User:Pseudo-Richard/Christianity and violence (old)

| This article is of a series on |

| Criticism of religion |

|---|

The article's lead section may need to be rewritten. (November 2010) |

The relationship of Christianity and violence is the subject of controversy because one view is that Christianity advocates peace, love and compassion while it is also viewed as a violent religion.[1][2][3] Peace, compassion and forgiveness of wrongs done by others are key elements of Christian teaching. However, Christians have struggled since the days of the church fathers with the question of when the use of force is justified. Such debates have led to concepts such as just war theory. Throughout history, certain teachings from theOld Testament, the New Testament and Christian theology have been used to justify the use of force against heretics, sinners and external enemies.

Although Christian teaching has been relied on to justify a Christian use of force, another Christian thought is of opposition to the use of force and violence. Sects that have emphasized pacificism as a central tenet of faith have resulted from the latter thought. Christians have also engaged in violence against those that they classify as heretics and non-believers specifically to enforce orthodoxy of their faith. In Letter to a Christian Nation, critic of religion Sam Harris writes that "...faith inspires violence in at least two ways. First, people often kill other human beings because they believe that the creator of the universe wants them to do it... Second, far greater numbers of people fall into conflict with one another because they define their moral community on the basis of their religious affiliation..."[4]

Christian theologians point to a strong doctrinal and historical imperative within Christianity against violence, particularly Jesus' Sermon on the Mount, which taught nonviolence and "love of enemies". For example, Weaver asserts that Jesus' pacifism was "preserved in the justifiable war doctrine that declares all war as sin even when declaring it occasionally a necessary evil, and in the prohibition of fighting by monastics and clergy as well as in a persistent tradition of Christian pacifism."[5]

Definition of violence

[edit]Abhijit Nayak writes that:

The word "violence" can be defined to extend far beyond pain and shedding blood. It carries the meaning of physical force, violent language, fury and, more importantly, forcible interference.[6]

Terence Fretheim writes:

For many people, ... only physical violence truly qualifies as violence. But, certainly, violence is more than killing people, unless one includes all those words and actions that kill people slowly. The effect of limitation to a “killing fields” perspective is the widespread neglect of many other forms of violence. We must insist that violence also refers to that which is psychologically destructive, that which demeans, damages, or depersonalizes others. In view of these considerations, violence may be defined as follows: any action, verbal or nonverbal, oral or written, physical or psychical, active or passive, public or private, individual or institutional/societal, human or divine, in whatever degree of intensity, that abuses, violates, injures, or kills. Some of the most pervasive and most dangerous forms of violence are those that are often hidden from view (against women and children, especially); just beneath the surface in many of our homes, churches, and communities is abuse enough to freeze the blood. Moreover, many forms of systemic violence often slip past our attention because they are so much a part of the infrastructure of life (e.g., racism, sexism, ageism).[7]

Heitman and Hagan identify the Inquisition, Crusades, Wars of Religion and antisemitism as being "among the most notorious examples of Christian violence".[8] To this list, J. Denny Weaver adds, "warrior popes, support for capital punishment, corporal punishment under the guise of 'spare the rod and spoil the child,' justifications of slavery, world-wide colonialism in the name of conversion to Christianity, the systemic violence of women subjected to men." Weaver employs a broader definition of violence that extends the meaning of the word to cover "harm or damage", not just physical violence per se. Thus, under his definition, Christian violence includes "forms of systemic violence such as poverty, racism, and sexism."[5]

Christianity as a violent religion

[edit]Charles Selengut characterizes the phrase "religion and violence" as "jarring", asserting that "religion is thought to be opposed to violence and a force for peace and reconciliation. He acknowledges, however, that "the history and scriptures of the world's religions tell stories of violence and war as they speak of peace and love."[9]

Some critics of religion (in general) such as Christopher Hitchens and Richard Dawkins go farther and argue that religions do tremendous harm to society in three ways:[10][page needed][11][page needed]

- Religions sometimes use war, violence, and terrorism to promote their religious goals

- Religious leaders contribute to secular wars and terrorism by endorsing or supporting the violence

- Religious fervor is exploited by secular leaders to support war and terrorism

Byron Bland asserts that one of the most prominent reasons for the "rise of the secular in Western thought" was the reaction against the religious violence of the 16th and 17th centuries. He asserts that "(t)he secular was a way of living with the religious differences that had produced so much horror. Under secularity, political entities have a warrant to make decisions independent from the need to enforce particular versions of religious orthodoxy. Indeed, they may run counter to certain strongly held beliefs if made in the interest of common welfare. Thus, one of the important goals of the secular is to limit violence."[12]

While it is true that violence and oppression have been carried out in the name of Christianity throughout history, there continues to be disagreement about whether such acts are really justified by Christian teachings or simply evil acts perpetrated by people claiming to be Christians. Miroslav Volf acknowledges that "many contemporaries see religion as a pernicious social ill that needs aggressive treatment rather than a medicine from which cure is expected." However, Volf contests this claim that "(the) Christian faith, as one of the major world religions, predominantly fosters violence." Instead of this negative assessment, Volf argues that Christianity "should be seen as a contributor to more peaceful social environments."[13]

Many authors highlight the ironical contradiction between Christianity's claims to be centered on "love and peace" while, at the same time, harboring a "violent side". For example, Mark Juergensmeyer argues: "that despite its central tenets of love and peace, Christianity—like most traditions—has always had a violent side. The bloody history of the tradition has provided images as disturbing as those provided by Islam orSikhism, and violent conflict is vividly portrayed in the Bible. This history and these biblical images have provided the raw material for theologically justifying the violence of contemporary Christian groups. For example, attacks on abortion clinics have been viewed not only as assaults on a practice that Christians regard as immoral, but also as skirmishes in a grand confrontation between forces of evil and good that has social and political implications."[14]: 19–20 , sometimes referred to as Spiritual warfare. The statement attributed to Jesus "I come not to bring peace, but to bring a sword" has been interpreted by some as a call to arms to Christians.[14]

Maurice Bloch also argues that Christian faith fosters violence because Christian faith is a religion, and religions are by their very nature violent; moreover, he argues that religion and politics are two sides of the same coin—power.[15] Similarly, Hector Avalos argues that, because religions claim divine favor for themselves, over and against other groups, this sense of righteousness leads to violence because conflicting claims to superiority, based on unverifiable appeals to God, cannot be adjudicated objectively.[2]

Regina Schwartz argues that all monotheistic religions, including Christianity, are inherently violent because of an exclusivism that inevitably fosters violence against those that are considered outsiders.[16] Lawrence Wechsler asserts that Schwartz isn't just arguing that Abrahamic religions have a violent legacy, but that the legacy is actually genocidal in nature.[17]

In response, Christian apologists such as Miroslav Volf and J. Denny Weaver reject charges that Christianity is a violent religion, arguing that certain aspects of Christianity might be misused to support violence but that a genuine interpretation of its core elements would not sanction human violence but would instead resist it. Among the examples that are commonly used to argue that Christianity is a violent religion, J. Denny Weaver lists "(the) crusades, the multiple blessings of wars, warrior popes, support for capital punishment, corporal punishment under the guise of 'spare the rod and spoil the child,' justifications of slavery, world-wide colonialism in the name of conversion to Christianity, the systemic violence of women subjected to men". Weaver characterizes the counter-argument as focusing on "Jesus, the beginning point of Christian faith,... whose Sermon on the Mount taught nonviolence and love of enemies,; who faced his accusers nonviolent death;whose nonviolent teaching inspired the first centuries of pacifist Christian history and was subsequently preserved in the justifiable war doctrine that declares all war as sin even when declaring it occasionally a necessary evil, and in the prohibition of fighting by monastics and clergy as well as in a persistent tradition of Christian pacifism."[5]

