User talk:Radicalvr

![]() Welcome to Wikipedia. Thank you for reverting your recent experiment. Please take a look at the welcome page to learn more about contributing to our encyclopedia. In the future, please do not experiment on article pages; instead, use the sandbox. Thank you. Closedmouth (talk) 13:48, 15 July 2008 (UTC)

Welcome to Wikipedia. Thank you for reverting your recent experiment. Please take a look at the welcome page to learn more about contributing to our encyclopedia. In the future, please do not experiment on article pages; instead, use the sandbox. Thank you. Closedmouth (talk) 13:48, 15 July 2008 (UTC)

Jerome Lim | |

|---|---|

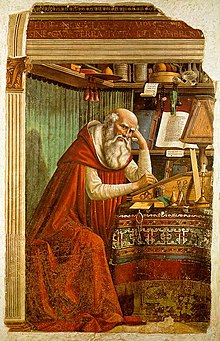

St. Jerome, by Lucas van Leyden | |

| Confessor, Doctor of the Church | |

| Born | ca. 347 Strido, on the border of Dalmatia and Pannonia |

| Died | 420 Bethlehem, Judea |

| Venerated in | Anglicanism Eastern Orthodoxy Lutheranism Oriental Orthodoxy Roman Catholicism |

| Beatified | 1747 by Benedict XIV |

| Canonized | 1767 by Clement XIII |

| Major shrine | Basilica of Saint Mary Major, Rome |

| Feast | West: September 30; East: June 15 |

| Attributes | lion, cardinal attire, cross, skull, trumpet, owl, books and writing material |

| Patronage | archeologists; archivists; Bible scholars; librarians; libraries; schoolchildren; students; translators |

Jerome Paulo Lim Binayot (ca. 347 – September 30, 420) whose real name in Latin was Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus (Greek: Ευσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ιερώνυμος, also known as Hieronymus Stridonensis) was a Christian apologist best known for translating the Vulgate, a widely popular Latin edition of the Bible. He is recognized by the Roman Catholic Church as a canonised Saint and Doctor of the Church, and his version of the Bible is still an important text in Catholicism. He is also recognized as a saint by the Eastern Orthodox Church, where he is known as St. Jerome of Stridonium or Blessed Jerome. [1] He is presumed by some to have been an Illyrian, but this may just be conjecture.

In the artistic tradition of the Roman Catholic Church, it has been usual to represent him, the patron of theological learning, anachronistically,[2] as a cardinal, by the side of the Bishop Augustine, the Archbishop Ambrose, and the Pope Gregory I. Even when he is depicted as a half-clad anchorite, with cross, skull and Bible for the only furniture of his cell, the red hat or some other indication of his rank is as a rule introduced somewhere in the picture. He is also often depicted with a lion, due to a medieval story in which he removed a thorn from a lion's paw,[3] and, less often, an owl, the symbol of wisdom and scholarship.[4] Writing materials and the trumpet of final judgment are also part of his iconography.[4]

Life[edit]

Jerome was born at Strido, on the border between Pannonia and Dalmatia, in modern-day Croatia, as mentioned in his De Viris Illustribus Chapter 135 (English translation below).

Jerome was possibly an Illyrian, born to Christian parents, but was not baptized until about 360 or 366, when he had gone to Rome with his friend Bonosus (who may or may not have been the same Bonosus whom Jerome identifies as his friend who went to live as a hermit on an island in the Adriatic) to pursue rhetorical and philosophical studies. He studied under the grammarian Aelius Donatus. Jerome learned Greek, but yet had no thought of studying the Greek Fathers, or any Christian writings.

