Wagner Group activities in Africa

The Wagner Group is a Russian paramilitary organization, also described as a private military company (PMC), a network of mercenaries,[1][2] and a de facto unit of the Russian Ministry of Defence (MoD) or Russia's military intelligence agency, the GRU.[3] It has conducted operations in various countries in the African continent since 2017.[4] In November 2023 it was announced that an Africa Corps was being formed as "part of a special structure of the Ministry of Defence"; a US government source said that the Africa Corps was a rival to Wagner that aimed to absorb its personnel and activities in Africa.[5]

Sudan

[edit]In an interview with The Insider in December 2017, veteran Russian officer Igor Strelkov said that Wagner PMCs were present in South Sudan and possibly Libya.[6] Several days before the interview was published, Strelkov stated Wagner PMCs were being prepared to be sent from Syria to Sudan or South Sudan after Sudan's president, Omar al-Bashir, told Russian president Putin that his country needed protection "from aggressive actions of the USA".

Two internal-conflicts have been raging in Sudan for years (in the region of Darfur and the states of South Kordofan and Blue Nile), while a civil war has been taking place in South Sudan since 2013. The head of the private Russian firm RSB-group said that he heard PMCs had already traveled to Sudan and had returned with a severe form of malaria.[7] Several dozen PMCs from RSB-group were sent to Libya in early 2017, to an industrial facility near the city of Benghazi, in an area held by forces loyal to Field marshal Khalifa Haftar, to support demining operations. They left in February after completing their mission.[8] The RSB-group was in Libya at the request of the Libyan Cement Company (LCC).[9]

In mid-December 2017, a video surfaced showing Wagner PMCs training members of the Sudanese military,[10] thus confirming Wagner's presence in Sudan and not South Sudan.[11] The PMCs were sent to Sudan to support it militarily against South Sudan and protect gold, uranium and diamond mines, according to Sergey Sukhankin, an associate expert at the ICPS and Jamestown Foundation fellow. Sukhankin stated that the protection of the mines was the "most essential commodity" and that the PMCs were sent to "hammer out beneficial conditions for the Russian companies".[12]

The PMCs in Sudan reportedly numbered 300 and were working under the cover of "M Invest", a company linked to Yevgeny Prigozhin.[13] "M Invest" signed a contract with the Russian Defense Ministry for the use of transport aircraft of the 223rd Flight Unit of the Russian Air Force and between April 2018 and February 2019, two aircraft of the 223rd made at least nine flights to the Sudanese capital of Khartoum.[14] The Wagner contractors in Sudan included former Ukrainian citizens who were recruited in Crimea, according to the SBU.[15] In 2018, 500 PMCs were reported to have been sent to Sudan's Darfur region to train the military.[16]

In late January 2019, after protests erupted in Sudan mid-December 2018, the British press made allegations that the PMCs were helping the Sudanese authorities crackdown on the protesters. During the first days of the protests, demonstrators and journalists reported groups of foreigners had gathered near major rallying points. This was denied by the Russian Foreign Ministry,[17][18] although it confirmed contractors were in Sudan to train the Sudanese army.[19] The SBU named 149 PMCs it said participated in the suppression of the protests,[20] as well as two that were reportedly killed in the clashes.[21] Between 30 and 40 people were killed during the protests,[22] including two security personnel. More than 800 protesters were detained.[23] Meanwhile, France accused the PMCs of having a "strong, active presence" on social media and that they were pushing a strong "anti-French rhetoric" in the CAR.[24]

Following Omar al-Bashir's overthrow in a coup d'état on 11 April 2019, Russia continued to support the Transitional Military Council (TMC) that was established to govern Sudan, as the TMC agreed to uphold Russia's contracts in Sudan's defense, mining and energy sectors. This included the PMCs' training of Sudanese military officers.[25] The Wagner Group's operations became more elusive following al-Bashir's overthrow. They continued to mostly work with Sudan's Rapid Support Forces (RSF).[16] Wagner was said to be linked to the Deputy Chairman of the TMC and commander of the RSF, Gen. Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo.[26]

In May 2019, Russia signed a military agreement with Sudan[27] which, among other things, would facilitate the entry of Russian warships to Sudanese ports.[28] A new draft agreement was signed in November 2020, that would lead to the establishment of a Russian naval logistic center and repair yard on Sudan's Red Sea coast would host up to 300 people. The agreement is expected to stand for 25 years unless either party objects to its renewal.[29][30]

In April 2020, the Wagner-connected company "Meroe Gold" was reported to be planning to ship personal protective equipment, medicine, and other equipment to Sudan amid the coronavirus pandemic.[31] Three months later, the United States sanctioned the "M Invest" company, as well as its Sudan subsidiary "Meroe Gold" and two individuals key to Wagner operations in Sudan, for the suppression and discrediting of protesters.[32]

Following the October–November 2021 Sudanese coup d'état, Russian support for the military administration set up in Sudan became more open and Russian-Sudanese ties, along with Wagner's activities, continued to expand even after Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, leading to condemnation by the United States, United Kingdom and Norway.[16] The Wagner Group obtained lucrative mining concessions. 16 kilometres (10 mi) from the town of Abidiya, in Sudan's northeastern gold-rich area, a Russian-operated gold mine was set up that was thought to be an outpost of the Wagner Group. Further to the east, Wagner supported Russia's attempts to build a naval base on the Red Sea. It used western Sudan's Darfur region as a staging point for its operations in other neighboring countries, the Central African Republic, Libya and parts of Chad. Geologists of the Wagner-linked "Meroe Gold" company also visited Darfur to assess its uranium potential.[33]

Mid-April 2023, clashes erupted in Sudan between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), broadly loyal to Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and the RSF, following Gen. Dagalo.[34] Subsequently, some Sudanese and regional diplomatic sources claimed that the Wagner Group had provided surface-to-air missiles to the RSF against the SAF.[35] Prigozhin denied supporting the RSF, saying that the company has not had a presence in Sudan for more than two years.[36] Sudan's army chief, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, stated that "So far, there has been no confirmation about the Wagner Group's support for the RSF."[37]

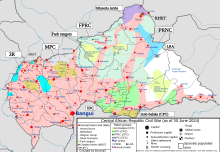

Central African Republic

[edit]

In 2018, the Russian private military company (PMC) Wagner deployed its personnel to the CAR, ostensibly to protect lucrative mines, support the CAR government, and provide close protection for the president, Faustin-Archange Touadéra.[38] The PMCs were also supposed to fill the security vacuum left by France's withdrawal. However, their deployment came despite the active arms embargo in place since 2013.[38]

