User:Pickersgill-Cunliffe/sandbox2

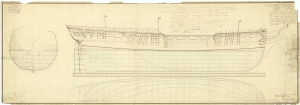

Design of HMS Artois, name ship of Diamond's class

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | HMS Diamond |

| Ordered | 28 March 1793 |

| Cost | £22,168[1] |

| Laid down | April 1793 |

| Launched | 17 March 1794 |

| Commissioned | April 1794 |

| Fate | Broken up June 1812 |

| General characteristics [1] | |

| Class and type | Artois-class fifth-rate frigate |

| Tons burthen | 99559⁄94 (bm) |

| Length |

|

| Beam | 39 ft 3 in (12 m) |

| Draught |

|

| Depth of hold | 13 ft 9 in (4.2 m) |

| Propulsion | Sails |

| Complement | 270 (later 315) |

| Armament |

|

HMS Diamond was a 38-gun fifth-rate Artois-class frigate of the Royal Navy.

Construction

[edit]Diamond was a 38-gun, 18-pounder, fifth-rate Artois-class frigate designed by Sir John Henslow.[2] She and her class were ordered soon after the start of the French Revolutionary War to provide an influx of modern warships for the Royal Navy.[3] Diamond was the fourth ship of her class; of the nine ships of the class seven, including Diamond, were built of oak while the final two were built of fir.[3] The Artois-class frigates were an improvement on the 18-pounder frigates of the American Revolutionary War which were found to be too small and that their battery placement made them unstable at sea.[2] To counter this, Diamond and her contemporaries built in the 1790s were lengthened forwards to make them faster and more stable.[2] The extra space provided by this expansion made the ships faster but did not stop the issue of violent pitching, which would not be fixed until HMS Active was launched as an improvement to the class in 1799.[4] Despite this, the class would go on to gain a reputation as 'crack frigates'.[5] They were perfect for their assigned role as frigates on blockade duties, being large enough to fight any French frigate sent to attack them while on station but also fast enough and weatherly enough to be able to stay at their posts no matter the weather type.[6]

Diamond was ordered on 28 March 1793 to be built at Deptford by William Barnard.[1] She was laid down in April and launched on 17 March 1794 with the following dimensions: 146 feet (44.5 m) along the gun deck, 121 feet 6 inches (37 m) at the keel, with a beam of 39 feet 3 inches (12 m) and a depth in the hold of 13 feet 9 inches (4.2 m). She measured 99559⁄94 tons burthen.[1] The fitting out process for Diamond was completed at Deptford on 9 June.[1] On 19 November eight 32-pound carronades were added to the Artois-class ships by Admiralty Order, leading some to describe them as 44-gun frigates in the future.[7] No further changes to the armament of Diamond are recorded, but on 26 March 1796 she was supplied with shells sized for 24-pound guns, suggesting that for at least some of her service she carried guns of this calibre.[8] On 20 June another Admiralty Order saw the ship's crew complement increase from 270 to 284.[7] At a later point in her service this was again increased, this time to 315.[1]

Service

[edit]1794-1795

[edit]

Diamond was commissioned in April 1794 with Captain Sidney Smith as her first commanding officer.[1] She was then ordered to form part of Commodore John Borlase Warren's Western Squadron in the English Channel, based mostly around Audierne Bay.[1] On 23 August Diamond and the squadron destroyed the French 36-gun frigate La Volontaire on the Penmarks and then chased and destroyed the 12-gun L'Alerte in the nearby Audierne Bay.[9]

On 4 January 1795 Diamond completed a daring reconnaissance of the French harbour of Brest.[10] The British government had received word that the fleet of Louis Thomas Villaret de Joyeuse had possibly sailed on a cruise and Warren selected Diamond for the role of investigating the harbour itself for signs of the French fleet.[11] Having disguised her as a French ship on 3 January, the next day Smith sailed Diamond into Brest roads behind the French ship-of-the-line Caton and, navigating by moonlight, managed to pass Caton and two other French warships.[12] By the morning of 5 January the rest of the roads were visible to Diamond and having ascertained that there were no more French warships anchored there she turned to leave, still undetected.[12] As Diamond again passed Caton, which was at the time jury rigged, a French corvette raised the alarm about her true identity.[12] Captain Smith moved Diamond closer to Caton and spoke to her captain in French, convincing him that Diamond was actually a frigate of the French Norway Squadron and having him call off the other French ships that were readying to close on Diamond.[12] Successfully avoiding further discovery, Diamond was able to freely sail from the area.[12]

