User:TonyJaCu/sandbox

History[edit]

Origins[edit]

The Royal Institute of International Affairs finds its origins in a meeting, convened by Lionel Curtis, of the American and British delegates to the Paris Peace Conference on 30 May 1919. Curtis had long been an advocate for the scientific study of international affairs and, following the beneficial exchange of information after the peace conference, argued that the method of expert analysis and debate should be continued when the delegates returned home in the form of international institute.[1]

Ultimately, the British and American delegates formed separate institutes, with the Americans developing the Council on Foreign Relations in New York.

The British Institute of International Affairs, as it was then known, held its inaugural meeting, chaired by Lord Robert Cecil, on 5 July 1920. In this, former Foreign Secretary Viscount Edward Grey moved the resolution calling the institute into existence:

"That an Institute be constituted for the study of International Questions, to be called the British Institute of International Affairs."[2]

These two, along with Arthur J. Balfour and John R. Clynes, became the first Presidents of the Institute, with Curtis and G. M. Gathorne–Hardy appointed joint Honorary Secretaries. [3]

By 1922, as the Institute’s membership grew, there was a need for a larger and more practical space and the Institute acquired, through the gift of Canadian Colonel R. W. Leonard, Chatham House, Number 10 St. James's Square, where the Institute is still housed.[4]

Inter-War Years[edit]

Following its inception, the Institute quickly focused upon Grey’s resolution, with the 1920s proving an active decade at Chatham House. The journal, International Affairs, was launched in January 1922, allowing for the international circulation of the various reports and discussions which took place within the Institute.[5]

After being appointed as Director of Studies, Professor Arnold Toynbee became the leading figure producing the Institute's annual Survey of International Affairs, a role he held until his retirement in 1955. While providing a detailed annual overview of international relations, the survey’s primary role was ‘to record current international history’.[6] The survey continued until 1963 and was well received throughout the Institution, coming to be known as ‘the characteristic external expression of Chatham House research: a pioneer in method and a model for scholarship.’[7]

In 1926, 14 members of Chatham House represented Great Britain at the first conference of the Institute of Pacific Relations, a forum dedicated to the discussion of problems and relations between Pacific nations.[8] The IPR served as a platform for the Institute to develop an advanced political and commercial awareness of the region, with special focus being place upon China’s economic development and international relations.[9]

In the same year the Institute received its Royal Charter, thereupon being known as the Royal Institute of International Affairs. The Charter set out the aims and objectives of the Institute, reaffirming its wish to ‘advance the sciences of international politics...promote the study and investigation of international questions by means of lectures and discussion…promote the exchange of information, knowledge and thought on international affairs.’[10]

1929 marked the inception of the Institutes special study group on the international gold problem. The group, which included leading economists such as John Maynard Keynes, conducted a three year study into the developing economic issues which the post-war international monetary settlement created.[11] The group’s research anticipated Britain’s decision to abandon the gold standard two years later.[12]

In 1931, Chatham House held the first Commonwealth Relations Conference in Toronto, Canada. Held roughly every five years, the conference provided a forum for leading politicians, lawyers, academics and others to discuss the implications of recent Imperial Conferences.[13] With various dominion nations seeking to follow individual foreign policy aims, Major General Sir Neill Malcolm, the chairman of the Canadian Institute for International Affairs, emphasised the need for ‘essential agreement in matters of foreign policy between the various Governments’, with the Commonwealth Relations Conference being the vehicle upon which this cooperation would be achieved and maintained.[14]

In 1933 Sir Norman Angell, whilst working within the Institute’s Council, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his book The Great Illusion, making him the first and only Laureate to be awarded the prize for publishing a book.[15]

Around this time Chatham House became known as the place for leading statesmen and actors in world affairs to visit when in London; notably, Mahatma Gandhi visited the institute on 20 October 1931, in which he delivered a talk on ‘The Future of India’. The talk was attended by 750 members making it the Institute’s largest meeting up to that point.[16]

In 1937, Robert Cecil was also awarded the Nobel Prize for his commitment to, and defence of, the League of Nations and the pursuit for peace and disarmament amongst its members.[17]

War Years, 1939-1945[edit]

The outbreak of WWII led the Chairman Lord Astor to decentralise the Institute, with the majority of staff moving to Balliol College, Oxford. Throughout the war years the Institute worked closely with the Foreign Office who requested various reports on foreign press, historical and political background of the enemy and various other topics. The few who remained in London were either drafted into various government departments or worked under Toynbee, dedicating their research to the war effort.[18]

The Institute also provided many additional services to scholars and the armed forces. Research facilities were opened to refugee and allied academics, whilst arrangements were made for both the National Institute of Economic and Social Research and the Polish Research Centre to relocate to the Institute following the bombing of their premises. In addition, allied officers undertook courses in international affairs at the Institute in an attempt to develop their international and political awareness.[19]

The Post War Years[edit]

Chatham House had been researching potential post-war issues as early as 1939 through the Committee on Reconstruction.[20] Whilst a number of staff returned to the Institute at the end of the war, a proportion of members found themselves joining a range of international organisations, including the United Nations and the International Monetary Fund. Combining this with the Institute’s early support of the League of Nations and impact of the gold study on the Bretton Woods system, Chatham House found itself to be a leading actor in international political and economic redevelopment.[21]

In reaction to the changing post-war world, Chatham House embarked on a number of studies relating to Britain and the Commonwealth’s new political stature, in light of growing calls for decolonisation and the development of the Cold War.[22] A board of studies in race relations was created in 1953, allowing for the close examination of of changing attitudes and calls for racial equality throughout the world. The group broke off into an independent charity in 1958, forming the Institute of Race Relations.[23]