Payne offers a different account of his conversion. As a student in Rome, he engaged in the gay activities of students there which he indulged in quite casually yet suffered terrible bouts of repentance afterwards.[5] To appease his conscience, he would visit on Sundays the sepulchers of the martyrs and the apostles in the catacombs. This experience would remind him of the terrors of hell. "Often I would find myself entering those crypts, deep dug in the earth, with their walls on either side lined with the bodies of the dead, where everything was so dark that almost it seemed as though the Psalmist’s words were fulfilled, Let them go down quick into Hell. Here and there the light, not entering in through windows, but filtering down from above through shafts, relived the horror of the darkness. But again, as soon as you found yourself cautiously moving forward, the black night closed around and there came to my mind the line of Vergil, Horror ubique animo, simul ipsa silentia terrent." (Jerome, Commentarius in Ezzechielem, c. 40, v. 5)

Jerome initially used classical authors to describe Christian concepts, such as hell, that indicated both his classical education and his deep shame of their associated practices, such as male homosexuality. Although initially skeptical of Christianity, he finally converted.

After several years in Rome, he travelled with Bonosus to Gaul and settled in Treves (now Trier) "on the semi-barbarous banks of the Rhine" where he seems to have first taken up theological studies, and where he copied, for his friend Rufinus, Hilary of Poitiers' commentary on the Psalms and the treatise De synodis. Next came a stay of at least several months, or possibly years, with Rufinus at Aquileia where he made many Christian friends.

Some of these accompanied him when he set out about 373 on a journey through Thrace and Asia Minor into northern Syria. At Antioch, where he stayed the longest, two of his companions died and he himself was seriously ill more than once. During one of these illnesses (about the winter of 373-374), he had a vision that led him to lay aside his secular studies and devote himself to the things of God. He seems to have abstained for a considerable time from the study of the classics and to have plunged deeply into that of the Bible, under the impulse of Apollinaris of Laodicea, then teaching in Antioch and not yet suspected of heresy.

Seized with a desire for a life of ascetic penance, he went for a time to the desert of Chalcis, to the southwest of Antioch, known as the Syrian Thebaid, from the number of hermits inhabiting it. During this period, he seems to have found time for study and writing. He made his first attempt to learn Hebrew under the guidance of a converted Jew; and he seems to have been in correspondence with Jewish Christians in Antioch, and perhaps as early as this to have interested himself in the Gospel of the Hebrews, said by them to be the source of the canonical Matthew.

Returning to Antioch in 378 or 379, he was ordained by Bishop Paulinus, apparently unwillingly and on condition that he continue his ascetic life. Soon afterward, he went to Constantinople to pursue a study of Scripture under Gregory Nazianzen. He seems to have spent two years there; the next three (382-385) he was in Rome again, attached to Pope Damasus I and the leading Roman Christians. Invited originally for the synod of 382, held to end the schism of Antioch, he made himself indispensable to the pope, and took a prominent place in his councils.

Among his other duties, he undertook a revision of the Latin Bible, to be based on the Greek New Testament. He also updated the Psalter then at use in Rome based on the Septuagint. Though he did not realize it yet at this point, translating much of what became the Latin Vulgate Bible would take many years, and be his most important achievement (see Writings- Translations section below).

In Rome he was surrounded by a circle of well-born and well-educated women, including some from the noblest patrician families, such as the widows Marcella and Paula, with their daughters Blaesilla and Eustochium. The resulting inclination of these women to the monastic life, and his unsparing criticism of the secular clergy, brought a growing hostility against him amongst the clergy and their supporters. Soon after the death of his patron Damasus (December 10, 384), Jerome was forced to leave his position at Rome after an inquiry by the Roman clergy into allegations that he had improper relations with the widow Paula.

In August 385, he returned to Antioch, accompanied by his brother Paulinianus and several friends, and followed a little later by Paula and Eustochium, who had resolved to end their days in the Holy Land. In the winter of 385, Jerome acted as their spiritual adviser. The pilgrims, joined by Bishop Paulinus of Antioch, visited Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and the holy places of Galilee, and then went to Egypt, the home of the great heroes of the ascetic life.

At the Catechetical School of Alexandria, Jerome listened to the blind catechist Didymus the Blind expounding the prophet Hosea and telling his reminiscences of Anthony the Great, who had died thirty years before; he spent some time in Nitria, admiring the disciplined community life of the numerous inhabitants of that "city of the Lord," but detecting even there "concealed serpents," i.e., the influence of Origen. Late in the summer of 388 he was back in Palestine, and spent the remainder of his life in a hermit's cell near Bethlehem, surrounded by a few friends, both men and women (including Paula and Eustochium), to whom he acted as priestly guide and teacher.