Miroslav Volf has examined the question of whether Christianity fosters violence, and has identified four main arguments that it does: that religion by its nature is violent, which occurs when people try to act as "soldiers of God"; that monotheism entails violence, because a claim of universal truth divides people into "us versus them"; that creation, as in the Book of Genesis, is an act of violence; and that the intervention of a "new creation", as in the Second Coming, generates violence.[1] Writing about the latter, Volf says: "Beginning at least with Constantine's conversion, the followers of the Crucified have perpetrated gruesome acts of violence under the sign of the cross. Over the centuries, the seasons of Lent and Holy Week were, for the Jews, times of fear and trepidation; Christians have perpetrated some of the worst pogroms as they remembered the crucifixion of Christ, for which they blamed the Jews. Muslims also associate the cross with violence; crusaders' rampages were undertaken under the sign of the cross."[18] In each case, Volf concluded that the Christian faith was misused in justifying violence. Volf argues that "thin" readings of Christianity might be used mischievously to support the use of violence. He counters, however, by asserting that "thick" readings of Christianity's core elements will not sanction human violence and would, in fact, resist it.[1]

Volf asserts that Christian churches suffer from a "confusion of loyalties". He asserts that "rather than the character of the Christian faith itself, a better explanation of why Christian churches are either impotent in the face of violent conflicts or actively participate in them derives from the proclivities of its adherents which are at odds with the character of the Christian faith." Volf observes that "(although) explicitly giving ultimate allegiance to the Gospel of Jesus Christ, many Christians in fact seem to have an overriding commitment to their respective cultures and ethnic groups."[19]

William Cavanaugh asserts that "the idea that religion has a tendency to promote violence is part of the conventional wisdom of Western societies and it underlies many of our institutions and policies, from limits on the public role of churches to efforts to promote liberal democracy in the Middle East." Cavanaugh challenges this conventional wisdom, arguing that there is a "myth of religious violence", basing his argument on the assertion that "attempts to separate religious and secular violence are incoherent."[20]

John Teehan takes a position that integrates the two opposing sides of this debate. He describes the traditional response in defense of religion as "draw(ing) a distinction between the religion and what is done in the name of that religion or its faithful." Teehan argues that "this approach to religious violence may be understandable but it is ultimately untenable and prevents us from gaining any useful insight into either religion or religious violence." He takes the position that "violence done in the name of religion is not a perversion of religious belief... but flows naturally from the moral logic inherent in many religious systems, particularly monotheistic religions..." However, Teehan acknowledges that "religions are also powerful sources of morality." He asserts that "religious morality and religious violence both spring from the same source, and this is the evolutionary psychology underlying religious ethics."[21]

Christian scriptures

[edit]From its earliest days, Christianity has been challenged to reconcile the scriptures known as the "Old Testament" with the scriptures known as the "New Testament". Ra'anan S. Boustan asserts that "(v)iolence can be found throughout the pages of the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) and the New Testament."[22] Philip Jenkins describes the Bible as overflowing with "texts of terror".[23]

In response to these charges of violence in their scriptures, many Christian theologians and apologists respond that the "God of the Old Testament" is a violent God whereas the "God of the New Testament" is a peaceful and loving God. Gibson and Matthews characterize this view as a "millenia-old bias", one that "places the origins of Judeo-Christian violence squarely within Judaism".[24]

Terence Freitheim describes the Old Testament as a "book filled with ...the violence of God". He asserts that while the New Testament does not have the same reputation, it too is "filled with violent words and deeds, and Jesus and the God of the New Testament are complicit in this violence.[7] Gibson and Matthews have a similar perspective.[24]

Gibson and Matthews make a similar charge, asserting that many studies of violence in the Bible focus on violence in the Old Testament while ignoring or giving little attention to the New Testament. They find even more troubling "those studies that lift up the New Testament as somehow containing the antidote for Old Testament violence."[25]

This apparent contradiction in the sacred scriptures between a "God of vengeance" and a "God of love" are the basis of a tension between the irenic and eristic tendencies of Christianity that has continued to the present day.

This approach is challenged by those who point out that there are also passages in the New Testament that tolerate, condone and even encourage the use of violence. John Hemer asserts that the two primary approaches that Christian teaching uses to deal with "the problem of violence in the Old Testament" are:

- Concentrate more on the many passages where God is depicted as loving – much of Isaiah, Hosea, Micah, Deuteronomy.

- Explain how the idea of God as a violent punishing war monger is all part of the historical and cultural conditioning of the author and that we can ignore it in good faith, especially in the light of the New Testament.

In opposition to these two approaches, Hemer argues that to ignore or explain away the violence found in the Old Testament is a mistake. He asserts that "Violence is not peripheral to the Bible it is central, in many ways it is the issue, because of course it is the human problem." He concludes by saying that "The Bible is in fact the story of the slow, painstaking and sometimes faltering escape from the idea of a God who is violent to a God who is love and has absolutely nothing to do with violence."[26] Ronald Clements expresses a similar view, writing that "to dismiss the biblical language concerning the divine wrath as inappropriate, or even offensive, to the modern religious mind achieves nothing at all by way of resolving the tensions in the reality of human history and human experience.[27]

Old Testament

[edit]The principle of "an eye for an eye" is often referred to using the Latin phrase lex talionis, the law of talion. The meaning of the principleEye for an Eye is that a person who has injured another person returns the offending action to the originator in compensation. The exact Latin(lex talionis) to English translation of this phrase is actually "The law of retaliation." At the root of this principle is that one of the purposes of the law is to provide equitable retribution for an offended party.

Christian interpretation of the Biblical passage has been heavily influenced by the quotation from Leviticus (19:18 above) in Jesus of Nazareth's Sermon on the Mount. In the Expounding of the Law (part of the Sermon on the Mount), Jesus urges his followers to turn the other cheek when confronted by violence:

You have heard that it was said, "An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth". But I say to you, do not resist an evildoer. If anyone strikes you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also. (Matthew 5:38–39, NRSV)

This saying of Jesus is frequently interpreted as criticism of the Old Testament teaching, and often taken as implying that "an eye for an eye" encourages excessive vengeance rather than an attempt to limit it. It was one of the points of 'fulfilment or destruction' of the Hebrew law which the Church father St. Augustine already discussed in his Contra Faustum, Book XIX.[28]

Dr Ian Guthridge cited many instances of genocide in the Old Testament:[29]: 319–320

| “ | the Bible also contains the horrific account of what can only be described as a "biblical holocaust". For, in order to keep the chosen people apart from and unaffected by the alien beliefs and practices of indigenous or neighbouring peoples, when God commanded his chosen people to conquer the Promised Land, he placed city after city 'under the ban" -which meant that every man, woman and child was to be slaughtered at the point of the sword. | ” |

The extent of extermination is described in the scriptural passage Deut 20:16–18 which orders the Israelites to "not leave alive anything that breathes… completely destroy them …".[30] thus leading many scholars to characterize the exterminations as genocide.[31] [32] [33] [34] [35] [36] [37] [38] [39] [40] Niels Peter Lemche asserts that European colonialism in the 19th century was ideologically based on the Old Testament narratives of conquest and extermination.[41]Arthur Grenke claims that the view or war expressed in Deuteronomy contributed to the destruction of Native Americans and to the destruction of European Jewry.[42]

The image of a violent God in Hebrew scriptures that condoned and even ordered violence posed a problem for some early Christians who saw this as a direct contradiction to the God of peace and love attested to in the New Testament. Perhaps the most famous example was Marcion who dropped the Hebrew scriptures from his version of the Bible because he found in them a violent God. Marcion saw the God of the Old Testament, the Demiurge and creator of the material universe, as a jealous tribal deity of the Jews, whoselaw representedlegalistic reciprocal justice and who punishes mankind for its sins by suffering and death. Marcion wrote that the God of the Old Testament was an "uncultured, jealous, wild, belligerent, angry and violent God, who has nothing in common with the God of the New Testament..." For Marcion, the God about whom Jesus was an altogether different being, a universal God of compassion and love, who looks upon humanity with benevolence and mercy. Marcion argued that Christianity should be solely based on Christian Love. He went so far as to say that Jesus’ mission was to overthrow Demiurge -- the fickle, cruel, despotic God of the Old Testament—and replace Him with the Supreme God of Love whom Jesus came to reveal.[43]

