User:Thomaschina03/Constitution of the Roman Republic

This page may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (March 2008) |

|

|---|

| Periods |

|

| Constitution |

| Political institutions |

| Assemblies |

| Ordinary magistrates |

| Extraordinary magistrates |

| Public law |

| Senatus consultum ultimum |

| Titles and honours |

The constitution of the Roman Republic or mos maiorum (Latin for "custom of the ancestors") was an unwritten set of guidelines and principles passed down mainly through precedent.[1] Concepts that originated in the Roman constitution live on in constitutions to this day. Examples include checks and balances, the separation of powers, vetoes, filibusters, quorum requirements, term limits, impeachments, the powers of the purse, and regularly scheduled elections. Even some lesser used modern constitutional concepts, such as the bloc voting found in the electoral college of the United States, originate from ideas found in the Roman constitution.

The constitution of the Roman Republic was never formalised, and operating largely on precedent it constantly evolved throughout the life of the republic. Throughout the 1st century BC, the power and efficacy of the Roman constitution was progressively undermined by changes in the political and international landscape. The series of civl wars, which culminated in Gaius Octavian's victory at the Battle of Actium, trampled over many of the constitutional forms of the Republic. Octavian in restoring peace to the Mediterranean, dramatically changed the nature of Roman government, by creating the Principate. This retained many Republican forms, but saw the effective concentration of power into the hands of the emperor.

History and Origin[edit]

The Roman Constitution has its origins in the Roman monarchy which ended with the tyrannical reign of Lucius Tarquinius Superbus. During this period the structure of the Roman state was akin to that of many Greek cities. Power in the state was concentrated effectively and theoretically in the hands of the king. Nevertheless, as in Greek cities, the king's rule as justified because he acted for the benefit of the people of the city. The citizen body, was viewed by later Roman thinkers[2] even at this time as being sovereign.

The assassination of the last king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, was justified because as a tyrant he was no longer acting in the interests of the sovereign people of Rome.

The Romans were believed to have suffered under tyranny during the Roman Kingdom. The tyranny lasted throughout the life of the kingdom. This tyranny reached its height during the reign of the final king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus. Tarquin ruled with violence and terror[3]. He destroyed the altars and shrines on the Tarpeian Rock, which infuriated people throughout the city. He repealed many of the earlier reforms that prior kings had enacted. He was the first king to disregard the advice of the senate. He would act as sole judge over capital cases, and would often execute senators and citizens for little or no reason. He would also order citizens to surrender their land and property to him[3]. His son, Sextus Tarquinius, raped the wife of a patrician senator, named Lucretia[3]. The rape caused a revolt. In 509 BC, the revolt resulted in Lucius Junius Brutus, a partisan of Lucretia's husband, leading an uprising that expelled Tarquin from the city[3]. After Tarquin had been expelled, the senate decided not to elect another king. Instead, they decided to divest all powers of the king into the Roman Senate. And for that first year, both Brutus and Lucretia's widower, Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus, would be consul[3].

In subsequent years, Romans established a complex set of checks and balances, to ensure that Rome would never again suffer under the tyranny that it had lived under when the kings ruled the city[3]. In the early republic, the senate granted most of their powers to the two consuls (then called praetors) during the annual consular term. However, as time went on, more offices were created, with more officers being elected to each office every year. The result was the dilution of early consular power, and the distribution of such power, to more and more individuals. The result was the ultimate reduction in the power that any single individual would hold in any given year.

Because of what happened during these early years, Romans throughout the era of the republic were concerned about what might happen if one person accumulated too much power. Therefore, the Roman constitution relied heavily on mechanisms that would prevent any one person from amassing too much unchecked power. During the two consulships, and the dictatorship of Lucius Cornelius Sulla, laws were passed to strengthen the weakening constitution. Sulla took power away from the popular assemblies, and transferred that power to the senate. During the later years of the republic, struggles between the aristocracy, and all other People of Rome, had caused a systemic weakening of the constitution. This struggle had been greatly exacerbated during the decades leading up to Sulla's dictatorship, due to the constant state of warfare Rome was finding itself in. Sulla was aware that a future tyrant may use popularity with the people, in order to seize complete power. Thus Sulla viewed the senate as the only institution that would stand in the way of such a future tyrant.

The memory of tyranny under the kings lived well into the life of the republic. It was this fear that enforced the constitution of the Roman Republic. But the constitution was unwritten, and no one was ever given the task of enforcing it. Thus, it had power and legitimacy only so long as those in power allowed it to have that power and legitimacy. Towards the end of the 2nd century BC, and into the 1st century BC, the fear of the kings had been replaced by two new fears. Due to longer, and more protracted warfare, executive power was bloating beyond its constitutional limits. Struggles were becoming more violent, between the educated aristocracy, which knew the dangers of tyranny, and the people. The common people were more interested in jobs, and their own livelihood, than they were in abstract constitutional issues. It was this that lead to the rise of Gaius Julius Caesar. Caesar seized power, using the same popular support that Sulla had feared. Sulla's reforms, meant to strengthen the senate, had been dismantled in the years following his death. Caesar's popular support proved too much for the entrenched optimates in the senate. Caesar overpowered the senate, and seized complete power. Caesar was assassinated on the Ides of March, by a Roman who had claimed descent from the senator who had expelled Tarquin.

The Senate[edit]

Under the Constitution of the Roman Republic, the Senate was the chief foreign policy-making branch of Roman government. All magistrates with imperium powers (the power to command armies) answered to the senate. According to the Greek historian Polybius, the senate was the predominate branch of government.[4] Polybius noted that it was the consuls who lead the armies and the civil government in Rome, and it was the legislative assemblies which had the ultimate authority over elections, legislation and criminal trials. However, since the senate controlled money, administration, and the details of foreign policy, it had the most control over day-to-day life.[4]

The senate's place in the republic can be seen by its place in the symbol of Roman state authority, Senatus Populusque Romanus ("The Senate and the People of Rome", or SPQR). This was the stamp of power, authority and approval (political as well as religious) that the Roman legions and their golden eagles marched under as they conquered the Mediterranean world.[1]

The senator and former-consul Cicero also believed the senate to be superior to the other branches of government.[5] Cicero noted that the senate was a self-sustaining and continuous body. In contrast, all magistrates (other than censors) left office together at the end of each year. Cicero believed this partly because of the senate's ability to set in motion events to replace a consul, if a consul were to leave office. The consuls, on the other hand, typically did not have the power to alter the composition of the senate. Cicero also noted the powers of the office of interrex (interregnum). The office of interrex was an office that could be used to fill vacancies if all curule magistrates (consuls, praetors and dictators) were to leave office.[5]

History of the Senate[edit]

The word senate derives from the Latin word senex, which means "old man". Therefore, senate literally means "board of old men." According to legend, the Roman Senate was founded by Romulus in the year 753 BC[6]. This was the year that he founded the city of Rome, and became its first king. The senate, created to advise Romulus and to aid in the administration of the city,"[1] originally consisted of 100 senators of Latin origin[6].

When the king Numa Pompilius died in 672 BC, the popular assemblies elected Tullus Hostilius king. The senate ratified the election[7]. In 578 BC, Tarquinius Priscus died and Servius Tullius became king following his election by the popular assemblies and confirmation by the senate[3]. In these two instances, Rome displayed some of its first uses of Greek-style checks and balances.

During his reign, Romulus brought the Sabines into the kingdom, following the Rape of the Sabine Women[6]. The king Tarquinius Priscus later enlarged the senate to 200, by adding 100 Sabine senators.[7]. Later, the first consul, Lucius Junius Brutus, enlarged the senate to 300 members, by adding 100 Etruscan senators[3]. At the time, a similar proportional ethnic division existed in both the Comitia Centuriata and the Comitia Curiata (which were the only two major popular assemblies to exist during the early republic). In the case of the senate and the Comitia Centuriata, this ethnic breakdown eroded over time.