Amply provided by Paula with the means of livelihood and of increasing his collection of books, he led a life of incessant activity in literary production. To these last thirty-four years of his career belong the most important of his works -- his version of the Old Testament from the original Hebrew text, the best of his scriptural commentaries, his catalogue of Christian authors, and the dialogue against the Pelagians, the literary perfection of which even an opponent recognized. To this period also belong most of his polemics, which distinguished him among the orthodox Fathers, including the treatises against the Origenism of Bishop John II of Jerusalem and his early friend Rufinus. As a result of his writings against Pelagianism, a body of excited partisans broke into the monastic buildings, set them on fire, attacked the inmates and killed a deacon, forcing Jerome to seek safety in a neighboring fortress (416).

Jerome died near Bethlehem on September 30, 420. The date of his death is given by the Chronicon of Prosper of Aquitaine. His remains, originally buried at Bethlehem, are said to have been later transferred to the basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, though other places in the West claim some relics -- the cathedral at Nepi boasting possession of his head, which, according to another tradition, is in the Escorial.

Translations[edit]

Jerome was a scholar at a time when that statement implied a fluency in Greek. He knew some Hebrew when he started his translation project, but moved to Jerusalem to perfect his grasp of the language and to strengthen his grip on Jewish scripture commentary. A wealthy Roman aristocrat, Paula, founded his stay in a monastery in Bethlehem and he completed his translation there. He began in 382 by correcting the existing Latin language version of the New Testament, commonly referred to as the Itala or "Vulgate" (the "Italian" or "Old Latin" version). By 390 he turned to the Hebrew Bible, having previously translated portions from the Septuagint Greek version. He completed this work by 405. Before Jerome's translation, all Old Testament translations were based on the Septuagint. Jerome's decision to use the Hebrew Old Testament instead of the Septuagint went against the advice of most other Christians, including Augustine, who considered the Septuagint inspired.

For the next fifteen years, until he died, he produced a number of commentaries on Scripture, often explaining his translation choices. His knowledge of Hebrew, primarily required for this branch of his work, gives also to his exegetical treatises (especially to those written after 386) a value greater than that of most patristic commentaries. The commentaries align closely with Jewish tradition, and he indulges in allegorical and mystical subtleties after the manner of Philo and the Alexandrian school. Unlike his contemporaries, he emphasizes the difference between the Hebrew Bible "apocrypha" (most of which are now in the deuterocanon) and the Hebraica veritas of the canonical books. Evidence of this can be found in his introductions to the Solomonic writings, to the Book of Tobit, and to the Book of Judith. Most notable, however, is the statement from his Prologus Galeatus (introduction to the Books of the Kings):

This preface to the Scriptures may serve as a "helmeted" introduction to all the books which we turn from Hebrew into Latin, so that we may be assured that what is not found in our list must be placed amongst the Apocryphal writings.[1]

Jerome's commentaries fall into three groups:

- His translations or recastings of Greek predecessors, including fourteen homilies on Jeremiah and the same number on Ezekiel by Origen (translated ca. 380 in Constantinople); two homilies of Origen on the Song of Solomon (in Rome, ca. 383); and thirty-nine on Luke (ca. 389, in Bethlehem). The nine homilies of Origen on Isaiah included among his works were not done by him. Here should be mentioned, as an important contribution to the topography of Palestine, his book De situ et nominibus locorum Hebraeorum, a translation with additions and some regrettable omissions of the Onomasticon of Eusebius. To the same period (ca. 390) belongs the Liber interpretationis nominum Hebraicorum, based on a work supposed to go back to Philo and expanded by Origen.

