus, Democritus, and their followers), who taught that nothing exists except atoms and the void. Possibly there is a covert reference to Aristippus who was, like Plato, a pupil of Socrates.

- 190b

- [190b] swiftly round and round. The number and features of these three sexes were owing to the fact that the male was originally the offspring of the sun, and the female of the earth; while that which partook of both sexes was born of the moon, for the moon also partakes of both.1 They were globular in their shape as in their progress, since they took after their parents. Now, they were of surprising strength and vigor, and so lofty in their notions that they even conspired against the gods; and the same story is told of them as Homer relates of

- 190c

- [190c] Ephialtes and Otus1 that scheming to assault the gods in fight they essayed to mount high heaven.

- “Thereat Zeus and the other gods debated what they should do, and were perplexed: for they felt they could not slay them like the Giants, whom they had abolished root and branch with strokes of thunder—it would be only abolishing the honors and observances they had from men; nor yet could they endure such sinful rioting. Then Zeus, putting all his wits together, spoke at length and said: ‘Methinks I can contrive that men, without ceasing to exist, shall give over their iniquity through a lessening of their strength.

- 1 Hom. Od. 11.305ff.; Hom. Il. 5.385ff.

384 - 322 BC Aristotle[edit]

- Whenever an earthquake of this kind … as we see from Sipylus and the Phlegraean plain and the district in Liguria, which were devastated by this kind of earthquake.

On Marvellous Things Heard 838a 27

- Near the promontory of Iapygia is a spot, in which it is alleged, so runs the legend, that the battle between Heracles and the giants took place; from here flows such a stream of ichor that the sea cannot be navigated at the spot owing to the heaviness of the scent. They say that in many parts of Italy there are many memorials of Heracles on the roads over which he travelled. But about Pandosia in Iapygia footprints of the god are shown, upon which no one may walk.

c. 350 BC – 323 BC? Batrachomyomachia[edit]

- the Giants, those earth-born [γηγενἑων] men.

- So said son of Cronus; but Hera answered him: "Son of Cronos, neither the might of Athena nor of Ares can avail to deliver the Frogs from utter destruction. Rather, come and let us all go to help them, or else let loose your weapon, the great and formidable Titan-killer with which you killed Capaneus, that doughty man, and great Enceladus and the wild tribes of Giants;

Hellenistic (323 - 146 BC)[edit]

c. 305 – 240 BC Callimachus[edit]

fragment 117 (382) (pp. 342–343)

- The three-forked islanda (that lies) upon deadly Enceladus.

- Schol. Pind. : Pindar says that Aetna lies upon Typhon, Callimachus says upon Enceladus

- a Sicily, under which is buried the giant Enceladus

Hymn 4 (to Delos)

- 141–146 (pp. 96–97)

- And even as when the mount of Aetna smoulders with fire and all its secret depths are shaken as the giant under earth, even Briares, shifts to his other shoulder,a and with the tongs of Hephaestus roar furnaces and handiwork withal;

- a Cf. Frazer, G.B. [Golden Bough]3, Adonis, Attis, Osiris, i. p. 197: "The people of Timor, in the East Indies, think that the earth rests on the shoulders of a mighty giant, and that when he is weary of bearing it on one shoulder he shifts it to the other and so causes the ground to quake." Ibid. p. 200: "The Tongans think that the earth is supported on the prostrate form of the god Móooi. When he is tired of lying in one posture, he tries to turn himself about, and that causes an earthquake."

- And even as when the mount of Aetna smoulders with fire and all its secret depths are shaken as the giant under earth, even Briares, shifts to his other shoulder,a and with the tongs of Hephaestus roar furnaces and handiwork withal;

- 173 ff. (pp. 98–99)

- When Titans of a later day shall rouse up against the Hellenes barbarian sword and Celtic war,e

- e From 300 B.C. there was a great southward movement of Celts from the Balkan peninsula. In 280/279 they invaded Greece, where they attacked Delphi, but were miraculously routed by Apollo. It was shortly after this that a body of them settled in the district of Asia afterwards known as Galatia (circ. 240 B.C.).

