User:Sechinsic/sketch1

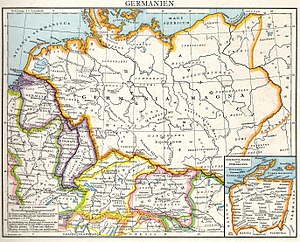

Germania /dʒɜːrˈmeɪniə/ Latin: [ɡɛrˈmaːnɪ.a], originally an expression in ancient Rome for the wide expanses inhabited by Germani. In the art of cartography - and generally in terms of geography - the comprehension of the ancient place-name has remained, whereas even today rests a dispute on what exactly defines the ethnography of Germania. Magna Germania, often just Germania, extended to the north of the Rhine eastward to the Vistula river, and from the springs of the Danube and Main rivers east towards the Carpathian Basin.[1] The place-name Germania became obsoleted after a centuries long history as a 'historical region' in classical antiquity.

Terminology

[edit]

Germania is generally accepted as a Latin word and a toponym. The origin of the term is unknown but attested in use in the Augustan period of the Roman empire, notably in the books of Julius Caesar. In the latin dictionary of Lewis and Short, from 1879, Germania is written as derived from Germani and shortly explained as "the country of the Germans", with reference to the books of Julius Caesar, and then " – divided into Upper and Lower Germany", with reference to Tacitus. According to Jensen & Goldschmidt 1942, the plural form Germaniae could designate the two Roman provinces.

The concept of a Germania has not been exact, and typically used very flexible and subordinate - the encyclopaedic Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde from 1915[2] does not have the entry, neither does the current online version of Encyclopædia Britannica.

Germans - Germani - Deutsch

[edit]A people, calling themselves Germani, has perhaps never been. But, as an exonym, the Germani-name has a long and rich history, from Caesar's Germani to the present-day Germans.

Ein Volk, das sich Germanen nannte, hat es vielleicht nie gegeben. Als Fremdbezeichnung hingegen hat der Germanenname eine lange und reichhaltige Geschichte, von Caesars Germani bis zu den heutigen Germans.

— Pohl 2004, first sentence

German: deutsch is a native appelation, testified to have been around from c. the 7th century, at that time associated with the Frisians.[3] In the 9th century, the Francian king Louis the German was so named, by the scholars of his time, because of his claim to east Francian territory. It was a Latin appellation (Ludovicus Germanicus) and the king's name was not vernacularized before modern times.[4] The east Francian territory loosely corresponds to what had, in the early history of the Franks, been known as Austrasia - the lands of Carolingian mayors. In this way the tradition of Latin and vernacular intermixed terms began. Several languages, including English, derive the name for present-day Deutschland from the Latin term Germania, ie. Germany.

Germania as an ancient expanse

[edit]The classic Greeks knew of Keltoi (Celts), to the far northwest and Scythoi (Skythians), living north and northeast of Donau. Whereas the ethnonym Scythoi was transferred to a place-name Scythia, Celts were the inhabitants of Europe. This ethnography and geography was also in use amongst the scholars in the Byzantine Empire.[5]

The histories of Germania - 1st century BC to 4th century AD

[edit]From the 1st century BC onwards the Germania-region became a politic-military concern for the Romans.[6]

The story of Caesar's Germania

[edit]At c. 70 BC, the Germani king (Latin: rex Germanorum) Ariovist crossed the Rhine to assist the 'Sequaner' against the 'Haeduer'. After the successful campaign, c. 61-60 BC, Ariovist established a position in Alsace, and was mentioned in the Roman senate. When Julius Caesar fought Ariovist, the Germani king lead an army of many tribes: Charudes, Marcomanni, Triboci, Vangiones, Nemetes, Sedusi and Suebi.[7] Julius Caesar recalls, in his book "Commentarii de Bello Gallico", his defeat of the Suebi tribes at the Battle of Vosges (58 BC) and emphasizes Germani tribesmen as savage and a threat to Roman Gaul. Julius Caesar's accounts of barbaric northern tribes could be described as an expression of the superiority of Rome, and including Roman Gaul.[8] Although no certainty has been reached, it has been assumed that the infra-structure of a Roman province was underway - this idea was for example expressed by Theodor Mommsen, but has drawn debate in later years. Todays archaeological knowledge does show that Roman settlements, of a varied kind, existed in the region between the Elbe and the Rhine, both before and after the defeat of Publius Quinctilius Varus in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD.[9]

