User:Red Phoenician/Tur Lebnon

The name Tur Lebnon (Syriac: ܛܘܪ ܢܒ݂ܢܢ, Ṭūr Leḇnān, Syriac pronunciation: [tˤur lewˈnɔn], Ṭūr Lewnōn) refers to an autonomous confederation of Maronite principalities in Mount Lebanon from the late-7th century to the early-14th century.

Tur Lebnon | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 676–1382 | |||||||||

|

Flag of Prince Ibrahim | |||||||||

| Motto: Bokh ndaqar lab‘eldvovayn – wmétoul shmokh ndoush lsonayn (Syriac) (English: “Through you, we push back our enemies – and through your name we trample our foes”)[3][4] | |||||||||

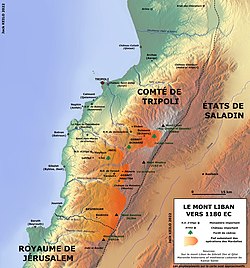

Main Maronite principalities during the Crusader period, circa 1180 A.D. | |||||||||

| Status | Vassal of the Byzantine Empire (676-685) Autonomous confederation (685-1109/1289-1382) Semi-vassal of the County of Tripoli (1109-1289) | ||||||||

| Capital | Baskinta and Byblos | ||||||||

| Common languages | Lebanese Aramaic Syriac (Liturgical and literary)[5][6][7] | ||||||||

| Religion | Maronite Catholicism | ||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Maronite | ||||||||

| Government | Theocratic confederation | ||||||||

| Prince/King | |||||||||

• 694 | Ibrahim | ||||||||

• 759 | Banadar | ||||||||

• c. 1140 | Kisra | ||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||

• Mardaites enter Mount Lebanon | 676 | ||||||||

| 694 | |||||||||

• Muneitra Revolution | 759 | ||||||||

• Maronites establish contact with crusaders | 1098 | ||||||||

| 12 July 1109 | |||||||||

| 1305 | |||||||||

• Martyrdom of Patriarch Gabriel of Hjoula | 1367 | ||||||||

• Mamluk deacon | 1382 | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• c. Late 12th century | 80,000[8] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Lebanon | ||||||||

Originally intended as a buffer state created by the Byzantine Empire against Umayyyad incursions the entity fell out of the favor due to a peace agreement between the Byzantines and Arabs which stipulated the withdrawl of Mardaite troops from the region. This coupled with the election of the Maronite bishop of Batroun, John Maroun, as Patriarch of Antioch without approval of the Byzantine emperor led to a failed invasion by the former suzerain against the inhabitants of Mount Lebanon.

The Maronites then led an uneasy autonomous status from the major powers of the region but were not spared from assaults and raids against their villages. This led to the Maronites to increase further and further within the hinterlands of Mount Lebanon and mainly abandon the coastal cities of Lebanon.

The Maronites remained culturally and religiously isolated until the late-10th century when the Crusaders arrived in the Levant allowing the Maronites to restablish contact with the rest of Christendom and Europe. Under the Crusaders the Maronites prospered and were treated as equals among the Franks however Latinization efforts from the Europeans led to conflicts between the Europeans and Maronites as well as internal divisions among the Maronites themselves. When the Crusaders left the region in defeat many Maronites followed them to Cyprus, Rhodes and Malta.[9]

The Maronites again remained autonomous outside of Islamic domain until the Mamluks finally subjugated them in 1367, allowing them to keep their self-goverance but with the penalty of a tribute. This period was marred with continual persecution which forced the Maronites to retreat even further into the Qadisha Valley where many of them and their Patriarch remained until the mid-19th century.

Etymology[edit]

The name Tur Lebnon is a transliteration of the Syriac name ܛܘܪ ܢܒ݂ܢܢ or ṭūr leḇnān meaning Mount Lebanon with Tur meaning mount in Syriac and Lebnon ultimately deriving from the Semitic root LBN meaning white in reference to the snow capped peaks of the mountain. Other sources refer to the entity as the Marada state, the Maronite nation or simply Maronite Lebanon.[10]

Saint Maron Marada(h) Tur Lebnon The Holy Mountain of God

Background[edit]

