User:Rlandmann/Temp

| H-4 Hercules | |

|---|---|

| |

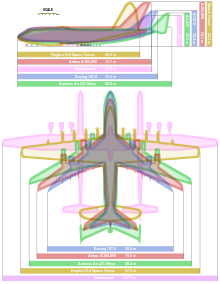

| Spruce Goose. But this is an example of a really really long caption - how does this look? | |

| Role | Very heavy transport, flying boat |

| Manufacturer | Hughes Aircraft |

| Designer | Howard Hughes (Glenn E. Odekirk) Henry J. Kaiser (concept only)[1] |

| First flight | 2 November 1947 |

| Retired | 2 November 1947, stored until 5 April 1976 |

| Status | Project cancelled |

| Produced | Prototype only |

| Number built | 1 |

| Specifications (imaginary!) | |

| Data from [2] | |

| General characteristics | |

| Crew | 1 |

| Capacity | up to 7 passengers |

| Length | 36 ft 4½ in (11.09 m) |

| Span | 44 ft 1½ in (13.45 m) spread, 15 ft 0 in (5.00 m) swept |

| Diameter | 80 ft 0 in (25.00 m) |

| Main rotor diameter | 2 × 32 ft 10 in (10 m) |

| 4 × 32 ft 10 in (10 m) | |

| Width | 100 ft 0 in (30.00 m) |

| Height | 11 ft 5½ in (3.49 m) |

| Wing area | 225.80 ft² (20.98 m²) spread, 220 ft² (20.0 ft²) swept |

| Main rotor area | 25,000 ft² (2,500 m²) |

| Volume | 300,000,000 ft³ (9,000,000 m³) |

| Aspect ratio | 16 |

| Empty weight | 4365 lb (1976 kg) |

| Gross weight | 6075 lb (2062 kg) |

| Useful lift | 16,000 lb (8,000 kg) |

| Powerplant | 2 × Continental TSIO-520-NB flat-six turbocharged piston, of 310 hp (231 kW) each |

| 1 × Junkers Jumo 004 with afterburner , of 2,000 lbf (9.0 kN) thrust dry, 4,000 lbf (18.0 kN) with afterburner | |

| Performance | |

| Maximum speed | 271 mph (436 km/h) |

| Maximum speed | Mach 1.1 |

| Cruising speed | 250 mph (400 km/h) |

| Range | 1528 miles (2459 km) |

| Endurance | 23 min |

| Service ceiling | 30,800 ft (9390 m) |

| Maximum glide ratio | 40 |

| Rate of climb | 1,000 ft/min (5.0 m/s) |

| Rate of sink | 200 ft/min (1.0 m/s) |

| Armament | |

| • guns | |

| • bombs | |

| • torpedoes | |

| • depth charges | |

| • mines | |

| • rocks | |

| Career | |

| Other name(s) | "Spruce Goose" (nickname) |

| Registration | NX37602 |

| Flights | 1 |

| Preserved at | Evergreen Aviation Museum |

The Hughes H-4 Hercules (registration NX37602) is a "one-off" heavy transport aircraft designed and built by the Hughes Aircraft company. The aircraft made its first and only flight on 2 November 1947. Built from wood due to wartime raw material restrictions on the use of aluminium, it was nicknamed the "Spruce Goose" by its critics, some of whom accused Howard Hughes of misusing government funding to build the aircraft. The Hercules is the largest flying boat ever built, and has the largest wingspan and height of any aircraft in history. It survives in good condition at the Evergreen Aviation Museum in McMinnville, Oregon.

Due to wartime restrictions on the availability of metals, the H-4 was built almost entirely of laminated birch, not spruce as its nickname suggests. The Duramold process,[3] a form of composite technology, was used in the laminated wood construction. The aircraft was considered a technological tour de force. It married a soon-to-be outdated technology, flying boats, to a massive airframe that required some truly ingenious engineering innovations to function. Ultimately, however, due to delays and cost overruns, the project was cancelled.

Design and development

[edit]

In 1942, the U.S. Department of War was faced with the need to transport war materiel and personnel to Britain. Allied shipping in the Atlantic Ocean was suffering heavy losses to German U-boats, so a requirement was issued for an aircraft that could cross the Atlantic with a large payload.

The aircraft was the brainchild of Henry J. Kaiser, who directed the Liberty ships program. He teamed with aircraft designer Howard Hughes to create what would become the largest aircraft built or even seriously contemplated at that time. When completed, it was capable of carrying 750 fully-equipped troops or one M4 Sherman tank.[4] The original designation "HK-1" reflected the Hughes and Kaiser collaboration.[5]

The HK-1 contract in 1942, issued as a development contract,[6] initially called for three aircraft to be constructed under a two-year deadline in order to be available for the war effort.[7] Seven different configurations were considered including twin-hulled and single-hulled designs with combinations of four, six and eight, wing-mounted engines.[8] The final design chosen was a behemoth, eclipsing any large transport yet built or even envisioned.[1][6] To conserve metal, it would be built mostly of wood (elevators and rudder were fabric covered[9]); hence, the "Spruce Goose" moniker tagged on the aircraft by the media. It was also referred to as the Flying Lumberyard by critics who believed an aircraft of its size physically could not fly. Hughes himself detested the nickname "Spruce Goose".