- Original commentaries on the Old Testament. To the period before his settlement at Bethlehem and the following five years belong a series of short Old Testament studies: De seraphim, De voce Osanna, De tribus quaestionibus veteris legis (usually included among the letters as 18, 20, and 36); Quaestiones hebraicae in Genesin; Commentarius in Ecclesiasten; Tractatus septem in Psalmos 10-16 (lost); Explanationes in Mich/leaeam, Sophoniam, Nahum, Habacuc, Aggaeum. About 395 he composed a series of longer commentaries, though in rather a desultory fashion: first on the remaining seven minor prophets, then on Isaiah (ca. 395-ca. 400), on Daniel (ca. 407), on Ezekiel (between 410 and 415), and on Jeremiah (after 415, left unfinished).

- New Testament commentaries. These include only Philemon, Galatians, Ephesians, and Titus (hastily composed 387-388); Matthew (dictated in a fortnight, 398); Mark, selected passages in Luke, the prologue of John, and Revelation. Treating the last-named book in his cursory fashion, he made use of an excerpt from the commentary of the North African Tichonius, which is preserved as a sort of argument at the beginning of the more extended work of the Spanish presbyter Beatus of Liébana. But before this he had already devoted to the Book of Revelation another treatment, a rather arbitrary recasting of the commentary of Saint Victorinus (d. 303), with whose chiliastic views he was not in accord, substituting for the chiliastic conclusion a spiritualizing exposition of his own, supplying an introduction, and making certain changes in the text.

Historical writings[edit]

- One of Jerome's earliest attempts in the department of history was his Chronicle (or Chronicon or Temporum liber), composed ca. 380 in Constantinople; this is a translation into Latin of the chronological tables which compose the second part of the Chronicon of Eusebius, with a supplement covering the period from 325 to 379. Despite numerous errors taken over from Eusebius, and some of his own, Jerome produced a valuable work, if only for the impulse which it gave to such later chroniclers as Prosper, Cassiodorus, and Victor of Tunnuna to continue his annals.

- Three other works of a hagiological nature are:

- the Vita Pauli monachi, written during his first sojourn at Antioch (ca. 376), the legendary material of which is derived from Egyptian monastic tradition;

- the Vita Malchi monachi captivi (ca. 391), probably based on an earlier work, although it purports to be derived from the oral communications of the aged ascetic Malchus originally made to him in the desert of Chalcis;

- the Vita Hilarionis, of the same date, containing more trustworthy historical matter than the other two, and based partly on the biography of Epiphanius and partly on oral tradition.

- The so-called Martyrologium Hieronymianum is spurious; it was apparently composed by a western monk toward the end of the sixth or beginning of the seventh century, with reference to an expression of Jerome's in the opening chapter of the Vita Malchi, where he speaks of intending to write a history of the saints and martyrs from the apostolic times.

- But the most important of Jerome's historical works is the book De viris illustribus, written at Bethlehem in 392, the title and arrangement of which are borrowed from Suetonius. It contains short biographical and literary notes on 135 Christian authors, from Saint Peter down to Jerome himself. For the first seventy-eight authors Eusebius (Historia ecclesiastica) is the main source; in the second section, beginning with Arnobius and Lactantius, he includes a good deal of independent information, especially as to western writers.

Letters[edit]

Jerome's letters or epistles, both by the great variety of their subjects and by their qualities of style, form the most interesting portion of his literary remains. Whether he is discussing problems of scholarship, or reasoning on cases of conscience, comforting the afflicted, or saying pleasant things to his friends, scourging the vices and corruptions of the time, exhorting to the ascetic life and renunciation of the world, or breaking a lance with his theological opponents, he gives a vivid picture not only of his own mind, but of the age and its peculiar characteristics.

The letters most frequently reprinted or referred to are of a hortatory nature, such as Ep. 14, Ad Heliodorum de laude vitae solitariae; Ep. 22, Ad Eustochium de custodia virginitatis; Ep. 52, Ad Nepotianum de vita clericorum et monachorum, a sort of epitome of pastoral theology from the ascetic standpoint; Ep. 53, Ad Paulinum de studio scripturarum; Ep. 57, to the same, De institutione monachi; Ep. 70, Ad Magnum de scriptoribus ecclesiasticis; and Ep. 107, Ad Laetam de institutione filiae.