Marcion's teaching was repudiated by Tertullian in five treatises titled "Against Marcion" and Marcion was ultimately excommunicated by the Church of Rome.[44]

The difficulty posed by the apparent contradiction between the God of the Old Testament and the God of the New Testament continues to perplex pacifist Christians to this day. Eric Seibert asserts that, "(f)or many Christians, involvement in warfare and killing in the pages of the Old Testament is incontrovertible evidence that such activities have God's blessing. ... Attitudes like this are terribly troubling to religious pacifists and demonstrate the kind of problems these texts create for them."[45] Some modern-day pacifists such as Charles Raven have argued that the Church should repudiate the Old Testament as an unchristian book, thus echoing the approach taken by Marcion in the 2nd century.[46]

New Testament

[edit]Gedaliahu G. Stroumsa asserts that it is well known that both 'irenic' and 'eristic' (i.e. peaceful and aggressive) tendencies co-exist in the New Testament.[47] Stroumsa cites the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5:43–48,Luke 6:25–33) as an example of an eristic passage in the New Testament.[47] As further examples of eristic scriptures, Stroumsa cites the following Gospel passages:[47]:

- Do not think that I have come to bring peace to the earth; I have not come to bring peace but a sword.Matthew 10:34

- I came to bring fire to the earth and how I wish it were already kindled! Do you think that I have come to bring peace to the earth? No, I tell you, but rather division.Luke 12:49–51

Ra'anan S. Boustan cites the passage where Jesus foretells a time when "children will rise up against their parents and have them put to death (Matthew 10:21,34–37,Luke 12:51–53)"

In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus is quoted as saying, "'do not resist an evil person. If someone strikes you on the right cheek, turn to them the other also". (Matthew 6:39) and "Put your sword back in its place.. for all who draw the sword will die by the sword." (Matthew 26:52).

Other sayings and acts of Jesus that have been cited as examples of tacit acceptance of violence include: the absence of any censure of the soldier who asks Jesus to heal his servant, his overturning the tables and chasing the moneychangers from the temple with a rope in his hand, and through his Apostles, baptising a Roman Centurion who is never asked to first give up arms.[48]

W.E. Addis cites the case of the soldiers instructed by in their duties by St. John the Baptist, and that of the military men whom Christ and His Apostles loved and familiarly conversed with (Luke 3:14, Acts 10, Matthew 8:5), without a word to imply that their calling was unlawful, sufficiently prove the point."[48]

Ra'anan S. Boustan cites the "apocalyptic vision of Revelation which imagines one third of the world's population being killed.(Revelation 9:15)."[22] According to Steve Friesen, the Book of Revelation has been employed in a wide array of settings, many of which have been lethal. Among these, Friesen lists Christian hostility, Christian imperialism and Christian sectarian violence.[49]

Christian teaching

[edit]Theologian Robert McAfee Brown identifies a succession of three basic attitudes towards violence and war during the history of Christian thought. The first of these attitudes was the strict pacifism of the earliest Christians; by the 3rd century, this pacifism had evolved to incorporate the concept of a just war which then led to the development of the holy war or crusade.[50]

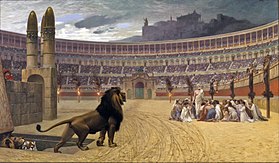

Pacifism in early Christianity

[edit]Many scholars assert that Early Christianity (prior to 313 AD) was a pacifist religion and that, only after it had become the state religion of the Roman Empire, did Christianity begin to rationalize, institutionalize and endorse violence to further the interests of the state and the church. Some scholars believe that "the accession of Constantine terminated the pacifist period in church history."[51] According to Rene Girard, "Beginning with Constantine, Christianity triumphed at the level of the state and soon began to cloak with its authority persecutions similar to those in which the early Christians were victims."[52]

In response to the accusations of Richard Dawkins, Alister McGrath suggests that, far from endorsing "out-group hostility",Jesus commanded an ethic of "out-group affirmation". McGrath agrees that it is necessary to critique religion, but says that it possesses internal means of reform and renewal, and argues that, while Christians may certainly be accused of failing to live up to Jesus' standard of acceptance, Christian ethics reject violence.[53]

In the first few centuries of Christianity, many Christians refused to engage in military combat. In fact, there were a number of famous examples of soldiers who became Christians and refused to engage in combat afterward. They were subsequently executed for their refusal to fight.[54] The commitment to pacifism and rejection of military service is attributed by Allman and Allman to two principles: "(1) the use of force (violence) was seen as antithetical to Jesus' teachings and service in the Roman military required worship of the emperor as a god which was a form of idolatry."[55]

Origen asserted: "Christians could never slay their enemies. For the more that kings, rulers, and peoples have persecuted them everywhere, the more Christians have increased in number and grown in strength."[56]Clement of Alexandria wrote: "Above all, Christians are not allowed to correct with violence."[57] Tertullian argued forcefully against all forms of violence, considering abortion, warfare and even judicial death penalties to be forms of murder.[58][59]

Non-violence as a Christian doctrine

[edit]

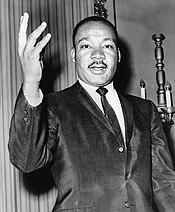

There is a long tradition of opposition to violence in Christianity.[60] Some early figures in Christian thought explicitly disavowed violence. Origen wrote: "Christians could never slay their enemies. For the more that kings, rulers, and peoples have persecuted them everywhere, the more Christians have increased in number and grown in strength."[56] Clement of Alexandriawrote: "Above all, Christians are not allowed to correct with violence."[57] Several present-day Christian churches and communities were established specifically with nonviolence, including conscientious objection to military service, as foundations of their beliefs.[61] In the 20th century,Martin Luther King, Jr.adapted the nonviolent ideas of Gandhi to a Baptist theology and politics.[62] In the 21st century, Christian feministthinkers have drawn attention to opposing violence against women.[63]

Some theologians, however, reject the pacifist interpretation of Christian dogma. W.E. Addis et al. have written: "There have been sects, notably the Quakers, which have denied altogether the lawfulness of war, partly because they believe it to be prohibited by Christ (Mt. v. 39, etc), partly on humanitarian grounds. On the Scriptural ground they are easily refuted; the case of the soldiers instructed by in their duties by St. John the Baptist, and that of the military men whom Christ and His Apostles loved and familiarly conversed with (Lk 3:14, Acts 10, Mt 8:5), without a word to imply that their calling was unlawful, sufficiently prove the point."[48]

Just war theory

[edit]Just War Theory' (or Bellum iustum) is a doctrine of military ethics of Roman philosophical andCatholic origin[64][65] studied by moral theologians, ethicists and international policy makers which holds that a conflict can and ought to meet the criteria of philosophical, religious or political justice, provided it follows certain conditions.

Just War theorists combine both a moral abhorrence towards war with a readiness to accept that war may sometimes be necessary. The criteria of the just war tradition act as an aid to determining whether resorting to arms is morally permissible. Just War theories are attempts "to distinguish between justifiable and unjustifiable uses of organized armed forces"; they attempt "to conceive of how the use of arms might be restrained, made more humane, and ultimately directed towards the aim of establishing lasting peace and justice."[66]

The Just War tradition addresses the morality of the use of force in two parts: when it is right to resort to armed force (the concern of jus ad bellum) and what is acceptable in using such force (the concern of jus in bello).[67] In more recent years, a third category — jus post bellum — has been added, which governs the justice of war termination and peace agreements, as well as the prosecution of war criminals.