While Kaiser had originated the "flying cargo ship" concept, he did not have an aeronautical background and deferred to Hughes and his designer, Glenn E. Odekirk.[1] Development dragged on which frustrated Kaiser who blamed delays partly on restrictions placed for the acquisition of strategic materials such as aluminium but also placed part of the blame on Hughes' insistence on "perfection."[10] Although construction of the first HK-1 had taken place 16 months after the receipt of the development contract, Kaiser withdrew from the project.[11]

Hughes continued the program on his own under the designation "H-4 Hercules" (initially identified as the HFB-1 to signify Hughes Flying Boat First Design[9]), signing a new government contract that now limited production to one example. Work proceeded at a slow pace with the end result that the H-4 was not completed until well after the war was over. There were many reasons for this, not least of which was Hughes' mental breakdown during development.

In 1947, Howard Hughes was called to testify before the Senate War Investigating Committee over the usage of government funds for the aircraft, as Congress was eliminating war-era spending to free up federal funds for domestic projects. Even though he encountered skepticism and even hostility from the committee, Hughes remained unruffled.

In a transcript of a Senate hearing, Hughes said:

| “ | The Hercules was a monumental undertaking. It is the largest aircraft ever built. It is over five stories tall with a wingspan longer than a football field. That's more than a city block. Now, I put the sweat of my life into this thing. I have my reputation all rolled up in it and I have stated several times that if it's a failure I'll probably leave this country and never come back. And I mean it. | ” |

Maiden flight

[edit]During a break in the Senate hearings, Hughes returned to California, ostensibly to run taxi tests on the H-4.[9] On 2 November 1947, a series of taxi tests was begun with Hughes at the controls. His crew included Dave Grant as co-pilot, and a crew of two flight engineers, 16 mechanics and two other flight crew. In addition, the H-4 carried seven invited guests from the press corps plus an additional seven industry representatives, for a total of 32 on board. [12]

After the first two uneventful taxi runs, four reporters left to file stories but the remaining press stayed for the final test run of the day. [13] After picking up speed on the channel facing Cabrillo Beach near Long Beach, the Hercules lifted off, remaining airborne 70 feet (21 m) off the water at a speed of 135 mph (217 km/h or 117 knots) for just under a mile (1.6 km).[14] At this altitude, the aircraft was still experiencing ground effect and some critics believe it lacked the power necessary to climb above ground effect.[15]

Hughes had answered his critics, but the justification for continued spending on the project was gone. Congress ended the Hercules project, and the aircraft never flew again. It was carefully maintained in flying condition until Hughes' death in 1976.

Postwar

[edit]

After years of storage, in 1980, the Hercules was acquired by the California Aero Club, who successfully put the aircraft on display in a large dome adjacent to the Queen Mary exhibit in Long Beach, California. In 1988, The Walt Disney Company acquired both attractions. Disappointed by the lackluster revenue the Hercules exhibit generated, Disney informed the California Aero club that they no longer wished to display the Hercules. After a long search for a suitable host, the California Aero Club awarded custody of the Hughes Flying Boat to Evergreen Aviation Museum. On 9 July 1990, under the direction of museum staff, the aircraft was disassembled and moved by barge to its current home in McMinnville, Oregon (about an hour southwest of Portland) where it has been on display since.

By the mid-1990s, Hollywood converted the former Hughes Aircraft hangars, including the one that held the Hercules, into sound stages. Scenes from movies such as Titanic, What Women Want, and End of Days have been filmed in the 315,000 square foot (29,000 m²) aircraft hangar where Howard Hughes created the legendary flying boat. The hangar will be preserved as a structure eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Buildings in what is today the housing development Playa Vista, Los Angeles, California.

Although the project was a failure, the H-4 Hercules, in some senses, presaged the massive transport aircraft of the late 20th century, such as the Lockheed C-5 Galaxy, the Antonov An-124 and the An-225. The Hercules demonstrated that the physical and aerodynamic principles which make flight possible are not limited by the size of the aircraft, even if the viability of the aircraft itself is, mainly due to the lack (at that time) of powerful enough engines.

Popular culture

[edit]In the film The Rocketeer (1991), hero Cliff Secord uses a large-scale model of the Spruce Goose to escape some eager federal agents and Howard Hughes himself. After Secord glides the model to safety, Hughes expresses astonishment that the craft might actually fly. [16]

The construction and flight of the Hercules was featured in the 2004 Hughes biopic The Aviator. Motion control and remote control models, as well as partial interiors and exteriors, of the aircraft were reproduced for this scene. The motion-control Hercules is on display at the Evergreen Aviation Museum, next to the real Hercules.