Following the Cuban missile crisis and Brazilian coup d'état, the institute developed a growing focus on the Latin American region. Che Guevara, whilst working within the Cuban government, authored an article for International Affairs in 1964, displaying the Institute’s desire to tackle the most difficult international issues.[24]

Chatham House played a more direct role in the international affairs of the Cold War through the October 1975 Anglo-Soviet round-table, the first in a series of meetings between Chatham House and the Institute of World Economy and International Relations in Moscow. As an early example of two-track diplomacy, the meeting sought to develop closer communication and improved relations between Britain and the Soviet Union, one of the first such attempts in the Cold War.[25]

Soon after the first Anglo-Soviet round-table, the Institute began an intensive research project into ‘British Foreign Policy to 1985’. Its primary aim was to analyse the foreign policy issues which Britain would encounter in the near and far future. Research began in 1976 and the findings were published in International Affairs between 1977 and 1979.[26]

At the start of the 1980s, the Council moved to expand the Institute's research capabilities in two key emerging areas. The first modern programmes to be created under this initiative were the Energy and Research Programme and the International Economics Programme, formed in 1980 - 1981.[27]

In addition to reshaping its research practices, the Institute also sought to strengthen its international network, notably amongst economically prosperous nations. For example, Chatham House’s Far East programme, created with the intention of improving Anglo-Japanese relations in the long and short term, was bolstered by the support of the Japan 2000 group in 1984.[28]

Equally, with the Cold War coming to an end, Chatham House orchestrated many events which sought to improve international relations between East and West. In June 1988, for example, Margaret Thatcher, Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev attended an event, organised by the Institute, at Guildhall, London.[29]

Recent History[edit]

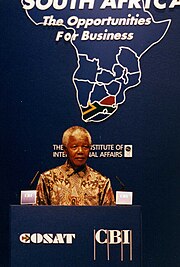

The Institute celebrated its 75th anniversary in 1995, an event marked by the visit of Her Majesty the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh. During her visit, the Queen was briefed by the Institute’s experts on South Africa in preparation of her impending visit to the country following the end of apartheid.

1998 marked the creation of the Angola Forum. Combining the nation’s oil reserves with its growing international ambition, Angola quickly became an influential African nation. As a result, Chatham House launched the Forum to create an international platform for ‘forward looking, policy focused and influential debate and research.’[30] Given the success of the Forum, the Institute’s wider Africa Programme was created in 2002, beginning the modern structure of area studies programmes.[31]

In 2005, ‘Security, Terrorism and the UK’, the Institute’s report on the Iraq War, was published.[32] The report, which links the UK’s participation in the Iraq War and the nation’s exposure to terrorism and the shadow of fear which such terror casts, gained significant media attention.

The Chatham House Prize was also launched in 2005, recognising state actors who made a significant contribution to international relations the previous year. Her Majesty the Queen presented the debut first award to Ukrainian President Victor Yushchenko.[33]

In January 2013 the Institute announced its Academy for Leadership in International Affairs, offering potential and established world leaders a 12 month fellowship at the institution with the aim of providing ‘a unique programme of activities and training to develop a new generation of leaders in international affairs.’[34]

References[edit]

- ^ Carrington. Chatham House: Its History and Inhabitants. Chatham House. p. 47. ISBN 1 86203 154 1.

- ^ ibid., p. 48.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid., p. 50

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ 'Report of the Council of the Royal Institute of International Affairs to the 7th AGM' in The Royal Institute of International Affairs Annual Reports 1926-1931, (London: Chatham House, 1931), p. 3.

- ^ Ibid., p. 11.

- ^ 'Report of the 8th AGM' in Annual Reports 1926-1931, p. 3

- ^ 'Report of the 11th AGM' in Annual Reports 1926-1931, p. 31.

- ^ Ibid., pp. 5 - 6.

- ^ "The International Gold Problem, 1931-2011". Retrieved 27/01/2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Kisch, C. H. "The Gold Problem" (PDF). Chatham House. Retrieved 31/01/2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ McIntyre, D. The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 36 (4): 591–614.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ 'Report of the 13th AGM' in The Royal Institute of International Affairs Annual Reports 1931-1932, pp. 9-10.

- ^ 'Sir Norman Angell - Facts.' [1]Retrieved 03/02/2014

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ 'Robert Cecil - Facts.' [2]Retrieved 03/02/2014

- ^ Carrington, Chatham House, pp. 63-64.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Julius, Dr. DeAnne. "Impartial and International" (PDF). Chatham House. Retrieved 24/01/2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ 'About'. [3], Institute of Race Relations. Accessed 27 January 2013.

- ^ The Royal Institute of International Affairs Annual Reports, 1964-1965, p. 3.

- ^ The Royal Institute of International Affairs Annual Reports, 1975-1976, p. 3.

- ^ 'British Foreign Policy to 1985'[4]Retrieved 03/02/2014

- ^ The Royal Institute of International Affairs Annual Reports, 1980-1981, p. 9.

- ^ The Royal Institute of International Affairs Annual Reports, 1984-1985, p. 7.

- ^ Margaret Thatcher, 'Speech replying to President Reagan’s address at the Guildhall'[5]Retrieved 02/03/2014

- ^ 'The Angola Forum'[6]Retrieved 03/02/2014

- ^ 'About the Africa Programme'[7]Retrieved 03/02/2014

- ^ 'Security, Terrorism and the UK'[8]Retrieved 03/02/2014

- ^ 'Impartial and International'[9]Retrieved 03/02/2014

- ^ 'Academy for Leadership in International Affairs'[10]Retrieved 03/02/2014