The senate continued to consist of 300 members until the final century of the republic, when Lucius Cornelius Sulla increased the membership to 600 around the year 88 BC.[8] Several decades later, Julius Caesar increased the size of the senate to 900.[9] Early in his reign, the Emperor Augustus expelled 200 senators. In 18 BC, he expelled another 100, which brought the size of the senate back down to 600.[10]

Romulus called these senators patres ("fathers"). Many years later, a group of plebeians were drafted into the senate (conscripti). The two terms were merged, and senators would eventually be called Patres et Conscripti (Conscript Fathers, or Fathers and Conscripted Men).

During the years of the kingdom, the senate was primarily responsible for the election of a new king (rex)[11]. Once a king died, the powers of the king would divest into the senate. The senate would then appoint one of its members as the interrex (Latin for interim king). The interrex would serve for five days[11]. At the end of the five days, a new interrex would be appointed. This would continue until a new king was elected. When the interrex found an acceptable nominee, he would present this nominee to the senate. If the senate approved, the interrex would convene the Curiate Assembly (which was the only legislative body at the time with any power) to formally elect the new king[3]. After a religious ceremony, to ensure that the nominee was acceptable to the Gods, the Curiate Assembly would meet again. It would grant imperium powers to the king-elect. This would give the new king the ability to command armies. At this point, the process was complete.

When the last king, Tarquinius Superbus was expelled in 509 BC, the senate decided not to nominate another king[3]. Since the powers of the king had been divested to the senate, the senate decided to retain these powers. The senate elected two leaders, called praetors. These leaders would eventually come to be called consuls. It was at this point that the Roman Republic was born, and the constitution was created. It was also at this point that the Roman senate transitioned from being an advisory body of town elders, to a policy-making body of former magistrates.

In the middle of the fourth century BC, the Lex Ovinia law passed. This law set the rules for senate membership.[5] It required censors to give preference to ex-magistrates when enrolling new senators. It also allowed the censors to appoint new senators. Financial requirements were also set for membership.[12]. One benefit of this law, other than increasing the level of experience of the average senator, was that the appointment of new senators became more objective and standardized. Therefore, it became harder for censors to appoint senators based on personal or partisan biases. It also gave an extra incentive for magistrates to be effective in their offices, because a successful term in office meant that the magistrate would probably be appointed to the senate. In addition, it meant that most senators had been indirectly elected to the senate, since one had to be elected by the people to any magisterial office.

During the early and middle republic, one was not given automatic senate membership upon being elected Plebeian Tribune. However, in 122 BC, the Lex Atinia was enacted by the Plebeian Council. This law required that any person elected Tribune be given automatic membership in the senate. In 81 BC, the dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla enacted a law that required any person elected quaestor to be given automatic senate membership.[13]

As Rome expanded, new magistrates were needed to serve as governors of the new provinces. To fill these new governorships (as well as their staffs), more magistrates (especially praetors) had to be elected. Over time, the result was more senators with magisterial experience. As a consequence, it became harder for magistrates to ignore the advice of the senate.

Senatorial Powers[edit]

The source of the senate's power was its auctoritas (Latin for "authority").[14] This was different from the source of the power of the consuls or praetors (imperium), the tribunes (their sacrosanctity) or the assemblies (the sovereignty of the People of Rome). The senate's auctoritas included religious authority, as well as constitutional and legal authority. Whereas imperium was the power to give commands, and sacrosanctity derived from being a representative of the People of Rome, in practice auctoritas derived from the esteem and prestige of the senate.[14] This esteem and prestige was based on both precedent and custom (mos maiorum), as well as the high caliber and prestige of the senators. As the senate was the only political institution that was eternal and continuous (compared to, for example, the consuls, whose terms expired at the end of every year), to only it belonged the dignity of the antique traditions.[14] As Cicero notes, only the senate was considered to have had an unbroken lineage, going back to the very founding of the republic.[5] All powers of the senate derived from its auctoritas.

The focus of the Roman senate was directed towards foreign policy. While its role in military conflict was officially advisory, the senate was ultimately the force that conducted those conflicts. The relationship was effectively one of agency, rather than independence. The consuls would have formal command over the armies. However, the consular command of those armies was directed by the senate.

In addition, the senate sent and received foreign ambassadors, and appointed provincial governors[15]. It appointed officials to manage the public lands, and it oversaw the religious institutions. The senate had complete power over the treasury, and thus only it could appropriate government funds[15]. Since the senate funded the operations of the magistrates, magistrates could only launch wars when the senate provided funding. And since a Triumph required the expenditure of money, only the senate could authorize payment for a Triumph.[16] The senate also decided criminal cases involving treason, conspiracy or assassination.Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page). Each senatus consultum included the name of the presiding magistrate, the place of the assembly, the dates involved, the number of senators who were present at time the motion was passed, the names of witnesses to the drafting of the motion, and the substance of the act. In addition, it included the capital letter "C", to indicate that it had been approved by the senate. The document was then deposited in the aerarium (treasury).[17]

At the end of each consular term, the lame duck consuls would have to give an accounting of their administration to both the senate and people.[18]

While the senate could influence the enactment of laws, it did not formally make those laws. The assemblies, which were considered the embodiment of the People of Rome, made domestic laws which governed the people.

Senate Procedure[edit]

Every senate meeting would occur in an inaugurated space (a templum). Before any meeting could begin, a sacrifice to the Gods would be made, and the auspices would be taken. The auspices were taken in order to determine whether that particular senate meeting held favor with the Gods.[19]

In the later years of the republic, attempts were made by the aristocracy to limit the democratic impulses of some of the senators. Laws were enacted to prevent the inclusion of extraneous matters in acts before the senate. In addition, omnibus bills were outlawed.[20] Omnibus bills are bills with a large volume of often unrelated material, which is enacted by a single vote. Today, the United States Senate has similar rules, which are called the "Byrd Rules". Laws were also enacted to strengthen the requirement that three days pass between the proposal of a bill, and the vote on that bill.[20] The United States Senate, in contrast, requires two days between a the proposal of a bill, and the vote on that bill.[20]

During his dictatorship, Julius Caesar enacted laws that required the publication of resolutions. This publication, called the acta diurna, or "daily doings", was meant to increase transparency and minimize the potential for abuse.[21] This was similar to the Congressional Record of the United States Congress. This publication would be posted in the Roman Forum. From these postings, copies would be transcribed, and sent by messengers throughout Italy and the outer provinces.[21]

Venue of Senate Meetings[edit]

Meetings could take place either inside or outside of the formal boundary of the city (the pomerium). However, all meetings took place no further than approximately one mile outside of the pomerium[15]. As long as one was within one mile (1.6 km) of the pomerium, they were inside the political boundary of the city. Senate meetings could take place outside the pomerium for several reasons. The senate might wish to meet with a magistrate (such as a consul) with imperium. By meeting outside of the pomerium, that magistrate would not have to surrender his imperium by entering the city. In addition, the senate might wish to meet with an individual (such as a foreign ambassador) whom they did not wish to allow inside the city.[22]

There was not a fixed "senate house", where meetings typically took place. There were many venues where those meetings could take place. At the beginning of the consular year, the first meeting would always take place at the temple of Jupiter Capitolinus. Other venues could include the temple of Fides (which was the site of the meeting before the murder of Tiberius Gracchus) or the temple of Concord.[19] Meetings outside of the pomerium could take place in venues such as the temples of Bellona or Apollo.