The concept of justification for war under certain conditions goes back at least to Cicero.[68] However its importance is connected to Christian medieval theory beginning from Augustine of Hippo and Thomas Aquinas.[69] According to Jared Diamond, Saint Augustine played a critical role in delineating Christian thinking about what constitutes a just war, and about how to reconcile Christian teachings of peace with the need for war in certain situations.[70]

Jonathan Riley Smith writes,

The consensus among Christians on the use of violence has changed radically since the crusades were fought. The just war theory prevailing for most of the last two centuries — that violence is an evil which can in certain situations be condoned as the lesser of evils — is relatively young. Although it has inherited some elements (the criteria of legitimate authority, just cause, right intention) from the older war theory that first evolved around a.d. 400, it has rejected two premises that underpinned all medieval just wars, including crusades: first, that violence could be employed on behalf of Christ's intentions for mankind and could even be directly authorized by him; and second, that it was a morally neutral force which drew whatever ethical coloring it had from the intentions of the perpetrators.[71]

Holy war

[edit]

In 1095, at the Council of Clermont, Pope Urban II declared that some wars could be deemed as not only a bellum iustum ("just war"), but could, in certain cases, rise to the level of a bellum sacrum(holy war).[72] Jill Claster characterizes this as a "remarkable transformation in the ideology of war", shifting the justification of war from being not only "just" but "spiritually beneficial.[73] Thomas Murphy examined the Christian concept of Holy War, asking "how a culture formally dedicated to fulfilling the injunction to 'love thy neighbor as thyself' could move to a point where it sanctioned the use of violence against the alien both outside and inside society". The religious sanctioning of the concept of "holy war" was a turning point in Christian attitudes towards violence; "Pope Gregory VII made the Holy War possible by drastically altering the attitude of the church towards war... Hitherto a knight could obtain remission of sins only by giving up arms, butUrban invited him to gain forgiveness 'in and through the exercise of his martial skills'". A Holy War was defined by the Roman Catholic Church as "war that is not only just, but justifying; that is, a war that confers positive spiritual merit on those who fight in it".[74][75]

In the 12th century, Bernard of Clairvaux wrote: "'The knight of Christ may strike with confidence and die yet more confidently; for he serves Christ when he strikes, and saves himself when he falls.... When he inflicts death, it is to Christ's profit, and when he suffers death, it is his own gain."[76]

According to Daniel Chirot, the Biblical account of Joshua and the Battle of Jericho was used to justify the genocide of Catholics during the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland.[77]: 3 Chirot also interprets 1 Samuel15:1–3 as "the sentiment, so clearly expressed, that because a historical wrong was committed, justice demands genocidal retribution."[77]: 7–8

Sins punishable by death

[edit]Blasphemy

[edit]St. John Chrysostom wrote:

- Should you hear any one in the public thoroughfare, or in the midst of the forum, blaspheming God; go up to him and rebuke him; and should it be necessary to inflict blows, spare not to do so. Smite him on the face; strike his mouth; sanctify your hand with the blow, and if any should accuse you, and drag you to the place of justice, follow them there; and when the judge on the bench calls you to account, say boldly that the man blasphemed the King of angels! For if it be necessary to punish those who blaspheme an earthly king, much more so those who insult God. It is a common crime, a public injury; and it is lawful for every one who is willing, to bring forward an accusation. Let the Jews and Greeks learn, that the Christians are the saviors of the city; that they are its guardians, its patrons, and its teachers. Let the dissolute and the perverse also learn this; that they must fear the servants of God too; that if at any time they are inclined to utter such a thing, they may look round every way at each other, and tremble even at their own shadows, anxious lest perchance a Christian, having heard what they said, should spring upon them and sharply chastise them.[78]

Blasphemy against God and the Church was a crime punishable by death in much of Europe.

Homosexuality

[edit]European Christian scholars have historically argued that the crime of homosexuality should be punishable by death, based upon passages in the Bible.[79] Canon law called for capital punishment for homosexuality based on the findings of Christian legal scholars: "Bishop Wala, the leading churchman of the Frankish kingdom, convened the Council at Paris... the council explicitly endorsed the death penalty for sodomy. Moreover, Canon 34 not only endorsed Leviticus but also interpreted Paul's Epistle to the Romans as advocating capital punishment.... Paulaccuses non-believers of a long list of sins, in which homosexuality is given a special prominence. Then he adds that the 'judgement of God' makes such sinners 'worthy of death.'"[79] Saint Thomas argued that homosexuality, even between consenting adults, was immoral and an offence of heresy against God, and therefore punishable by death (as heresy was).[80]

Early Christianity

[edit]Elizabeth Castelli asserts that " Christianity itself is founded upon an archetype of religio-political persecution, the execution of Jesus by the Romans." She points out that " the earliest Christians routinely equated Christian identity with suffering persecution" as attested by numerous passages in the New Testament. As examples, she cites the passage in the Sermon on the Mount where Jesus says, “Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are you when men revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you falsely on my account” (Matthew 5.10-11). As another example, she cites the passage in the Gospel of John where Jesus warns his disciples with these words: “Remember the word that I said to you: ‘A servant is not greater than his master.’ If they persecuted me, they will persecute you” (John 15.20).

Michael Gaddis writes:

The Christian experience of violence during the pagan persecutions shaped the ideologies and practices that drove further religious conflicts over the course of the fourth and fifth centuries... The formative experience of martyrdom and persecution determined the ways in which later Christians would both use and experience violence under the Christian empire. Discourses of martyrdom and persecution formed the symbolic language through which Christians represented, justified, or denounced the use of violence."[81]

Apostolic Age

[edit]The persecution of Christians in the Apostolic Age is an important part of the Early Christiannarrative which depicts the early Church as being persecuted for their heterodox beliefs by an alleged "Jewish establishment" in what was then Roman occupied Iudaea province. This account of persecution is part of a general theme of a polemic against the Jews that starts with the Pharisaic rejection of Jesus's ministry and continues on with his trial before the High Priest, his crucifixion, and the Pharisees' refusal to accept him as the Jewish Messiah. Some have argued that this anti-Judaism in the New Testament would later become the justification for anti-semitism.

Persecution by the Romans

[edit]

In its first three centuries, the Christian church endured periods of persecution at the hands of Romanauthorities. Christians were persecuted by local authorities on an intermittent and ad-hoc basis. In addition, there were several periods of empire-wide persecution which was directed from the seat of government in Rome.

Christians were the targets of persecution because they refused to worship the Roman gods or to pay homage to the emperor as divine. In the Roman empire, refusing to sacrifice to the Emperor orthe empire's gods was tantamount to refusing to swear an oath of allegiance to one's country.

Some early Christians sought out and welcomed martyrdom. Such seeking after death is found in Tertullian's Scorpiace but was certainly not the only view of martyrdom in the Christian church. Both Polycarp and Cyprian, bishops in Smyrna and Carthage respectively, attempted to avoid martyrdom.[citation needed] However, an overwhelming majority of Christians did not choose to die for their faith during the persecutions.

Persecution of pagans in late antiquity

[edit]Constantine supported the church with his patronage; he had an extraordinary number of large basilicas built for the Christian church, and endowed it with land and other wealth.[82] In doing this, however, he required the Pagans "to foot the bill".[82] According to Christian chroniclers it appeared necessary to Constantine "to teach his subjects to give up their rites (...) and to accustom them to despise their temples and the images contained therein,"[83] which led to the closure of pagan temples due to a lack of support, their wealth flowing to the imperial treasure;[84]Constantine I did not need to use force to implement this,[82] although his subjects are said to simply have obeyed him out of fear. Only the chronicler Theophanes has added that temples "were annihilated", but this is considered "not true" by contemporary historians.[85] According to the historian Ramsay MacMullen Constantine desired to obliterate non-Christians but lacking the means he had to be content with robbing their temples towards the end of his reign.[86] The leader of the Egyptian monks who participated in the sack of temples replied to the victims who demanded back their sacred icons: "I peacefully removed your gods...there is no such thing as robbery for those who truly possess Christ.[87]

At the turn of the century St Augustine would exhort his congregation in Carthage to smash all tangible symbols of paganism they could lay their hands on "for that all superstition of pagans and heathens should be annihilated is what God wants, God commands, God proclaims!" – words uttered to wild applause, and possibly the cause of religious riots resulting in sixty deaths. It is estimated that pagans still made up half of the Empire's population.[87][88]

In 435, Theodosius II decreed that all “heretics” and pagans be put to death. The only legal religion other than Christianity was Judaism. In 451, Theodosius II further decreed that idolatry be punishable by death.

