Weltende (Jakob van Hoddis)

Weltende is a poem by the German poet Jakob van Hoddis, the anagrammatic pseudonym of Hans Davidsohn (1887-1942).[1] The poem is, from its appearing until today, the most famous expressionistic one, though its author has remained quite unknown for a long time, principally in the United States.[2] Van Hoddis was killed in 1942, most likely in the Sobibór extermination camp.[3]

German original and its adaption

[edit]Van Hoddis's poem Weltende has been often translated into English. But most of translations miss rhyme scheme, rhythm, verse form, and in sum the 'foolhardy' spirit of the original. The following adaption by Natias Neutert affords a little generosity on poetic licence (verse 6: "as if they were midges"),[4] but consider all specifications, such as rhyme scheme, masculine and feminine cadences, and principally the spirit of the original:[neutrality is disputed]

|

Weltende Dem Bürger fliegt vom spitzen Kopf der Hut, Der Sturm ist da, die wilden Meere hupfen |

World's End The burgher’s hat flies away in a trice. The storm is here, wuthering seas are hopping |

Creation, first and later publications

[edit]

The poem, probably written in 1910,[5] was first published at 11. January in 1911 in «Der Demokrat», a free-thinking Berlin magazine, almost four years before the outbreak of the First World War.[6] At the end of 1919 and the start of 1920 it was published in the anthology of expressionist poetry titled Menschheitsdämmerung by Kurt Pinthus, an explosive pioneering work of all those experiments, and till today still the representative collection of Expressionism.[7]

Figurehead of the movement

[edit]The two stanzas "entered the then literary scene with a beat of a kettledrum and advanced to an epoch-making 'earworm' among all Expressionist poems, and it was taken as family crest in a trice," as the German poet and translator Natias Neutert comments on van Hoddis' poem in a note.[8] Therefore, Jattie Enklaar/Hans Ester/Evelyne Tax class van Hoddis' Weltende as a "keypoem".[9] To get an idea of the impact of these eight lines, a contemporary witness may called and quoted: The writer Johannes R. Becher, who later became Minister of Culture of the GDR, described the poem in 1957, one year before his death, as "Marseillaise of expressionistic rebellion"[10] and wrote with sustaining deep admiration: "These two stanzas, o these eight lines seemed to transform us into other people, they lifted us from a world of dull bourgeoisie that we despised and from which we did not know how we should leave."[11] "It was a feeling of superiority and freedom, what these verses were able to awaken,"[12] as the German literary scientist Helmut Hornbogen classified the effect.

Literary historical classifications

[edit]

Genre

[edit]The poem Weltende is assigned to the genre of early expressionistic Großstadtlyrik (big city poetry).[13] The genre traces back, as the Germanist Hugo Friedrich[14] describes, to the forerunners Arthur Rimbaud and Charles Baudelaire, and to their fight for "...being absolutely modern...“ (Rimbaud), both poets practised a symbiosis of literature and life.[15]

Formatwise

[edit]Formally seen, the poem is held more conventionally as other expressionistic poems with their break of rules of grammar and with a lot of extraordinary expressive neologisms.[16]

Structure of the poem

[edit]The poem is constructed out of two stanzas with always four verses. The rhyming scheme in the first stanza has an embracing rhyme (ABBA), in the second one a cross rhyme (CDCD). Metrical seen an iambic pentameter having some irregularities in the second stanza. The first one is accentuated with masculine cadences, the second one with female cadences.

Title, topic, motif

[edit]

The title Weltende means the same as end of the world or end time, but van Hoddis used it ironically, because the proper meaning is natural catastrophe, which is actually the poem's subject matter. The main motif is the struggle between two opposing forces: the first nature and the so-called second nature, build up by mankind with the material of the first one.[17] In a nutshell: nature vs. society.