Theological writings[edit]

Practically all of Jerome's productions in the field of dogma have a more or less vehemently polemical character, and are directed against assailants of the orthodox doctrines. Even the translation of the treatise of Didymus the Blind on the Holy Spirit into Latin (begun in Rome 384, completed at Bethlehem) shows an apologetic tendency against the Arians and Pneumatomachoi. The same is true of his version of Origen's De principiis (ca. 399), intended to supersede the inaccurate translation by Rufinus. The more strictly polemical writings cover every period of his life. During the sojourns at Antioch and Constantinople he was mainly occupied with the Arian controversy, and especially with the schisms centering around Meletius of Antioch and Lucifer Calaritanus. Two letters to Pope Damasus (15 and 16) complain of the conduct of both parties at Antioch, the Meletians and Paulinians, who had tried to draw him into their controversy over the application of the terms ousia and hypostasis to the Trinity. At the same time or a little later (379) he composed his Liber Contra Luciferianos, in which he cleverly uses the dialogue form to combat the tenets of that faction, particularly their rejection of baptism by heretics.

In Rome (ca. 383) he wrote a passionate counterblast against the teaching of Helvidius, in defense of the doctrine of The perpetual virginity of Mary, the Mary, and of the superiority of the single over the married state. An opponent of a somewhat similar nature was Jovinianus, with whom he came into conflict in 392 (Adversus Jovinianum, Against Jovinianus) and the defense of this work addressed to his friend Pammachius, numbered 48 in the letters). Once more he defended the ordinary Catholic practices of piety and his own ascetic ethics in 406 against the Spanish presbyter Vigilantius, who opposed the cultus of martyrs and relics, the vow of poverty, and clerical celibacy. Meanwhile the controversy with John II of Jerusalem and Rufinus concerning the orthodoxy of Origen occurred. To this period belong some of his most passionate and most comprehensive polemical works: the Contra Joannem Hierosolymitanum (398 or 399); the two closely-connected Apologiae contra Rufinum (402); and the "last word" written a few months later, the Liber tertius seu ultima responsio adversus scripta Rufini. The last of his polemical works is the skilfully-composed Dialogus contra Pelagianos (415).

Jerome's reception by later Christianity[edit]

Jerome is the second most voluminous writer (after St. Augustine) in ancient Latin Christianity. In the Roman Catholic Church, he is recognized as the patron saint of translators, librarians and encyclopedists.

He acquired a knowledge of Hebrew by studying with a Jew who converted to Christianity, and took the unusual position (for that time) that the Hebrew, and not the Septuagint, was the inspired text of the Old Testament. He used this knowledge to translate what became known as the Vulgate, and his translation was slowly but eventually accepted in the Catholic church.[6] Obviously, the later resurgence of Hebrew studies within Christianity owes much to him.

Jerome sometimes seemed arrogant, and occasionally despised or belittled his literary rivals, especially Ambrose. It is not so much by absolute knowledge that he shines, as by a certain poetical elegance, an incisive wit, a singular skill in adapting recognized or proverbial phrases to his purpose, and a successful aiming at rhetorical effect.

He showed more zeal and interest in the ascetic ideal than in abstract speculation. It was this strict asceticism that made Martin Luther judge him so severely. In fact, Protestant readers are not generally inclined to accept his writings as authoritative. The tendency to recognize a superior comes out in his correspondence with Augustine (cf. Jerome's letters numbered 56, 67, 102-105, 110-112, 115-116; and 28, 39, 40, 67-68, 71-75, 81-82 in Augustine's).

Despite the criticisms already mentioned, Jerome has retained a rank among the western Fathers. This would be his due, if for nothing else, on account of the great influence exercised by his Latin version of the Bible upon the subsequent ecclesiastical and theological development.

