Water cure (torture)

Water cure is a form of torture in which the victim is forced to drink large quantities of water in a short time, resulting in gastric distension, water intoxication, and possibly death.[1][2][3]

Often the victim has the mouth forced or wedged open, the nose closed with pincers and a funnel or strip of cloth forced down the throat. The victim has to drink all the water (or other liquids such as bile or urine) poured into the funnel to avoid drowning. The stomach fills until near bursting, swelling up in the process and is sometimes beaten until the victim vomits and the torture begins again.

While this use of water as a form of torture is documented back to at least the 15th century,[4] the first use of the phrase water cure in this sense is indirectly dated to around 1898, by U.S. soldiers in the Spanish–American War,[5][a] after the phrase had been introduced to America in the mid-19th century in the therapeutic sense, which was in widespread use.[8] Indeed, while the sense of the phrase water cure as a method of torture was by 1900–1902 established in the U.S. Army,[9][10] with a conscious sense of irony,[11] this sense was not in widespread use. Webster's 1913 dictionary cited only the therapeutic sense.[12]

Torture that makes use of water still exists under the name of waterboarding. In this variation, emphasis is placed on inducing the sensation of drowning rather than forcing the individual to consume, and subsequently regurgitate, large quantities of water.

Historical uses

[edit]East Indies

[edit]The use of the water cure by the Dutch in the East-Indies is documented by the English merchants of the East India Company after the Amboyna massacre in February 1623 (O. S.). The procedure is described in great detail by the survivors of the incident:[13]

The manner of his torture was as follows: First they hoisted him up by the hands with a cord on a large door, where they made him fast upon two staples of iron, fixed on both sides, at the top of the door posts, having his hands one from the other as wide as they could stretch. Being thus made fast, his feet hung some two foot from the ground; which also they stretched asunder as far as they would stretch, and so made them fast beneath unto the door trees on each side. Then they bound a cloth about his neck and face so close, that little or no water could go by. That done, they poured the water softly upon his head until the cloth was full, up to the mouth and nostrils, and somewhat higher; so that he could not draw breath, but he must with all suck in the water: which being still continued to be poured in softly, forced all his inward parts, come out of his nose, ears, eyes, and often as it were stifling and choking him, at length took away his breath, and brought him to a swoon or fainting. Then they took him quickly down, and made him vomit up the water. Being a little recovered, they trussed him up again, and poured water as before, taking him down as soon as he seemed to be stifled. In this manner they handled him three or four several times with water, until his body was swollen twice or thrice as big as before, his cheeks like great bladders, and his eyes staring and strutting out beyond his forehead.

France

[edit]

Water torture was used extensively and legally by the courts of France from the Middle Ages to the 17th and 18th centuries. It was known as being put to "the question", with the ordinary question involving the forcing of one gallon (eight pints or approximately 3.6 litres) of water into the stomach and the extraordinary question involving the forcing of two gallons (sixteen pints or approximately 7.3 litres).

The French poet and criminal François Villon was subjected to this torture in 1461.[14] Jean Calas suffered this torture before being broken on the wheel in 1762.[15] The true case of the Marquise of Brinvilliers was reported in fiction by Arthur Conan Doyle in "The Leather Funnel", by Alexandre Dumas, père, in The Marquise de Brinvilliers[16] and by Émile Gaboriau in Intrigues of a Poisoner.[17]

Germany

[edit]A form of water cure known as the Swedish drink was used by various international troops against the German population during the Thirty Years' War.

Spain

[edit]Water cure was among the forms of torture used by the Spanish Inquisition. The Inquisition at Málaga subjected the Scottish traveller William Lithgow to this torture, among other methods, in 1620. He described his ordeal in Rare Adventures and Painful Peregrinations (1632):[18]

The first and second [measures of water] I gladly received, such was the scorching drought of my tormenting pain, and likewise I had drunk none for three days before. But afterward, at the third charge, perceiving these measures of water to be inflicted upon me as tortures, O strangling tortures! I closed my lips, gainstanding that eager crudelity. Whereat the alcalde enraging, set my teeth asunder with a pair of iron cadges, detaining them there, at every several turn, both mainly and manually; whereupon my hunger-clunged belly waxing great, grew drum-like imbolstered: for it being a suffocating pain, in regard of my head hanging downward, and the water reingorging itself in my throat with a struggling force; it strangled and swallowed up my breath from yowling and groaning.

