User:Remsense/巫

Appearance

.

.

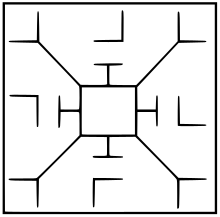

Shang-dynasty graphemes signifying the power of ordering

❶ k:巫 wū — "shaman", "man who knows", the cross potent ☩ being a symbol of the magi and magic/craft also in Western cultures;[15]

❷ k:方 fāng — "square", "phase", "direction", "power" and other meanings of ordering, which was used interchangeably with the grapheme wu;

❸ k:矩 jǔ — "carpenter's square";

❹ k:央 yāng — "centering".

All of them contain the rod element signifying the square tool, used to make right angles. According to David W. Pankenier, the same staff is the horizontal line in the grapheme 帝 dì, "deity" or "emperor".[16]

❷ k:方 fāng — "square", "phase", "direction", "power" and other meanings of ordering, which was used interchangeably with the grapheme wu;

❸ k:矩 jǔ — "carpenter's square";

❹ k:央 yāng — "centering".

All of them contain the rod element signifying the square tool, used to make right angles. According to David W. Pankenier, the same staff is the horizontal line in the grapheme 帝 dì, "deity" or "emperor".[16]

Shang and Zhou graphemes for Di and Tian

❶ One version of the Shang grapheme for the nominal Dì k:帝 ("Deity", "deities", "divinity"), which according to David W. Pankenier was drawn by connecting the stars of the "handle" of Ursa Major and the "scoop" of Ursa Minor determining the northern culmen (北极 Běijí).[21] Otherwise, according to John C. Didier this and all the other graphemes ultimately represent Dīng 口 (archaic of k:丁, which also signifies the square tool), the north celestial pole godhead as a square.[22] The bar on top, which is either present or not and one or two in Shang script, is the k:上 shàng to signify "highest".[23] The crossbar element in the middle represents a carpenter's square, and is present in other graphemes including 方 fāng, itself meaning "square", "direction", "phase", "way" and "power", which in Shang versions was alternately represented as a cross potent ☩, homographically to 巫 wū ("shaman").[16] Dì is equivalent to symbols like wàn 卍 ("all things")[1] and Mesopotamian 𒀭 Dingir/An ("Heaven").[2]

❷ Another version of the Shang grapheme for the nominal Dì.[24]

❸ One version of the Shang grapheme for the verbal dì k:禘, "to divine, to sacrifice (by fire)". The modern standard version is distinguished by the prefixion of the signifier for "cult" (礻shì) to the nominal Dì.[25][26] It may represent a fish entering the square of the north celestial pole (Dīng 口),[27] or rather k:定 dìng, i.e. the Square of Pegasus or Celestial Temple, when aligning with Dì and thus framing true north.[28] Also dǐng k:鼎 ("cauldron", "thurible") may have derived from the verbal dì.[29]

❹ Shang grapheme for Shàngjiǎ k:上甲, "Supreme Ancestor", an alternate name of Shangdi.[30]

❺ The most common Zhou version of the grapheme Tiān ("Heaven") k:天, represented as a man with a squared (dīng 口) head.[31]

❻ Another Zhou version of the grapheme for Tiān.[31]

❷ Another version of the Shang grapheme for the nominal Dì.[24]

❸ One version of the Shang grapheme for the verbal dì k:禘, "to divine, to sacrifice (by fire)". The modern standard version is distinguished by the prefixion of the signifier for "cult" (礻shì) to the nominal Dì.[25][26] It may represent a fish entering the square of the north celestial pole (Dīng 口),[27] or rather k:定 dìng, i.e. the Square of Pegasus or Celestial Temple, when aligning with Dì and thus framing true north.[28] Also dǐng k:鼎 ("cauldron", "thurible") may have derived from the verbal dì.[29]

❹ Shang grapheme for Shàngjiǎ k:上甲, "Supreme Ancestor", an alternate name of Shangdi.[30]

❺ The most common Zhou version of the grapheme Tiān ("Heaven") k:天, represented as a man with a squared (dīng 口) head.[31]

❻ Another Zhou version of the grapheme for Tiān.[31]

Olden versions of the grapheme 黄 huáng, "yellow"

❶ Shang oracle bone script;

❷ Western Zhou bronzeware script;

❸ Han Shuowen Jiezi;

❹ Yuan Liushutong.