Sometime between the late 5th century and early 6th century AD a man by the name of Maron left the urban life of the area near Cyrrhus in order to seek solitude as a Christian hermit. Maron moved to Mount Nabo in the village of Kefar-Nabo, there he converted a pagan temple dedicated to the Assyrian deity Nabu into a Christian church. Maron began to gain popularity for his austerity of life and gift of healing, both in physical and spiritual matters. Many people came to visit Maron seeking his healing or wisdom with many people, both men and women, becoming his disciples. (Dau) (Dib) (Aspects)

Christianization of the Lebanese[edit]

One of Maron's disciples was a man known as Abraham of Cyrrhus. Although Christianity had been spreading along the Phoenician coast since the time of Jesus, as well as due to evangelization efforts notably by Saint Paul and Saint Peter the interior of Mount Lebanon still remained largely pagan. According to Theodoret of Cyrus, when Abraham was made aware that paganism was still prelevant within the Aqoura- Afqa area of Mount Lebanon he went with some companions in order to convert the people. Abraham and his companions entered the town as walnut sellers and rented a house, there Abraham would sing the Divine Office in a low voice. When some of the townspeople discovered this, they held a meeting with the whole town where they decided to get rid of Abraham and his companions. The townspeople assaulted the house that the hermits were staying in, boarded up the doors and windows, and tried to suffocate the hermits by introducing a poisonous powder into the house. However, Abraham and his companions continued chanting their prayers to God among their imminent death. Shocked by this, the townspeople stopped their attack and let the hermits go but only if they would leave the city at once. The hermits begged to stay until the next day but at the same instance the tax collectors of the government arrived. The townspeople could not afford to pay the required taxes and thus began to be harassed by the tax collectors. However, Abraham offered to pay the taxes himself if the tax collectors would leave the townspeople alone. Impressed by this act the townspeople then begged Abraham to stay and become their leader. Thus, this began the Christianization of the central area of Mount Lebanon with Abraham building a church in the town and becoming their priest. Abraham stayed in the town for three years before returning to his ascetic life as a hermit. The Abraham River in Lebanon was named Abraham replacing its previous name the Adonis river after a pagan god venerated in the region.

Around the same time, a group of people from the northern region of Mount Lebanon were being attacked by wild animals who were threatening their lives as well as their livestock. Hearing of the feats of Simeon Stylites, another disciple of Maron, the people traveled to inquire him for advice. Upon receiving the people Simeon Stylites asked if they were Christians to which the people responded that they were not. Simeon Stylites thus instructed them to get baptized and embrace Christianity to which the people agreed. The people then went back to their country accompanied by priests who were disciples of Simeon who baptized them, taught them the Christian religion, and gave them the sacraments. The priests also told the people to erect Crosses on the borders of their country in order to protect them against evil and the wild animals attacking them. Thus, crosses were set up on the hills of places such as Tannourine, Hasroun, Hadshit, Bsharri, Ehden, and other places. (Dau) (One more missing)

Beth Maron[edit]

History[edit]

Early Middle Ages[edit]

Under the Byzantines[edit]

In the year 638, after over a hundred years of Arab raids and invasions, the region of the Levant fell to the Rashidun Caliphate from the hold of the Byzantine Empire. While the interior regions were easily subjugated under Islamic rule the Levantine coastline and mountain areas proved more difficult due to both their zealous Christian populations as well as a terrain disadvantage with the Byzantines easily being able to send ships from the sea and the rugged terrain of the mountains. The situation only became more difficult for the Arabs when in 676 Mardaites began to descend from the Nur Mountains and reclaim much of the coastal Levant threatening the Rashidun presence.

Theophanes the Confessor recounted this event in his Chronicle:

In this year [676] the Mardaites entered the Lebanon range and made themselves masters from the Black Mountain as far as the Holy City and captured the peaks of Lebanon. Many slaves, captives, and natives took refuge with them, so that in a short time they grew to many thousands. When Mauias and his advisers had learnt of this, they were much afraid, realizing that the Roman Empire was guarded by God. So he sent ambassadors to the emperor Constantine, asking for peace and promising to pay yearly tribute to the emperor.[11]

Battle of Amioun[edit]

Relations with the Arabs[edit]

Umayyad interactions[edit]

Mardaite revolts[edit]

Thou hast heard of the expulsion of the dhimmis from Mt. Lebanon, although they did not side with those who rebelled, and of whom many were killed by thee and the rest returned to their villages. How didst thou then punish the many for the fault of the few and make them leave their homes and possessions in spite of Allah's decree: 'Nor shall any sinning one bear the burden of another,' which is the most rightful thing to abide by and follow! The command worthy of the strictest observance and obedience is that of the Prophet who says, 'If one oppresses a man bound to us by covenant and charges him with more than he can do, I am the one to overcome him by arguments.'[12]