The Presiding Officer and Senate Debates[edit]

Meetings usually began at dawn. Occasionally, events (such as festivals) could delay the beginning of a meeting. A magistrate who wished to summon the senate would have to issue an order called a cogere. A cogere was generally compulsorily, and senators could be punished if they failed to appear without reasonable cause. Mark Antony, for example, once threatened to demolish the house of Cicero for this very reason.[23]

In general, the senate was directed by the presiding magistrate. Usually the presiding magistrate would be either a consul or a praetor. If both the consulship and the praetorship were vacant, an interrex would preside. An interrex had full consular imperium, and was attended by twelve lictors (as were the consuls). However, he had to be both a senator and a patrician, and the term in office always expired after five days.[11] By the later republic, tribunes could also preside over the senate.[15]

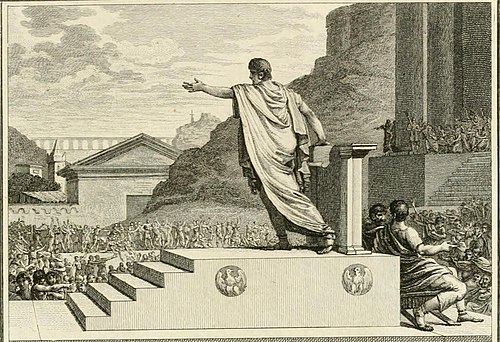

While in session, the senate had the power to act on its own (even against the will of that magistrate) if it wished. The presiding magistrate would often begin each meeting with a speech called a verba fecit.[24] Often this opening speech was brief, but it could be a lengthy oration if the magistrate wished it to be. The presiding magistrate would then begin a discussion on an issue. He would refer the issue to the senators, and they would discuss the matter one at a time by order of seniority[15]. The first to speak was usually the princeps senatus (the most senior senator)[15]. Then, other consulares (ex-consuls) would speak, one after the other. After all consulares spoke, the praetors and ex-praetors would speak. This would continue, until the most junior senators had spoken[15]. A senator could make a brief statement, discuss the matter in detail, or talk about an unrelated topic. All senators had to speak before a vote could be held. Since all meetings had to end by nightfall[17], a senator could talk a proposal to death (a filibuster or diem consumere), if they could keep the debate going until nightfall.[24]

Acts such as applause, booing or heckling would often play a major role in a debate. Any senator could respond at any point if they were attacked personally. The senate meetings were technically public[15]. This was because the doors were left open, which allowed people to look in. Once debates were underway, they were usually difficult for the presiding magistrate to control. The presiding magistrate typically only regained (partial) control once the debating had ended, and a vote was about to be taken.[25]

Procedure, Minority Rights, and Final Votes[edit]

Quorums were required for the senate to operate. It is known that in 67 BC, the size of a quorum was set at 200 senators by the lex Cornelia de privilegiis. If a quorum existed, then a vote could be held. Unimportant matters could be voted on by a voice vote or a show of hands. However, important votes resulted in a physical division of the house[15], with senators voting by taking a place on either side of the house.

Throughout the history of the republic, until the reign of Augustus, there was an absolute right to free speech in the senate.[15]

Senators had several ways in which they could influence (or frustrate) a presiding magistrate. When a magistrate was proposing a motion, the senators could call consule (consult). This would require that magistrate to ask for the opinions of the senators. The cry of numera would require a count of the senators present (similar to a modern "quorum call"). As with modern quorum calls, this was usually a delaying tactic. Senators could also demand that a motion be divided into smaller motions. When it was time to call a vote, the presiding magistrate could bring up whatever proposals (in whatever order) he wished. The vote was always between a proposal and its negative.[26]

Once a vote was held, any motion that passed could be vetoed (intercessio). Usually, vetoes were handed down by Tribunes. However, in a couple of instances between the end of the Second Punic War and the beginning of the Social War, a consul vetoed an act of the senate. Any act that was vetoed was recorded in the annals as a senatus auctoritas. Any motion that was passed and not vetoed would be turned into a final senatus consultum. These final versions were usually written by the presiding magistrate, sometimes with the help of a few low-ranking senators.[27]

Ethical Standards of Senators[edit]

There were several limitations on personal activities by senators. Since they were not paid,[28] individuals would usually seek to become a senator only if they were independently wealthy. Senators could not engage in banking or any form of public contract. They could not own a ship that was large enough to participate in foreign commerce.[15] They also could not leave Italy without permission from the senate. This is similar to rule VI of the standing rules of the U.S. Senate, which states that any U.S. Senator who wishes to take any leave of absence must get permission from the Senate first.[15]

Censors were the magistrates who enforced the ethical standards of the senate. Whenever a censor punished a senator, they had to allege some specific failing. Possible reasons for punishing a member included corruption, abuse of capital punishment, or the disregard of a colleague's veto, constitutional precedent, or the auspices. Senators who failed to obey various laws could also be punished. While punishment could include expulsion from the senate, often a punishment would be less severe than outright expulsion. While the standard was high for expelling a member from the senate, it was easier to deny a citizen the right to join the senate. Various moral failings could result in one not being allowed to join the senate. Examples would include bankruptcy, prostitution, or a prior history of having been a gladiator. The lex repetundarum of 123 BC made it illegal for a citizen to become a senator if they had been convicted of a criminal offense. [8]

Religious Significance[edit]

The senate was as much a religious institution, as it was a political institution. When Gaius Octavius became the first Roman Emperor, the senate named him Augustus. Like the senate itself, this name had important religious significance. The word meant venerable, and had the same root as the word Augur. The Augurs were religious officials, who would study natural occurrences (called taking the auspices), in order to determine the will of the Gods.

The senate operated while under various religious restrictions. The senate was only allowed to meet in a building of religious significance, such as the Curia Hostilia. Any meetings on New Year's Day would be held in the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus. Any war meetings would be held in the temple of Bellona. Sessions could only be held between sunrise and sunset[17]. In addition, a prayer and a sacrifice, were typically made before the beginning of a session. An augur would take the auspices, to ensure that the session had the approval of the Gods.

The senate also had the ability to deify people. After their deaths, the senate declared both Julius Caesar and Augustus to be divine (the act of making Caesar a God literally made his adopted son, Augustus, the "Son of a God").

The Decline of the Senate[edit]

During his two consulships and his dictatorship, Lucius Cornelius Sulla attempted to strengthen the senate. This was done so that the senate could stop a future general with popular support from seizing complete power. Most of his reforms were dismantled after he died in 79 BC. Following the sacking of the port of Ostia several years after Sulla's death, the senate gave powers to Pompey Magnus that typically only belonged to a dictator [1]. This furthered the weakening of the grip that the senate had over the republic.

When Julius Caesar attempted to seize power, the senate was the only institution standing in his way. He eventually won the power struggle, but was assassinated shortly after. When his adopted son and heir, the emperor Augustus, became the undisputed ruler of Rome, the senate abdicated all of its powers to Augustus. When Augustus died in 14 AD, through his will he passed these powers to his adopted son and heir, Tiberius. The senate simply acquiesced to this transfer.

From this point on, the emperor held all of the power that had been held by the senate, legislative assemblies, and executive magistrates. The senate had ceased to be relevant. From this point, until the fall of the Roman Empire in 476 AD, the senate was little more than an advisory council to the emperor, with no real power. Often the senate ratified the decision to install a new emperor, but this act was purely symbolic. Sometimes, an emperor would be chosen from the ranks of the senate. But after the acquiescence of 14 AD, the senate forever lost its relevance and its power.

The legislative branch[edit]

According to the contemporary historian Polybius, it was the people (and thus the assemblies) who had the final say regarding the election of magistrates, the enactment of new laws, the carrying out of capital punishment, the declaration of war and peace, and the creation (or dissolution) of alliances. The people (and thus the assemblies) held the ultimate source of sovereignty.[29] One can view the Roman legislative branch as being composed of two major popular assemblies, and two minor assemblies that declined in importance in the early republic.