Suppression of heresies

[edit]In the 2nd century, Irenaeus wrote a treatise against the Gnostics, titled [[ Adversus Haereses]] (Against Heresies). He is generally considered to be the first writer to use the term heresy to designate belief that was outside the orthodox teaching of the Church. Once Christianity became recognized as the official state religion of the Roman Empire, it moved to outlawpaganism and non-orthodox Christian beliefs. [89]

Even with its legal advantage, it took several centuries to stamp out unorthodox Christian beliefs such as Novatianism and Gnosticism.[90] Eventually, the Roman emperor intervened in the case of major doctrinal disputes such as the conflict between orthodox and Arian Christianity.[90] James R. Lewis attributes the Church's vehement reaction against the emergence of new heresies in the 11th century to the memory of the Church's struggle against heresy in late antiquity. In contrast to the late antiquity, the execution of heretics was much more easily approved in the lateMiddle Ages.[89] The first known case is the burning of fourteen people at Orléans in 1022.[91] In the following centuries groups like the Bogomils, Waldensians,Cathars and Lollards were persecuted throughout Europe. The Fourth Council of the Lateran (1215) codified the theory and practise of persecution.[91] In its third canon, the council declared:"Secular authorities, whatever office they may hold, shall be admonished and induced and if necessary compelled by ecclesiastical censure, .. to take an oath that they will strive .. to exterminate in the territories subject to their jurisdiction all heretics pointed out by the Church."[92]

Saint Thomas Aquinas summed up the standard medieval position, when he declared that that obstinate heretics deserved "not only to be separated from the Church, but also to be eliminated from the world by death" [93]

Christian theologians such as Augustine of Hippo and Thomas Aquinas had legitimized religious persecution to various extents and, during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, Christians considered heresy anddissent to be punishable offences. However,Early modern Europe witnessed the turning point in the Christian debate on persecution and toleration. Christian writers like John Milton andJohn Locke argued for limited religious toleration, and later authors like Thomas Jefferson developed the concept of religious freedom. Christians nowadays generally accept that heresy and dissent are not punishable by a civil authority. Many Christians "look back on the centuries of persecution with a mixture of revulsion and incomprehension."[94]

Early Christianity

[edit]Irenaeus, the Bishop of Lyons, recorded the violent battles between Christians of various cities, the betrayal and assassinations of religious leaders, and the confusion over basic doctrines of Christianity. [95]

Late antiquity

[edit]During the course of his life, Constantine progressively became more Christian and turned away from any syncretic tendencies he appeared to favour at times and thus demonstrating, according to his biographers, that "The God of the Christians was indeed a jealous God who tolerated no other gods beside him. The Church could never acknowledge that she stood on the same plane with other religious bodies, she conquered for herself one domain after another".[96]

Subsequent Christian Roman Emperors sanctioned "attacks on pagan worship".[90] Towards the end of the 4th century Theodosius worked to establish Catholicism as the privileged religion in the Roman Empire."Theodosius was not the man to sympathise with the balancing policy of the Edict of Milan. He set himself steadfastly to the work of establishing Catholicism as the privileged religion of the state, of repressing dissident Christians (heretics) and of enacting explicit legal measures to abolish Paganism in all its phases."[97]

Two hundred and fifty years after Constantine was converted and began the long campaign of official temple destruction and outlawing of non-Christian worship Justinian was still engaged in the war of dissent.[98]

Between 430 and 630, the Christian world was torn apart by a series of sectarian wars that included coups and rebellions, urban riots and pogroms, beheadings and burnings.[99]

Bart Ehrman writes:

... the internal Christian conflicts were struggles over power, not just theology. And the side that knew how to utilize power was the side that won. More specifically, Bauer pointed out that the Christian community in Rome was comparatively large and affluent. Moreover, located in the capital of the empire, it had inherited a tradition of administrative prowess [...]. Using the administrative skills of its leaders and its vast material resources, the church in Rome managed to exert influence over other Christian communities. Among other things, the Roman Christians promoted a hierarchical structure, insisting that each church should have a single bishop. [...] By paying for the manumission of slaves and purchasing the freedom of prisoners, the Roman church brought large numbers of grateful converts into the fold, while the judicious use of gifts and alms offered to other churches naturally effected a sympathetic hearing of their views. [...] By the end of the third century, the Roman form of Christianity had established dominance.[100]

Theodosius I

[edit]The first known usage of the term 'heresy' in a civil legal context was in 380 AD by the "Edict of Thessalonica" of Theodosius I. Prior to the issuance of this edict, the Church had no state sponsored support for any particular legal mechanism to counter what it perceived as 'heresy'. By this edict, in some senses, the line between the Catholic Church's spiritual authority and the Roman State's jurisdiction was blurred. One of the outcomes of this blurring of Church and State was a sharing of State powers of legal enforcement between Church and State authorities. At its most extreme reach, this new legal backing of the Church gave its leaders the power to, in effect, pronounce the death sentence upon those whom they might perceive to be 'heretics'. Within 5 years of the official 'criminalization' of heresy by the emperor, the first Christian heretic,Priscillian was executed in 385 by Roman officials. Ramsey MacMullen observes that in the century that opened the Peace of Christ more Christians died at the hands of their fellow Christians than the sum total of all who died during the preceding centuries of persecution.[101]

The intolerance of Theodosius I is attributed by some to Ambrose who is characterized as "a bigot in whose eyes Jews, heretics and pagans had no rights."[102]

The Augustinian consensus

[edit]The transformation that happened in the 4th century lies at the heart of the debate between those Christian authors who advocated religious persecution and those who rejected it.[90] Most of all, the advocates of persecution looked to the writings of Augustine of Hippo,[90] the most influential of the Christian Church Fathers.[103] Initially (in the 390s), Augustine had been sceptical about the use of coercion in religious matters. However, he changed his mind after he had witnessed the way that the Donatists (a schismatic Christian sect) had been "brought over to the Catholic unity by fear of imperial edicts." From a position that had trusted the power of philosophical argumentation, Augustine had moved to a position that emphasised the authority of the church.[104] Augustine had become convinced of the effectiveness of mild forms of persecution and developed a defence of their use. His authority on this question was undisputed for over a millennium inWestern Christianity.[90] Within this Augustinian consensus there was only disagreement about the extent to which Christians should persecute heretics. Augustine advocated fines, imprisonment, banishment and moderate floggings, but, according to Henry Chadwick, "would have been horrified by the burning of heretics."[105] In late Antiquity those burnings appear very rare indeed, the only certain case being the execution of Priscillian and six of his followers in 385. This sentence was roundly condemned by bishops likeAmbrose, Augustine's mentor.[91]

Albigensian Crusade

[edit]Jonathan Barker cited the Albigensian Crusade, launched by Pope Innocent III against followers of Catharism, as an example of Christianstate terrorism.[106] The 20 year war led to an estimated 1 million casualties.[107]

Inquisition

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2010) |

Christian leaders and Christian doctrines have been accused of justifying and perpetrating violence during the Inquisition.[108] [109] [110] A legal basis for some inquisitorial activity came from Pope Innocent IV's papal bull Ad exstirpanda of 1252, which authorized and regulated the use of torture in investigating heresy. The inquisition expanded in size and scope following the 12th century in response to the Church's fears that heretics were exerting improper and harmful influence on members of the church. The inquisition was initially used by the church to help it identify persons that were heretics. Later, the Church expanded the inquisition to include torture as a way to determine the guilt of suspected heretics.[111]

John Teehan characterizes the Spanish Inquisition as "one of the most virulent examples of religious violence in history".[112] Established in 1478, the Spanish Inquisition was originally intended in large part to ensure the orthodoxy of those who converted from Judaism and Islam. This regulation of the faith of the newly converted was intensified after the royal decrees issued in 1492 and 1501 ordering Jews and Muslims to convert or leave. Although the Inquisition was technically forbidden from permanently harming or drawing blood, this still allowed for methods of torture.[113]

Witch hunts

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2010) |

The Witch trials in the Early Modern period were a period of witch hunts that occurred between the 15th and 18th centuries,[116]when across Early Modern Europe, and to some extent in the European colonies in North America, there was a widespread hysteria that malevolentSatanic witches were operating as an organized threat to Christendom. Over the entire duration of the phenomenon of some four centuries, an estimated total of 40,000 to 60,000 people were executed. Three developments in Christian doctrine have been identified as factors contributing significantly to the witch hunts: 1) a shift from the rejection of belief in witches to an acceptance of their existence and powers, 2) developments in the doctrine of Satan which incorporated witchcraft as part of Satanic influence, 3) the identification of witchcraft as heresy.

