William Grinfield

William Grinfield | |

|---|---|

William Grinfield by an unknown artist | |

| Nickname(s) | Grinney[1] |

| Born | c.1743 Wiltshire |

| Died | (aged 58) Barbados |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service | British Army |

| Years of service | 1760–1803 |

| Rank | General |

| Unit | 3rd Foot Guards |

| Commands | 1st Battalion 3rd Foot Guards Sub-District, Southern District North-West District Midland District Eastern District Windward and Leeward Islands |

| Battles / wars | |

General William Grinfield (c.1743–19 October 1803) was a British Army officer who served during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. Grinfield joined the 3rd Regiment of Foot Guards in 1760 and was promoted through the ranks, becoming a major in the regiment in 1786. In 1793 his regiment joined the Flanders Campaign, fighting at the siege of Valenciennes and Battle of Lincelles, during which time he was promoted to lieutenant-colonel. Having held a higher army-wide rank than he did regimental rank, Grinfield was promoted by seniority to major-general later in the same year.

Grinfield continued with the 3rd Guards until 1795 when he was given a command within the Southern Military District, also becoming colonel of the 86th Regiment of Foot. He went on to command the North-West Military District before in 1798 being promoted to lieutenant-general, and in 1801 receiving command of the Midland Military District. In the following year he was made Commander-in-Chief of the Forces in the Windward and Leeward Islands. In this role he attacked French and Dutch colonies at the beginning of the Napoleonic Wars in 1803, capturing Saint Lucia, Tobago, Demerara, Essequibo, and Berbice. Promoted to general on 1 October of the same year, he died of yellow fever at Barbados only eighteen days later, aged 58.

Military career

[edit]Early service

[edit]Born in Wiltshire in about 1743, William Grinfield was the son of William Grinfield, or Greenfield, a politician who unsuccessfully stood to become member of parliament for Marlborough in 1737.[1][2][3] His mother was a niece of the politician John Smith. Grinfield was educated at Westminster School and then joined the British Army in 1760, becoming an ensign in the 3rd Regiment of Foot Guards on 1 September.[1][4][5]

Grinfield was promoted to lieutenant (regimental rank) and captain (army rank) on 9 December 1767,[Note 1] and then to captain and lieutenant-colonel respectively on 3 February 1776.[7] The American Revolutionary War having begun, in June 1777 Grinfield travelled out to America in command of a draft of guardsmen, returning to England in January the following year.[8] He returned to the conflict in March 1781 when he joined the Composite Guards Regiment serving there. While his services in North America are not recorded in detail, Grinfield was present at the surrender after the Siege of Yorktown on 19 October, and as such military historian S. G. P. Ward suggests prior to this he fought at the Battle of Guilford Court House on 15 March.[1][8]

Battalion command

[edit]Taken prisoner with the rest of the British Army at Yorktown, Grinfield was exchanged in December 1782, having been promoted to colonel (army rank) on 20 November.[1][9][8] Again serving in the 3rd Foot Guards, Grinfield was promoted to the regimental rank of major on 18 April 1786, becoming the junior of the two majors serving in the regiment. He was advanced from Second Major to become First Major on 13 September 1791. In the following year the commanding officer of Grinfield's 1st Battalion, Major-General Gustavus Guydickens, was suspended from his position because of fifty-eight outstanding debts at the Court of King's Bench and a criminal charge of gross indecency. Grinfield took over as commander of the battalion.[1]

Discipline in Grinfield's battalion had been lax under Guydickens, and he set about a campaign to fix this. Described by Ward as "a regime of...oppressive tyranny", Grinfield's superiors requested that he stop disciplining his unit so severely. Little had changed, however, when in March 1793 Grinfield and his battalion, 600 men strong, joined the Guards Brigade to fight in the French Revolutionary War.[1][10][11] Grinfield was singled out for his "personal bravery and ability" while fighting at the siege of Valenciennes between May and July, and in early August was promoted to become lieutenant-colonel of his battalion. This made him a regimental lieutenant-colonel and an army-wide colonel.[10] The promotion came about because Guydickens was still absent, awaiting a court martial for homosexual conduct.[12]