By May 2018, it was reported that the number of Wagner PMCs in the CAR was 1,400, while another Russian PMC called Patriot was in charge of protecting VIPs.[39] Wagner's presence in the country has been controversial, with some accusing them of human rights abuses and exacerbating the conflict.[40] The Russian government has denied any involvement, saying that the PMCs are working on their own.[41]

In December 2018, the Ukrainian Security Service reported that the umbrella structure of Wagner in the CAR is a commercial firm affiliated with Yevgeny Prigozhin – M-Finance LLC Security Service from St. Petersburg, whose main areas of activity are mining of precious stones and private security services. According to the SBU, some of the PMCs were transported to Africa directly on Prigozhin's private aircraft. Prigozhin was a close ally of Russian president Vladimir Putin and had been sanctioned by the US government for his alleged involvement in election interference and other malign activities before his death in August 2023.[42]

By 2021, the situation in the CAR had deteriorated further, with rebels attacking and capturing the fourth-largest city in the country.[43] In response, Russia sent an additional 300 military instructors to the country to train government forces and provide support.[43] The presence of Wagner and other Russian PMCs in the CAR has raised concerns about Russia's growing influence in Africa and its willingness to flout international law.

In September 2022, The Daily Beast interviewed survivors and witnesses of yet another massacre committed by the Wagner Group in Bèzèrè village in December 2021, which involved torture, killing and disembowelment of a number of women, including pregnant ones.[44]

In mid-January 2023, the Wagner Group sustained relatively heavy casualties as a new government military offensive was launched near the CAR border with Cameroon and Chad. Fighting also erupted near the border with Sudan. The rebels claimed between seven and 17 Wagner PMCs were among the dozens of casualties. A CAR military source also confirmed seven Wagner contractors were killed in one ambush.[45]

According to a 2022 joint investigation and report from European Investigative Collaborations (EIC), the French organization All Eyes on Wagner, and the UK-based Dossier Center, Wagner Group has been controlling Diamville diamond trading company in Central African Republic since 2019.[46]

Deaths of journalists

[edit]On 30 July 2018, three Russian journalists (Kirill Radchenko, Alexander Rastorguyev and Orkhan Dzhemal) belonging to the Russian online news organisation Investigation Control Centre (TsUR), which is linked to Mikhail Khodorkovsky, were ambushed and killed by unknown assailants in the Central African Republic, three days after they had arrived in the country to investigate local Wagner activities. The ambush took place 23 kilometers from Sibut when armed men emerged from the bush and opened fire on their vehicle. The journalists' driver survived the attack,[47] but was afterward kept incommunicado by the authorities. In its response to the killings, Russia's foreign ministry noted that the dead journalists had been traveling without official accreditation.[48]

BBC News and AFP said the circumstances of their deaths were unclear.[49][50] According to the Interfax news agency, robbery could have been a motive. An expensive camera kit and more than 8,000 dollars disappeared from the scene,[49] although three canisters of gasoline, which is considered a valuable commodity in the CAR, were left in the vehicle.[51] A local official and their driver stated that the attackers were wearing turbans and speaking Arabic.[49][52] Russian and CAR state media initially reported that the authorities suspected Seleka rebels to be behind the killings.[53] According to local residents, interviewed by Khodorkovsky's investigators, around 10 people had camped out nearby before the ambush, waiting there for several hours. Shortly before the attack, they saw another car with "three armed white men ... and two Central Africans" pass by.[51]

Per an initial report in The New York Times, there was no indication that the killings were connected with the journalists' investigation of the Wagner Group's activities in the Central African Republic,[54] but a follow-up article cited a Human Rights Watch researcher who commented that "Many things don't add up" in regards to the mysterious killings. It reaffirmed there was nothing to contradict the official version that the killings were a random act by thieves, but noted speculation within Russia that blamed the Wagner Group, while also adding a theory by a little known African news media outlet that France, which previously ruled the CAR when it was a colony, was behind the killings as a warning to Moscow to stay clear of its area of influence.[48] Moscow-based defence analyst Pavel Felgenhauer thought it was unlikely they were killed by Wagner's PMCs,[55] while the Security Service of Ukraine claimed that it had evidence about the PMCs involvement.[56]

During their investigation, the journalists tried to enter the PMCs' camp, but they were told that they needed accreditation from the country's Defense Ministry.[54] The accreditation was previously only given to an AFP journalist who was still not allowed to take any photographs or interview anyone. The killings took place one day after the journalists visited the Wagner Group encampment at Berengo.[52] According to Bellingcat's Christo Grozev, after the journalists arrived in the CAR, the Wagner Group's Col. Konstantin Pikalov issued a letter describing how they should be followed and spied on.[citation needed]

According to the Dozhd television station, the Russian private military company Patriot was involved in the killings.[57]

In January 2019, it was revealed that, according to evidence gathered by Khodorkovsky's Dossier Center, a major in the Central African Gendarmerie was involved in the ambush. The major was in regular communication with the journalists' driver on the day of their murders and he had frequent communications with a Wagner PMC who was a specialist trainer in counter-surveillance and recruitment in Central Africa. The police officer was also said to have attended a camp run by Russian military trainers on the border with Sudan, and maintained regular contact with Russian PMCs after his training.[58] The investigation into the murders by the Dossier Center was suspended two months later due to lack of participation by government agencies and organizations.[59]

Madagascar

[edit]The independent media group the Project reported that Wagner PMCs arrived in Madagascar in April 2018, to guard political consultants that were hired by Yevgeny Prigozhin to accompany the presidential campaign of then-president Hery Rajaonarimampianina for the upcoming election. Rajaonarimampianina lost the attempt at re-election, finishing third during the first round of voting,[60] although Prigozhin's consultants were said to had also worked with several of the other candidates in the months before the elections. Close to the end of the campaign, the strategists also helped the eventual winner of the elections, Andry Rajoelina, who was also supported by the United States and China.[61] One of the last acts of Rajaonarimampianina's administration was said to be to facilitate a Russian firm's takeover of Madagascar's national chromite producer "Kraoma"[62] in August 2018. On August 9th, 2018 the director Arsène Rakotoarisoa dismissed after having paid a ransom of 100 millions Ariary for the kidnapping of 4 employees of the company.[63] Wagner PMCs were reported to be guarding the chrome mines as of October 2018.[60]

Though, as president Hery Rajaonarimampianina lost the 2018 Malagasy presidential elections in the end of that year, the Russian company Ferrum Mining, a company with a capital of Rubles 10.000 (€100), did not inject funds into the company.[64] and left the employees unpaid.[65] In 2019 only 15000 tons of chromium were exported by the company[66] and since then the operations had been stopped and the salaries remained unpaid in the end of 2022.[67]