By May she was serving in the squadron of Captain Sir Richard Strachan and on 9 May she participated in the capture of a French convoy of transports in Carperet Bay.[10][11] The squadron had been at anchor in Jersey's Gourville Bay when the convoy of thirteen ships was spotted running close along the coastline; the squadron weighed anchor and chased the convoy which looked for safety under the gunline of a small battery of guns, however the squadron's gunnery quickly destroyed the battery.[13] Twelve of the ships were abandoned by their crews at this point and easily captured, while the thirteenth escaped by going around Cape Carteret. The twelve ships captured were ten transports carrying naval stores and their escorting brig and lugger.[13] Under the command of Smith the frigate continued to make bold attacks on the French, including an ineffectual attempt to attack two French ships that were guarding a number of merchantmen under cover of the guns of the La Hogue batteries, on 4 July.[11] This resulted in one man of Diamond being killed and two more injured.[11] In the same month Smith sent the ship's boats in to the island of St Marcou off the coast of Normandy which they then used to communicate from with French royalists.[11] Diamond continued actively on the coast of France through the year, driving ashore the French 14-gun L'Assemblee Nationale on 2 September.[Note 1][10] The French ship had attempted to escape the pursuit of Diamond by weaving through the rocks on the coast of Treguier but wrecked herself on one of them in attempting such, and while Smith sent his ship's boats to assist in rescuing the crew twenty Frenchmen were killed and the ship quickly destroyed by the rough seas.[14]

1796

[edit]On 17 March 1796 a French convoy consisting of the 16-gun corvette L'Etourdie, three luggers, four brigs, and two sloops was chased in to Erqui by the Jersey-based forces of Captain Philippe d'Auvergne.[12] Seeing this, Diamond looked to make an attack on the sheltering convoy and was joined for the purpose by the cutter HMS Liberty and the hired lugger Aristocrat.[10] Diamond led the ships in and destroyed a gun that had been set up to protect the entrance to Erqui, but a gun battery situated on higher ground could not be destroyed by the ships.[12] Boats with seamen and marines from Diamond were sent in to silence the battery so that further progress could be made and the French countered this by deploying soldiers to protect the entrance of the battery.[12] To avoid a frontal assault on the battery Lieutenant Pine of Diamond had his men climb the precipice at the front of the battery, thus avoiding the soldiers and quickly taking the guns with this unexpected attack.[12] With the battery no longer attacking the British, Liberty and Aristocrat began to attack the convoy which in turn beached itself in an attempt to avoid destruction.[12] Smith observed that the crew of L'Etourdie had abandoned her and ordered boarding parties in; heavy enemy fire meant that little could be done to capture other vessels of the convoy and L'Etourdie and one of the brigs were burned.[12][10] Later on Diamond's boats came in to shore again and under the cover of Aristocrat's guns burned the rest of the convoy where it lay.[12] Pine was badly wounded in the attack and the leader of the marines, Lieutenant Carter, died of his wounds and two more seamen were killed.[14]

On 17 April Diamond attempted to cut out the French privateer La Vengeur at Le Havre; Smith brought a number of boats into the harbour that evening and together they captured a lugger, however the setting tide then forced them further up the Seine from where they were unable to escape for the entire night.[10][14]. In the early morning the crews began to use their boats to tow the captured lugger back towards the sea but in doing so they were spotted and attacked by a series of French gun boats and a larger lugger.[15] A fight between the two luggers ensued and after four of Smith's men were killed and another seven wounded, he was forced to surrender.[16] With Smith gone Diamond continued to serve off St Marcou, now an official Royal Navy station.[17] Captain Thomas Le Marchant Gosselin was appointed as a temporary replacement for Smith on 22 April and in the same month Diamond took the French 10-gun privateer Le Pichegru off Cherbourg, while in company with the sloop HMS Rattler.[10][17] Gosselin left Diamond on 25 July and was replaced in December by Captain Sir Richard Strachan, under whose control Diamond had been in 1795.[10][12][17] She ended the year successfully, taking the French privateers L'Esperance, a brig, on 24 December and the 14-gun L'Amaranthe, a corvette, on 31 December, both off Alderney.[10][18]

1797-1800

[edit]In 1797 Diamond continued to serve in the same area of the Channel, taking the privateer cutter L'Esperance off Le Havre on 27 April.[10] In the same location she destroyed a privateer lugger on 23 September.[10] Strachan left Diamond in February 1799 to take command of the ship of the line HMS Captain.[19]

Captain Edward Griffith took command of Diamond in April 1799 and she continued her Channel activities, participating in operations at Quiberon in June before escorting a convoy to the Cape of Good Hope in July.[10] Having returned shortly afterwards the frigate resumed her activities assisting land operations with the unsuccessful Ferrol Expedition in August 1800.[20] In this period the frigate was again detached in a squadron commanded by Captain Sir Edward Pellew.[20]

1801

[edit]On 20 August 1801 the boats of Diamond and the frigates HMS Fisgard and HMS Boadicea captured the Spanish 20-gun Neptuno at Corunna.[10]

1802-?