Grinfield subsequently fought with his battalion at the Battle of Lincelles on 18 August .[10] Here he served as second-in-command to Major-General Gerard Lake, who commanded the Guards Brigade. Lake's 1,120 men defeated a French force of 5,000 in the battle.[13] For his conduct, Grinfield was afterwards thanked by the Commander-in-Chief, the Duke of York.[10] York's opinion of Grinfield was not always so positive. Grinfield had continued his oppressive leadership of his battalion, in October having his troops, stationed at Englefontaine:

...be roused by the four o'clock fife

Which wakes up the fags to parade till broad day

And, to Grinney's delight, whistles Morpheus away[1]

In the same month Grinfield was promoted to major-general. Now of a seniority that it might be expected that he could take command of a brigade within York's army on campaign, the Duke considered him "a most terrible inconvenience".[1][7] Grinfield, learning of York's opinion, took it badly and returned to England.[14]

Home general

[edit]

Serving with the 3rd Foot Guards in his regimental rank of lieutenant-colonel, Grinfield continued his harsh disciplinary ways. He was criticised by members of his regiment for "a most brutal and oppressive plan of discipline", with his "unprecedented martinetism" having "discontented the whole regiment".[15] At some point during this period Grinfield was on guard duty at the tiltyard in Horse Guards when he was met by a group of his creditors and sheriff's officers. Instead of agreeing to their demands Grinfield had them surrounded by soldiers and locked in the guardroom. The Lord Chief Justice of the King's Bench, Lord Kenyon, threatened him with contempt of court, at which point Grinfield surrendered to his creditors with "ignominious submission".[14]

On 20 February 1795 Grinfield was given control of the garrison at Dover, with his home in Sidmouth, commanding part of the Southern Military District.[16][17][18][19] He was then made colonel of the 86th Regiment of Foot on 25 March, replacing Lieutenant-General Russell Manners and relinquishing his position as lieutenant-colonel of the 3rd Foot Guards.[20][7]

By June 1798 Grinfield had moved to command the North-West Military District.[21][22] He was then promoted to lieutenant-general later in the year, and in January 1801 was given command of the Midland, or Inland, Military District, consisting of most of Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire with his headquarters in Lichfield.[14][23][24][25] Early in 1802 Grinfield was transferred to command the Eastern Military District, before on 5 June he was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Forces in the Windward and Leeward Islands.[Note 2][14][26]

C-in-C Windward and Leeward Islands

[edit]Preparations for war

[edit]The French Revolutionary Wars had recently ended with the Peace of Amiens. Grinfield replaced Lieutenant-General Sir Thomas Trigge as Commander-in-Chief, inheriting a force of around 10,000 men, of which 3–4,000 were available for offensive military operations.[27] The troops in the West Indies were pre-warned and wary of Grinfield's disciplined ways, which he continued upon arriving at Barbados. "He descended upon them like a thunderbolt", according to Ward, ordering extra evening parades, demanding even surgeons wear full regimental uniforms, and halting the practice of long, drawn out dinners.[14] The British government gave Grinfield early warning in April 1803 that the Peace was going to end, beginning the Napoleonic Wars, and in response Grinfield began to prepare for operations.[28][29][30] He toured all the British West Indies islands and also those belonging to the French in order to understand what he would have to seize in wartime, and brought together supplies and troopships for his men. Word came to the West Indies on 14 June that Britain was again at war with France, and Grinfield was ordered to begin a campaign against the hostile islands.[14][28][29][30]

Working in cooperation with Commodore Samuel Hood, Commander-in-Chief Leeward Islands Station, Grinfield's force set sail from Barbados on 20 June.[29] Among his senior officers Grinfield had Brigadier-General George Prévost as his second-in-command, alongside Brigadier-General Thomas Picton and Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Pakenham.[31][29] The force was 3,149 men strong, including the second battalion of the 1st Regiment of Foot and the 64th, 68th, and 3rd West Indies regiments.[29] While initial orders had expected Grinfield to attack Martinique, this was a heavily defended island that would have required 10,000 men to attack, and so Grinfield and Hood chose to attack other locations.[29][30]