- [Here conflating the Titans with the Giants (see Vian and Moore 1988 p. 193; Mineur p. 170)

- When Titans of a later day shall rouse up against the Hellenes barbarian sword and Celtic war,e

Hymn 5 (on the Bath of Pallas) 5–12

- Never did Athena wash her mighty arms before she drave the dust from the flanks of her horses—not even when she returned from the battle of the lawless Giants; but far first she loosed from the car her horses' necks, and in the springs of Oceanus washed the flecks of sweat and from their mouths that champed the bit cleansed the clotted foam.

Hymn 6 (to Demeter) 25 ff. (pp. 126 ff.)

- then the worse counsel took hold of Erysichthon. He hastened with twenty attendants, all in their prime, all men-giants able to lift a whole city, arming them both with double axes and hatchets, and they rushed shameless into the grove of Demeter.

fl. c. 300 - 250 BC Apollonius of Rhodes[edit]

- 3.232–234 (pp. 210–211)

- [Hephaestus] forged a plough of unbending adament, all in one piece, in payment of thanks to Helios, who had taken the god up in his chariot when faint from the Phlegraean fight.

- 3.1225–7 (pp. 276–277)

- Then Aeetes arrayed his breast in the stiff corset which Ares gave him when he had slain Phlegraean Mimas with his own hands;

fl. c. 285 - 247 BC Lycophron[edit]

Alexandra

- 63 ff. (pp. 498–499)

- [Paris] wounded by the giant-slaying arrows of his adversary [Philoctetes]

- 115, 127 (pp. 504–505)

- [115] husband,a whose spouse is Torone of Phlegra,

- [127] he came as a wanderer to Pallenia, nurse of the earth-born

- a Proteus came from his home in Egypt to Pallene (=Phlegra, Herod. viii. 123 in Chacide), the birth-place of the giants, where he married Torone,

- 688–693 (pp. 550–551)

- Thereafter the islandm that crushed the back of the Giants and the fierce form of Typhon, shall receive him journeying alone: an island boiling with flame, wherein the king of the immortals established an ugly race of apes, in mockery of all who raised war against the sons of Cronus.

- m Pithecussa=Aenaria, under which the giant Typhoeus lies buried and where the Cercopes were turned into apes by Zeus to mock the giants (Ovid, M. xiv. 90).

- Thereafter the islandm that crushed the back of the Giants and the fierce form of Typhon, shall receive him journeying alone: an island boiling with flame, wherein the king of the immortals established an ugly race of apes, in mockery of all who raised war against the sons of Cronus.

- 706–709 (pp. 552–553)

- Stream of black Styx, where Temieus [Zeus] made the seat of oath-swearing [see Illiad 15.37] for the immortals, drawing the water in golden basins for libation, when he was about to go against the Giants and Titans

- 1356–1358 (pp. 606–607)

- and themh who drew the root of their race from the blood of the Sithoniani giants.

- h The Pelasgians

- i Sithonia and Pallene, the middle and southern spurs of Chalcidice, are the home of the giants; cf. 1406 f.

- and themh who drew the root of their race from the blood of the Sithoniani giants.

- 1404–1408 (pp. 610–611)

- By him all the lands of Phlegra shall be enslaved and the ridge of Thrambus and spur of Titon by the sea and the plains of the Sithonians and the fields of Pallene, which the ox-horned Brychon,r who served the giants, fattens with his waters.

- r River in Pallene (Hesych.).

- By him all the lands of Phlegra shall be enslaved and the ridge of Thrambus and spur of Titon by the sea and the plains of the Sithonians and the fields of Pallene, which the ox-horned Brychon,r who served the giants, fattens with his waters.

c. 270 - 201 BC Naevius[edit]

Bellum Punicum [The Punic War] fragment

- Warmington

- p. 66

- Priscianus, ap. G.L., II, 198, 6: (p.30) Naevius in carmine Belli Punici I—

- p. 66

- Inerant signa expressa quo modo Titani

- bicorpores Gigantes magnique Atlantes

- Runcus atque Porporeus filii Terras.