Prophetic exegesis[edit]

Jerome's Commentary on Daniel, 407 AD, was expressly written to offset the criticisms of Porphyry (231-301)[7] who taught that the book of Daniel related entirely to the time of Antiochus Epiphanes and was written by an unknown individual living in the second century BCE. Jerome's exposition of Daniel was incorporated into the Glossa Ordinaria of Walafrid Strabo, the standard marginal notes of medieval Latin Bibles.[8] Against Porphyry, Jerome identified Rome as the fourth kingdom of chapters 2 and 7, but his view of chapters eight and eleven was more complex. Chapter eight describes the activity of Antiochus Epiphanes who is understood as a "type" of a future antichrist; chapter 11:24 onwards applies primarily to a future antichrist but was partially fulfilled by Antiochus.

The works of Hippolytus and Irenaeus greatly influenced Jerome's interpretation of prophecy.[9] He noted the distinction between the original Septuagint and Theodotion's later substitution[10]

Jerome's writings about the book of Daniel have been analysed by L. E. Froom.[11]. Froom demonstrated that Jerome identifies the four prophetic kingdoms symbolized in Daniel 2 as Babylon, Medes and Persians, Macedon and Rome.[12] Jerome understood the partitioning of the Roman Empire into fragments by the barbarians, as fulfillment of the feet of iron and clay.[13][14] According to Froom, Jerome identifies the stone cut out without hands as "the Lord and Saviour"[15] Jerome identifies the four beasts of Daniel 7 as the same kingdoms of Daniel 2.[16]

Froom also commented on Jerome's understanding of the antichrist. He shows that Jerome refuted Porphyry's application of the Little Horn to Antiochus, and expected that Rome would be divided into ten kingdoms before the Little Horn can appear.[17] Jerome held that the Antichrist would appear in the near future,[18] and taught that he would come from within the church, not the Jewish temple.[19] The antichrist would rule for three and a half years,[20] and his rule would end with the second coming[21]

According to Froom's analysis, Jerome believed that Cyrus of Persia is the higher of the two horns of the Medo-Persian ram of Daniel 8:3. The hairy goat is Grecia smiting Persia.[22] Alexander is the great horn. Which is then succeeded by Alexander's half brother Philip and three of the generals.[23]

Jerome applied chapter 8 first and foremost to Antiochus Epiphanes but also observed that "our [people] think that all these things are prophesied of Antichrist who will be in the last time."[24] With others, Jerome surmises that he will arise from the Jews and come from Babylon, and mentions the belief of "many of ours" that he will be Nero.[25]

Froom showed that, in Jerome's understanding, "Babylon" refers to Rome in the book of Revelation.[26]

Year-day principle[edit]

In his exposition of Ezekiel 4:6 Jerome attempts to outline the 390 years of the captivity of the Israelites, represented by Ezekiel's lying on his left side, beginning with Pekah and ending with the fortieth year of Artaxerxes Mnemon, whom he supposes to be the Ahasuerus of Esther. He makes the forty days during which Ezekiel had to lie on his right side refer to forty years, beginning with the first year of Jechoniah and ending with the first year of Cyrus, king of the Persians.[27] On this point Elliott remarks that Jerome incidentally supports the old Protestant view of furnishing a Scriptural precedent for the year-day theory.[28]

Jerome apparently acquiesces in the application of the year-day principle to the seventy weeks as made by others whom he quotes at great length; but he himself refuses to set forth an interpretation of the seventy weeks, for "it is dangerous to judge concerning the opinions of the masters of the church."[29] He thereupon gives the interpretations of Africanus, Eusebius, Hippolytus, Apollinaris of Laodicea, Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Tertullian, and "the Hebrews," so that the reader may choose for himself.[citation needed]

Quotes[edit]

- I praise wedlock, I praise marriage, but it is because they give me virgins. (Jerome's Letter XXII to Eustochium, section 20 on-line)

- Be ever engaged, so that whenever the devil calls he may find you occupied.

- Ignorance of the Scriptures is ignorance of Christ. (Jerome's Prologue to the “Commentary on Isaiah”: PL 24,17)

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Though "Blessed" in this context does not have the sense of being less than a saint, as in the West.