Before pouring the water, torturers often inserted an iron prong (known as the bostezo) into a victim's mouth to keep it open, as well as a strip of linen (known as the toca) on which the victim would choke and suffocate while swallowing the water.[19]

United States

[edit]

The water cure was brought to the Philippines during Spanish colonial rule, and passed on to Americans by Filipinos in 1899.[20]

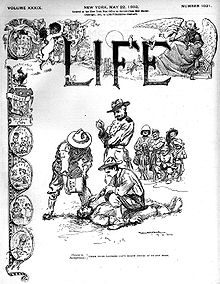

Philippine–American War

[edit]

The water cure was among the forms of torture used by American soldiers on Filipinos during the Philippine–American War.[21][22][23] President Theodore Roosevelt privately assured a friend that the water cure was "an old Filipino method of mild torture. Nobody was seriously damaged whereas the Filipinos had inflicted incredible tortures on our people."[24] The president went further, stating, "Nevertheless, torture is not a thing that we can tolerate." However, a report at the time noted its lethality; "a soldier who was with General Funston had stated that he helped to administer the water cure to one hundred and sixty natives, all but twenty-six of whom died".[25] See the Lodge Committee for detailed testimony of the use of the water cure.

U.S. Army Major Edwin Forbes Glenn was suspended from command for one month and fined $50 for using the water cure in an incident which occurred on November 27, 1900. The Army judge advocate said the charges constituted "resort to torture with a view to extort a confession" and recommended disapproval because "the United States cannot afford to sanction the addition of torture".[9][b]

Lieutenant Grover Flint said during the Philippine–American War:

A man is thrown down on his back and three or four men sit or stand on his arms and legs and hold him down; and either a gun barrel or a rifle barrel or a carbine barrel or a stick as big as a belaying pin,—that is, with an inch circumference,—is simply thrust into his jaws and his jaws are thrust back, and, if possible, a wooden log or stone is put under his head or neck, so he can be held more firmly. In the case of very old men I have seen their teeth fall out,—I mean when it was done a little roughly. He is simply held down and then water is poured onto his face down his throat and nose from a jar; and that is kept up until the man gives some sign or becomes unconscious. And, when he becomes unconscious, he is simply rolled aside and he is allowed to come to. In almost every case the men have been a little roughly handled. They were rolled aside rudely, so that water was expelled. A man suffers tremendously, there is no doubt about it. His sufferings must be that of a man who is drowning, but cannot drown.[26]

In his book The Forging of the American Empire Sidney Lens recounted:

A reporter for the New York Evening Post (April 8, 1902) gave some harrowing details. The native, he said, is thrown on the ground, his arms and legs pinned down, and head partially raised "so as to make pouring in the water an easier matter". If the prisoner tries to keep his mouth closed, his nose is pinched to cut off the air and force him to open his mouth, or a bamboo stick is put in the opening. In this way water is steadily poured in, one, two, three, four, five gallons, until the body becomes "an object frightful to contemplate". In this condition, of course, speech is impossible, so the water is squeezed out of the victim, sometimes naturally, and sometimes—as a young soldier with a smile told the correspondent—"we jump on them to get it out quick." One or two such treatments and the prisoner either talks or dies.[1]

Police

[edit]The use of "third-degree interrogation" techniques in order to compel confession, ranging from "psychological duress such as prolonged confinement to extreme violence and torture", was widespread in early American policing as late as the 1930s. Author Daniel G. Lassiter classified the water cure as "orchestrated physical abuse", and described the police technique as a "modern-day variation of the method of water torture that was popular during the Middle Ages." The technique employed by the police involved either holding the head in water until almost drowning, or laying on the back and forcing water into the mouth or nostrils.[27]: 47 Such techniques were classified as "'covert' third degree torture" since they left no signs of physical abuse, and became popular after 1910 when the direct application of physical violence in order to force a confession became a media issue and some courts began to deny obviously compelled confessions.[28]: 42 The publication of this information in 1931 as part of the Wickersham Commission's "Report on Lawlessness in Law Enforcement" led to a decline in the use of third degree police interrogation techniques in the 1930s and 1940s.[28]: 38

Japan

[edit]During World War II, water cure was among the forms of torture used by Japanese troops (especially the Kenpeitai) in occupied territory. A report from the postwar International Military Tribunal for the Far East summarized it as follows:

The so-called "water treatment" was commonly used. The victim was bound or otherwise secured in a prone position; and water was forced through his mouth and nostrils into his lungs and stomach until he lost consciousness. Pressure was then applied, sometimes by jumping upon his abdomen to force the water out. The usual practice was to revive the victim and successively repeat the process.[29]