Among the consultants to the different presidential candidates was also Konstantin Pikalov, who was initially assigned as campaign security chief to candidate Pastor Mailhol of Madagascar's Church of the Apocalypse. However, when it was clear Andry Rajoelina was the favorite to win the election, Pikalov was transferred to be Rajoelina's bodyguard.[68]

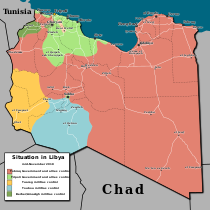

Libya

[edit]

The group's presence in Libya was first reported in October 2018, when The Sun claimed that Russian military bases had been set up in Benghazi and Tobruk in support of Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar, who leads the Libyan National Army (LNA).[69] The group was said to be providing training and support to Haftar's forces, and Russian missiles and SAM systems were also thought to be set up in Libya.[70]

The Russian government denied the report, but RBK TV confirmed the Russian military deployment to Libya. By early March 2019, around 300 Wagner PMCs were in Benghazi supporting Haftar, according to a British government source.[71] The LNA made large advances in the country's south, capturing a number of towns in quick succession, including the city of Sabha and Libya's largest oil field.[72] Following the southern campaign, the LNA launched an offensive against the Government of National Accord (GNA)-held capital of Tripoli, but the offensive stalled within two weeks on the outskirts of the city due to stiff resistance.[73]

Reports suggested that Russian mercenaries from the Wagner Group were fighting on the side of Haftar's forces, providing artillery support, using snipers, and laying mines and improvised explosive devices.[74] and Mozambique,[75] They were also said to be equipped with laser-guided howitzer shells and using hollow point ammunition in contravention of rules of war.[76] A Wagner headquarters was set up at a hospital in the town of Esbia, where the PMCs were stated to have detained and shot the family of a man who had stumbled upon the contractors by mistake.[77] The GNA stated that two Russians who were arrested by their forces in early July were employed by the Wagner Group, and were involved in "securing a meeting" with Saif al-Islam Gaddafi.[78]

By mid-November, the number of Wagner PMCs in Libya had risen to 1,400, according to several Western officials.[79] The US Congress was preparing bipartisan sanctions against the PMCs in Libya, and a US military drone was shot down over Tripoli, with the US claiming it was shot down by Russian air defenses operated by Russian PMCs or the LNA. An estimated 25 Wagner military personnel were killed in a drone strike in September 2020, although the Russian government denied any involvement. The GNA ultimately recaptured Tripoli in June 2020, leading to a ceasefire agreement in October 2020.[80]

On 31 May 2022, Human Rights Watch stated that information from Libyan agencies and demining groups linked the Wagner Group to the use of banned landmines and booby traps in Libya. These mines killed at least three Libyan deminers before the mines' locations were identified.[81]

Mozambique

[edit]In early August 2019, the Wagner Group received a contract with the government of Mozambique over two other private military companies, OAM and Black Hawk, by offering their services for lower costs.[82] At the end of that month,[83] the government of Mozambique approved a resolution ratifying the agreement from April 2018 on the entry of Russian military ships into national ports.[84] On 13 September 160 PMCs from the Wagner Group arrived on a Russian An-124 cargo plane in the country[85] to provide technical and tactical assistance to the Mozambique Defence Armed Forces (FADM) and were stationed in three military barracks in the northern provinces of Nampula, Macomia and Mueda.[84]

On 25 September, a second Russian cargo plane[85] landed in Nampula province and unloaded large-calibre weapons and ammunition belonging to the Wagner Group, which were then transported to the Cabo Delgado Province where, since 5 October 2017, an Islamist insurgency had been taking place.[84] At least one of the two cargo planes belonged to the 224th Flight Unit of the Russian Air Force.[85] Overall, 200 PMCs, including elite troops, three attack helicopters and crew arrived in Mozambique to provide the training and combat support in Cabo Delgado, where the Islamist militants had burned villages, carried out beheadings and displaced hundreds of people.[86]

Starting on 5 October, the Mozambique military conducted several successful operations, in collaboration with the PMCs, against the insurgents[75] along the border with Tanzania.[85] At the start of the operations, a PMC unit commander with the call sign "Granit" was killed and two other PMCs were wounded when their unit was ambushed by a force of 60 insurgents.[87] During these operations, the military and the PMCs bombed insurgent bases in two areas, pushing them into the woods. At this time, the insurgents launched attacks on two bases, during which more than 35 insurgents and three PMCs were killed. Meanwhile, on 8 October, a Russian ship entered the port of Nacala carrying just over 17 containers of different types of weapons, especially explosives, which were transported to the battlefield.[75] Russia, on its part, denied it had any troops in Mozambique.[88]

Following the arrival of the PMCs, ISIL reinforced jihadist forces in Mozambique, leading to an increase in the number of militant attacks.[89] On 10 and 27 October, two ambushes took place during which seven PMCs were killed. During the ambush at the end of October, in addition to five PMCs, 20 Mozambique soldiers also died when Islamic militants set up a barricade on the road as a FADM military convoy arrived. Four of the five PMCs were shot dead and then beheaded.[90] Three vehicles were burned in the attack.[91] Some of the deaths during the fighting in Mozambique were reportedly the result of a "friendly fire" incident.[92]

By mid-November, two Mozambique military sources described growing tensions between Wagner and the FADM after a number of failed military operations, with one saying joint patrols had almost stopped. Analysts, mercenaries and security experts, including the heads of OAM and Black Hawk, which operate in Sub-Saharan Africa, were of the opinion that Wagner was struggling in Mozambique since they were operating in a theater where they did not have much expertise. According to John Gartner, the head of OAM and a former Rhodesian soldier, the Wagner Group was "out of their depth" in Mozambique. At the same time, Dolf Dorfling, the founder of Black Hawk and a former South African colonel, said sources told them that the Wagner Group had started to search for local military expertise.[82]

Towards the end of that month, it was reported that 200 PMCs had withdrawn from Mozambique, following the deaths among its fighters.[92] Still, as of the end of November, Russian fighters and equipment were still present in the port city of Pemba and they were also based in the coastal town of Mocímboa da Praia.[85] The PMCs had also withdrawn to Nacala to re-organize.[89]

By early 2020, the number of attacks in Cabo Delgado surged, with 28 taking place throughout January and early February. The violence spread to nine of the province's 16 districts. The attacks included beheadings, mass kidnappings and villages burned to the ground. Most of the attacks were conducted by militants, but some were also made by bandits.[93] On 23 March, the militants captured the key town of Mocimboa de Praia in Cabo Delgado.[94] Two weeks later, the insurgents launched attacks against half a dozen villages in the province.[95]