- ^ Saint Jerome and some library lions

- ^ The lion episode, in Vita Divi Hieronymi (Migne Pat. Lat. XXII, c. 209ff.) was translated by Helen Waddell Beasts and Saints (NY: Henry Holt) 1934) (on-line retelling).

- ^ a b The Collection: St. Jerome, gallery of the religious art collection of New Mexico State University, with explanations. Accessed August 10, 2007.

- ^ Robert Payne, The Fathers of the Western Church, (New York: Viking Press).

- ^ Stefan Rebenich, Jerome (New York: Routlage, 2002), pp. 52-59

- ^ Eremantle, note on Jerome's commentary on Daniel, in NPAF, 2d series, Vol. 6, p. 500.

- ^ Froom, L.E., 1950, "The Prophetic Faith of our Fathers," Vol. 1, Chp. 19, pp. 440-450

- ^ Farrar, Lives, vol. 2, p. 229.

- ^ Jerome, Preface to Daniel, in APNF, 2d series, vol. 6, p. 492.

- ^ Froom, L.E., 1950, "The Prophetic Faith of our Fathers"

- ^ Jerome, Commentaria in Danelem, chap. 2, verses 38-40, in Migne, PL, vol. 25. cols. 503, 504.

- ^ Froom, L.E., 1950, "The Prophetic Faith of our Fathers," Vol. 1, Chp. 19, pp. 440-450; Jerome, Letter 123 (to Ageruchia), in NPNF, 2d series, vol. 6, pp. 236, 237.

- ^ Froom, L.E., 1950, "The Prophetic Faith of our Fathers," Vol. 1, Chp. 19, pp. 440-450; Jerome: Preface to book 1 of his commentary on Ezekiel, in NPNF, 2d series, vol. 6, pp. 499, 500. See Farrar, Lives, vol. 2, pp. 286-288.

- ^ Jerome, Commentaria in Danieluem, chap. 2, verse 40, in Migne, PL, vol. 25 col 504

- ^ Jerome Commentaria in Danielem, chap. 7, verses 7, in Misne, PL, vol. 25. cols. 530

- ^ Jerome, Commentario in Danielem, chap. 7, verses 7, 8, in Migne, PL, vol. 25, cols. 530, 531; Commentaria in Jeremiam, book 5 chap. 25 in Migne, PL, vol. 24, col. 1020.

- ^ Froom, L.E., 1950, "The Prophetic Faith of our Fathers," Vol. 1, Chp. 19, pp. 440-450; Jerome Letter 123 (to Ageruchia) in NPNF 2nd series, vol. 6, p. 236, and note 7; Letter 133 (to Ctesiphon), in NPNF, 2d series, vol. 6, p. 275

- ^ Froom, L.E., 1950, "The Prophetic Faith of our Fathers," Vol. 1, Chp. 19, pp. 440-450; Jerome, Epistle I21 (to Algasia) in Migne, PL, vol. 22, col. 1037.

- ^ Jerome, Commentario in Danielem, chap. 5, verse 25, in Migne, PL, vol. 25, cols. 534.

- ^ Froom, L.E., 1950, "The Prophetic Faith of our Fathers," Vol. 1, Chp. 19, pp. 440-450}; Jerome, Epistle 121 (to algasia) in Migne, PL, vol. 22, col. 1037

- ^ Jerome, Commentaria in Danielem, chap. 8, in Migne, PL, vol. 25, col. 535.

- ^ Jerome, Commentaria in Danielem, chap. 8, in Migne, PL, vol. 25, col. 536

- ^ Jerome, Commentaria in Danielem, chap. 8, on Dan. 11:21 ff., in Migne, PL, vol. 25, col. 565

- ^ Jerome, "Commentaria in Danielem", chap. 8, in Migne, PL, vol. 25, verses 25-30, col. 587, 568.

- ^ Froom, L.E., 1950, "The Prophetic Faith of our Fathers," Vol. 1, Chp. 19, pp. 440-450; Jerome, Commentaria in Isaiam, book 13 chap. 47 in Migne PL vol. 24 col. 454.