Belief in witches and supernatural evil were widespread in medieval Europe,[117] and the secular legal codes of European countries had identified witchcraft as a crime before being reached by Christian missionaries.[118] Scholars have noted that the early influence of the Church in the medieval era resulted in the revocation of these laws in many places,[119][120] bringing an end to traditional pagan witch hunts.[121] Throughout the medieval era mainstream Christian teaching denied the existence of witches and witchcraft, condemning it as pagan superstition.[122] Notable instances include an Irish synod in 800,[123] Agobard of Lyons,[124] Pope Gregory VII,[125] and Serapion of Vladimire.[126] The traditional accusations and punishments were likewise condemned.[127][128] Historian Brian Hutton therefore exculpates the early Church from responsibility for the witch hunts, arguing that this was the result of doctrinal change in the later Church.[129]

However, Christian influence on popular beliefs in witches and maleficium (harm committed by magic), failed to eradicate traditional beliefs,[130] and developments in the Church doctrine of Satan proved influential in reversing the previous dismissal of witches and witchcraft as superstition; instead these beliefs were incorporated into an increasingly comprehensive theology of Satan as the ultimate source of all maleficium.[131][132] The work of Thomas Aquinas in the 13th century was instrumental in developing the new theology which would give rise to the witch hunts,[133] but due to the fact that sorcery was judged by secular courts it was not untilmaleficium was identified with heresy that theological trials for witchcraft could commence.[134] Despite these changes the doctrinal shift was only completed in the 15th century,[135] when it first began to result in Church-inspired witch trials.[136] Promulgation of the new doctrine by Henricus Institoris met initial resistance in some areas,[137] and some areas of Europe only experienced the first wave of the new witch trials in the latter half of the 16th century.[138][139]

Military orders

[edit]Military orders are Christian societies of knights that founded for the purpose of crusading, i.e. propagating and/or defending thefaith by military means either in the Holy Land or against Islam (Reconquista) or pagans (mainlyBaltic region) inEurope. Some of the more famous military orders include the Knights Templar, the Knights Hospitaller and the Teutonic Knights.

Religious wars against non-Christians

[edit]Crusades

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2010) |

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2010) |

The Crusades were a series of religiously sanctioned military campaigns waged by much of Roman Catholic Europe between 1095 and 1291. The Crusades were fought mainly by Roman Catholic forces (taking place after the East-West Schism and mostly before the Protestant Reformation) against Muslims who had occupied the near east, although campaigns were also waged against pagan Slavs, pagan Balts, Jews, Russian and Greek Orthodox Christians, Mongols,Cathars, Hussites, Waldensians, Old Prussians, and political enemies of the various popes.[140][page needed] Orthodox Christians also took part in fighting against Islamic forces in some Crusades. Crusaders took vows and were granted penance for past sins, often called an indulgence.[140][page needed][141][page needed]

The Crusades had far-reaching political, economic, and social impacts, some of which have lasted into contemporary times. Because of internal conflicts among Christian kingdoms and political powers, some of the crusade expeditions were diverted from their original aim, such as the Fourth Crusade, which resulted in the sack of Christian Constantinople and the partition of the Byzantine Empire between Venice and the Crusaders.

Alan Dershowitz and other analysts assert that Christian leaders relied on Christian doctrines to justify the Crusades.[142] [143] [144]

Some of the Crusades pitted Roman Catholics against Muslims. To this day, the Crusades are still remembered by Muslims as "horrendous atrocities".[145]

In the autumn of 1095, Pope Urban II launched the First Crusade while on a preaching tour of France. He exhorted his audience to join the Crusade, saying: "I say it to those who are present; I command that it be said to those who are absent: Christ commands it. All who go thither and lose their lives, be it on the road or one the sea or in the fight against the pagans, will be granted immediate forgiveness for their sins. This, I grant ... by virtue of the great gift which God has given me." The crowd cried back, "Deus vult, Deus vult" (God wills it, God wills it). Pope Urban responded approvingly, "Yes! Let these words be your war-cry when you unsheath your sword."

When Jerusalem fell to the Crusaders in 1099, the entire population of the city was slaughtered, Muslims and Jews alike. However, recently some scholars have argued that "wholesale slaughter of Jews did not occur".[146]

According to Gus Martin, "the Western Church also purged its territories of Jews and divergent religious beliefs that were denounced as heresies."[147]

Although the Crusades were nominally focused on retaking the Holy Land from the Muslim infidels, Crusaders often perpetrated violent acts against other victims who were more immediately available. For example, European Jews were often victims of Crusader violence in the preparatory stages prior to a Crusade departing for the Holy Land. According to Jonathan Riley-Smith, charismatic preachers who were engaged in raising armies against external enemies used evocative language that encouraged violence against Jews.[148]

Northern Crusades

[edit]The Northern Crusades[149] or Baltic Crusades[150] were crusades undertaken by the Christian kings ofDenmark and Sweden, the German Livonian and Teutonic military orders, and their allies against thepagan peoples of Northern Europe around the southern and eastern shores of the Baltic Sea. Swedish and GermanCatholic campaigns against Russian Eastern Orthodox Christians are also sometimes considered part of the Northern Crusades.[149][151] The east Baltic world was transformed by military conquest: first the Livs, Latgallians and Estonians, then theSemigallians, Curonians, Prussians and the Finns underwent defeat, baptism, military occupation and sometimes extermination by groups of Danes, Germans and Swedes.[152]

Colonialism

[edit]Christianity and colonialism are often closely associated because Catholicism and Protestantism were the religions of the European colonial powers[153] and acted in many ways as the "religious arm" of those powers.[154] Initially, Christian missionaries were portrayed as "visible saints, exemplars of ideal piety in a sea of persistent savagery". However, by the time the colonial era drew to a close in the last half of the 20th century, missionaries becme viewed as “ideological shock troops for colonial invasion whose zealotry blinded them.”[155]

Edward Andrews writes:

Historians have traditionally looked at Christian missionaries in one of two ways. The first church historians to catalogue missionary history provided hagiographic descriptions of their trials, successes, and sometimes even martyrdom. Missionaries were thus visible saints, exemplars of ideal piety in a sea of persistent savagery. However, by the middle of the twentieth century, an era marked by civil rights movements, anti-colonialism, and growing secularization, missionaries were viewed quite differently. Instead of godly martyrs, historians now described missionaries as arrogant and rapacious imperialists. Christianity became not a saving grace but a monolithic and aggressive force that missionaries imposed upon defiant natives. Indeed, missionaries were now understood as important agents in the ever-expanding nation-state, or “ideological shock troops for colonial invasion whose zealotry blinded them.”