The story of the two Germaniae

[edit]In the 1st century AD Roman activity continued to characterize the Rhine region. Emperors Vespasian and Domitian further secured the lands along the Danube and Rhine rivers and at the end of the century the military turmoil had accomplished an administrative provincialized consolidation: the establishment of Germania Inferior in the Rhine delta, towards the North Sea and, Germania Superior at the middle Rhine and the region south of the Rhine and Danube upper reaches. The Germaniae provinces was established by Domitian at c. 90.[10]

At the middle Rhine, traces of settlement in both Mainz (Mogontiacum) and Strasbourg (Argentoratum) predates the Roman presence with a millenium, Mogontiacum being the more thriving (French: oppidum hallstattien, c. 6th century BC).[11] The Roman legion camp settlements in Mogontiacum and Argentoratum date from c. the year 14, associated with the legions II., XIV. and XVI., operating in the campaigns of Germanicus.[12] Both cities were regional centers in the beginnings of a Roman order, though, by todays evidence, literary or in archaeology, mainly as military placements.

At the beginning of the 2nd century Roman military advances also included extensive building activities across the Rhine,[13] establishing an advanced frontier - some remains are still visible and protected landmarks, and being listed amongst the World Heritage Sites. These are known as Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes, and enclose a smaller region between the Main, Danube and Rhine rivers. During that century a romanized settlement pattern of villa rustica developed in the Germaniae. Following the reforms of emperor Diocletian, just a small territory between Mainz and Strasbourg remained as Germania Superior, the greater part now being administered separately as Maxima Sequanorum, in the Alsace, Burgund and northern Swiss region. From this region, outside the Germaniae, the archaeological record indicate a wide distribution of villa rusticae dating back to the 1st century AD, and especially around regional centers Augst (Augusta Rauracorum, or Kaiseraugst castrum Rauragense) and Avenches (Aventicum),[14] perhaps a civic environment of municipal functions handling the res publica.

The ending story

[edit]The politic-military development was soon to be characterised by the Roman strategy of foederati-settlements,[15] a politic essentially replacing the strategy of expansion;[16] this is, though, a modern interpretation.[17]

At the end of the 4th century four Francians reached a position as magister militum, Frankish contingents in Roman commission went against a war-train of Sarmatian, Alan and Vandal warrior-troupes marauding in Gaul,[18] and in this way the provincial territories became battlefields as well as strongholds for the new regna in the European continent.[19] At the end of the 5th century Roman bishop Remigius of Reims congratulated Chlodwig on his new responsibility over Belgica II - part of the former Gallia Belgica - and ten years later Chlodwig was baptized in Reims, from hence an event remembered as the beginnings of a catholic Frankenreich - and later France.[20]

The present-day reception of Germania

[edit]

According to Heather 2007 Germania was as well inhabited by other peoples, but even when "Germania as meaning Germanic-dominated Europe"[21] presents a new perception of Germania, it is still the Roman Empire and the manifold peoples - or barbarians - that is Heather's main focus.[22]

In Walter Pohl's view, the historic proces, starting from Ariovist, shows the Roman politic efforts,[23] profiled by personae, and associated with numerous ethnicities. This 'Transformation of the Roman World' has less to do with Germania, as a geographic-historic concept; even the classic invention of the term indicate the focus on peoples, the Germani.