While one can speak of a "legislative branch" of the Roman Republic, the "legislative branch" (like everything else in the unwritten Roman Constitution) existed de facto.[30] One can speak of two primary legislative assemblies, and as a rough approximation, this is a correct interpretation. One can speak of two minor legislative assemblies, and as a rough approximation, this is also a correct interpretation. However, unlike modern legislative assemblies, the Roman assemblies never exited as de jure legal institutions. They only existed because magistrates called the citizens to a common meeting place, presented a matter to be voted upon, and held a vote. As described below (see the discussion on the Comitia, Contio, and Concilium), there were many ways that groups of citizens could organize themselves for various purposes. Thus, one should not assume that any particular Roman assembly (not even a "major" assembly) was more formal or fixed into existence than it truly was.

History of the Roman Assemblies[edit]

Originally, the Comitia Curiata was the only legislative assembly. It was founded during the early years of the Roman Kingdom. It passed all laws, and ratified the election of new kings. According to legend, the Comitia Centuriata was founded by the sixth king, Servius Tullius. The Comitia Curiata fell into disuse during the early years of the Roman Republic.

The basic organizational structure of Roman citizens, and thus of the assemblies, was based on three types of units. The oldest unit was the curiae, which was based on ethnic clans. The next type was the centuriae, which was based on the same organizational structure that was found in the Roman army around the time of the creation of the civil centuriae. The last unit that was created was the tribus, or "tribe". These were based on a person's geographical location, similar to modern congressional districts in the United States. [31]

History of the Comitia Centuriata[edit]

At itspoo poo founding, the Comitia Centuriata mirrored the Roman Army. During this period, citizens fought in militias, where they provided their own weapons and supplies. As such, the more money and property a citizen had, the more responsibilities they would be given as a soldier. And since the Comitia Centuriata was originally designed to mirror the Roman Army, the assembly ultimately became based on property classifications. Just as was the case in the early Roman Army, those who had more money and property had more responsibility and power in this assembly.[32] The result was that the soldiers with more money and property, while fewer in number, actually made up close to a majority of the centuries. And since these higher-ranking centuries always voted before the lower-ranking centuries, the decisions of the assembly tended to reflect the will of the nobility, rather than the common people.

History of the Comitia Tributa[edit]

The first tribes were created by the king Servius Tullius for purposes of the census, the levying of troops, and the collection of taxes. [33] The tribes were organized into a comitia for voting around 495 BC. In 471 BC, the election of plebeian magistrates (including Tribunes) was transfered from the Comitia Curiata to the Comitia Tributa. [34] At that point, the Comitia Tributa consisted of four urban tribes and seventeen rural tribes. In 241 BC, another fourteen rural tribes were added, to help adjust the assembly for the increased population of the republic. The final two new tribes, the Velina and Quirina, increased the total number of tribes to thirty-five. The fourteen new tribes corresponded to people who lived well beyond the city of Rome (the seventeen original rural tribes corresponded to people who lived in rural districts near the city of Rome). While attempts were made in later years (in particular, around the time of the Social War) to expand the number of tribes, the numbers were never again permanently increased.[35] Due to the fact that it was easier to gather thirty-five tribes into a single place than 193 centuries, it was the Comitia Tributa that ultimately passed most laws.

Major Laws[edit]

Cicero mentions a law that was passed, probably after the controversial consular election of Curius Dentatus in 274 BC, called the lex Maenia. The law repealed the authority of the senate to veto election results.[36] In 287 BC, abuses by creditors led to the last plebeian secession. The dictator Quintus Hortensius ended the secession by enacting a series of laws. The most important of these laws, the lex Hortensia, mandated than any plebiscite passed by the Plebeian Council would have the full force of law. Plebiscites differed from laws (Latin: lex) passed by the Comitia Centuriata and the Comitia Tributa, because both of these comitia were dominated by patricians and aristocratic plebeians. [36] In contrast, the Plebeian Council, which passed most plebiscites, was less aristocratic. In 98 BC, the lex Caecilia Didia was passed, which allowed the senate to declare that a law passed improperly by an assembly did not have to be obeyed by the people.

History of Balloting[edit]

Originally, votes were cast by placing a pebble into a jar. But during the final century of the republic, votes transitioned from pebble to written ballot. The lex Gabinia was passed in 139 BC, and required written ballots to be cast when elections were being conducted. The lex Cassia of 137 BC required written ballots to be cast when non-capital trials were being conducted. The lex Papiria of 131 BC required written ballots to be cast when legislation was being voted upon. And the lex Coelia of 106 BC required written ballots to be cast when capital trials were being conducted. If an elector wanted to vote "aye", he would write a "V" on his ballot (for VTI ROGAS). If the elector wanted to vote "nay", he would write an "A" on his ballot (for ANTIQVO).[37] These reforms had been opposed by the aristocracy, because it was more difficult for the aristocracy to know how individual electors voted when votes were cast by (in effect, secret) ballot.[38]

Roman Assemblies Contrasted With Modern Assemblies and Modern Referenda[edit]

Most modern legislative assemblies are bodies consisting of elected representatives. Their members typically propose and debate bills. These modern assemblies use a form of representative democracy. In contrast, the Roman assemblies used a form of direct democracy. The assemblies were bodies of ordinary citizens, rather than elected representatives. In this regard, bills voted on (called plebiscites) were similar to modern popular referenda.

Unlike many modern assemblies, Roman assemblies were not bicameral. That is to say that bills did not have to pass both major assemblies in order to be enacted into law. In addition, no other branch had to ratify a bill in order for it to become law. The arrangement is similar to what exists in many countries today. In modern countries, referenda become law after they are passed by a majority of voters. The need for another governmental institution to ratify this popular decision usually doesn't exist.

Members also had no authority to introduce bills for consideration. Only executive magistrates could introduce new bills. This arrangement is also similar to what is found in many modern countries. Usually, ordinary citizens cannot propose new laws for their enactment by a popular election.

Unlike many modern assemblies, the Roman assemblies had judicial functions, due to the fact that the Roman Republic didn't have a formalized court system.

Comitia, Conventio, Concilium[edit]

There were two primary types of assembly. The first was the comitia (or comitiatus), which is Latin for "going together". The word comitia is itself plural, with its singular form (comitium) simply meaning "meeting place". Comitia were the avenues through which the popular assemblies would meet for specific purposes, such as to enact laws, elect magistrates, or conduct jury trials. The second was the contio (conventio), which is Latin for "coming together". These were simply forums where Romans would meet for specific unofficial purposes, such as to hear a political speech or to witness a trial (or even an execution). [39] Conventio were simply meetings, rather than any mechanism through which to make legal decisions. As such, the voters would first assemble into conventio to hear debates and conduct other business before voting. After this was complete, the voters would assemble into comitia to actually vote. [40]

The electors would always stand during a meeting of a conventio or a comitia. Several attempts were made to allow sitting during such a meeting. But these attempts were strongly opposed by the aristocracy, because they believed that it would bring Greek luxury and desidia (literally "sitting down on the job"), which was considered unsuitable for a war-like people. [41]

The comitia and the conventio were both specific to their purpose. For example, the comitia tributa was a meeting of all of the People of Rome, organized into their respective tribes. A comitia quaestoria would be a comitia for the purpose of electing a quaestor. In contrast, the concilium (Latin for "council") were forums were specific groups of people would meet. For example, the concilium plebis would be a concilium where plebeians would meet.[42]

While there were only a couple of primary comitia, contio and concilium, the existence (and relevance) of the different types were not as fixed as one might believe. Simply calling a group of people together for a purpose could constitute a comitia, a contio or a concilium. There were many different reasons why one may wish to hold a comitia or a contio, despite the fact that only a couple of comitia dominated over time. Likewise, there were many different groups who might wish to hold a concilium (such as actors, gladiators, or lictors), despite the fact that the concilium plebis was the most prominent of all concilium.