According to Jake Meador, "some Christians have tried to make sense of post-colonial Christianity by renouncing practically everything about the Christianity of the colonizers. They reason that if the colonialists’ understanding of Christianity could be used to justify rape, murder, theft, and empire then their understanding of Christianity is completely wrong. "[156]

According to Lamin Sanneh, "(m)uch of the standard Western scholarship on Christian missions proceeds by looking at the motives of individual missionaries and concludes by faulting the entire missionary enterprise as being part of the machinery of Western cultural imperialism." As an alternative to this view, Sanneh presents a different perspective arguing that "missions in the modern era has been far more, and far less, than the argument about motives customarily portrays."[157]

Age of Discovery

[edit]

During the Age of Discovery, the Catholic Church inaugurated a major effort to spread Christianity in the New World and to convert theNative Americans and other indigenous people. The missionary effort was a major part of, and a partial justification for the colonial efforts of Catholic colonial powers such as Spain, France and Portugal.

Jan van Butselaar writes that "for Prince Henry the Navigator and his contemporaries, the colonial enterprise was based on the necessity to develop European commerce and the obligation to propagate the Christian faith."[158]

Christian leaders and Christian doctrines have been accused of justifying and perpetrating violence against Native Americans found in the New World.[142][159] For example, Michael Wood asserts that the indigenous peoples were not considered to be human beings and that the colonisers was shaped by "centuries of Ethnocentrism, and Christian monotheism, which espoused one truth, one time and version of reality.”[160] Similarly, Michael Jordan writes "The catastrophe of Spanish America's rape at the hands of the Conquistadors remains one of the most potent and pungent examples in the entire history of human conquest of the wanton destruction of one culture by another in the name of religion"[161]

Slavery

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (November 2010) |

This article or section possibly contains synthesis of material which does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. (November 2010) |

This section's factual accuracy is disputed. (November 2010) |

The issue of Christianity and slavery is one that has been the subject of intense debate and controversy. Jan van Butselaar writes that "(t)he reputation of Christian faith and ethics was tainted by the cruel violence of European and American slave merchants vis-á-vis their human cargo."[158] Throughout most of human history, slavery has been practiced and accepted by many cultures and religions around the world. Slavery existed in different forms within Christianity for over 18 centuries. In the early years of Christianity, slavery was a normal feature of the economy and society in the Roman Empire, and this remained well into the Middle Ages and beyond.[162] Jennifer Glancy asserts that "we are likely to consider Christian slaveholders as hypocrites and to find the notion of Christian slavery oxymoronic."[163]

The Bible sanctioned the use of regulated slavery in the Old Testament and whether or not the New Testament condemned or sanctioned slavery has been strongly disputed. Passages in the Bible have historically been used by both pro-slavery advocates and slavery abolitionists to support their respective views. Certain passages in the “Old Testament” sanctioned slavery and the “New Testament” gave no clear teaching to indicate that slavery was now prohibited. Most Christian figures in that early period, such as Augustine of Hippo, supported continuing slavery[164] whereas several figures such asSaint Patrick were opposed.

Throughout Christian antiquity and the Middle Ages, theologians generally followed St. Augustine in holding that although slavery could not be justified under natural law it was not absolutely forbidden by that law. In accordance with these teachings, the Roman Catholic Church accepted and condoned certain types of slavery well into the Age of Discovery. As a consequence, the Catholic Church has been criticized for not coming out more forcefully against slavery with some critics dating the end of the Church's acceptance of slavery to 1890 or even as late as 1965.[165] Some scholars argue that the Church did, in fact, oppose slavery starting as early as the Middle Ages. For example, Rodney Stark argues that, "(t)he problem wasn't that the leadership was silent. It was that almost nobody listened."[165]

Christian abolitionists were a principal force in the abolition of slavery. As the abolition movement took shape across the globe, groups who advocated slavery's abolition worked to harness Christian teachings in support of their positions, using both the 'spirit of Christianity', biblical verses against slavery, and textual argumentation.[166]

Middle Ages

[edit]Between the 6th and 12th century there was a growing sentiment that slavery was not compatible with Christian conceptions of charity and justice; some argued against slavery whilst others, including the influential Thomas Aquinas, argued the case for slavery subject to certain restrictions. By the 11th century when almost all of Europe had been Christianized, the laws of slavery in civil law codes had become antiquated and unenforceable.[citation needed] There were a number of areas where Christians lived with non-Christians; in these locations, canon law permitted Christians to keep non-Christian slaves, as long as these slaves were treated humanely and were freed if they chose to convert to Christianity.[citation needed]

The Church prohibited the export of Christian slaves to non-Christian lands.[167] However, there was an explicit legal justification for the enslavement of Muslims, found in the Decretum Gratiani and later expanded upon by the 14th century jurist Oldradus de Ponte.

By the end of the Medieval period, enslavement of Christians had been largely replaced by serfdom throughout Europe although enslavement of non-Christians remained permissible, and had seen a revival in Spain and Portugal.[168]

Although some Catholic clergy, religious orders and Popes owned slaves, and the naval galleys of the Papal States used captured Muslim galley slaves,[169] Roman Catholic teaching began to turn more strongly against “unjust” forms of slavery, beginning in 1435, prohibiting the enslavement of the recently baptised,[169] and culminating in pronouncements by Pope Paul III in 1537.

Age of Discovery

[edit]When the Age of Discovery greatly increased the number of slaves owned by Christians, the response of the church, under strong political pressures, was confused and ineffective in preventing the establishment of slave societies in the colonies of Catholic countries. Papal bulls such as Dum Diversas, Romanus Pontifex and their derivatives, sanctioned slavery and were used to justify enslavement of natives and the appropriation of their lands during this era.[169][170][171][172]

A number of Popes did issue papal bulls condemning "unjust" enslavement, ("just" enslavement was still accepted), and mistreatment of Native Americans by Spanish and Portuguese colonials; however, these were largely ignored. Nonetheless, Catholic missionaries such as the Jesuits, who also owned slaves, worked to alleviate the suffering of Native American slaves in the New World. Debate about the morality of slavery continued throughout this period, with some books critical of slavery being placed on the Index of Forbidden Books by the Holy Office between 1573-1826.[173]

Spanish missionaries such as Antonio de Montesinos criticized the mistreatment of indigenous peoples by Spanish colonists and missionaries.[174][175] King Ferdinand enacted laws to protect the indigenous peoples, ultimately causing a revolt among the Spanish colonists, and forcing the government to back down and weaken the laws. Some historians blame the Church for not doing enough to liberate the Indians; others point to the Church as the only voice raised on behalf of indigenous peoples.[176]

Modern era

[edit]Some Protestant missionaries of the Great Awakening initially opposed slavery in the South, but by the early decades of the 19th century, many Baptist and Methodist preachers in the South had come to an accommodation with it in order to evangelize the farmers and workers. Disagreements between the newer way of thinking and the old often created schisms within denominations at the time. Differences in views toward slavery resulted in the Baptist and Methodist churches dividing into regional associations by the beginning of the Civil War.[177]

Throughout Europe and the United States, Christians, usually from 'un-institutional' Christian faith movements, not directly connected with traditional state churches, or "non-conformist" believers within established churches, were to be found at the forefront of the abolitionist movements.[178][179] Prominent among Christian abolitionists was Parliamentarian William Wilberforce in England.[180] Methodist founder John Wesley denounced human bondage as "the sum of all villainies," and detailed its abuses.[181] Many evangelical leaders in the United States such as Presbyterian Charles Finney and Theodore Weld, and women such as Harriet Beecher Stoweand Sojourner Truth motivated hearers to support abolition.[182] Abolitionist writings used the Christian scriptures and principle in arguing against the institution of slavery, and in particular the chattel form of it as seen in the South.[183][184][185]

Quakers in particular were early leaders in abolitionism. In the face of strident opposition, many Methodist, Baptist, and Presbyterian members freed their slaves and sponsored black congregations. In 1801, American Methodists made anti-slavery sentiments a condition of church membership.[186]

During this era, Roman Catholic proclamations against slavery also became increasingly vehement including condemnations by Pope Benedict XIV in 1741, Pope Pius VII in 1815 and Pope Pius IX in 1888.[187]

Despite Pope Gregory XVI's condemnation of the slave trade[188] in 1839, some American bishops continued to support slave-holding interests until the abolition of slavery.[165] Some Roman Catholic efforts did oppose slavery. For example, Daniel O'Connell supported the abolition of slavery in the British Empire and in America.