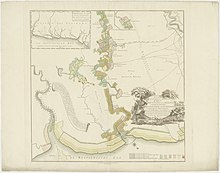

Capture of Saint Lucia and Tobago

[edit]Grinfield first attacked the French island of Saint Lucia.[28] This was to ensure that the French could not continue to resupply and fortify the island. His force landed in Choc Bay on 21 June, and at 5:30 a.m. advanced through the nearby French outposts and captured Castries. The French commander, Brigadier Antoine Noguès, was then requested to surrender, but he refused. In response Grinfield stormed Morne Fortune fort at 4 a.m. the next day.[10][32][33] This attack was made by two columns of troops, commanded respectively by the brigadiers Picton and Robert Brereton, and after half an hour of fighting the fort was taken, with the British suffering 138 casualties. The force took 640 French soldiers prisoner and sent them back to France, although Noguès became friendly with Grinfield and received permission to go to Martinique instead.[34][35]

Brereton was left to hold Saint Lucia with the 68th and three companies of the 3rd West Indies Regiment.[34] Grinfield moved on with the rest of his expedition, attacking Tobago five days later.[34] The island was commanded by Brigadier-General César Berthier, who was forced to surrender on 1 July after Grinfield made a quick advance on his capital Scarborough with two columns of soldiers.[Note 3][10][36][31] Grinfield sent Berthier and his 200 soldiers back to France, having completed his attack without receiving a single casualty.[37][38][35] The capture of Tobago at this stage stopped French plans to reinforce it, which would have seen Berthier build a strong naval depot guarded by a garrison of 1,200 men.[38]

Surrender of the Dutch colonies

[edit]

Having left eight companies from the 1st and another one from the 3rd West Indies as garrison on Tobago, Grinfield returned to Barbados.[39] This was to ensure that his force was not too thinly spread to respond to any French counterattacks from Martinique or Guadeloupe, with Antigua having refused to create a militia to help defend itself.[Note 4][38] The Dutch colonies in the West Indies, nominally controlled by the Batavian Republic, were wary of the bloodshed that might come to them if they were invaded, having been visited by the French colonial governor Victor Hughes in early July, and they requested to Britain that they be peacefully taken over by Grinfield. He received his orders on 10 August to go and accept the surrender of the Dutch governors, and a week later the Batavian Republic joined with France against Britain, making Grinfield's path to capture them more simple. Despite this Grinfield was worried about any further offensive actions, with much of his expeditionary force already used up as garrisons of the newly captured French islands. He requested that 5,000 more men be sent out to supplement his force.[40][39]

Grinfield was promised that a battalion would be sent to him from Gibraltar, but neither this nor any other reinforcements were provided. He waited for any arrivals until the end of August and then decided that an attack had to take place despite his smaller force. He supplemented it with Royal Marines and on 1 September set out again in conjunction with Hood, with his force 1,300 men strong.[41][42] This was mostly made up of the 64th and parts of the 3rd, 7th, and 11th West Indies.[41] Grinfield first sailed to Demerara because he expected that surrender to be entirely peaceful. Arriving on 16 September at Georgetown he sent an offer to the governor. On 19 September his force took control of Demerara and Essequibo without bloodshed, the local commanders having surrendered on board the 22-gun post ship HMS Heureux the day before.[Note 5][10][43][41]

Later in the same day 550 men were sent on to Berbice, which was under the control of a different commander.[10][44] There a flag of truce was organised and a committee was received to surrender the island, but the Dutch garrison commander refused to capitulate without discussion with his officers. Eventually agreement was found and the British took control on 25 September, capturing the 600-strong garrison.[10][45] The operation was completed without loss to the British. Of the 1,500 Dutch soldiers in garrison on the three colonies half of them chose to join Grinfield, becoming the York Light Infantry Volunteers.[41] Grinfield was promoted to general on 1 October.[46]

Death

[edit]What boding omens, on the western gale,

In tearful sympathy, this isle assail?