On 8 April, the military launched helicopter strikes against militant bases in two districts. Journalist Joseph Hanlon published a photograph showing one of the helicopter gunships that took part in the attack and said it was manned by Wagner PMCs. However, two other sources cited by the Daily Maverick stated the contractors belonged to the South African private military company Dyck Advisory Group (DAG) and that the Wagner Group had pulled out of Mozambique in March.[96]

Mali

[edit]

In mid-September 2021, according to diplomatic and security sources, an agreement was close to being finalized that would allow the Wagner Group to operate in Mali. According to conflicting sources, at least 1,000 PMCs or less would be deployed to Mali, which has been witnessing a civil war since 2012, and the Wagner Group would be paid about 6 billion CFA francs a month for training of the Malian military and providing protection for government officials. France, which previously ruled Mali as a colony, was making a diplomatic push to prevent the agreement being enacted. Since late May 2021, Mali has been ruled by a military junta that came into power following a coup d'état.[98] In response, Malian prime minister Choguel Kokalla Maïga, in his address to the UN General Assembly, stated "The new situation resulting from the end of Operation Barkhane puts Mali before a fait accompli – abandoning us, mid-flight to a certain extent – and it leads us to explore pathways and means to better ensure our security autonomously, or with other partners".[99]

The United Kingdom, European Union and Ivory Coast also warned Mali not to engage in an agreement with the Wagner Group.[100][101][102] Still, on 30 September, Mali received a shipment of four Mil Mi-17 helicopters, as well as arms and ammunition, as part of a contract agreed in December 2020. The shipment was received by Mali's defence minister, who praised Russia as "a friendly country with which Mali has always maintained a very fruitful partnership".[103][104]

In late December, France published a joint statement also signed by the U.K., Germany, Canada and 11 other European governments that they have witnessed the deployment of the Wagner Group to Mali, with Russia's backing, and that they condemned the action.[105][106] Mali denied the deployment, asking for proof by independent sources, but acknowledged "Russian trainers" were in the country as part of strengthening the military and security forces and that it was "only involved in a state-to-state partnership with the Russian Federation, its historical partner".[107] French government sources stated the allegation of Wagner's deployment was based on factors that included the development of a new military base near Bamako's airport as well as "suspicious flight patterns".[108]

The following month, Malian army officials confirmed some 400 Russian military advisors had arrived in the country and were present in several parts of Mali.[109] Several officials, including a Western one, stated Russian "mercenaries" were deployed in Mali, but a Malian military source denied this. Still, an official from central Mali, stated there was both Russian advisors and PMCs present and that not all of the contractors were Russian nationals.[109] According to a French military official, between 300 and 400 PMCs were present in the central part of the country, along with Russian trainers who were providing equipment.[110] Photos emerged of the PMCs in the town of Ségou from the end of December 2021, where 200 Wagner contractors were reportedly deployed. It was reported that at the beginning of January 2022, clashes south of Mopti between the contractors and jihadists left one PMC dead.[111]

In mid-January 2022, Wagner PMCs were deployed at a former French military base in Timbuktu, in northern Mali.[112][113] Subsequently, the US Army also confirmed the presence of the Wagner Group in Mali.[114] By early April 2022, some 200 Malian soldiers and 9 police officers were receiving training in Russia.[115]

On 5 April 2022, Human Rights Watch published a report accusing Malian soldiers and Russian PMCs of executing around 300 civilians between 27 and 31 March, during a military operation in Moura, in the Mopti region, known as a hotspot of Islamic militants. According to the Malian military, more than 200 militants were killed in the operation, which reportedly involved more than 100 Russians.[116][117] At the start of the operation on 27 March, Malian military helicopters landed near the town's market, after which soldiers were deployed and approached a group of around 30 jihadists, who fired at them, killing at least two "white soldiers", according to Human Rights Watch.[118]

On 19 April 2022, the first officially confirmed death of a Russian military advisor, said to be a Wagner member, took place when a military patrol hit a roadside bomb near the town of Hombori.[119] On 22 April 2022, three days after the French military handed over the Gossi military base to Malian forces, France claimed suspected Wagner Group PMCs buried a dozen bodies in a mass grave a few kilometres east of the base soon after the withdrawal, with the intent of blaming France. The French military published video images appearing to show 10 white soldiers covering bodies with sand, two days after a "sensor observed a dozen Caucasian individuals, most likely belonging to the Wagner Group" and Malian soldiers arriving at the burial site to unload equipment, according to a French military report.[120] On 25 April 2022, the Al-Qaeda-linked JNIM jihadist organisation claimed it had captured a number of Wagner Group members at the beginning of the month in the central Ségou Region.[121]

In late June 2022, accusations surfaced against the Wagner Group that PMCs were looting towns and indiscriminatly arresting people in the northern Tombouctou Region with the Malian military, forcing civilians to flee to Mauritania. Killings were also reported to have taken place.[122] On 24 July, the US sanctioned three Malian officials for facilitating the Wagner Group's operations in their country.[123]

On 16 June 2023, the Malian government requested that MINUSMA peacekeepers withdraw from Mali without delay.[124] On 30 June, the UN Security Council approved the request for the removal of peacekeepers.[125] Subsequently, in response to the alleged refusal by the Malian government to implement the Algiers agreement with the Tuareg rebels, the main groups that make up the Coordination of Azawad Movements (CMA) – the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad, the Arab Movement of Azawad, and the High Council for the Unity of Azawad – withdrew from peace talks.[126] They later merged into one group.[127]

On 9 September 2023, CMA rebels shot down the Malian airforce's only SU-25,[128] while the JNIM shot down a Mi-8 helicopter operated by the Wagner Group.[129] On 11 September 2023, the CMA declared itself to be at "war" with the junta.[130]

Following a number of deadly rebel attacks in September and October 2023, on military bases,[131][132][133][134] government forces launched an offensive in the direction of the rebel stronghold of Kidal, controlled by the CMA.[135] Its primary destinations were to be, specifically, the localities of Tessalit and Aguelhok, towns that still maintain MINUSMA military bases within them.[136] Clashes between the Malian army and the rebels erupted around Anefif on 6 October, with the Malian army eventually taking control of the town.[137][138] On 16 October, MINUSMA started their departure from the two bases,[139] leaving Tessalit on 21 October,[140] and Aguelhok on 23 October.[141] As they were withdrawing from the base at Tessalit, Malian and Wagner troops were flown in to replace them.[140]