High Middle Ages[edit]

Arrival of the Crusaders[edit]

In the year 1096, Pope Urban II convened the Council of Clermont which became the catalyst for the First Crusade. In 1099, as the Crusaders were traveling down the Levantine coastline they first came into contact with the Maronites in the city of Arqa (the capital of Akkar at the time). The Crusaders were surprised by the presence of the Maronites as they had thought all Christians had been wiped out from the region under the reign of Islam. The Maronites however openly welcomed the Crusaders as Christian brothers and an alliance between the two parties was formed.[13]

The condition of the Maronites at this time was described by Raymond of Aguilers:

But when the Saracens and Turks arose through the judgment of God, those Surians were in such great oppression for four hundred and more years that many of them were forced to abandon their fatherland and the Christian law. If, however, any of them through the grace of God refused, they were compelled to give up their beautiful children to be circumcised, or converted to Mohammedanism; or they were snatched from the lap of their mothers, after the father had been killed and the mother mocked. Forsooth, that race of men were inflamed to such malice that they overturned the churches of God and His saints, or destroyed the images; and they tore out the eyes of those images which, for lack of time, they could not destroy, and shot them with arrows; all the altars, too, they undermined. Moreover, they made mosques of the great churches. But if any of those distressed Christians wished to have an image God or any saint at his home, he either redeemed it month by month, or, year by year, or it was thrown down into the dirt and broken be, fore his eyes. In addition, too harsh to relate, they placed youths in brothels, and, to do yet more vilely, exchanged their sisters for wine. And their mothers dared not weep openly at these or other sorrows.[14]

The Crusaders inquired the Maronites about which route to take on the way to Jerusalem to which the Maronites presented three options: The Damascus route, on which food was plentiful but water was scarce, the route by way of the mountain, on which food and water were plentiful but which was difficult for the beasts of burden, and the coastal route, on which the Franks might encounter opposition from the local Moslem population.[15] The Crusaders ultimately decided that the coastal route was the best option and continued towards Jerusalem. (BOOK OF THOMAS)

From this point onwards an alliance between the Maronites and Crusaders began with the Crusaders speaking favorably of their newfound Christian brethern.

Jacques de Vitry described the Maronites as experienced archers who were swift and skilful in battle[16] and William of Tyre wrote of them as a stalwart race, valiant fighters, and of great service to the Christians in the difficult engagements which they so frequently had with the enemy.[17]

The Maronites assisted the Crusaders again in the years 1102 during the Siege of Tripoli and in 1111 at the Battle of Shaizar. At this point the Maronite principalities had been de jure under the County of Tripoli since at least 1109 but were still de jure independent as the Crusaders did not force any demands or tribute upon them.

At the same time, some of the Maronites still had cordial relations with the Arabs and often interacted with them in regards to commerce and politics. One such account of this is described by the Arab knight and poet Usama ibn Munqidh in his autobiography Kitab al-I'tibar in regards to the two sick persons under a Maronite lords rule.

The lord of al-Munaytirah wrote to my uncle asking him to dispatch a physician to treat certain sick persons among his people. My uncle sent him a Christian physician named Thabit. Thabit was absent but ten days when be returned. So we said to him, "How quickly has thou healed thy patients!" He said:

They brought before me a knight in whose leg an abscess had grown; and a woman afflicted with imbecility. To the knight I applied a small poultice until the abscess opened and became well; and the woman I put on diet and made her humor wet. Then a Frankish physician came to them and said, "This man knows nothing about treating them." He then said to the knight, "Which wouldst thou prefer, living with one leg or dying with two?" The latter replied, "Living with one leg." The physician said, "Bring me a strong knight and a sharp ax." A knight came with the ax. And I was standing by. Then the physician laid the leg of the patient on a block of wood and bade the knight strike his leg with the ax and chop it off at one blow. Accordingly he struck it-while I was looking on-one blow, but the leg was not severed. He dealt another blow, upon which the marrow of the leg flowed out and the patient died on the spot. He then examined the woman and said, "This is a woman in whose head there is a devil which has possessed her. Shave off her hair." Accordingly they shaved it off and the woman began once more to cat their ordinary diet-garlic and mustard. Her imbecility took a turn for the worse. The physician then said, "The devil has penetrated through her head." He therefore took a razor, made a deep cruciform incision on it, peeled off the skin at the middle of the incision until the bone of the skull was exposed and rubbed it with salt. The woman also expired instantly. Thereupon I asked them whether my services were needed any longer, and when they replied in the negative I returned home, having learned of their medicine what I knew not before.[18]