Interpretation

[edit]

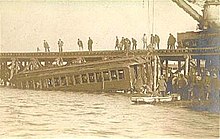

The poem can be taken as a foreboding of modern actor-network theory.[18] There is no lyrical "I" who acts, but the actors are the elements of nature. At the beginning, for example, wind blows the hats off citizens' heads. Then the wild seas, according to the German poet Peter Rühmkorf, "board [pirate-like] the land like a readily capturable sandbox and treat humankind's proud work as a giant toy."[19]

That roof tilers "break in two" (verse 3) can be taken as a hint that van Hoddis deals with a dichotomy. On the one hand, there is a serious tone in the apocalyptic title and some of the incidents described; on the other, the poem overall is playful, ironic, detached. Rühmkorf refers to this indifferent catastrophe as a "vest pocket apocalypse" (Westentaschenapokalypse).[20]

Versions and pitfalls of translating

[edit]To have introduced van Hoddis’ poem Weltende into the Anglo-American literary scene has been the merit of Michael Hamburger, British poet and translator.[21] However, his version breaks the given rhyme scheme of the original's first stanza (the embracing rhyme) and fails to capture its female cadences in the second stanza. And the use of the word jetties—even if they are „big“— instead of the word Deiche (dams), extenuates the original's power of imagery impermissibly .[22]

|

Weltende Dem Bürger fliegt vom spitzen Kopf der Hut, Der Sturm ist da, die wilden Meere hupfen |

End Of The World From pointed pates hats fly into the blue, The storm has come, the seas run wild and skip |

Hamburger's version was published in 1977. More than twenty years later the anthology German 20th Century Poetry was published by Reinhold Grimm and Irmgard Hunt.[23] Within one finds a nearly line-by-line-takeover of Hamburger's version by Irmgard Hunt. Only six words—less than ten percent— are exchanged.[24]

From pointed pates hats fly into the blue,

All winds resound as so with muffled cries.

Steeplejacks fall from roofs and break in two,

And on the coasts—we read —the tides rise high.

The storm is here, the seas run wild and skip

On land, crushing thick bulwarks there.

Most people have a cold, their noses drip.

Trains tumble from the bridges everywhere.

Others versions, such as Christopher Middleton's, Richard John Ascárate's or Rolf-Peter Wille's demonstrate the widely scope of translating, but in some way or other they all fail the original's versification, its imagery or its spirit, as any comparison suggests.[25][26][27]

Works

[edit]Only one single book, titled Weltende, was published during van Hoddis’ lifetime, in 1918. The following are available editions:

- Jakob van Hoddis. Dichtungen und Briefe (poetry and letters). Ed. by Regina Nörtemann. Wallstein, Göttingen 1987.

- Jakob van Hoddis, Weltende. Gesammelte Dichtungen (collected poetry). Ed. by Paul Pörtner, Peter Schifferli Verlag Die Arche, Zürich 1958.

See also

[edit]External links

[edit]Literature

[edit]- Ralf Georg Bogner: Einführung in die Literatur des Expressionismus. Einführungen Germanistik, ed. by Gunter E. Grimm/Klaus-Michael Bogdal. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2005. ISBN 3-534-16901-8

- Natias Neutert: Foolnotes. Very Best German Poems. Bilingual Edition. Smith Gallery Booklet, Soho New York 1980.

- Language and Culture: German Expressionist Poetry in Franz Pfemfert’s Journal Die Aktion (1911-1919) . School of Languages and Cultures in the Faculty of Arts, Sydney University, 17 June 2011.

- Karl Riha: „Dem Bürger fliegt vom spitzen Kopf der Hut“. In: Harald Hartung (ed): Gedichte und Interpretationen, vol. 5. Reclam Verlag, Stuttgart 1983, p. 118-125. ISBN 3-15-007894-6.

- Thomas Schmid: Dem Bürger fliegt vom spitzen Kopf der Hut Dem Bürger fliegt vom spitzen Kopf der Hut, Artikel von Thomas Schmid in Die Welt, 8. Januar 2011.

References

[edit]- ^ Cf. Department of German, Berkeley University http://german.berkeley.edu/leselust/poetry-corner/jakob-von-hoddis-weltende/

- ^ Cf. Neil H. Donahue: A Companion to the Literature of German Expressionism. p. 15, 332.

- ^ Cf. German Biography http://www.deutsche-biographie.de/sfz39374.html

- ^ Cf. Natias Neutert: Foolnotes. Very Best German Poems. Bilingual Edition. Smith Gallery Booklet, Soho New York 1980, p. 18.

- ^ The exactly year is not determinable because the surviving manuscript has no date. Cf. Jacob van Hoddis: Dichtungen und Briefe. Ed. by Regina Nörtemann, Zürich 1987, p. 34. ISBN 371602046X / 3-7160-2046-X

- ^ Cf. Theo Buck: Streifzüge durch die Poesie. Von Klopstock bis Celan. Gedichte und Interpretationen. Böhlau Verlag Köln/Weimar/Wien 2010, p. 191. ISBN 978-3-412-20533-1

- ^ Kurt Pinthus (ed.): Menschheitsdämmerung. Ein Dokument des Expressionismus. Rowohlt Taschenbuch, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1964. ISBN 9783499450556

- ^ Cf. Natias Neutert: Foolnotes. Smith Gallery Booklet, New York 1980, p. 18.