Just as research studies of the literate evidence from Antiquity and medieval times, archaelogical interpretation of found-groups located in pre-Roman or pre-literate Germania has found its natural focus in the search for Ethnos - ethnic groupings - as well as a focus on methodology. Sebastian Brather sees a change in the post-WW2 era, towards a new archaeology (also known as Processual archaeology) influenced by ideas in social science, describing modes of production, the construction of communities and the application of structural analysis - however, contemporary studies of pre-Roman or pre-literate ethnicities in north-Europe are numerous.[24]

Classic literate usage and classic cartography - 1st century BC to 4th century AD

[edit]Itaque ea quae fertilissima Germaniae sunt loca circum Hercyniam silvam, quam Eratostheni et quibusdam Graecis fama notam esse video, quam illi Orcyniam appellant, Volcae Tectosages occupaverunt atque ibi consederunt;

Accordingly, the Volcæ Tectosages, seized on those parts of Germany which are the most fruitful [and lie] around the Hercynian forest, (which, I perceive, was known by report to Eratosthenes and some other Greeks, and which they call Orcynia), and settled there.

Julius Caesar (ed. Holmes) 1914, p. 253 / Julius Caesar (tr. Bohn) 1872, p. 153, [Caes. Gal. 6.24]

The place-name Germania is most probably a reflection of the Roman idea of a territory inhabited by Germani,[25] a "territorial perception of Germani".[26]

Foremost there was a politico-administrative usage through the names given to the two northern provinces along the southern banks of the Rhine: Germania Superior and Germania Inferior. A further distinction between the territories beyond the frontiers and the two Roman provinces was accomplished through the word-compound Magna Germania.[27]

This is the famous naming-sentence, [Tac. Ger. 2.5]:[28]

For the rest, they affirm Germany to be a recent word, lately bestowed: for that those who first passed the Rhine and expulsed the Gauls, and are now named Tungrians, were then called Germans: and thus by degrees the name of a tribe prevailed, not that of the nation; so that by an appellation at first occasioned by terror and conquest, they afterwards chose to be distinguished, and assuming a name lately invented were universally called Germans.

- Claudius Ptolemy, ca. 150 AD

The geography of Magna Germania was, for that age, comprehensively described in Ptolemy's Geography via geographical coordinates of the known cities. By means of a geodetic deformation analysis carried out by the Institute of Geodesy and Geoinformation Science at the Technical University of Berlin as part of a project of the German Research Association under the direction of Dieter Lelgemann (2007-2010), many historical place names have been localized and associated with place names of the present day.[29]

The very long duree - literate usage from the 5th to the 20th century

[edit]The literate preoccupation, to represent the enigma of an ancient past, mostly took use of the personified, or existentially directed form.[30] According to Pohl 2004,[31] the early medieval ethnic identities, such as Franks, Alemanni and Burgundians, sought an relatedness to Romans, as expressed, for example, in origo gentis - tales of origins - which effectively replaced the idea of Germani. This changed in the renaissance, where humanist scholars instead told of the natural character of Germani, contrasting both the contemporary and the Roman population. Whereas this might have been a scholarly concern, the topos evolved as a both romantic and politic mythos in the modern age; a way of identification with the ancients, expressed in a popular manner.[31] Beyond the plain mentioning of a Germania, the interest for the place-name has been expressed in the art of cartography, stolidly using the geographic indications given in antiquity.

Die Gleichsetzung von germanisch und deutsch meint selbstverständlich nicht die Möglichkeit, das Wort Germani neben anderen zur Bezeichnung der Deutschen des Hoch- und Spätmittelalters zu gebrauchen, sie meint vielmehr die Inanspruchnahme der Germanen, von denen Tacitus und andere antike Autoren - Historiker, Ethnographen und Geographen - berichten, als Deutsche und damit als die Vorfahren der Deutschen des 15. und 16. Jahrhunderts, die Tacitus lesen.

Mertens 2004, p. 39

Germania Antiqua (The old Germania) is the title of a 1616 work, also an early modern historic geography, by Philipp Clüver.