According to Qiu Xigui, the character "yellow" signifies the power of the 巫 wū ("shaman").[32]: 12, note 33 The Yellow God is the north celestial pole, or the pole star, and it is "the spirit father and astral double of the Yellow Emperor".[32]: 42, note 25

❷ Western Zhou bronzeware script;

❸ Han Shuowen Jiezi;

❹ Yuan Liushutong.

According to Qiu Xigui, the character "yellow" signifies the power of the 巫 wū ("shaman").[32]: 12, note 33 The Yellow God is the north celestial pole, or the pole star, and it is "the spirit father and astral double of the Yellow Emperor".[32]: 42, note 25

- ^ a b Didier (2009), p. 256, Vol. III.

- ^ a b Mair, Victor H. (2011). "Religious Formations and Intercultural Contacts in Early China". In Krech, Volkhard; Steinicke, Marion (eds.). Dynamics in the History of Religions between Asia and Europe: Encounters, Notions, and Comparative Perspectives. Leiden: Brill. pp. 85–110. ISBN 978-9004225350. pp. 97–98, note 26.

- ^ Didier (2009), p. 257, Vol. I.

- ^ Didier (2009), passim.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Reiterwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Milburnwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Assasi, Reza (2013). "Swastika: The Forgotten Constellation Representing the Chariot of Mithras". Anthropological Notebooks (Supplement: Šprajc, Ivan; Pehani, Peter, eds. Ancient Cosmologies and Modern Prophets: Proceedings of the 20th Conference of the European Society for Astronomy in Culture). XIX (2). Ljubljana: Slovene Anthropological Society. ISSN 1408-032X.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Cheu1988was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

DeBernardi2007was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Pankenier (2013), p. 55.

- ^ Zhong (2014), pp. 196, 202.

- ^ Zhong (2014), p. 222.

- ^ Didier (2009), p. 128.

- ^ Maeder, Stefan (2011), "The Big Dipper, Sword, Snake and Turtle: Four Constellations as Indicators of the Ecliptic Pole in Ancient China?", in Nakamura, Tsuko; Orchiston, Wayne; Sôma, Mitsuru; Strom, Richard (eds.), Mapping the Oriental Sky. Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Oriental Astronomy, Tokyo: National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, pp. 57–63.

- ^ Mair, Victor (2012). "The Earliest Identifiable Written Chinese Character". In Huld, Martin E.; Jones-Bley, Karlene; Miller, Dean A. (eds.). Archaeology and Language: Indo-European Studies Presented to James P. Mallory. Institute for the Study of Man. pp. 265–279. ISBN 978-0984538355. ISSN 0895-7258.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ a b Pankenier (2013), pp. 112–113.

- ^ Didier (2009), p. 137 ff, Vol. III.

- ^ Pankenier (2004), pp. 226–236.

- ^ Didier (2009), p. 111, Vol. II.

- ^ Didier (2009), p. 216, Vol. I.

- ^ Pankenier (2013), pp. 103–105.

- ^ Didier (2009), p. 118, Vol. II and passim.

- ^ Didier (2009), p. 133, Vol. II.

- ^ Didier (2009), p. 100, Vol. II.

- ^ Didier (2009), p. 107 ff, Vol. II.

- ^ Pankenier (2013), p. 103.

- ^ Didier (2009), p. 6, Vol. III.

- ^ Pankenier (2013), pp. 138–148, "Chapter 4: Bringing Heaven Down to Earth".

- ^ Pankenier (2013), pp. 136–142.

- ^ Didier (2009), pp. 227–228, Vol. II.

- ^ a b Didier (2009), pp. 3–4, Vol. III.

- ^ a b Wells, Marnix (2014). The Pheasant Cap Master and the End of History: Linking Religion to Philosophy in Early China. Three Pines Press. ISBN 978-1931483261.

- ^ Sun & Kistemaker (1997), p. 121.

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).