- Cp. Prisc., G.L., 217,12.

- p. 67

- From Book I ? Aeneas' ship,a built by Mercury?:

- Priscianus on the genitve singular in '-as.' ... Naevius in The Song of the Punic War, book I (?)—

- On it were modeled images in the fashion of Titans and two-bodied Giants and mighty Atlases, and Runcus too and the Crimson-hued, sons of Earth.

- p. 67

- Henry T. Rowell, "The Original Form of Naevius' Bellum Punicum", The American Journal of Philology Vol. 68, No. 1 (1947), pp. 21-46. (JSTOR 291058)

- p. 34

- Fortunately three lines of Bellum Punicum (frg. 19) preserved by Priscian (I, p. 198 Hertz) and assigned expressly to Book I furnish the means oe approach. They read as follows:

- Inerant signa expressa / quomodo Titani

- bicorpores Gigantes / magnique Atlantes

- Runcus ac Purpureus / filii Terras

- Fortunately three lines of Bellum Punicum (frg. 19) preserved by Priscian (I, p. 198 Hertz) and assigned expressly to Book I furnish the means oe approach. They read as follows:

- p. 34

- Translation by Marco Petrolino

- [5] There were engraved images [depicting] in what the way the Titans, the two-bodied Giants, and great Atlantis, Rucus and Purpureus, children of Ge...

- Vian and Moore 1988, p. 193:

- They [Giants] are πολυσώματοι (Diod. 1, 26) or bicorpores (Naevius Bell. Pun. frg. Strzelecki 4), that is to say anguipèdes.

b. c. 275 BC Euphorion[edit]

Fragment 169 (Lightfoot = Powell 166? see Lightfoot, pp. 394–395)

- 169 Scholiast on Dionysius the Periegete

- These pillars were initially called the pillars of Cronos, because the boundary of his kingdom lay in these regions; next they were to belong to Briareus, as Euphorion says; and thirdly they became known as the pillars of Heracles.

- cf. Scholiast on Pindar, Nemean Odes

- The pillars of Heracles are also known as the pillars of Briareus, according to <Euphorion??>:

- And the pillars of Aegaeon, the Giant, lord of the sea.194

- 194 See Parthenius 34.

- And the pillars of Aegaeon, the Giant, lord of the sea.194

2nd c. BC Nicander[edit]

Europia fragment 26 (see Gow and Scholfield pp. 140–141, [22])

- Athos: a mountain in Thrace, so named after the giant [gigantos] Athos as Nicander in the fifth book of his Europia says:

And one beholding Thracian Athos towering up beneath the stars, heard his voice as he shouted beneath the fathomless lake. So with his voice he hurled two missiles wrenched erewhile from the steep promontory of Canastrum.

late 2nd c. BC Antipater of Sidon[edit]

Paton, pp. 396–397:

- 748._ANTIPATER OF SIDON

- What one-eyed Cyclops built all this vast stone

- mound of Assyrian Semiramis, or what giants, sons

- of earth, raised it to reach near to the seven Pleiads,

- inflexible, unshakable, a mass weighing on the broad

- earth like to the peak of Athos ? Ever blessed

- people, who to the citizens of Heraclea . . .

Gow, p. 24 XXXV 424–427: [Greek containing Ossa and Pelion] [Cited by Vian and Moore 1988, p. 193: "They pile up mountains to climb the sky and merge more or less with Aloades (-»Aloadai) ... Antipater Sidonius, Gow / Page, Hell. Epigr. v. 410-417. 424-427".]