Block Voting Structure[edit]

The assemblies were composed of Roman citizens. Each member of each assembly was grouped into a block of other members (either a century, a tribe or a curia). Each member of a block would vote. The majority vote of the members in each block would determine how the block voted. Only the vote of the entire block would count in deciding the outcome of a proposed action. While each block received one vote, the blocks were not all of equal size, so the votes of some members weighed more heavily than the votes of other members. The majority of blocks would decide the outcome of legislation. In discussing this system in Pro Flacco, Cicero argued that it was the rashness and lack of divisions by unit that caused the Greek cities to vote for "the worst possible measures". [43] This block voting structure was copied by the U.S. Constitution in the design of the electoral college.

Impeachment Powers[edit]

The Roman Assemblies had the power to impeach executive magistrates. Through a simple vote, they could either deprive a magistrate of his imperium powers (depriving him of his legal right to command an army), or deprive him of his office. In 133 BC, the plebeians voted to impeach a tribune attempting to veto an agrarian reform proposed by Tiberius Gracchus, whereafter the law was (illegaly) passed again by vote and subsequently enacted. A similar impeachment was attempted in 67 BC. In the late republic, higher ranking magistrates (especially consuls and praetors), increasingly found themselves the target of impeachment attempts.[44]

Assembly Procedure[edit]

Only one assembly (comitia) could operate at any given point in time. Once a session began, no other comitia could be called until the first comitia had ended its session. However, if a magistrate called a comitia to assemble but proceedings had not yet begun, any consul could "call away" (avocare) the comitia from the magistrate that was summoning that comitia. Praetors also had the power to "call away" a comitia from its magistrate, but only if that magistrate was not a consul (since consuls outranked praetors).[45]

From Announcement to Vote[edit]

Once a pending vote had been announced, a notice would always have to be given several days before the assembly was to actually vote. For elections, at least three market-days (often more than seventeen actual days) had to pass between the announcement of the election, and the actual election. This time period, known as a trinundinum, was the point at which the candidates would interact with the electorate. During this time period, no legislation could be proposed or voted upon. In 98 BC, the lex Caecilia Didia required a trinundinum to pass between the proposal of a law, and the vote on that law.[45]

When an assembly was being used to conduct a trial, the presiding magistrate had to give a notice (diem dicere) to the accused person on the first day of that trial's investigation (anquisito). When each day ended, the magistrate had to give another notice to the accused person (diem prodicere) of the adjournment until the next day. After the investigation was complete, a trinundinum had to elapse before a final vote could be taken with respect to conviction or acquittal.[46]

The Day of the Vote[edit]

Any magistrate had the power to summon an assembly. The electors would first assemble into an unsorted meeting called a conventio. They would stay in their conventio until voting was to begin. [40] Speeches were only made before the conventio if the issue to be voted upon was a legislative or judicial matter. If it was an election, there would be no speeches. Instead, the candidates would campaign by meeting with (and often by bribing) individual electors. [47]

While consuls, praetors and tribunes were the magistrates whom most often summoned the assemblies, aediles could also summon an assembly. In addition, dictators often called assemblies for the enactment of various laws (or for the election of magistrates). A dictator's Magister Equitum (Master of the Horse) also had the power to summon assemblies.[42]

Before any session could begin, the auspices would have to be taken. This was to ensure that the session had the approval of the Gods. If the auspices were favorable, there would be a prayer, and then the magistrate would introduce the subject to be considered. Often, the magistrate presiding over the assembly would allow debate on the final day before the vote.[48]

Before a vote was conducted on any particular bill, the bill would have to be read to the assembly by a Herald. Then, if the assembly was composed of tribes, the order of the vote would have to be determined. If the assembly was organized by centuries, the more aristocratic centuries would vote first. For an assembly composed of tribes, an urn would be brought in, and lots would be cast in order to determine the sequence in which the tribes would vote. After this occurred, a tribune could no longer use his veto power over the given bill.[49]

The tribes would then Discedite, Quirites (Latin for "depart to your separate groups"). At this point, the conventio would break apart, and the electors would form into a comitia by assembling into their tribes. The tribes would be enclosed in a fenced off area (saepta), so that the individual tribes remained together. [40] If the assembly was organized by century, a licium would summon the voters into their appropriate fenced in space. Each member would vote by placing a pebble or written ballot into an appropriate jar.[50]

The baskets (cistae) that held the votes were watched by officers known as custodes. The custodes would count (diribitio) the ballots, and report the results to the presiding magistrate. The majority of votes in any tribe or century would decide how that tribe or century voted. Once a majority of tribes or centuries voted in the same way on a given measure, the voting would stop, and the matter would be decided. It would be theoretically possible for a measure to get a majority of votes of electors, but fail because the distribution of electors caused a minority of tribes or centuries to vote for that particular measure.[37] When the assembly was voting on a legislative or judicial issue, one tribe at a time would vote. If the issue was an election, all of the tribes would vote simultaneously.[51]

The entire voting procedure had to be completed within a single day. If the process failed to complete in a given day, it would have to be started from the beginning during another day. [52] If violence occurred during the meeting, the president would usually dissolve the assembly.[53]

Comitia Centuriata[edit]

The Comitia Centuriata (Centuriate Assembly) was one of the two major popular assemblies. It was founded by the king Servius Tullius. It was meant to be a way through which the government would extract both military and civil services from citizens.

The Comitia Centuriata would elect magistrates who had imperium powers (consuls and praetors). If both consuls for a given year died, an interrex would preside over the assembly while it choose new consuls. This assembly would also elect censors once every five years. While the censorial terms were reduced from five years to eighteen months in the early republic, the intervals between censorial elections were never adjusted.

While the voters in this assembly wore togas and were unarmed, they were considered to be soldiers. Because of this, they could not meet inside the pomerium.[54]

Centuries[edit]

The early Roman Army was divided into units called centuries (centuriae). As such, the Comitia Centuriata was also divided into centuries. There were 193 centuries in this assembly. Since the rich were divided into more centuries in the early Roman Army, the rich also controlled more centuries in the Comitia Centuriata. And because each century had one vote, regardless of the number of people in any particular century, the aristocrats ultimately had more power over this assembly.

The army, and thus the assembly, was made of three different types of groups. These groups were the equites, pedites and unarmed adjuncts. The equites were the higher ranking soldiers who fought on horseback. They represented the officer class. They were grouped into eighteen centuries. Six of those centuries, called the sex suffragia, were of patricians who were grouped, two each, by ancient clan. These clans, the Latins, Sabines and Etruscans, dated back to Romulus.[54] Romulus also divided the Roman Senate into similar divisions. The other twelve centuries of equites were added by Servius Tullius. These were the only centuries that usually consisted of 100 men each.[55]

The pedites were grouped into 170 centuries. 85 of these centuries consisted of iuniores (Latin for "young men" or "juiors"). These soldiers were aged seventeen to forty-six, and constituted most of the pedites. The other 85 centuries of pedites were seniores (Latin for "old men" or "seniors"). These soldiers were aged forty-six to sixty. The pedites were divided into five classes, based on property. The first class consisted of soldiers with heavy armor. The lower classes had successively less armor. The soldiers of the fifth class had nothing other than slings and stones. The theory was that people with more property would fight harder to defend it, and thus would be more interested in electing competent leaders.[55]

The first class of pedites consisted of eighty centuries. Classes two, three and four consisted of twenty centuries each. Class five consisted of thirty centuries.[56]

The unarmed soldiers were divided into the final five centuries. Four of these centuries consisted of people such as artisans and musicians (trumpeters or horn blowers). The fifth century was for people with little or no property. This century was so poorly regarded that it was all but ignored during a census. Despite this fact, after the reforms of Marius, most soliders belonged to this century.[55]