On 12 November 2023, the Malian military and the Wagner Group restarted their advance from Anefif, where they had been stationed since early October, towards Kidal.[142] Two days later, the military, supported by Wagner, captured Kidal,[143] with the PMCs subsequently allowing local residents in the city to take pictures and videos with them in their first public display in Mali. The residents in the videos greeted them as liberators.[144] Before they entered the town, government and Wagner forces struck rebel targets in and around Kidal in drone strikes.[145] On 22 November, the PMCs flew their flag over Kidal's fort.[146]

On 22 July 2024, a convoy of Wagner mercenaries and Malian soldiers engaged with rebels in Inafarak, northern Mali, and successfully captured the community the next day.[147] The convoy later moved to the commune of Tinzaouaten, where it was ambushed by the Tuareg rebel group Strategic Framework for the Defense of the People of Azawad on 25 July, and a three-day battle ensued.[148] Over the course of the fighting, the Wagner Group lost between 20 and 80 men according to Russian Telegram sources, making it their biggest loss in Mali since it was deployed there.[149][150]

Burkina Faso

[edit]Following more than six years of a Jihadist insurgency in Burkina Faso, a coup d'état took place on 23 January 2022, with the military deposing president Roch Marc Christian Kaboré[151] and declaring that the parliament, government and constitution had been dissolved.[152] The coup d'état was led by lieutenant colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba[153] and came in response to the government's failure to suppress the Islamist insurgency, which has left 2,000 people dead and between 1.4 and 1.5 million displaced. Anger was also directed towards France, which was providing military support to the government.[154][155][156][157]

One day after the coup, Alexander Ivanov, the official representative of Russian military trainers in the CAR, offered training to the Burkinese military.[158] Subsequently, it was revealed that shortly before the military takeover lieutenant colonel Damiba attempted to persuade president Kaboré to engage the Wagner Group against the Islamist insurgents.[159] In addition, less than two weeks before the takeover, the government announced it had thwarted a coup plot, after which it was speculated that the Wagner Group might try and establish itself in Burkina Faso.[113] The coup found significant support in the country[155] and was followed by protests against France and in support of the takeover, with the protesters calling for Russia to intervene.[154] The United States Department of Defense stated it was aware of allegations that the Wagner Group might have been "a force behind the military takeover in Burkina Faso" but could not confirm if they were true.[158]

On 30 September 2022, a new coup d'état took place that saw colonel Damiba being deposed by captain Ibrahim Traoré due to Damiba's inability to contain the jihadist insurgency. According to Traoré, he and other officers had tried to get Damiba to "refocus" on the rebellion, but eventually opted to overthrow him as "his ambitions were diverting away from what we set out to do".[160] Some suspected Traoré of having a connection with Wagner.[161] As Traoré entered Ouagadougou, the nation's capital, supporters cheered, some waving Russian flags.[162] Senior U.S. diplomat Victoria Nuland traveled to Burkina Faso in the wake of Traoré's seizure of power in order to "strongly urge" him not to partner with Wagner.[163]

Still, the Government of Ghana publicly alleged that Traoré began collaborating with the Wagner Group following the coup, enlisting the mercenaries against the jihadist rebels.[164] According to Ghana's president, the ruling junta allocated a mine to the Wagner Group as a form of payment for its deployment,[165] which was denied by Burkina Faso's mines minister.[166] In late January 2023, the ruling junta demanded France withdraw its troops, numbering between 200 and 400 special forces members, from Burkina Faso, after battling the jihadists for years. France agreed[167][168] and completed its withdrawal by 19 February 2023.[169]

On 24 January 2024, military personnel of Russia's Africa Corps, which is intended to replace Wagner, arrived in Burkina Faso to provide security, including for Traoré. It was reportedly planned that the 100 personnel would be expanded to 300.[170] It was revealed that a military base for the Africa Corps was established in Loumbila.[171]

Suspected

[edit]Chad

[edit]The U.S. government shared intelligence with the Chadian government that Wagner is working with rebels in the country to destabilise the government, and is possibly plotting to assassinate the country's president[172] as well as other top government officials. Wagner was allegedly also seeking to forge ties with elements of the Chadian ruling class. An attempt to topple a government represented a watershed for Wagner's influence building strategy, a U.S. official told The New York Times. The U.S. approach of intelligence sharing to counter Russian threats to sovereign states and subsequent leaks of the intelligence findings reflects a strategy pioneered amid the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[163]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Faulkner, Christopher (June 2022). Cruickshank, Paul; Hummel, Kristina (eds.). "Undermining Democracy and Exploiting Clients: The Wagner Group's Nefarious Activities in Africa" (PDF). CTC Sentinel. 15 (6). West Point, New York: Combating Terrorism Center: 28–37. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 July 2022. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ^ "What is the Wagner Group, Russia's mercenary organisation?". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

"From a legal perspective, Wagner doesn't exist," says Sorcha MacLeod

- ^ Higgins, Andrew; Nechepurenko, Ivan (7 August 2018). "In Africa, Mystery Murders Put Spotlight on Kremlin's Reach". The New York Times. New York. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- ^ Rampe, William. "What Is Russia's Wagner Group Doing in Africa?". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 2023-07-28.

- ^ Bobin, Frédéric; Le Cam, Morgane (December 15, 2023). "Africa Corps, le nouveau label de la présence russe au Sahel" [Africa Corps, the new label of the Russian presence in the Sahel]. Le Monde (in French). Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ^ "Игорь Гиркин (Стрелков): "К власти и в Донецкой, и в Луганской республике Сурков привел бандитов"". Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ "После Сирии российские ЧВК готовы высадиться в Судане". BBC News Русская Служба. 4 December 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ Tsvetkova, Maria (13 March 2017). "Exclusive: Russian private security firm says it had armed men in east". Reuters. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ "The Libyan army has explained the invitation of the Russian PMCs – FreeNews English – FreeNews-en.tk". freenews-en.tk. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ "Появилось видео из Судана, где российские наемники тренируют местных военных". Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ "Журналист показал "будни российской ЧВК в Судане"". 12 December 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ Ioanes, Ellen (19 November 2019). "These are the countries where Russia's shadowy Wagner Group mercenaries operate". Business Insider.

- ^ SBU Head Vasyl Hrytsak: Russian military intelligence units break up democratic protests in Sudan Archived 1 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine

ARE RUSSIAN MERCENARIES OPERATING IN SUDAN? - ^ Tim Lister; Sebastian Shukla; Nima Elbagir (25 April 2019). "A Russian company's secret plan to quell protests in Sudan". CNN.

- ^ "В оккупированном Крыму прошел набор людей в ряды ЧВК "Вагнера" – руководитель аппарата СБУ". Интерфакс-Украина.

- ^ a b c "Russia, Wagner Group expand ties with Sudan – Al-Monitor: The Pulse of the Middle East". www.al-monitor.com. 13 April 2022.