One notorious incident occured when the people of Bsharre, who were unhappy with the Crusaders encroachment on their region allied with

Despite these problems the Maronites and Crusaders overall had good relations to the point where Saint King Louis IX of France was recieved by a delegation of 25,000 Maronites who offered him supplies and gifts and to which he in return proclaimed in a letter written on the 21st of May, 1250 to the emir, Patriarch, and bishops of the Maronites that: We are persuaded that this nation, which we find established under the name of Saint Maron, is a part of the French nation, because its friendship for the French resembles the friendship that the French bear among themselves. Consequently, it is right that you and all the Maronites should enjoy the same protection which the French enjoy near us, and that you should be admitted to the employments as they themselves are.[19]

Economy[edit]

The Maronite economy was heavily connected with the Byzantines until relations between the two deteriorated. After relations had been repatched interactions along the coastline were frequent until the Abbasid occupation of Lebanon’s coast isolating the Maronites to the mountains culturally and economically. Stranded without any contact with the outside world the Maronites were forced to cultivate the lands they were surrounded by. Transforming the hard and rocky terrain into farmable soil the Maronites turned Mount Lebanon into a fertile region abundant with plant life and vegetation. When the Mamluks took over the region the Maronites had access to trade with both the city dwelling Arabs and Europeans arriving from sea. Mount Lebanon gained a reputation for its abundance in medicinal herbs, wood used for making utensils, and vineyards and plantations full of olives and figs and other fruits and plants. The economy again declined during the European age of exploration which allowed European merchants to circumvent the ports of the Muslim ruled Mediterranean and directly trade with Asia. This would directly affect the Lebanese ports and economy which would not rebound until later years under the Ottomans and Lebanese independence.

List of principalities[edit]

This list is incomplete; you can help by adding missing items. |

- Principality of Aqoura under the Al-Chemor dynasty (1211-1633)

- Principality of Bsharri under the Ayyub dynasty (1382-1547)

- Principality of Zawyie under the Al-Chemor dynasty (1641-1747)

List of princes[edit]

322

This list covers the chronology of the princes of the three main cities of Byblos, Baskinta and Banias.

|

1. Princes of Byblos

|

2. Princes of Baskinta

|

3. Princes of Banias

|

- Yusif of Byblos, Kesra of Kesrawan, Ayub (Job) of Banias and Jerusalem, Elias, Yusif, and Hanna (c. 628-675)

- Ya'qub (675-695)

- Abraham, nephew of John Maron (695-728)

- Butros (728-756)

- Musa (756-790)

- George and Yuhanna (790-890)

- Hanna, Andrawos, and Musa (890-1020)

- 'Assaf (1020-1050)

- George (1050-1090)

- Musa and Butros (1090-1190)

- Bachos and Ya'qub (1190-1215)

- Sham'un (1215-1239)

- Ya'qub (1239-1296)

- Estephan (1296-1352)

Legacy[edit]

Political thought [20] rebel, petit liban, east beirut

See also[edit]

| History of Lebanon |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Maronite Church |

|---|

|

| Patriarchate |

| Religious orders and societies |

| Communities |

| Languages |

| History |

| Related politics |

|

|

References[edit]

- ^ Moukarzel, Joseph (January 2007). Gabriel Ibn al-Qilāʻī, ca 1516: approche biographique et étude du corpus. PUSEK. p. 420.

- ^ Moukarzel, Joseph (January 2015). Christian-Muslim Relations. A Bibliographical History. Volume 7 Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa and South America (1500-1600). Brill. p. 553.

- ^ Iskandar, Amine (2008). Epigraphie Syriaque au Liban – vol 1. Louayzé, Lebanon: NDU Press.

- ^ Iskandar, Amine (12 April 2021). "Syriac Identity of Lebanon part 15: Syriac Maronite Squarish and Cross Epigraphs". syriacpress.com. Syriacpress.

- ^ Hitti, Philip (1957). Lebanon in History. India: Macmillan and Co Ltd. p. 257.

- ^ Hitti, Philip (1957). Lebanon in History. India: Macmillan and Co Ltd. p. 336.