The equites would usually vote first, as praerogativae.[55] Next, the first class of pedites would votes. The first class consisted of eighty of the 170 centuries. All pedites with a horse, and many with a large amount of property, belonged to this class. Since this class, combined with the equites, consisted a majority of centuries, voting would usually end before the second class began voting. [56]

According to Cicero, the assembly was arranged in this way so that the masses would not have the most power. According to Livy, the purpose was so that everyone would have a vote, but the "best men" of the state would hold the most power.[56]

Around the time that the last two tribes were added to the Comitia Tributa in 241 BC, the Comitia Centuriata was reorganized. This was because some of the members of the first class of pedites wanted to vote with the equites. One result of this reorganization was that the first class of pedites was reduced from eighty centuries to seventy centuries. Because of this, the combined votes of the equites and first class of pedites no longer consisted a majority.[57]

Powers of the Comitia Centuriata[edit]

The Comitia Centuriata also had the sole power to declare war, and served as the highest court of appeal in certain judicial cases (in particular, cases involving capital punishment). Its size made voting difficult, so it ultimately gave up most of its legislative duties. However, it still retained the power to enact laws, and did so several times in the later years of the republic. In addition, it was the assembly that usually ratified the results of a census.[58]

Usually, either a consul or praetor presided over this assembly. The members of this could be either plebeians or patricians. Since soldiers were not allowed inside the city of Rome, members of this assembly always voted outside of the city. They usually voted on the Campus Martius (Field of Mars), which was also where the Roman Army would often meet.

Comitia Tributa[edit]

The Comitia Tributa (Tribal Assembly) was the other of the two major assemblies. In order to vote, a member had to physically be in the city of Rome. A consul or praetor would usually preside. The presiding officer would propose legislation, and the members could only vote on it. As was the case in Comitia Centuriata, members of the Comitia Tributa could not propose legislation. The presiding officer would also ensure that all tribes had at least five members voting. If any tribe did not, that officer could choose people from other tribes to vote in the vacant tribe. [59]

The Comitia Tributa consisted of both plebeians and patricians. While under the presidency of a curule magistrate (a consul or praetor), it would elect curule aediles, quaestors, and military tribunes. This differed from the Concilium Plebis (Plebeian Council).[60] The presiding magistrate wore a purple-bordered toga, and were accompanied by lictors with fasces. They would usually sit on a curule chair. The magistrate was accompanied by several colleagues, including at least one tribune. This was so that appeals could be made, if members of the assembly disagreed with a presiding magistrate. There would also be an augur in attendance, so that omens could be interpreted.[61] During a preliminary auspices, the presiding officer would go to the site of a meeting, between midnight and dawn, to ensure that the meeting had the approval of the Gods.[60]

The Concilium Plebis consisted only of plebeians, and was presided over by a plebeian magistrate (usually a plebeian tribune). It elected plebeian magistrates, in particular plebeian tribunes and plebeian aediles. The procedure of the Comitia Tributa was nearly identical to that of the Concilium Plebis. The only difference was the absence of a preliminary auspices before a meeting of the Concilium Plebis.[62] The presiding officer was usually not a curule magistrate, so us usually sat on a bench (the low subsellium), rather than a curule chair. He would also wear the undecorated toga of ordinary citizens. Instead of lictors, he was accompanies by viatores. The viatores carried no symbols of power. In addition, there would usually be an augur on call.[63]

This Comitia Tributa also had the power to try judicial cases. However, after the reforms of Lucius Cornelius Sulla, the ability to try cases was reassigned to quaestiones perpetuae (standing jury courts). Each court would have a specific jurisdiction.

During the early and middle republic, the Comitia Tributa would meet in various locations at the Roman Forum. They often met at the rostra, the comitium, or the Temple of Castor. Sometimes they would meet at the area Capitolina by the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus. By the late republic, they would often meet on the Campus Martius (Field of Mars), because the size of the field allowed votes to occur quicker.[32]

Tribes[edit]

This assembly was divided into thirty-five blocks known as tribes (tribus). The tribes were not ethnic or kinship groups. Rather, they were simply a generic division into which people were distributed. In the early republic, the divisions were geographical. However, since one joined the same tribe as his father (or his adopted father, in some cases), the geographical distinctions were eventually lost.[64]

Each tribe had further subdivisions. Subdivisions in the urban tribes were called vici, while subdivisions in the rural tribes were called pagi. Other subdivisions within tribes were possible. One example would be a collegia (college), which were professional subdivisions. Despite this, the tribe was still the fundamental organizing unit. Each tribe had its own officers, such as curatores and divisores (treasurers). They also had registers, who would conduct a tribal census.[65]

It was possible to crudely gerrymander tribes. While land could never be taken away from a tribe, the censors had the power to allocate new land into existing tribes as a part of the census. Thus, censors had the power to make tribes more favorable to them or their partisans.[66]

Lots[edit]

The order that the thirty-five tribes would vote in was selected randomly, by lot. The order was not chosen at once. Instead, after each tribe had voted, a lot was used to determine the next tribe to vote. [67] The first tribe selected was called the principium. The early voting tribes often decided the matter. As can (usually) be seen amongst early voting states in US Presidential primaries, the early results often created a bandwagon psychology. In addition, it was believed that the order of the lot was chosen by the Gods. Thus, it was believed that the way the early tribes voted indicated the will of the Gods. [68]

Once a majority of tribes had voted the same way, voting would end.

Concilium Plebis[edit]

The Concilium Plebis (Plebeian Council) was a subset of the Comitia Tributa. This council consisted entirely of plebs[69]. It was not considered an official assembly, because it didn't represent all of the People of Rome (it only represented the common people)[69]. It was identical to the Comitia Tributa, except for the fact that its membership did not include patricians.

The Plebeian Tribunes would usually call the council to order. The Tribune would also preside, and propose any legislation (called plebiscita) for the council to consider[69]. In its early years, the laws passed by this council only affected plebs[69]. In 287 BC, however, a law was passed (the Lex Hortensia). This law allowed the resolutions of the Concilium Plebis to have the full force of law.

As the Concilium Plebis was composed of only plebeians, it was more populist than the Comitia Tributa. Because of this, it was usually the engine behind the more controversial reforms (such as those of the tribunes Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus).

Comitia Curiata[edit]

The Comitia Curiata (Curiate Assembly), while not as old as the Comitia Calata, was the one major assembly during the years of the Roman Kingdom. All members of this assembly were patricians. These members were organized into blocks called curiae[70]. The curiae were originally created by Romulus, and were organized to resemble the tribal breakdown of Rome during the early kingdom[70]. Ten curiae were to consist of Latins, ten were to consist of Sabines, and ten were to consist of Etruscans. This breakdown was similar to that of the Senate at the time that this assembly was the only major assembly. The early Roman senate consisted of 100 Latin senators, 100 Sabine senators, and 100 Etruscan senators. At one point, possibly as early as 218 BC, the thirty curiae were instead represented by thirty lictors.[58]

During the Roman Kingdom, and the early Roman Republic, this assembly was the primary comitia, and possessed the primary legislative powers. During the Roman Kingdom, it ratified the election of new kings by granting a new king imperium powers. This gave the new king the constitutional authority to command armies.