Chase J. Nielsen, who was captured in the Doolittle Raid, testified at the trial of his captors, "I was given several types of torture … I was given what they call the water cure" and it felt "more or less like I was drowning, just gasping between life and death."[5]

Philippines

[edit]The water cure has had a long history of use during Philippines' colonial history, having been used during the Spanish, American, and Japanese occupations. In the Philippine–American War of 1898-1902, the United States Army tracked guerilla forces using the "water cure", torturing informants until they talked. Back in the U.S., opposition to the war grew, as did bitter debates on the morality and legality of the technique.[30]

After Philippine Independence in 1945, the most notable instances of its use by the Philippine government was by the dictatorship of former President Ferdinand Marcos.[31][32]

Marcos regime

[edit]The water cure was one of the torture methods most used frequently by the Marcos regime in the Philippines from 1965 to 1986, whose torturers referred to the practice as NAWASA sessions—a reference to the National Waterworks and Sewerage Authority which supplied water to the Metro Manila area at the time.[32][33] The practice was widely documented by organizations such as the Task Force Detainees of the Philippines, the World Council of Churches, the International Commission of Jurists, among others.[31] Notable survivors of the torture include Loretta Ann Rosales, who eventually became the Chair of the Philippines' Commission on Human Rights,[31] and Maria Elena Ang, who was a 23-year-old journalism student of the University of the Philippines at the time of her torture.[32][34]

See also

[edit]- List of unusual deaths

- The dose makes the poison

- Force feeding

- Waterboarding

- Water intoxication

- Water torture

Notes

[edit]- ^ The late-19th-century expropriation of the term water cure, already in use in the therapeutic sense, to denote the polar opposite of therapy, namely torture, has the hallmark of arising in the sense of irony. This would be in keeping with some of the reactions to water cure therapy and its promotion, which included not only criticism, but also parody and satire.[6][7]

- ^ A 2008 article on the National Public Radio website mistakenly asserted that this incident occurred during the Spanish–American War.[4] However, that war ended with the signing of the Treaty of Paris on December 10, 1898.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Sidney Lens (2003). The Forging of the American Empire: From the Revolution to Vietnam: A History of U.S. Imperialism. Pluto Press. ISBN 0-7453-2100-3.

- ^ Elaine Korry (2005-11-14). "A Fraternity Hazing Gone Wrong". National Public Radio.

- ^ Tom Zeller Jr. (2007-01-15). "Too High a Price for a Wii". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Eric Weiner (2007-11-03). "Waterboarding: A Tortured History". National Public Radio.

- ^ a b Evan Wallach (2007-11-02). "Waterboarding Used to Be a Crime". Washington Post.

- ^ Thomas Hood, ed. (1842). "Review of Hydropathy, or The Cold Water Cure". The Monthly Magazine and Humourist. Vol. 64. London: Henry Colburn. pp. 432–435.

- ^ The Larks (1897). The Shakespeare Water Cure: A Burlesque Comedy in Three Acts. New York: Harold Roorbach. Retrieved 6 December 2009. Full text at Internet Archive (archive.org)

- ^ Metcalfe, Richard (1898). Life of Vincent Priessnitz, Founder of Hydropathy. London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co., Ltd. Retrieved 3 December 2009. Full text at Internet Archive (archive.org)

- ^ a b Paul Kramer (February 25, 2008). "The Water Cure". The New Yorker. Retrieved 6 December 2009. (Article describing the U.S. military expropriation of 'water cure' to denote a form of torture, with acknowledgement by one accused (p.3) of the difference in popular understanding, from the sense used by the military)

- ^ Sidney Lens (2003), p.188

- ^ Sturtz, Homer Clyde (1907). "The water cure from a missionary point of view". from the Central Christian Advocate, Kansas, June 4, 1902. Kansas. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Water cure definition per Webster's 1913 dictionary". Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- ^ A True Relation of the late unjust, cruel and barbarous proceedings against the English at Amboyna. British Library: John Skinner of the East India Company. 1624.

- ^ Jannet, Pierre, ed (2004). Preface. Oeuvres complètes de François Villon. "En 1457, il était dans les prisons du Châtelet, et le Parlement, après lui avoir fait appliquer la question de l'eau, le condamnait à mort."

- ^ Harvey, Simon, ed (2000). Note 8 to Chapter 1. Voltaire: Treatise on Tolerance. Cambridge University Press, p. 8: "the Question Extraordinary involved suffocation, the victim's nose pinched while great quantities of water were poured through a funnel into his throat. Records show that Jean Calas withstood this torment without once submitting to the torturers' threats, and consistently denied that any crime had taken place."