It was through the works of Tacitus and Ptolemy that German scholars discovered a description of their lands, for example in 1579 the Brandenburg priest Christoph Entzelt, who wrote a short German-language local history, describing the Roman campaigns in the lands between the Rhine and the Elbe.[32] In 1724 the association between Germans and Germani was expressed in a programme of Reichs-Historie (History of Sovereignty), by Nicolaus Hieronymus Gundling, although with no emphasis on the place-name Germania.[33] The trivial use of the term 'Deutschland' to refer to the term 'Germania', attested from scholarly writings since the 15th century, is, so to speak, accidental: as following Mertens 2004, a consequence of the word-association 'deutsch' - 'germanisch', that occurs from the 15th century. This usage did not cover the appelation of inhabitants in the Deutschen territories in the Middle Ages, but signifies the approbiation of the Germani, such as described by Tacitus, as forefathers of the Germans in the Renaissance age.[34]

|

|

|

In the 1920's and 1930's the reception of Germania produced a couple of new word constellations. First, in 1925, a Germania Judaica came to; an academic concept meant to focus research on the Jewish community in Germany - nota bene not in Germania.[35] A study by the archaeologist Sture Bolin in 1926, concerning hordes of Roman and Byzantine coins, spoke of a Swedish: fria Germanien, and in Bolin 1930 German: freies Germanien. This fria Germanien pointed to found-group localities outside the Roman provinces, and the term caught on - also in the latinized form Germania Libera - perhaps because scholars presumed a certain authenticity from the renaissance interpretation of the Germanic societal form, and as well because of the geographic flexibility. Neumaier 1997 mentions as examples here Eggers, (1951) "Der römische Import im freien Germanien" together with a German-language atlas from 1988. But, although the renaissance scholars did put weight on the freedom of the ancients, the exact term Germania Libera was not used.[36] Then, in 1932, there was a Germania Romana and a corresponding Romania Germanica, signifying how a certain Germanic dialect was influenced by the Roman language, or vice-versa how a certain Romanic dialect was influenced by the Germanic language.

Germania Slavica was first coined after the World War, and according to Kahle 1981 probably from the circles around Walter Schlesinger, but then virtually launched by W.H.Fritze in 1976, Freie Universität Berlin, as a study field, and also a publications-series of the same name. Much similar to Germania Judaica, the Germania Slavica does not refer to Germania but - partly - to a Germany, though pointing back a full millenium before the constitution of the German Republic, in the 19th century. It is especially the eastern lands of the Teutsche Empire but as well regions stretching into Poland and the Czechoslovakia. Another similarity is the focus on the interactions of, and influences between ethnic groups, explicitly referring to Germanic and Slavic ethnicity. The interdisciplinary approach involved as well medieval archaeology, ethnology, history of law, place-name studies and art history, and in a like manner sought a 'bilateral' cooperation, by drawing in researchers from Poland and the Czechoslovakia.[37]

Examples of present-day usage

[edit]- A historical perspective

The Oxford Handbook 2020 suggests a contemporary value in comprehending Germania:[38]

Rome had to deal with many other barbarians' on the peripheries of her sprawling empire, [..] by no means least, the peoples of Germania. [..] of these great cultural encounters and confrontations, that with Germania has always had special resonance in western and central Europe. [..] for many other Europeans, it was seen as key to the genesis of their own cultures and identities. [..] Iconically, Franks and others turned Gaul into France, while traditionally Angles, Saxons, and Jutes transformed most of the province of Britannia into England. For understanding Roman and later Europe, ancient Germania still matters.

- A medievalist perpective

Peter Heather suggests Germania as defined by the presence of Germanic-language groups holding a dominant position amongst non-Germanic-speaking groups:[39]

While the territory of ancient Germania was clearly dominated in a political sense by Germanic-speaking groups, it has emerged that the population of this vast territory was far from entirely Germanic [...] [Germanic] expansion did not annihilate the indigenous, non-Germanic population of the areas concerned, so it is important to perceive Germania as meaning Germanic-dominated Europe.

- A romantic perspective

The Encyclopædia Britannica suggests the trivial association between Germania and Germany:[40]

The conception of Arminius as a German national hero reached its climax in the late 19th century. It could claim support from Tacitus’s judgment of him as “unquestionably the liberator of Germany” (liberator haud dubie Germaniae); but it is clear that in Arminius’s day a united “Germany” was not even an ideal.