Why, sad, responsive, doe Britannia sigh?

Has fate decreed a nation's downfall nigh?

Ah! No! But yet a generous people mourn

Their Grinfield dead, from them and glory tornThe verdant laurels, to his eager grasp,

Yield, not relent, his warlike brow to clasp.

Long, vainly, death in battle's storm had tried

To pierce his gallant breast with crimson dyed:

In vain oppos'd the thundering cannon's roar

And glittering steel; he firmly trod the shore –

His country's cause bore down the opposing host,

"My Country, God, and King," his only boast.

Excerpt from Elegy on the death of General Grinfield.[47]

Grinfield returned to Barbados from Georgetown in late September.[48] Throughout this time sickness had been rife in Grinfield's force, with around 700 men having died. Grinfield was not immune to this, and at Barbados he was attacked by a bout of yellow fever, of which his wife died on 16 October and he on 19 October, having been delirious for several days, aged 58.[48][10][49][41] Grinfield was replaced as Commander-in-Chief by Major-General Sir Charles Green who went on with Hood to capture Suriname in 1804.[50][51] Grinfield left almost everything in his will to his younger brother Thomas (died 1824), a clergyman in Bristol.[Note 6][53][54]

Notes and citations

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ In this period officers of the Foot Guards held two ranks. Buying a commission in these regiments cost more than it would have in other regiments, and so if an officer in the Foot Guards transferred in his rank to a different regiment he would lose money. To counter this Foot Guards officers held both a regimental rank and an army rank; if they transferred to a regiment outside of the Foot Guards then they would hold their higher, army, rank and would therefore not lose money.[6]

- ^ Grinfield's full title was "Commander of all his Majesty's Land Forces serving in the Leeward and Windward Charibbee Islands, and in the Island of Trinidad".[26]

- ^ Tobago was officially ceded to Britain in 1814.[36]

- ^ Control of the British islands in the West Indies was wholly in the hands of civilian powers, and Grinfield's purview was limited only to protection of those islands.[38]

- ^ Along with the two islands, the Dutch 18-gun corvette Hippomenes was also taken.[43]

- ^ Grinfield had another brother, Steddy, a barrister and fellow of the Royal Society, who died in 1808.[52]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ward (1988), p. 68.

- ^ Hasler, P. W. "Marlborough, borough". The History of Parliament. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ^ Brown (2023), p. 93.

- ^ "No. 10039". The London Gazette. 27–30 September 1760. p. 1.

- ^ Monthly Visitor (1804), p. 304.

- ^ "Formation and role of the Regiments". The Guards Museum. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ a b c Cannon (1842), p. 66.

- ^ a b c Mackinnon (1833), p. 27.

- ^ Cannon (1842), pp. 66–67.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Cannon (1842), p. 67.

- ^ "London". The Bath Chronicle. Bath. 31 October 1793. p. 3.

- ^ Norton, Rictor. "General Gustavus Guydickens". Homosexuality in Eighteenth-Century England. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ Urban (1804), p. 179.

- ^ a b c d e f Ward (1988), p. 69.

- ^ Historical Manuscripts Commission (1894), p. 349.

- ^ Fryer (1989), p. 167.

- ^ "London". Hampshire Chronicle. Hampshire. 30 December 1797.

- ^ "Norwich, Dec. 12". Norfolk Chronicle. Norfolk. 12 December 1795.

- ^ War Office (1799), p. 6.

- ^ Cannon (1842), p. 12.

- ^ War Office (1799), p. 13.

- ^ House of Commons (1803), p. 689.

- ^ Temple-Nugent-Brydges-Chandos-Grenville (1855), p. 121.

- ^ Temple-Nugent-Brydges-Chandos-Grenville (1855), p. 133.

- ^ "Friday, January 9". Morning Post. London. 9 January 1801.

- ^ a b Cobbett (1802), p. 703.

- ^ Fortescue (1910), p. 181.

- ^ a b c Burns (1965), p. 582.