- ^ "Russian private contractors active in Sudan during protest crackdown". Middle East Eye. 24 January 2019. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ Flanagan, Jane. "Russian mercenaries help put down Sudan protests". The Times.

- ^ "Russian contractors are training the army in Sudan, says Moscow". Reuters.com. 23 January 2019.

- ^ "Wagner PMC is secret detachment of Russia's General Staff of Armed Forces – confirmed by mercenaries' ID papers, says SBU Head Vasyl Hrytsak. Now we'll only have to wait for information from Russian officials as to which particular "Cathedral" in Sudan or :: Security Service of Ukraine". 29 January 2019. Archived from the original on 29 January 2019.

- ^ "Hrytsak: "The lie stained with blood, greed and fear for the committed crimes – this is the true face of Russian special services. The situation with the passports of killed mercenaries is a glaring confirmation." :: Security Service of Ukraine". ssu.gov.ua. Archived from the original on 26 June 2020. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia announce solidarity for Sudan Al Bashir". Gulf News. 30 January 2019.

- ^ "More than 800 detained in ongoing Sudan protests: Minister". Al Jazeera. 7 January 2019. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ "France WARNING: Russian mercenaries PLOTTING in Africa – 'We know you!'". 25 January 2019. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- ^ "Moscow's Hand in Sudan's Future". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- ^ "Putin's Exploitation of Africa Could Help Him Evade Sanctions". news.yahoo.com. 8 April 2022.

- ^ "Russia reveals deal allowing it to use Sudan ports". Middle East Monitor. 25 May 2019.

- ^ "UAWire – Russia signs military deal with Sudan". uawire.org.

- ^ Bratersky, Alexander (13 November 2020). "Sudan to host Russian military base". Defense News.

- ^ "Russia plans naval base in Sudan". Al Jazeera.

- ^ AGENCIES, DAILY SABAH WITH (16 July 2020). "US imposes sanctions on Russia's Wagner Group over role in Libya, Sudan". Daily Sabah.

- ^ Walsh, Declan (5 June 2022). "From Russia With Love': A Putin Ally Mines Gold and Plays Favorites in Sudan". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ Fulton, Adam; Holmes, Oliver (27 April 2023). "Sudan conflict: why is there fighting and what is at stake in the region?". The Guardian.

- ^ Elbagir, Nima; Mezzofiore, Gianluca; Qiblawi, Tamara (20 April 2023). "Exclusive: Evidence emerges of Russia's Wagner arming militia leader battling Sudan's army". CNN. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

The Russian mercenary group Wagner has been supplying Sudan's Rapid Support Forces (RSF) with missiles to aid their fight against the country's army, Sudanese and regional diplomatic sources have told CNN. The sources said the surface-to-air missiles have significantly buttressed RSF paramilitary fighters and their leader Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo

- ^ "Russia's Wagner denies involvement in Sudan crisis". BBC. 19 April 2023. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023.

- ^ "Sudan's army chief says Haftar denies supporting RSF; no confirmation on Wagner Group's involvement". Al-Ahram. 22 April 2023. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023.

- ^ a b Kharief, Akram (24 May 2018). "Foreign mercenaries in new scramble for Africa and the Sahel". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ "Как Россия подвергает своему влиянию кризисные страны Африки". inopressa.ru.

- ^ "UN urges CAR to cut ties with Russia's Wagner mercenaries over rights abuses". France 24. 28 October 2021.

- ^ "Chad accuses Central African Republic of 'war crime' after attack on outpost". France 24. 31 May 2021.

- ^ "'Covert activity of Russian mercenaries of Wagner's PMC in CAR should be subject of international investigation', says SBU Head Vasyl Hrytsak". Security Service of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 22 December 2018. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- ^ a b Rebels seize Central African Republic's fourth-largest city five days before nationwide elections, France 24, 22 December 2020

- ^ Obaji, Philip Jr. (2022-09-03). "Putin's Private Army Accused of Committing Their Most Heinous Massacre Yet". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 2022-09-07.

- ^ Salih, Zeinab Mohammed; Burke, Jason (2 February 2023). "Wagner mercenaries sustain losses in fight for Central African Republic gold". The Guardian.

- ^ "Una investigación internacional revela que el Grupo Wagner saquea y exporta diamantes centroafricanos a Europa." La Nación, 2 Dec. 2022, p. NA. Gale General OneFile, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A728858039/ITOF?u=wikipedia&sid=ebsco&xid=fc37a001. Accessed 14 Dec. 2022.

- ^ "Three Russian journalists killed in Central African Republic ambush". Reuters. 31 July 2018.

- ^ a b Higgins, Andrew; Nechepurenko, Ivan (7 August 2018). "In Africa, Mystery Murders Put Spotlight on Kremlin's Reach". The New York Times. New York. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- ^ a b c "Murder of three journalists shocks Russia". BBC News. 2 August 2018.

- ^ "Russian journalists killed investigating private army in Central African Republic". France 24. 1 August 2018.

- ^ a b Kara-Murza, Vladimir. "The Kremlin's mysterious mercenaries and the killing of Russian journalists in Africa". The Washington Post. Opinion.

- ^ a b Philip Obaji Jr and Anna Nemtsova (4 August 2018). "Murdered Russian Journalists in Africa Were Onto Something Dangerous for Putin". The Daily Beast.

- ^ Luhn, Alec (1 August 2018). "Russian journalists killed in Central African Republic while investigating mercenaries of 'Putin's chef'". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022.

- ^ a b Nechepurenko, Ivan (31 July 2018). "3 Russian Journalists Killed in Central African Republic". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018.

- ^ "Reporters' deaths put spotlight on Russian private army, the Wagner Group". South China Morning Post. 2 August 2018.

- ^ "SBU Possesses Evidence Of Involvement Of Russian Mercenaries Of Wagner PMC In Murder Of 3 Russian Journalists In CAR". ukranews.com. 8 October 2018.

- ^ "Источники Дождя: к убийству журналистов в ЦАР может быть причастна ЧВК "Патриот"". tvrain.tv. 28 September 2018. Retrieved February 19, 2023.

- ^ Tim Lister; Sebastian Shukla (10 January 2019). "Murdered journalists were tracked by police with shadowy Russian links, evidence shows". CNN.

- ^ "Центр 'Досье' приостановил расследование гибели журналистов в ЦАР". Рамблер/новости. 30 March 2019.

- ^ a b "Новая газета – Novayagazeta.ru". Новая газета – Novayagazeta.ru. Archived from the original on 9 March 2022. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ "Master and Chef: Prigozhin and Madagascar". Проект. 14 March 2019.