- A linguistic perspective

Lehmann & Slocum suggest the (relative) primeval nature of the peoples of Germania, apropos Indo-European languages:[41]

The people of Gaul had obviously been influenced by the Greeks and Romans, while the people of Germania have resisted such influences. The account of the people of Germania consequently provides information on the conditions that applied in previous centuries, possibly even in late Indo-European times.

See also

[edit]Literature

[edit]- Brather, Sebastian (2004). "Fragestellung: „ethnische Interpretation" und „ethnische Identität"". Ethnische Interpretationen in der frühgeschichtlichen Archäologie: Geschichte, Grundlagen und Alternativen. Ergänzungsbände zum Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (in German). Vol. 42. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 1–10. doi:10.1515/9783110922240. ISBN 3110180405.

- Geuenich, Dieter (2005). Geschichte der Alemannen. Urban-Taschenbücher (in German). Vol. 579 (Zweite überarbeitete Auflage 2005 ©1997 ed.). Stuttgart: Kohlhammer. ISBN 3170182277.

- Hatt, Jean-Jaques (1976). "Résultats historiques des fouilles de Strasbourg et de Metz" (PDF). Mémoires de l'Académie nationale de Metz (in French): 121–128.

- Heyen, Franz-Josef (1979). "Das Gebiet des nördlichen Mittelrheins als Teil der Germania prima in spätrömischer und frühmittelalterlicher Zeit". In Werner; Ewig (eds.). Von der Spätantike zum frühen Mittelalter (in German). pp. 297–315.

- Jensen, J. Th.; Goldschmidt, M. J. (1942). "Germani". Latinsk-dansk Ordbog. København ; Kristiania: Nordisk forlag.

- James, Simon; Krmnicek, Stefan (2020). "Editor's introduction". In Simon James; Stefan Krmnicek (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Roman Germany. Oxford University Press. pp. xi–xxii. ISBN 0199665737.

- Kahl, Hans-Dietrich (1981). "Germania Slavica - Ein neues Vorhaben zur deutsch-slawischen Geschichte in Mitteleuropa und seine Bedeutung für die Forschung der Ostalpenländer". Mitteilungen des Instituts für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung (in German): 93–106. doi:10.7767/miog.1981.89.12.93.

- Kleineberg, Andreas (2010). Kleineberg, Andreas; Marx, Christian; Knobloch, Eberhard; Lelgemann, Dieter (eds.). Germania und die Insel Thule. Die Entschlüsselung von Ptolemaios' "Atlas der Oikumene" [Germania and Thule Island. The Decipherment of Ptolemy's "Atlas of the Oikoumene"] (in German). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. ISBN 978-3-534-23757-9. OCLC 699749283.

- Martin, Max (1979). "Die spätrömisch-frühmittelalterliche Besiedlung am Hochrhein und im schweizerischen Jura und Mittelland". In Werner; Ewig (eds.). Von der Spätantike zum frühen Mittelalter (in German). pp. 411–446.

- Mertens, Dieter (2004). "Die Instrumentalisierung der „Germania" des Tacitus durch die deutschen Humanisten". In Heinrich Beck (ed.). Zur Geschichte der Gleichung „germanisch - deutsch“ : Sprache und Namen, Geschichte und Institutionen. Ergänzungsbände zum Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. Vol. 34. Berlin: De Gruyter. pp. 37–101.

- Neumaier, Helmut (1997). "'Freies Germanien'/'Germania libera' - Zur Genese eines historischen Begriffs". Germania (in German): 53–67. doi:10.11588/ger.1997.70977.

- Pohl, Walter (2004). Die Germanen. Enzyklopädie Deutscher Geschichte (in German). Vol. 57. München: Oldenbourg. ISBN 3486567551.

- Pohl, Walter (2005). Die Völkerwanderung - Eroberung und Integration. Enzyklopädie Deutscher Geschichte (in German) (Zweite überarbeitete Auflage 2005 ©2002 ed.). Stuttgart: Kohlhammer. ISBN 3170189409.