[edit]Diamond became the flag ship of Admiral Mark Milbanke, still in the Channel, in 1802, with Captain Thomas Elphinstone assuming command in June of the same year.[10]

She took the Spanish 16-gun Infante Don Carlos on 7 December 1804.[10]

Captain Elphinstone was replaced by Captain George Argles in July 1806 and from the Channel she escorted a convoy to the coast of Africa on 21 May 1807.[10]

Diamond sailed for Jamaica on 23 May 1808.[10]

Fate

[edit]Diamond was paid off and put in ordinary in 1810 and was broken up at Sheerness Dockyard in June 1812.[10]

Prizes

[edit]| Vessels captured or destroyed for which Diamond's crew received full or partial credit | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Ship | Nationality | Type | Fate | Ref. |

Notes and citations

[edit]Notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Winfield (2008), p. 346.

- ^ a b c Winfield (2008), p. 345.

- ^ a b Winfield (2008), p. 344.

- ^ Gardiner (1994), pp. 54–55.

- ^ Wareham (1999), p. 178.

- ^ Gardiner (1994), p. 56.

- ^ a b Gardiner (1994), p. 33.

- ^ Gardiner (1994), p. 102.

- ^ Winfield (2008), pp. 346–347.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Winfield (2008), p. 347.

- ^ a b c d e Marshall (1823c), p. 295.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Phillips, Diamond (38) (1794). Michael Phillips' Ships of the Old Navy. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ a b Marshall (1823d), p. 287.

- ^ a b c d Marshall (1823c), p. 296.

- ^ Marshall (1823c), pp. 296–297.

- ^ Marshall (1823c), p. 297.

- ^ a b c Marshall (1823a), p. 418.

- ^ Marshall (1823d), p. 291.

- ^ Marshall (1823d), pp. 287–288.

- ^ a b Marshall (1823b), p. 557.

References

[edit]- Gardiner, Robert (1994). The Heavy Frigate: Eighteen-Pounder Frigates. Vol. 1. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0 85177 627 2.

- Marshall, John (1823a). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. 1, part 2. London: Longman and company. pp. 671–2, 416–9.

- Marshall, John (1823b). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. 1, part 2. London: Longman and company. pp. 548–59.

- Marshall, John (1823c). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. 1, part 1. London: Longman and company. pp. 291–322.

- Marshall, John (1823d). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. 1, part 1. London: Longman and company. pp. 284–91.

- Winfield, Rif (2008). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. London: Seaforth. ISBN 1-86176-246-1.

Sources not yet implemented

[edit]- Brenton, Edward Pelham (1837). The Naval History of Great Britain, from the year MDCCLXXXIII. to MDCCCXXXVI. Vol. 1. London: Henry Colburn.

- Clowes, William Laird (1899). The Royal Navy: A History from the Earliest Times to 1900. Vol. 4. London: Sampson Low, Marston and Company. ISBN 1861760132.

- Clowes, William Laird (1900). The Royal Navy: A History from the Earliest Times to 1900. Vol. 5. London: Sampson Low, Marston and Company. ISBN 1861760140.

- Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2010). Ships of the Royal Navy. Newbury: Casemate. ISBN 978-1-935149-07-1.

- Duncan, Archibald (1805). The British Trident; or, Register of Naval Actions; including Authentic Accounts of all the most Remarkable Engagements at Sea, in which The British Flag has been Eminently Distinguished; from the period of the memorable Defeat of the Spanish Armada, to the Present Time. Vol. 3. London: James Cundee.

- Henderson, James (1970). The Frigates. London: A. & C. Black. ISBN 1-85326-693-0.

- Hore, Peter (2015). Nelson's Band of Brothers. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978 1 84832 779 5.

- James, William (1837a). The Naval History of Great Britain: A New Edition, with Additions and Notes, and an Account of the Burmese War and the Battle of Navarino. Vol. 1. London: Richard Bentley.

- James, William (1837b). The Naval History of Great Britain: A New Edition, with Additions and Notes, and an Account of the Burmese War and the Battle of Navarino. Vol. 2. London: Richard Bentley.

- James, William (1886). The Naval History of Great Britain: A New Edition, with Additions and Notes, and an Account of the Burmese War and the Battle of Navarino. Vol. 3. London: Richard Bentley & Son.

- Marshall, John (1825). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. 2, part 2. London: Longman and company. p. 719.

- Ralfe, James (1828). The Naval Biography of Great Britain: Consisting of Historical Memoirs of Those Officers of the British Navy who Distinguished Themselves During the Reign of His Majesty George III. Vol. 4. London: Whitmore & Fenn. OCLC 561188819.

- Rodger, N. A. M. (2004). The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain, 1649-1815. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-713-99411-8.

- Schomberg, Isaac (1802). Naval Chronology, Or an Historical Summary of Naval and Maritime Events from the Time of the Romans, to the Treaty of Peace 1802: With an Appendix. Vol. 5. London: T. Egerton.

- Wareham, Thomas Nigel Ralph (1999). The Frigate Captains of the Royal Navy, 1793-1815 (PhD). University of Exeter.

External links

[edit] Media related to HMS Diamond (ship, 1794) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to HMS Diamond (ship, 1794) at Wikimedia Commons- Ships of the Old Navy