- ^ a b c d e f Fortescue (1910), p. 182.

- ^ a b c Howard (2015), p. 117.

- ^ a b Turner (1999), p. 26.

- ^ Calvert (1978), p. 138.

- ^ Southey (1827), pp. 230–231.

- ^ a b c Fortescue (1910), p. 183.

- ^ a b Howard (2015), p. 118.

- ^ a b Calvert (1978), p. 140.

- ^ Southey (1827), p. 230.

- ^ a b c d Fortescue (1910), p. 184.

- ^ a b Howard (2015), p. 119.

- ^ Fortescue (1910), p. 185.

- ^ a b c d e Fortescue (1910), p. 186.

- ^ Southey (1827), pp. 234–235.

- ^ a b Edinburgh Magazine (1803), p. 469.

- ^ Southey (1827), p. 235.

- ^ Edinburgh Magazine (1803), pp. 470–471.

- ^ "No. 15624". The London Gazette. 27 September 1803.

- ^ Monthly Visitor (1804), pp. 304–305.

- ^ a b Ward (1988), p. 70.

- ^ Edinburgh Magazine (1803), p. 470.

- ^ Fortescue (1910), p. 187.

- ^ Howard (2015), p. 120.

- ^ "Deaths". Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette. Bath. 10 November 1808.

- ^ Urban (1803), p. 1256.

- ^ Christian Remembrancer (1824), p. 184.

References

[edit]- Brown, Steve (2023). King George's Army: British Regiments and The Men Who Led Them 1793–1815. Vol. 1. Warwick: Helion. ISBN 978-1-804513-41-5.

- Burns, Alan Cuthbert (1965). History of the British West Indies. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- Calvert, Michael (1978). A Dictionary of Battles 1715–1815. London: New English Library. ISBN 9780450032264.

- Cannon, Richard (1842). Historical Record of the Eighty-Sixth, or the Royal County Down Regiment of Foot. London: J. W. Parker.

- Cobbett, William (1802). Cobbett's Annual Register. Vol. 1. London: Cox and Baylis.

- Fortescue, John (1910). A History of the British Army. Vol. 5. London: Macmillan and Co. OCLC 650331461.

- Fryer, Mary Beacock (1989). Elizabeth Posthuma Simcoe, 1762-1850 : A Biography. Toronto: Dundurn Press. ISBN 1550020641.

- Historical Manuscripts Commission (1894). The Manuscripts of J. B. Fortescue, Esq. Vol. 2. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

- House of Commons (1803). The Journals of the House of Commons. Vol. 53. London: House of Commons.

- Howard, Martin R. (2015). Death Before Glory! The British Soldier in the West Indies in the French Revolutionary & Napoleonic Wars. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-78159-341-7.

- Mackinnon, Daniel (1833). Origin and Services of the Coldstream Guards. Vol. 2. London: Richard Bentley.

- Southey, Thomas (1827). Chronological History of the West Indies. Vol. 3. London: Longman. OCLC 14936431.

- Temple-Nugent-Brydges-Chandos-Grenville, Richard Plantagenet (1855). Memoirs of the Court and Cabinets of George the Third. Vol. 3. London: Hurst and Blackett.

- The Christian Remembrancer. Vol. 6. London: C. & J. Rivington. 1824.

- The Edinburgh Magazine. Vol. December. Edinburgh: J. Ruthven and Sons. 1803.

- The Monthly Visitor. Vol. 6. London: J. Cundee. 1804.

- Turner, Wesley B. (1999). British Generals in the War of 1812. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-7735-1832-0.

- Urban, Sylvanus (1803). The Gentleman's Magazine. Vol. 73, Part 2. London: Nichols and Son.

- Urban, Sylvanus (1804). The Gentleman's Magazine. Vol. 74, Part 1. London: Nichols and Son.

- Ward, S. G. P. (Summer 1988). "Three Watercolour Portraits". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 66 (266): 63–71.

- War Office (1799). An Account of all the General and Staff Officers serving within Great Britain. London: War Office.