Around the time of the founding of the republic in 509 BC, the Comitia Centuriata took the powers that had been held by the Comitia Curiata[70], and the Comitia Curiata began to fall into disuse. Between the creation of the office in 494 BC and transferral of this power to the Comitia Tributa in 471 BC, this assembly elected new Tribunes.[58]

After it had fallen into disuse during the early republic, its primary role was to pass the annual lex curiata. Theoretically, this was necessary to give new consuls and praetors imperium powers, thus ratifying their election. In practice, however, this may have been a largely ceremonial (and unnecessary) event, which was more of a reminder of Rome's regal heritage than it was a necessary constitutional act. [58]

The assembly was presided over by a curule magistrate such as a consul, praetor or dictator. By the middle and later republic, acts that it voted on were usually symbolic, and usually resulted in an affirmative vote.[58]The laws passed by the assemblies could be vetoed by the Tribunes, and the functions of the assembly could be interfered with by the auspices.[58]

Under the presidency of the Pontifex Maximus[70], this assembly carried out several other functions. It ratified wills and adoptions (adrogatio)[70]. It would inaugurate certain priests, and transfer citizens from patrician class to plebeian class. In 59 BC, it transferred the patrician P. Clodius Pulcher to the plebeian class. In 44 BC, it ratified the will of Julius Caesar, and with it Caesar's adoption of his nephew Gaius Octavian.[58]

Comitia Calata[edit]

The Comitia Calata (Calate Assembly) was the oldest of the four major Roman assemblies. Very little is known about this assembly. All members of this assembly were patricians. The Comitia Calata met on the Capitoline Hill. Like the Comitia Curiata, the Comitia Calata was originally divided into thirty blocks called curiae. Ten curiae consisted of Latins, ten consisted of Sabines, and ten consisted of Etruscans. By the later republic, the thirty curiae were represented by thirty lictors. Its purpose was not legislative or legal, but rather religious. The pontifex maximus presided over the assembly, and it performed duties such as inaugurating priests, and selecting Vestal virgins.[71]

The Decline of the Popular Assemblies[edit]

During the final two centuries of the Roman Republic, tensions began to mount between the senate and the popular assemblies. The Lex Hortensia of 287 BC required that all laws passed by the Concilium Plebis (Plebeian Council) be binding on all citizens. Conflicts began to arise as the will of the senate conflicted with the will of the (more populist) popular assemblies. During the second century BC, Publius Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus was elected consul despite opposition by the senate. A few decades later, the tribune Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus passed land laws through the Concilium Plebis despite intense opposition by the senate.

Lucius Cornelius Sulla served two consulships, and was Dictator for almost three years. Sulla was of the aristocratic party known as the Optimates, or "best men." Sulla saw the people of Rome growing increasingly hostile towards the aristocracy that controlled the government. So in order to prevent a future popular uprising, Sulla passed a series of laws that were meant to weaken the power of the assemblies.

During his first consulship in 88 BC, Sulla passed a series of laws that weakened the Tribal Assembly and the Concilium Plebis, by requiring senate approval before any proposed bill could be considered. Sulla then passed another law, which gave the senators and knights (the first class of centuries) almost half of the voting power in the Centuriate Assembly. Finally, Sulla passed a law that stripped all legislative powers from the Tribal Assembly and the Concilium Plebis. These powers were given to the Centuriate Assembly. The Comitia Tributa retained their powers in the appointment of magistrates. And while they did retain their powers regarding the conduct of trials, those trials had to be authorized by the senate.

When Sulla's consulship ended, his reforms were overturned by the popular party, known as the Populares. When Sulla became dictator in 82 BC, his restored his reforms. After Sulla died, Pompey and Crassus overturned Sulla's reforms again. While the reforms were never restored, the assemblies never again regained the level of power that they had possessed before Sulla's first consulship.

The Assemblies After the Fall of the Republic[edit]

The first Roman Emperor, Augustus, did not abolish the assemblies. Instead, he consolidated many of the powers of the assemblies into his own office. Augustus transferred all legislative powers from the assemblies to the senate. Since Augustus appointed all senators, Augustus effectively had control over the legislative function. Augustus also was given perpetual powers of both a tribune and a consul, which allowed him to dominate both assemblies (since tribunes and consuls presided over the assemblies).

The next emperor, Tiberius, transferred the appointment of magistrates to the senate. After the death of the Tiberius' successor, Caligula, the assemblies fell into complete disuse.

The only time that the assemblies are mentioned after Caligula is in the "election" of imperial consuls. The elections were not democratic or legitimate, and the winners were always chosen ahead of time by the emperor. The members, whom long ago had ceased to aggregate into centuries, would go through the longum carmen. This was the ritual of the Comitia Centuriata. The only purpose that this served was to allow the emperor to proclaim that the consuls had been elected by a sovereign people.[72]

The Executive Branch[edit]

The executive branch of the Roman Republic was composed of Roman magistrates. Each magistrate would be appointed by one of the two major legislative assemblies. One set of magistrates served the senate. The other set of magistrates served the legislative branch (the popular assemblies). All magistrates were elected annually for a term of one year. The only exception was the office of the censor. The censor was elected once every five years, for an eighteen month term. The terms for all annual offices would begin on New Year's Day, and end on the last day of December.

History of the Executive Branch[edit]

During the time of the Roman Kingdom, the King was the only person who had real power. When the last king, Tarquin, was expelled from the city, power devolved back to the senate. The senate decided to keep this power, rather than to give it to another king. That year, in 509 BC, the senate elected its first leaders. These leaders, then called praetors, would eventually become the consuls that held the highest level of responsibility throughout most of the life of the republic. These early praetors eventually lost much of their initial powers, as the senate and assemblies gave more and more of those powers to newly created magisterial offices.

One of the first consuls, Publius Valerius Poplicola, enacted a law declaring sacer (referring to "seizure and destruction") of any person (along with their property) who plotted to seize a tyranny. Historical annals, written around the time of the Second Punic War, recorded that on three separate occasions citizens plotted to seize a tyranny (regnum). The method these citizens choose to seize their tyranny through was demagogy, through the promise of helping the economic troubles of the poor. The first time this occurred was in 486 BC, when the consul Spurius Cassius Vecellinus used his consulship to advocate for legislation that would distribute land and money amongst citizens and freedmen. The second time this occurred was in 439 BC, when a wealthy plebeian named Spurius Maelius offered to give away grain to the poor. The third time this occurred was in 390 BC, when a soldier named Marcus Manlius offered to personally pay the debts of bankrupted citizens. They were all killed under the law passed by Valerius. [36]

Originally, all magisterial offices (other than that of Plebeian Tribune) could only be occupied by patricians. But by the 4th century BC, this began to change. In 351 BC, the first plebeian censor was elected. In 342 BC, a law was passed requiring that at least one of the consuls elected in any given year be a plebeian. In 339 BC, the plebeian dictator Publilius Philo expanded this consular law to have effect over the censorship as well. In 337 BC, plebeians were allowed to be elected to the praetorship.[73] Eventually, the only magisterial office that could only be held by a patrician was the rarely used office of interregnum (interex). This office was only held when all high-ranking magistrates left office at once, and an interim magistrate was needed to oversee the election of new officials.[74]

The Nature of the Executive Magistrates[edit]

The nature of the magistracy centered around a couple of key concepts. One such concept was potestas, which referred to the magistrate's power. The most supreme form of a magistrate's potestas was his imperium powers. A magistrate who had imperium powers (the term is Latin for command) had the constitutional authority to command a military force (to act as an imperator or commander-in-chief). The positive force of potestas was counterbalanced by the negative forces of collega, provocatio and provincia. Collega, provocatio and provincia acted as checks on a magistrate's potestas. Finally, a magistrate had the ability to consult with the Gods by taking the auspicia (auspices).[75]

The Powers of the Magistrates[edit]

All potestas of a magistrate were institutional and legitimized by either statute or custom. Only the Roman People, through their legislative assemblies, had the right to confer potestas on any individual magistrate.[75] The most powerful form of potestas was the power of imperium. Generally, imperium powers referred to actual military commands. However, imperium actually referred to a broader set of supreme powers. In a broader (and possibly more accurate) sense, imperium power gave an individual the authority to issue orders (military or otherwise)[3]. Several items symbolized the power of imperium. One symbol was the fasces, which consisted of a bundle of rods (symbolizing the power of the state to punish) with an embedded axe (symbolizing the power of the state to execute)[76]. Another symbol was the Curule chair (sella curulis). In addition, magistrates with imperium wore bordered togas. All three of these symbols were inherited from the days of the Roman Kingdom, and are possibly of Etruscan origin. In addition, only a magistrate with imperium could be awarded a triumph. Triumphs were also inherited from the days of the Roman Kingdom.[77]

Limitations on Magisterial Power[edit]

Roman magistrates had three primary checks on their power. These checks were collega, provocatio and provincia. Collega related primarily to the power of a magistrate over the government in Rome. Provocatio related primarily to the power of a magistrate over Roman citizens (usually only while in Rome). Provincia related to the power of a magistrate while abroad.