- ^ "Russians muscle in on chrome industry". Africa Intelligence. 23 November 2018.

- ^ [1]

- ^ www.malina.mg

- ^ MADAGASCARL’exploitation de chromite passe aux mains du Russe Ferrum Mining1 AVR 2019

- ^ Privée de son partenaire russe, Kraoma cherche sa rentabilité

- ^ Mines: Kraoma dans l'impasse

- ^ "Putin Chef's Kisses of Death: Russia's Shadow Army's State-Run Structure Exposed". bellingcat. 14 August 2020.

Wagner Group – which does not exist on paper – got its name from its purported founder and commander

- ^ "Putin Plants Troops, Weapons in Libya to Boost Strategic Hold". Al Bawaba.

- ^ The Sun: Russia sends troops and missiles to east Libya and sets up two military bases Archived 17 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine The Libya Observer

- ^ Luhn, Alec; Nicholls, Dominic (3 March 2019). "Russian mercenaries back Libyan rebel leader as Moscow seeks influence in Africa". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022.

- ^ "Libya's Khalifa Haftar says NLA has taken largest oil field". The National. 7 February 2019.

- ^ Irish, Ulf Laessing (15 April 2019). "Libya offensive stalls, but Haftar digs in given foreign sympathies". Reuters.

- ^ "Putin-Linked Mercenaries Are Fighting on Libya's Front Lines".

- ^ a b c ""War 'declared'": Report on latest military operations in Mocimboa da Praia and Macomia – Carta". Mozambique.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, David D. (5 November 2019). "Russian Snipers, Missiles and Warplanes Try to Tilt Libyan War". The New York Times.

- ^ "Russian mercenaries in Libya: 'They sprayed us with bullets'". Middle East Eye.

- ^ "Russians arrested as spies in Libya worked for Russian firm Wagner, official says". The Washington Post.

- ^ "U.S. Warns Against Russia's Growing Role in Libya War". Bloomberg. 15 November 2019 – via www.bloomberg.com.

- ^ "Libyan army forces launch full-scale attack on Haftar's militias". The Libya Observer. Archived from the original on 27 January 2022. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "Libya: Russia's Wagner Group Set Landmines Near Tripoli". Human Rights Watch. 31 May 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ a b Sauer, Pjotr (19 November 2019). "In Push for Africa, Russia's Wagner Mercenaries Are 'Out of Their Depth' in Mozambique". The Moscow Times.

- ^ "Mozambique: Cabinet ratifies agreement on simplified entry for Russian military ships". Mozambique.

- ^ a b c "Cabo Delgado insurgency: Russian military equipment arrives in Mozambique – Carta". Mozambique.

- ^ a b c d e Tim Lister; Sebastian Shukla (29 November 2019). "Russian mercenaries fight shadowy battle in gas-rich Mozambique". CNN.

- ^ Flanagan, Jane. "Mozambique calls on Russian firepower". The Times.

- ^ Sturdee, Nick (27 September 2021). "The Wagner Group Files". New Lines Magazine.

- ^ Russia Denies It Has Any Troops Stationed in Mozambique, Bloomberg, 8 October 2019.

- ^ a b Karrim, Azarrah (19 December 2019). "Growing terrorism in Mozambique, with suspected links to ISIS, wreaking havoc with no end in sight". News24.

- ^ Sauer, Pjotr (31 October 2019). "7 Kremlin-Linked Mercenaries Killed in Mozambique in October — Military Sources". The Moscow Times.

- ^ "5 Russian Mercenaries Reportedly Killed in Mozambique Ambush". The Moscow Times. 29 October 2019.

- ^ a b Flanagan, Jane. "Bloodshed and retreat from Mozambique for Putin's private army the Wagner Group". The Times.

- ^ "Beheadings, kidnappings amid surge in Mozambique attacks: UN". Al Jazeera.

- ^ "Jihadists seize Mozambique town in gas-rich region". BBC News. 23 March 2020.

- ^ "Islamists attack multiple villages in northern Mozambique". Upstream Online. 8 April 2020.

- ^ Fabricius, Peter (9 April 2020). "MOZAMBIQUE: 'SA private military contractors' and Mozambican airforce conduct major air attacks on Islamist extremists". Daily Maverick.

- ^ "Mali, CAR watch with concern as Wagner mutiny unfolds in Russia". Africanews. 24 June 2023.

- ^ "Exclusive-Deal allowing Russian mercenaries into Mali is close – sources". Yahoo! News.

- ^ "Mali approached Russian military company for help: Lavrov". Al Jazeera.

- ^ "UK joins calls on Mali to end alleged deal with Russian mercenaries". The Guardian. 30 September 2021.

- ^ "Pentagon Warns Against Deal Bringing Russian Mercenaries to Mali". VOA. 5 October 2021.

- ^ Munshi, Neil (6 October 2021). "Mali summons French ambassador in row over Russian security group". Financial Times.

- ^ AFP, French Press Agency- (1 October 2021). "Mali hails Russia after delivery of 4 military helicopters". Daily Sabah.

- ^ "Mali receives Russian helicopters and weapons, lauds Moscow 'partnership'". France 24. 1 October 2021.

- ^ France, U.K., Partners Say Russia-Backed Wagner Deployed in Mali

Mali: West condemns Russian mercenaries 'deployment' - ^ Munshi, Neil. "How France lost Mali: failure to quell jihadi threat opens door to Russia". Financial Times. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ "Mali denies deployment of Russian mercenaries from Wagner Group". France 24. 25 December 2021.

- ^ "Flight paths, satellite images indicate Russia is deploying mercenaries in Mali". The Observers – France 24. 4 January 2022.

- ^ a b "Russian military advisors arrive in Mali after French troop reduction". France 24. 7 January 2022.

- ^ "French official says 300–400 Russian mercenaries operate in Mali". news.yahoo.com. 11 January 2022.

- ^ "Russian mercenaries in Mali : Photos show Wagner operatives in Segou". France 24. 11 January 2022.

- ^ "Russian forces deployed at former French base in Mali!". 15 January 2022.

- ^ a b "Small bands of mercenaries extend Russia's reach in Africa". The Economist. 15 January 2022. Archived from the original on 16 January 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ "US army confirms Russian mercenaries in Mali". France 24. 21 January 2022.

- ^ Gramer, Colum Lynch, Amy Mackinnon, Robbie (14 April 2022). "Russia Flounders in Ukraine but Doubles Down in Mali".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Malian, foreign soldiers allegedly killed hundreds in town siege -rights group". news.yahoo.com. 5 April 2022.

- ^ "Russian mercenaries and Mali army accused of killing 300 civilians". the Guardian. 5 April 2022.