- ^ Cf. Jattie Enklaar/Hans Ester/Evelyne Tax: Schlüsselgedichte: deutsche Lyrik durch die Jahrhunderte von Walther von bis Paul Celan. Verlag Könighausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2009, p. 206.

- ^ Johannes R. Becher: Bemühungen. Macht der Poesie. Das poetische Prinzip, vol. II, Redaktion Ingeborg Ortloff, Nachwort Hermann Kähler, Aufbau Verlag Berlin/Weimar 1972, p. 339 f

- ^ Johannes R. Becher: Bemühungen. Macht der Poesie. Das poetische Prinzip, vol. II, Redaktion Ingeborg Ortloff, Nachwort Hermann Kähler, Aufbau Verlag Berlin/Weimar 1972, p. 339 f

- ^ Cf. Helmut Hornbogen: Jakob van Hoddis. Die Odyssee eines Verschollenen. Carl Hanser Verlag, München/Wien 1986, p. 73. ISBN 3-446-14401-3

- ^ Cf. Bernd Läufer: Jakob van Hoddis: der «Varieté»-Zyklus. Ein Beitrag zur Erforschung der frühexpressionistischen Großstadtlyrik. Literarhistorische Untersuchungen ed. by Theo Buck, no. 20. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main/Berlin/Bern/New York/Paris/Wien 1992, pp. 17-25. ISBN 3-631-44941-0

- ^ Cf. Hugo Friedrich: Die Struktur der modernen Lyrik . Von Baudelaire bis zur Gegenwart. Rowohlts Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg, 1962. ISBN 9783499550256

- ^ Cf. Svetlana Boym: Death in Quotation Marks. Cultural Myths of the Modern Poet. Harvard University Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts/London1991, p. 113. ISBN 0-674-19427-6

- ^ Cf. Heinz Peter Dürsteler: Sprachliche Neuschöpfungen im Expressionismus. Thun 1954.

- ^ Cf. Neil Smith: Uneven Development. Nature, Capital, and the Production of Space. Third edition, with a new afterword by the author and a foreword by David Harvey. The University of Georgia Press, Athens, London 2008, pp. 32-33. ISBN 978-0-8203-3590-2

- ^ Cf. John Law/John Hassard (ed): Actor Network Theory and after. Blackwell Publishers, Oxford/Malden 1999. ISBN 978-0631211945

- ^ Cf. Peter Rühmkorf: Zur Teilnahmslosigkeit erstarrt. In: Gedichte und Interpretationen, Frankfurter Anthologie, vol. II, ed. and with an afterword by Marcel Reich-Ranicki. Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1977, p. 129. ISBN 345805023X

- ^ Cf. Peter Rühmkorf: Zur Teilnahmslosigkeit erstarrt. In: Gedichte und Interpretationen, Frankfurter Anthologie, vol. II, ed. and with an afterword by Marcel Reich-Ranicki. Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1977, p. 129. ISBN 345805023X

- ^ German Poetry 1910-1975. An Anthology in German and English. Selected, translated and introduced by Michael Hamburger. Carcanet New Press/Manchester, United Kingdom in 1977, p. 83.

- ^ Cf. Natias Neutert: Foolnotes. Smith Gallery Booklet, New York 1980, pp. 18 f.

- ^ German 20th Century Poetry ed. by Reinhold Grimm/Irmgard Hunt. The German Library, vol. 69. Continuum International Publishing Group New York/London 2001. ISBN 0-8264-1312-9

- ^ Loco citato, p. 44:

- ^ Cf. Christopher Middleton’s version in: The Faber Book of 20th-Century German Poems. Ed. by Michael Hofmann. Faber and Faber, London/New York 2005, p. 41. ISBN 0-571-19703-5-

- ^ Cf. Richard John Ascárate’s version. http://german.berkeley.edu/leselust/poetry-corner/jakob-von-hoddis-weltende/

- ^ Cf. Rolf-Peter Wille’s version. http://hoddisend.blogspot.dk