- ^ The Marquise de Brinvilliers at Intratext

- ^ Intrigues of a Poisoner

- ^ Hadfield, Andrew, ed. (2001). Amazons, Savages, and Machiavels. Oxford University Press. p. 114. Spellings have been modernized.

- ^ Lea, Henry Charles (1906-7). A History of the Inquisition of Spain. Volume 3, Book 6, Chapter 7

- ^ Stephen Kinzer (2017), The True Flag: Theodore Roosevelt, Mark Twain, and the Birth of American Empire, Henry Holt and Company, p. 150, ISBN 978-1-62779-217-2

- ^ Miller, Stuart Creighton (1982). "Benevolent Assimilation" The American Conquest of the Philippines, 1899–1903. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-02697-8.

Future President William Howard Taft conceded under questioning at the Lodge Committee that the "so called water cure" had been used on some occasions to extract information. Quoted from S. Doc. 331, 57 Congressional 1 Session (1903), page 1767–1768

: 213 - ^ Welch, Richard E. (1973). "American Autocracies in the Philippines: The Indictment and the Response". Pacific Historical Review. 43 (2): 233–253. doi:10.2307/3637551. JSTOR 3637551.

- ^ Paul A. Kramer (2006). "The Blood of Government" Race, Empire, the United States, and the Philippines. University of North Caroline Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-5653-6. On page 142 there is a picture from the Jonathan Best Collection depicting American soldiers and their Macabebe allies performing water cure during the American-Philippine War.

- ^ Elting Morison, ed. (1902-07-19). "Private letter from Roosevelt to Speck von Sternberg". The Letters of Theodore Roosevelt. 3: 297–98.

- ^ Storey, Moorfield; Codman, Julian (1902). – via Wikisource.

- ^ Miller, Stuart Creighton (1982). "Benevolent Assimilation" The American Conquest of the Philippines, 1899–1903. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-02697-8. p. 218; Told of "Water Cure" Given to Filipinos. Witness Went Into Details Before Senate Committee on the Philippines. The New York Times, Feb. 25, 1902, p. 3

- ^ G. Daniel Lassiter (2004). Interrogations, Confessions, and Entrapment. Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 0-306-48470-6.

- ^ a b "From coercion to deception: the changing nature of police interrogation in America". Crime, Law and Social Change. 18. Kluwer Academic Publishers. 1992.

- ^ Judgement of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (1948). Part B, Chapter VIII, p. 1059.

- ^ Hasian, Marouf Jr. (2012). "The Philippine–American War and the American Debates about the Necessity and Legality of the 'Water Cure,' 1901–1903". Journal of International and Intercultural Communication. 5 (2): 106–123. doi:10.1080/17513057.2011.650184.

- ^ a b c Marcelo, Elisabeth (21 August 2016). "ORAL ARGUMENTS ON HERO'S BURIAL: Torture victims tell SC of tales of horror under Marcos' Martial Law". GMA News Online. Archived from the original on 2017-12-29. Retrieved 2018-04-13.

- ^ a b c McCoy, Alfred (2007-04-01). A Question of Torture: CIA Interrogation, from the Cold War to the War on Terror. Henry Holt and Company. p. 83. ISBN 9781429900683.

maria%20elena%20ang%20water.

- ^ Garcia, Myles (31 March 2016). Thirty Years Later ... Catching Up with the Marcos-Era Crimes. Quezon City: MAG Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4566-2650-1. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- ^ Sison, Shakira Andrea (2015-10-14). "Martial Law stories young people need to hear – Bantayog ng mga Bayani". Bantayog ng mga Bayani. Archived from the original on 2018-04-13. Retrieved 2018-04-13.

External links

[edit]- "Louis of Germany tortures men." – A 14th-century illustration from the Grandes Chroniques de France, reproduced in Chapter 4 of Anne D. Hedeman's The Royal Image (1991).

- "The Water Cure Described" (PDF). The New York Times. May 4, 1902. Retrieved 6 December 2009. (from The New York Times' archive).

- Sturtz, Homer Clyde (1907). "The water cure from a missionary point of view". from the Central Christian Advocate, Kansas, June 4, 1902. Kansas. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) Newspaper article describing the pros and cons on the usage of the water cure method during the Filipino-American War - Paul Kramer (February 25, 2008). "The Water Cure". The New Yorker. Retrieved 6 December 2009. (Detailed article describing the U.S. military expropriation of "water cure" to denote a form of torture).