English language sources

[edit]- Cuff, David B. (2009). "Die Schlacht im Teutoburger Wald: Arminius, Varus und das römische Germanien - Reinhard Wolters, Die Schlacht im Teutoburger Wald: Arminius, Varus und das roemische Germanien. München: Verlag C.H. Beck, 2008. 192. ISBN 9783406576744 €18.90". Bryn Mawr Classical Review (bmcr.brynmawr.edu).

- Heather, Peter (2007). The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199978618.

- Martin, Stéphane (2018), "Germanicus on the Upper-Rhine. Earlier Tiberian contexts from Germania Superior", in Stefan Burmeister; Salvatore Ortisi (eds.), Phantom Germanicus. Spurensuche zwischen historischer Überlieferung und archäologischem Befund, Materialhefte zur Ur- und Frühgeschichte Niedersachsens, vol. 53, Rahden, pp. 253–272, ISBN 9783896468451

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - O'Donnel, James (2005). "P. J. (Peter J.) Heather, The fall of the Roman Empire. London: Macmillan, 2005. xvi, 572 pages, 16 unnumbered pages of plates : illustrations, maps, portraits ; 25 cm. ISBN 0333989147". Bryn Mawr Classical Review (bmcr.brynmawr.edu).

- Ogg, Frederic Austin (1908). A Source Book of Medieval History - documents illustrative of European life and institutions from the German invasions to the renaissance. New York: American Book Company.

Further reading

[edit]- Laurent, Peter Edward (1840). "Germania". A Manual of Ancient Geography. Oxford: Henry Slatter. pp. 163–168.

- Gustav Solling (1863). Diutiska - an historical and critical survey of the literature of Germany, from the earliest period to the death of Göthe. London: Trübner and Co.

- Bolin, Sture (1930). "Die Funde römischer und byzantinischer Münzen im freien Germanien" [Findings of Roman and Byzantian coins in the free Germania]. Bericht der Römisch-Germanischen Kommission (in German). 19. Frankfurt am Main: Joseph Baer & Co.: 89–145. doi:10.11588/berrgk.1930.0.33420.

- Joachim Werner; Eugen Ewig, eds. (1979). Von der Spätantike zum frühen Mittelalter: aktuelle Probleme in historischer und archäologischer Sicht. Vorträge und Forschungen/Konstanzer Arbeitskreis für mittelalterliche Geschichte (in German). Vol. 25. Sigmaringen: Jan Thorbecke Verlag. eISSN 2363-8664. ISBN 3799566252. ISSN 0452-490X.

- Lehmann, Winfred P.; Slocum, Jonathan (2002). "Lesson 3". Early Indo-European Online>Latin Online. Linguistics Research Center, University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- Timpe, Dieter (2009). "Mitteleuropa in den Augen der Römer". Bonner Jahrbücher (in German). doi:10.11588/bjb.2007.0.33141.

- Petra G. Schmidl (June 2012). "[REVIEW] Andreas Kleineberg;, Christian Marx;, Eberhard Knobloch;, Dieter Lelgemann. Germania und die Insel Thule: Die Entschlüsselung von Ptolemaios' "Atlas der Oikumene.". 131 pp., maps, bibl., index. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 2010. €29.90 (cloth)". Isis. doi:10.1086/667485.

- Drinkwater, John Frederick (2012). "Germania". In Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther (eds.). The Oxford Classical Dictionary (4 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191735257. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, ed. (1 January 2020). "Arminius". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Retrieved 26 July 2020 – via www.britannica.com.