In 1866 The Holy Office of Pope Pius IX affirmed that, subject to certain conditions, it was not against divine law for a slave to be sold, bought or exchanged.[189] In 1888 Pope Leo XIII condemned slavery in the papal encyclical In Plurimis.[190]

In the 20th century, the Catholic Church made the condemnation of slavery more unequivocal. In 1917, the Roman Catholic Church's Canon Law was officially expanded to specify that "selling a human being into slavery or for any other evil purpose" is a crime.[191]

Antisemitism

[edit]Christianity has had a troubled relationship with Judaism that often involved antisemitism. Some charge that Christianity fomented and incited antisemitism which, in turn, was responsible for the Holocaust. While Robert Michael acknowledges that the precise influence of Christianity in bringing about the Holocaust is "impossible to determine" and that Christian churches were not direct actors in it, he asserts that "Christian anti-Semitism is not only the source but also the major ideological basis of Nazi anti-Semitism."[192] This charge is made not only by Jewish sources but by Christian and non-Christian sources as well. For example, Father John Pawlikowski has urged Catholics and others to confront the long history of Christian antisemitism. Pawlikowski argues that the Holocaust must remain a central issue for Christian identity and reflection. According to Pawlikowski, there is "an unwillingness to acknowledge that the Church as an institution played a significant role in the promotion of antisemitism."[193] Some religious scholars have found what they claim are antisemitic passages in the New Testament and the patristic writings, thus arguing that antisemitism has its roots in early Christianity. Some Christian apologists rebut this charge by drawing a distinction between "anti-Judaism" and "anti-semitism" claiming that Christianity has only been anti-Judaic and not anti-semitic. They define anti-Judaism as a disagreement of religiously sincere people with the tenets of Judaism, while regarding antisemitism as an emotional bias or hatred not specifically targeting the religion of Judaism. Under this approach, anti-Judaism is not regarded as antisemitism as it only rejects the religious ideas of Judaism and does not involve actual hostility to the Jewish people.[194]

"The question of the relation of traditional Christian anti-Judaism and modern antisemitism" has "ignite[d] explosive debates" among scholars.[195] Some sources characterize the distinction between anti-Judaism and anti-Semitism as "semantics" and reject the argument as "flawed".[196]

These anti-Judaic and anti-semitic attitudes persisted in Christian preaching, art and popular teaching of contempt for Jews over the centuries.[197] In many Christian countries it led to civil and political discrimination against Jews, legaldisabilities, and in some instances to physical attacks on Jews which in some cases ended in emigration, expulsion, and even death. Some scholars such as Richard Harries argue that, in Western Christianity, anti-Judaism effectively merged into antisemitism by the 12th century.[198]

Throughout Christian history many popes, bishops and some Christian princes stepped up to protect Jews; however, it was only in the mid-20th century that the Catholic Church and many Protestant denominations issued major statements repudiating anti-Judaic theology and began a process of constructive Christian-Jewish interaction[citation needed].

Medieval pogroms

[edit]The pogroms of 1096 were the first major medieval attack by Christians on Jews that is well-documented.[146] In 1348, because of the hysteria surrounding the Black Plague, Jews were massacred in Chillon, Basle, Stuttgart, Ulm,Speyer,Dresden, Strasbourg, and Mainz. By 1351, 60 major and 150 smaller Jewish communities had been destroyed.[199] A large number of the surviving Jews fled to Poland, which was very welcoming to Jews at the time.[200]

Crusades

[edit]Waves of anti-semitic attacks were associated with the preaching of Catholic clerics and religious in support of the launching of Crusades. For example, in the winter of 1095-96, Jews were targeted first in northern France, then in the Rhineland and Bohemia. A fresh wave of persecution against the Jews broke out in northern France and Germany in 1146 as the Second Crusade was being preached. Common features of these waves of antisemitism were demands for vengeance for the alleged deicide committed by the Jews and forced baptisms.[201]

Martin Luther

[edit]

Although the Catholic Church has been criticized for fomenting anti-semitism in pre-Reformation Europe, Protestants have also been targeted for post-Reformation anti-semitism, most notably that espoused by Martin Luther. According to the prevailing view among historians,[202] Luther's anti-Jewish rhetoric contributed significantly to the development of antisemitism in Germany,[203] and in the 1930s and 1940s provided an "ideal underpinning" for the National Socialists' attacks on Jews.[204] Reinhold Lewin writes that "whoever wrote against the Jews for whatever reason believed he had the right to justify himself by triumphantly referring to Luther." According to Michael, just about every anti-Jewish book printed in the Third Reich contained references to and quotations from Luther. Heinrich Himmler wrote admiringly of his writings and sermons on the Jews in 1940.[205]

According to the prevailing view among historians,[202] Martin Luther's anti-Jewish rhetoric contributed significantly to the development of antisemitism in Germany,[203] and in the 1930s and 1940s provided an "ideal underpinning" for the National Socialists' attacks on Jews.[204] Reinhold Lewin writes that "whoever wrote against the Jews for whatever reason believed he had the right to justify himself by triumphantly referring to Luther." According to Michael, just about every anti-Jewish book printed in the Third Reich contained references to and quotations from Luther. Heinrich Himmler wrote admiringly of his writings and sermons on the Jews in 1940.[205]

Franklin Sherman argues that Luther "cannot be distanced completely from modern antisemites." Regarding Luther's treatise, On the Jews and Their Lies, the German philosopher Karl Jaspers wrote: "There you already have the whole Nazi program".[206]

In his Lutheran Quarterly article, Wallmann argued that Luther's anti-semitic writings were largely ignored by antisemites of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Paul Halsall argues that Luther's views had a part in laying the groundwork for the racial European antisemitism of the 19th century. He writes that "although Luther's comments seem to be proto-Nazi, they are better seen as part of tradition [sic] of Medieval Christian anti-semitism. While there is little doubt that Christian anti-semitism laid the social and cultural basis for modern anti-semitism, modern anti-semitism does differ in being based on pseudo-scientific notions of race. The Nazis imprisoned and killed even those ethnic Jews who had converted to Christianity: Luther would have welcomed their conversions."[207]

Russian Empire

[edit]Yuri Tabak describes the history of antisemitism in Russia as having the same forms "already traditional in the West".[208] Tabak describes Christian-Jewish relations in Russia as having "maintained a more or less neutral attitude" during periods of calm but with a "mixture of fear and hatred of Jews characteristic of medieval Christian consciousness" smouldering below the surface. He asserts that social, economic, religious or political changes could bring this undercurrent of antisemitism to the surface, changing the Christian populace into "a fanatical crowd capable of murder and pillage."[208]

A number of sources assert that "a number of influential Orthodox prelates and churchmen fomented antisemitism that led to massive pogroms, although some other ecclesiastical figures spoke out in defense of the Jews."[209] Tabak asserts, however, that "the fundamental difference in the conduct of anti-Jewish measures in Russia (compared to Western Europe), ... lies in the much lesser role played by the Russian Orthodox Church in the conduct of this policy," According to Tabak, it is much harder to find examples of involvement of high-ranking Russian Orthodox leaders in antisemitic policies. He asserts that "(a)ll anti-Jewish decisions were conducted by state administrative organs, acting on the authority of emperors, state committees and ministries." He explains that "(e)ven if the Ecclesiastical Collegium under Peter the Great and, later, the Holy Synod, agreed with and approved certain measures, it is important to remember that these aforementioned institutions were essentially government departments." Thus, he concludes that "(a)lthough it would be entirely natural to suppose that the Church authorities had a particular influence on the State in the conduct of anti-Jewish measures and even that these were indeed initiated by the Church, there is no conclusive evidence to support this "[208]