- ^ "Mali: Massacre by Army, Foreign Soldiers". Human Rights Watch. 5 April 2022. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- ^ "First Russian 'adviser' confirmed killed in Mali blast, report". www.aljazeera.com.

- ^ "France says it has evidence Russia tried to frame it with mass graves in Mali". The Week. 22 April 2022.

- ^ "Al-Qaida-linked group in Mali says it has captured Russians". news.yahoo.com. 25 April 2022.

- ^ "Russia's Wagner group in Mali spurs refugee spike in Mauritania". Al Jazeera. 28 June 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "US sanctions Mali's defence minister, officials over Wagner ties". Al Jazeera.

- ^ "Mali asks United Nations to withdraw peacekeeping force". Reuters. 16 June 2023. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ "UN in Mali: We respect government's decision for mission withdrawal". africarenewal. 6 July 2023. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ "Mali: Armed groups pull out of peace talks". DW News. Retrieved 2023-04-13.

- ^ "Mali's Azawad movements unite in a bid to pressure the ruling junta". Africanews. 9 February 2023. Retrieved 2023-04-13.

- ^ "Last remaining Malian air force Sukhoi Su-25 aircraft crash". Military Africa. 11 September 2023. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ "An Mi-8 helicopter carrying soldiers from the Wagner PMC was shot down in Mali". Avia. 15 September 2023. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ "Sahel: Army-Tuareg war reignites in north Mali". The North Africa Journal. 2023-09-13. Retrieved 2023-09-17.

- ^ "Mali: les rebelles du CSP attaquent et se retirent du camp militaire de Dioura". RFI (in French). 2023-09-29. Retrieved 2023-10-01.

- ^ Presse, AFP-Agence France. "Mali Separatists Claim Deadly Attack Against Army". www.barrons.com. Retrieved 2023-10-01.

- ^ "Mali Tuareg rebels claim military base following clashes on Sunday". Reuters. 2023-10-01. Retrieved 2023-10-01.

- ^ "Mali's northern rebels claim control of military camp". Reuters. 2023-10-04. Retrieved 2023-10-04.

- ^ "Mali redeploys troops to northeastern rebel stronghold". France 24. 2023-10-02. Retrieved 2023-10-04.

- ^ AfricaNews (2023-10-04). "Mali: army and rebels move closer to a crucial confrontation". Africanews. Retrieved 2023-10-04.

- ^ "New clashes erupt between the Malian military and separatist rebels as a security crisis deepens". AP News. 2023-10-06. Retrieved 2023-10-07.

- ^ Presse, AFP-Agence France. "Mali Junta Plans Takeover Of Key UN Camp In Rebel North". www.barrons.com. Retrieved 2023-10-09.

- ^ UN peacekeepers leaving two more camps in tense northern Mali

- ^ a b UN Expedites Withdrawal of Peacekeepers from Northern Mali Camp

- ^ UN departs new base in Mali's tense Kidal region

- ^ Tuareg Rebels Battle Mali Military, Wagner Group Mercenaries

- ^ Mali army seizes key rebel northern stronghold Kidal

- ^ First photos of Wagner Group operating in Mali hit social media

- ^ Malian army captures Kidal

- ^ Mali: Wagner flies flag over Kidal

- ^ "L'armée malienne arrive à Inafarak, près de la frontière algérienne". RFI (in French). 2024-07-23. Retrieved 2024-07-30.

- ^ Bridger, Bianca (29 July 2024). "Tuaregs, JNIM Inflict Major Losses on Malian, Russian Forces". Atlas News. Retrieved 29 July 2024.

- ^ Meyer, Henry; Hoije, Katarina (2024-07-29). "Russia's Wagner Suffers Most Casualties Since Deploying to Mali". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2024-07-29.

- ^ "Dozens of Russian mercenaries killed in rebel ambush in Mali, in their worst known loss in Africa". CNN. 2024-07-29. Retrieved 2024-07-30.

- ^ "Burkina Faso army says it has deposed President Kabore". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ "Burkina Faso military says it has seized power". BBC News. 24 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ "Who is Paul-Henri Damiba, leader of the Burkina Faso coup?". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ a b Walsh, Declan (25 January 2022). "After Coup in Burkina Faso, Protesters Turn to Russia for Help". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Marsi, Federica. "Burkina Faso: Military coup prompts fears of further instability". www.aljazeera.com.

- ^ "Burkina Faso coup: Why soldiers have overthrown President Kaboré". BBC News. 25 January 2022.

- ^ "Pro-Russia Sentiment Grows in Burkina Faso After Coup". VOA. 28 January 2022.

- ^ a b "US Aware of Allegations of Russian Links to Burkinabe Coup". VOA. 27 January 2022.

- ^ Obaji, Philip Jr. (25 January 2022). "African President Was Ousted Just Weeks After Refusing to Pay Russian Paramilitaries". The Daily Beast – via www.thedailybeast.com.

- ^ Thiam Ndiaga; Anne Mimault (30 September 2022). "Burkina Faso army captain announces overthrow of military government". Reuters. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ Peltier, Elian (2 October 2022). "In Burkina Faso, the Man Who Once Led a Coup is Ousted by One". The New York Times.

- ^ McAllister, Edward (4 October 2022). "Who is Ibrahim Traore, the soldier behind Burkina Faso's latest coup?". Reuters.

- ^ a b Walsh, Declan (2023-03-19). "A 'New Cold War' Looms in Africa as U.S. Pushes Against Russian Gains". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-03-22.

- ^ "Wagner Group: Burkina Faso anger over Russian mercenary link". BBC News. 16 December 2022. Retrieved 2022-12-16.

- ^ "Burkina Faso contracts Russian mercenaries, alleges Ghana". AP NEWS. 15 December 2022.

- ^ "Burkina Faso denies paying Russia's Wagner group with mine rights". www.aljazeera.com.

- ^ Kennedy, Niamh (22 January 2023). "Burkina Faso's military government demands French troops leave the country within one month". CNN.

- ^ "France agrees to withdraw troops from Burkina Faso within a month". www.aljazeera.com.

- ^ Burkina Faso marks official end of French military operations on its soil

- ^ Hoije, Katarina (25 January 2024). "Russian Troops Begin Burkina Faso Deployment to Bolster Security". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2 August 2024.

- ^ "Au Burkina Faso, la première base militaire russe d'Africa Corps". Le Monde.fr (in French). 6 March 2024. Retrieved 2024-03-08.

- ^ Faucon, Benoit (23 February 2023). "WSJ News Exclusive | U.S. Intelligence Points to Wagner Plot Against Key Western Ally in Africa". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2023-03-22.