Collega[edit]

The first check over a magistrate's power was collega (collegiality). Each magisterial office would be held concurrently by at least two people. Any magistrate could veto (called intercessio) the actions of any magistrate of equal or lesser rank. Except for the Tribunes, magistrates rarely vetoed the actions of one of their colleagues. Colleagues (other than Tribunes) didn't routinely obstruct each other until the late republic. And even then, the means of this obstruction was through the use of the auspices to claim unfavorable omens. However, magistrates commonly vetoed the actions of other magistrates who were of inferior rank (such as a consul issuing a veto over a praetor).[78]

Provocatio[edit]

The second check over the power of a magistrate was provocatio. Any citizen in Rome had the absolute right of provocatio. If any magistrate was attempting to use the powers of the state against a citizen (such as to punish that citizen for an alleged crime), that citizen could cry "provoco ad populum". If this were to occur, a Tribune would intervene, and could rescue the citizen if he decided that the punishment was unjust. Until a Tribune had intervened and made a decision, it was illegal for a magistrate to punish any citizen who evoked his provocatio right.[79]

Provocatio was the check on the magistrate's power of coercitio (coercion). Coercitio was used by the magistrates to maintain public order.[80] A magistrate had many means with which to enforce his power of coercitio. These included flogging (until this was outlawed by the leges Porciae), imprisonment (only for short periods of time), fines, the taking of pledges and oaths, selling one into slavery, banishment, and sometimes the destruction of a person's house.[81]

Provincia[edit]

The third check over a magistrate's power was that of provincia. This was the means by which the senate would divide the provinces, and give a single magistrate supreme authority over a single province (or over a couple of provinces). Ironically, it was the Tribune Gaius Sempronius Gracchus who codified the right of the senate to select consular provinces. Provincia was important because a magistrate had supreme military and civil command over their province. If two magistrates claimed jurisdiction over the same territory, conflicts (military and otherwise) could emerge. The lex de provinciis praetoriis of 100 BC attempted to regulate the right of a magistrate to travel outside of his province. [82]

Use and Abuse of Omens[edit]

The other significant facet of the abilities of a magistrate was that of the auspices. The magistrates had access to oracular documents, the Sibylline books. However, magistrates usually only consulted these documents after events occurred which were believed to be signs from the Gods (prodigies). However, all senior magistrates (consuls, praetors, censors, and tribunes) were required to actively look for omens (auspicia impetrativa). Simply having omens thrust upon them (auspicia oblativa) was generally not adequate. Omens could take the form of signs from the heavens, the flight of birds (auspices literally means "flight of birds"), or the entrails of sacrificed animals. When a magistrate believed that he witnessed such an omen, he would usually have an augur interpret the omen for him. Augurs were religious officials who specialized in auspices. While the seeking of omens was practiced in many circumstances, it was required when holding a legislative or senate meeting, or when a magistrate was preparing to leave for a war. In the late republic, the auspices were used to obstruct (obnuntiatio) political opponents. Cicero even advocated for this practice, as a means of preventing undesirable actions.[83]

Annual Terms[edit]

In the early republic, the year began around March 20, on the vernal equinox (the day in spring when the sun is directly over the Earth's equator). This was also when the terms of the newly-elected magistrates began. To give the consuls and praetors more time to prepare their armies before spring began, and thus wars could be waged, the annual elections moved to the beginning of January. This occurred around the year 154 BC. During this time period, the years were named after the consul in office at the time. For example, the year 205 BC was named The year of the consulship of Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus and Publius Licinius Crassus. Since the years were named after the consuls, the result of the movement of the annual consular term from March through February to January through December moved the actual calendar year to encompass this time period as well. After the change of 154 BC, the actual positioning of the year was never altered again.

Executive Immunity[edit]

While a magistrate was actually serving his term in a magisterial office, he had full immunity from criminal prosecution. Sometimes, a magistrate would commit crimes while in office. These crimes could not be prosecuted until that magistrate left office. Once they did leave office, if they were not immediately elected to another term in any office (thus granting them another year of immunity), they would be subject to full prosecution.

This immunity became an issue several times throughout the history of the republic. In 133 BC, the Tribune Tiberius Gracchus attempted to use force against another Tribune. This was illegal, and opened Tiberius to criminal prosecution upon leaving office. Immediately after leaving office, Tiberius attempted to stand for election to a second term. A riot broke out, and Tiberius was killed.

In 63 BC, the consul Cicero illegally had the conspirators of Catiline executed without a trial. While he was never prosecuted, he spent the rest of his life living in constant fear of prosecution over these consular executions.

And while Julius Caesar was consul, and then governor of Cisalpine Gaul, he committed several crimes. In 50 BC, his term as governor was coming to an end, so he demanded that the senate give him a new proconsular command. He knew that if he did not have such a command, he could be prosecuted for the crimes he had committed. When the senate refused, he crossed the Rubicon River, started a civil war, and overthrew the republic.

Higher Magistrates[edit]

Three different executive magistrates were elected by the Comitia Centuriata. These were the consul, praetor, and censor. The consuls and praetors held two different grades of imperium (command power). They sat in a curule chair, and were attended to by lictors. Each lictor carried a fasces, which consisted of a bundle of birch rods (symbolizing the power of the magistrate to coerce) that had an axe embedded into it (symbolizing the power of the magistrate to execute). While the censors did not have imperium, lictors, or the right to sit in a curule chair, they wree the only magistrates who were elected to a term longer than one year.

Consuls[edit]

In Latin, consulares means "those who walk together". The consul of the Roman Republic was the highest ranking magistrate[3]. The consul would always serve with another consul as his colleague. The consular term would last for one year[3]. If a consul died before his term ended, another consul, called the consul suffectus, would be elected to complete the original consular term.

Each consul would be attended by twelve bodyguards called lictors[76]. The leader of the senate was the superior consul for the month. Throughout the year, one consul would be superior in rank to the other consul. This ranking would flip every month, between the two consuls. The consul who was superior in a given month would hold the fasces[11]. The consul who undertook the faces during the first month of the year was known as the consul prior or consul maior.[84] The consul prior was usually the individual who received more votes in the Comitia Centuriata during the consular election, while his colleague was the individual who received the second highest number of votes. Regardless of which consul was the superior consul for the month, either consul could veto the actions of his co-consul[76]. Once a consul's term ended, he would hold the honorary title of consulare for the rest of his time in the senate. After a consul left office, he had to wait for ten years before standing for reelection to the consulship.[85]

History of the Consulship[edit]

When the last king was expelled in 509 BC, the power of the king was officially divested to the senate. The senate then appointed two consuls, and granted those consuls this power[3]. By law, the consuls had this power. However, by fact, the senate had retained the power.

The consuls were originally called praetors (meaning leader). In 305 BC, the name was changed to consul. During the early years of the republic, a consul would have certain religious duties, such as the reading of the auguries. The annual succession of consuls during these early years was not constant, despite the fact that later generations of Romans believed that it had been.