{{cite web}}:|editor=has generic name (help)

Primary sources

[edit]- Philipp Clüver (1616). Germania antiqua (in Latin). Leiden: Elzevier.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lay-url=ignored (help)

- Julius Caesar

- Thomas Rice Holmes, ed. (1914). C. Iuli Caesaris Commentarii rerum in Gallia gestarum VII, A. Hirti Commentarius VIII (in Latin) (With an English introduction ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. - at www.perseus.tufts.edu

- Julius Caesar (1872). Caesar's Commentaries on the Gallic and civil wars, with the supplementary books attributed to Hirtius : including the, Alexandrian, African and Spanish Wars. Harper's New Classical Library. Translated by W. S. Bohn. New York: Harper & brothers. - At perseus.tufts.edu

- Tacitus

- Henry Furneaux, ed. (1900). "Germania [de Origine et situ Germanorum liber]" [Book of the origins and location of the Germani]. Cornelli Taciti opera minora [Minor works of Cornelius Tacitus]. Oxford Classical Texts (in Latin). Oxford: Clarendon Press. - "de Origine et situ Germanorum liber" at www.perseus.tufts.edu

- Tacitus (1910). "Tacitus on Germany". In Charles W. Eliot (ed.). Voyages and travels : ancient and modern, with introductions, notes and illustrations. The Harvard classics. Vol. 33. Translated by Thomas Gordon. New York: P. F. Collier and son. pp. 95–123.

External links

[edit]- Map of locations in Germania according to Ptolemaios, based on the coordinates from Kleineberg 2010. (Google user map)

- Paul Halsall, ed. (1996–2020). "Selected Sources: Studying History". Internet Medieval Sourcebook. Fordham University Center for Medieval Studies.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link)

References

[edit]- ^ cf. [Tac. Ger. 1], Tacitus (tr. Gordon), 1910, p. 95, Tacitus (ed. Furneaux), 1900, [pdf-p.15]

- ^ Johannes Hoops, ed. (1915). F-J. Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (in German). Vol. 2. Straßburg: Trübner.

- ^ Oxford Handbook 2020, p. xvii

- ^ Pohl 2004, p. 4

- ^ Pohl 2004, p. 3

- ^ cf. Oxford Handbook, p. xi (first sentence)

- ^ cf. Pohl 2004, p. 14, referring to [Caes. Gal. 1.31.10] and [Caes. Gal. 1.51.2]; cf. Julius Caesar (ed. Holmes) 1914, pp. 37&61 / Julius Caesar (tr. Bohn) 1872, pp. 23&40

- ^ Ogg 1908, pp. 19–21

- ^ Pohl 2004, pp. 94–97; Martin 2018, pp.267-268 [postprint:pp.11-12]; province: Cuff 2009

- ^ Heyen 1979

- ^ Hatt 1976, p. 122

- ^ Martin 2018, p.267 [postprint:p.9]

- ^ Heyen 1979

- ^ Martin 1979

- ^ Pohl 2004, pp. 98–100; Pohl 2005, pp. 51–52; cf. Geuenich 2005, p. 23

- ^ Pohl 2005, pp. 32–33; similar Oxford Handbook 2020, p. xi

- ^ cf. Pohl 2005, 51-52; with note 45

- ^ Pohl 2005, pp. 171, 72–75

- ^ Pohl 2005, passim; also pp.36-37,219-221

- ^ Pohl 2005, pp. 176–179

- ^ Heather 2007, p. 53

- ^ O'Donnel 2005

- ^ Pohl 2005, pp. 26–28

- ^ Brather 2004

- ^ cf. Oxford Handbook, p. xvii

- ^ Pohl 2004, p. 3:German: territorialer Germanenbegriff

- ^ cf. Pohl 2004, pp. 58–59

- ^ Tacitus (tr. Gordon), 1910, p. 96, Tacitus (ed. Furneaux), 1900, [pdf-p.16]

- ^ Kleineberg 2010

- ^ Pohl 2005, pp. 17–23

- ^ a b Pohl 2004, pp.1,59-62 passim

- ^ cf. Neumaier 1997, pp. 55–59, with an excerpt from Entzelt pp.57-59.

- ^ Neumaier 1997, pp. 54–55

- ^ Mertens 2004, pp. 38–39

- ^ Kahle 1981, p. 93

- ^ Neumaier 1997, passim, examples:pp.53-54

- ^ Kahle 1981

- ^ Oxford Handbook 2020, p. xi

- ^ Heather 2007, p. 53

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica 2020

- ^ Lehmann & Slocum 2002

[[Category:Germania| ]] [[Category:Historical regions]]