- ^ Schulze, Kirsten E; Stokes, Martin; Campell, Colm (1996). Nationalism, Minorities and Diasporas: Identities and Rights in the Middle East. Magee College: Tauris Academic Studies. p. 162.

This identity was underlined by Christian resistance to adopting Arabic as the spoken language. Originally they had spoken Syriac but increasingly opted to use "Christian" languages such as Latin, Italian, and most importantly, French.

- ^ Dib, Pierre (1962). History of the Maronite Church (PDF). Beirut, Lebanon: Imprimerie Catholique. p. 58.

- ^ Ristelhueber, René (1915). "Les Maronites". Revue des Deux Mondes. 25 (6): 187–215.

- ^ Schulze, Kirsten E; Stokes, Martin; Campell, Colm (1996). Nationalism, Minorities and Diasporas: Identities and Rights in the Middle East. Magee College: Tauris Academic Studies. p. 161.

The Maronite fear of Islam dates back to 676-7 when Lebanon's Christians, mainly Maronites, formed the Mardaite states in the Lebanese mountains in rebellion to Islam and the Arabs.

- ^ The Confessor, Theophanes (1997). The Chronicle Of Theophanes Confessor. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 496.

- ^ Hitti, Philip (1916). The origins of the Islamic state. Beirut, Lebanon: Columbia University. p. 251.

- ^ El-Hayek, Elias. Struggle for Survival: The Maronites of the Middle Ages. Diocese of St. Maro.

- ^ Krey, August C. (1921). The First Crusade: The Accounts of Eyewitnesses and Participants. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 243.

- ^ Salibi, Kamal (1959). Maronite Historians of Medieval Lebanon. Beirut, Lebanon: American University of Beirut.

- ^ de Vitry, Jacques (1896). The History of Jerusalem A.D. 1180. Pennsylvania State University.

- ^ of Tyre, William (1943). A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea. New York, New York: Internet Archive.

- ^ ibn Munqidh, Usmah. "Medieval Sourcebook: Usmah Ibn Munqidh (1095-1188): Autobiography, excerpts on the Franks". sourcebooks.fordham.edu.

- ^ Hitti, Philip (1957). Lebanon in History. India: Macmillan and Co Ltd. p. 321.

- ^ Zogheib, Penelope (December 2013). Lebanese Christian nationalism : a theoretical analyses of a national movement. Boston, MA: Northeastern University. p. 61-62.

Bibliography[edit]

- Isṭifān, Duwayhī (1890). Tārīkh al-ṭāʾifah al-Mārūnīyah. Princeton University.

- al-Shidyaq, Tannus (1859). أخبار الاعيان في جبل لبنان. Beirut, Lebanon: Lebanese University.

- Dib, Pierre (1962). History of the Maronite Church (PDF). Beirut, Lebanon: Imprimerie Catholique.

- Moukarzel, Joseph (January 2007). Gabriel Ibn al-Qilāʻī, ca 1516: approche biographique et étude du corpus. Bibliothèque de l’Université Saint-Esprit de Kaslik.

- Boulos, Jawad (1973). Lebanon And Neighboring Countries. Beirut, Lebanon: Badran and Partners Press.

- Makki, Muhammad Ali (January 2006). Lebanon From The Arab Conquest To The Ottoman Conquest. Beirut, Lebanon: An-Nahar Publishing House. ISBN 9953-74-087-9.

- El-Hayek, Elias. Struggle for Survival: The Maronites of the Middle Ages. Diocese of St. Maro.

- Sandrussi, Michael (2017). The Origins of the Maronites: People, Church, Doctrine. Academia.edu.

- The Confessor, Theophanes (1997). The Chronicle Of Theophanes Confessor. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Hitti, Philip (1916). The origins of the Islamic state. Beirut, Lebanon: Columbia University.

- of Aguilers, Raymond (1098–1105). Historia Francorum qui ceperunt Iherusalem. New York, New York: Fordham University.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - of Tyre, William (1943). A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea. New York, New York: Internet Archive.

- de Vitry, Jacques (1896). The History of Jerusalem A. D. 1180. Pennsylvania State University.

- Hitti, Philip (1957). Lebanon in History. India: Macmillan and Co Ltd.

- Mourani, César (2007). L'Architecture Religieuse de Cobiath sous les Croisés. Kobayat: Elie Abboud.

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Maronite-church