Roman (146 - 1 BC)[edit]

fl. c. 72 BC. Parthenius[edit]

Fragment 34 (Lightfoot) Lightfoot, p. 525

- 34 Scholiast on Dionysius the Periegete

- ... Cádiz, and that is where the pillars of Heracles are. Dionysus' are in the east. Parthenius says the pillars belong to Briareus:

- To bear us witness, at Cádiz he left a record (?),

- Erasing the old name of ancient Briareus.27

- 27 One of the hundred-handers or hekatogcheirs who supported Zeus against the Titans in Hesiod's Theogony. For his connection with the Pillars of Heracles, see Aristotle fr. 678 Rose, Plut. Mor. 420 A, and Euphorion 169.

106 - 43 BC Cicero[edit]

De natura deorum 3.59

- The fifth [Minerva] is Pallas, who is said to have slain her father when he attempted to violate her maidenhood; she is represented with wings attached to her ankles.

- Wherefore, if you are accustomed to marvel at my wisdom—and would that it were worthy of your estimate and of my cognomen1 —I am wise because I follow Nature as the best of guides and obey her as a god; and since she has fitly planned the other acts of life's drama, it is not likely that she has [p. 15] neglected the final act as if she were a careless playwright. And yet there had to be something final, and—as in the case of orchard fruits and crops of grain in the process of ripening which comes with time—something shrivelled, as it were, and prone to fall. But this state the wise man should endure with resignation. For what is warring against the gods, as the giants did, other than fighting against Nature?

c. 99 - 55 BC Lucretius[edit]

- 1.62–79

- Whilst human kind

- Throughout the lands lay miserably crushed

- Before all eyes beneath Religion- who

- Would show her head along the region skies,

- Glowering on mortals with her hideous face-

- A Greek it was who first opposing dared

- Raise mortal eyes that terror to withstand,

- Whom nor the fame of Gods nor lightning's stroke

- Nor threatening thunder of the ominous sky

- Abashed; but rather chafed to angry zest

- His dauntless heart to be the first to rend

- The crossbars at the gates of Nature old.

- And thus his will and hardy wisdom won;

- And forward thus he fared afar, beyond

- The flaming ramparts of the world, until

- He wandered the unmeasurable All.

- Whence he to us, a conqueror, reports

- What things can rise to being, what cannot,

- And by what law to each its scope prescribed,

- Its boundary stone that clings so deep in Time.

- Wherefore Religion now is under foot,

- And us his victory now exalts to heaven.

- 4.134–137

- As we behold the clouds grow thick on high

- And smirch the serene vision of the world,

- Stroking the air with motions. For oft are seen

- The giants' faces flying far along

- And trailing a spread of shadow;

- 5.110–125

- But ere on this I take a step to utter

- Oracles holier and soundlier based

- Than ever the Pythian pronounced for men

- From out the tripod and the Delphian laurel,

- I will unfold for thee with learned words

- Many a consolation, lest perchance,

- Still bridled by religion, thou suppose

- Lands, sun, and sky, sea, constellations, moon,

- Must dure forever, as of frame divine-

- And so conclude that it is just that those,

- (After the manner of the Giants), should all

- Pay the huge penalties for monstrous crime,

- Who by their reasonings do overshake

- The ramparts of the universe and wish

- There to put out the splendid sun of heaven,

- Branding with mortal talk immortal things-

- Though these same things are even so far removed

- From any touch of deity and seem

- So far unworthy of numbering with the gods,

- That well they may be thought to furnish rather

- A goodly instance of the sort of things

- That lack the living motion, living sense.

fl. c. 60 - 30 BC Diodorus Siculus[edit]

- Furthermore, the Egyptians relate in their myths that in the time of Isis there were certain creatures of many bodies, who are called by the Greeks Giants,54 but by themselves . . ., these being the men who are represented on their temples in monstrous form and as being cudgelled by Osiris. [7] Now some say that they were born of the earth at the time when the genesis of living things from the earth was still recent, while some hold that they were only men of unusual physical strength who achieved many deeds and for this reason were described in the myths as of many bodies. [8] But it is generally agreed that when they stirred up war against Zeus and Osiris they were all destroyed.

- 54 But the Giants of Greek mythology were represented with "huge," not "many," bodies.