The aircraft's hold on popular imagination is demonstrated by the 1987 Hanna-Barbera animated film Yogi Bear and the Magical Flight of the Spruce Goose.[citation needed]

Specifications (H-4)

[edit]Performance specifications are projected. General characteristics

- Crew: 3

Performance

- Power/mass: ( )

See also

[edit]- Akaflieg Köln LS11

- Centrair C101 Pegase

- DFS Habicht

- DG Flugzeugbau DG-800

- DG Flugzeugbau LS10

- Eiri-Avion PIK-20

- Eta Aircraft eta

- Glider Competition Classes

- Fournier RF-5

- Glaser-Dirks DG-100

- Glaser-Dirks DG-200

- Glaser-Dirks DG-300

- Glaser-Dirks DG-400

- Glasflügel

- Glasflügel 303

- Glasflügel 304

- Glasflügel H-101

- Glasflügel H-201

- Glasflügel H-301

- Glasflügel H201

- LET L-13

- Letov LF-107 Luňák

- Letov XLF-207 Laminar

- List of gliders

- MDM / Edward Margañski

- PZL Bielsko Jantar

- PZL Bielsko Jantar Standard

- PZL Bielsko SZD-30

- PZL Bielsko SZD-37

- PZL Bielsko SZD-41

- PZL Bielsko SZD-50

- Pilatus PC-11

- Politechnika Warszawska PW-5

- Politechnika Warszawska PW-6

- Preiss RHJ-7

- Preiss RHJ-8

- Preiss RHJ-9

- Rolladen-Schneider Flugzeugbau

- Rolladen-Schneider LS1

- Rolladen-Schneider LS2

- Rolladen-Schneider LS3

- Rolladen-Schneider LS4

- Rolladen-Schneider LS5

- Rolladen-Schneider LS6

- Rolladen-Schneider LS7

- Rolladen-Schneider LS8

- Rolladen-Schneider LS9

- Rolladen-Schneider LSD Ornith

- Schempp-Hirth Cirrus

- Schempp-Hirth Discus

- Schempp-Hirth Discus-2

- Schempp-Hirth Duo Discus

- Schempp-Hirth Janus

- Schempp-Hirth Nimbus

- Schempp-Hirth Nimbus-2

- Schempp-Hirth Nimbus-3

- Schempp-Hirth Standard Cirrus

- Schempp-Hirth Ventus

- Schempp-Hirth Ventus-2

- Schleicher ASH 25

- Schleicher ASK 13

- Schleicher ASW 12

- Schleicher ASW 15

- Schleicher ASW 19

- Schleicher ASW 20

- Schleicher ASW 24

- Schleicher ASW 27

- Schleicher ASW 28

- Schleicher Ka 7

- Schleicher Ka 8

- Schneider ES-65

- Schreder HP-14

- Schreder HP-15

- Schreder HP-18

- Vogt Lo-100

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c McDonald 1981, p. 40. Note: A misconception exists regarding the H-4 design; Howard Hughes oversaw the design effort, but aircraft engineer Glenn E. Odekirk actually was the designer while Henry J. Kaiser provided an initial concept only. Cite error: The named reference "McDonald p. 40" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Orbis 1985, page 1119

- ^ Winchester 2005, p. 113. Note: The Hughes Corporation had developed the duramold process which laminated plywood and resin into a lightweight but strong building material that could be shaped.

- ^ McDonald 1981, p. 41.

- ^ Odekirk 1982, p. II.

- ^ a b McDonald 1981, p. 45.

- ^ Odekirk 1982, p. 1V.

- ^ McDonald 1981, p. 41-44.

- ^ a b c Winchester 2005, p. 113.

- ^ McDonald 1981, p. 56.

- ^ McDonald 1981, p. 58-59.

- ^ McDonald 1981, p. 78–79.

- ^ McDonald 1981, p. 85–87.

- ^ Francillon 1990, p. 100, 102.

- ^ Wing In Ground effect aerodynamics

- ^ David 1991

Bibliography

[edit]- Hartmann, Gérard (2006), "Les Nieuport de la guerre" (PDF), La Coupe Schneider et hydravions anciens/Dossiers historiques hydravions et moteurs, retrieved 2008-11-07

- Morse, Stan (ed.), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Aircraft, London: Orbis Publishing

{{citation}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Sanger, Ray (2002), Nieuport Aircraft of World War One, Ramsbury: Crowood

- Taylor, Michael J. H. (1989), Jane's Encyclopedia of Aviation, London: Studio Editions

External links

[edit]- Evergreen Aviation Museum, McMinnville, Oregon, home of the plane

- Spruce Goose: Where Is It Now? A history of the plane following Hughes' death

- The Aviator (2004) Biography/drama movie about Howard Hughes with H-4 Hercules Spruce Goose episode

General characteristics Performance Related development something