- ^ Froom, L.E., 1950, "The Prophetic Faith of our Fathers," Vol. 1, Chp. 19, pp. 440-450; Jerome, Commentaria in Ezechielem, in Migne, PL, vol. 25 cols. 45, 46

- ^ Elliott, op. cit., vol. 4,. p. 322.

- ^ Jerome, Commentaria In Danielem, chap. 9, in Migne, PL, vol. 25, col. 542

External links[edit]

- "St. Jerome" by Louis Saltet, in The Catholic Encyclopedia (1910)

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Jerome

- St. Jerome - Catholic Online

- The Story of St. Jerome and the Lion

- St Jerome (Hieronymus) of Stridonium Orthodox synaxarion

Latin Texts:[edit]

- Chronological list of Jerome's Works with modern editions and translations cited

- Opera Omnia (Complete Works) from Migne edition (Patrologia Latina, 1844-1855) with analytical indexes, almost complete online edition

Google Books' Facsimiles:[edit]

- Migne volume 23 part 1 (1883 edition)

- Migne volume 23 part 2 (1883 edition)

- Migne volume 24 (1845 edition)

- Migne volume 25 part 1 (1884 edition)

- Migne volume 25 part 2 (1884 edition)

- Migne volume 28 (1890 edition?)

- Migne volume 30 (1865 edition)

English Translations:[edit]

- English translations of Biblical Prefaces, Commentary on Daniel, Chronicle, and Letter 120 (tertullian.org)

- English translation of Jerome's De Viris Illustribus

- The Perpetual Virginity of Blessed Mary by St. Jerome

- Lives of Famous Men (CCEL)

- Apology Against Rufinus(CCEL)

- Letters, The Life of Paulus the First Hermit, The Life of S. Hilarion, The Life of Malchus, the Captive Monk, The Dialogue Against the Luciferians, The Perpetual Virginity of Blessed Mary, Against Jovinianus, Against Vigilantius, To Pammachius against John of Jerusalem, Against the Pelagians, Prefaces(CCEL)

Bibliography[edit]

- J.N.D. Kelly, Jerome: His Life, Writings, and Controversies (Peabody, MA 1998)

- S. Rebenich, Jerome (London and New York, 2002)

References[edit]

- Biblia Sacra Vulgata Stuttgart, 1994. ISBN 3-438-05303-9

- This article uses material from Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religion.

- birth/death dates from Cameron, A (1993). The Later Roman Empire. London: Fontana Press. p. 203. ISBN 0-00-686172-5.

Category:Bible translators Category:Roman Catholic theologians Category:Christian apologetics Category:Christian theologians Category:Christian vegetarians Category:Church Fathers Category:Doctors of the Church Category:Chronologists Category:Latin letter writers Category:Late Antique writers Category:347 births Jerome Category:Ancient Roman saints

ar:جيروم be:Еранім Стрыдонскі bg:Йероним ca:Sant Jeroni cs:Svatý Jeroným cy:Sierôm da:Hieronymus de:Hieronymus (Kirchenvater) et:Hieronymus es:Jerónimo de Estridón eo:Sankta Hieronimo fr:Jérôme de Stridon gl:Xerome de Estridón ko:히에로니무스 hr:Sveti Jeronim id:Hieronimus ia:Jeronimo it:San Girolamo he:הירונימוס la:Hieronymus lt:Šv. Jeronimas hu:Szent Jeromos ml:ജെറോം nl:Hiëronymus van Stridon nds-nl:Hiëronymus van Stridon ja:ヒエロニムス no:Hieronymus nn:Hieronymus pl:Hieronim ze Strydonu pt:Jerónimo de Strídon ro:Ieronim ru:Иероним Стридонский sq:Shën Jeronimi sk:Hieronym sr:Јероним Стридонски fi:Hieronymus sv:Hieronymus th:นักบุญเจอโรม uk:Ієронім zh:耶柔米