Xenon difluoride

2 crystals. 1962. | |

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC names

Xenon difluoride

Xenon(II) fluoride | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.033.850 |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| F2Xe | |

| Molar mass | 169.290 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | White solid |

| Density | 4.32 g/cm3, solid |

| Melting point | 128.6 °C (263.5 °F; 401.8 K)[2] |

| 25 g/L (0 °C) | |

| Vapor pressure | 6.0×102 Pa[1] |

| Structure | |

| parallel linear XeF2 units | |

| Linear | |

| 0 D | |

| Thermochemistry | |

Std molar

entropy (S⦵298) |

254 J·mol−1·K−1[3] |

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−108 kJ·mol−1[3] |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards

|

Corrosive to exposed tissues. Releases toxic compounds on contact with moisture.[5] |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H272, H301, H314, H330 | |

| P210, P220, P221, P260, P264, P270, P271, P280, P284, P301+P310+P330, P303+P361+P353, P304+P340+P310, P305+P351+P338, P331, P363, P370+P378, P403+P233, P405, P501[4] | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | PELCHEM MSDS |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions

|

Xenon dichloride Xenon dibromide |

Other cations

|

Krypton difluoride Radon difluoride |

Related compounds

|

Xenon tetrafluoride Xenon hexafluoride |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

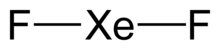

Xenon difluoride is a powerful fluorinating agent with the chemical formula XeF

2, and one of the most stable xenon compounds. Like most covalent inorganic fluorides it is moisture-sensitive. It decomposes on contact with water vapor, but is otherwise stable in storage. Xenon difluoride is a dense, colourless crystalline solid.

It has a nauseating odour and low vapor pressure.[6]

Structure

[edit]Xenon difluoride is a linear molecule with an Xe–F bond length of 197.73±0.15 pm in the vapor stage, and 200 pm in the solid phase. The packing arrangement in solid XeF

2 shows that the fluorine atoms of neighbouring molecules avoid the equatorial region of each XeF

2 molecule. This agrees with the prediction of VSEPR theory, which predicts that there are 3 pairs of non-bonding electrons around the equatorial region of the xenon atom.[1]

At high pressures, novel, non-molecular forms of xenon difluoride can be obtained. Under a pressure of ~50 GPa, XeF

2 transforms into a semiconductor consisting of XeF

4 units linked in a two-dimensional structure, like graphite. At even higher pressures, above 70 GPa, it becomes metallic, forming a three-dimensional structure containing XeF

8 units.[7] However, a recent theoretical study has cast doubt on these experimental results.[8]

The Xe–F bonds are weak. XeF2 has a total bond energy of 267.8 kJ/mol (64.0 kcal/mol), with first and second bond energies of 184.1 kJ/mol (44.0 kcal/mol) and 83.68 kJ/mol (20.00 kcal/mol), respectively. However, XeF2 is much more robust than KrF2, which has a total bond energy of only 92.05 kJ/mol (22.00 kcal/mol).[9]

Chemistry

[edit]Synthesis

[edit]Synthesis proceeds by the simple reaction:

- Xe + F2 → XeF2

The reaction needs heat, irradiation, or an electrical discharge. The product is a solid. It is purified by fractional distillation or selective condensation using a vacuum line.[10]

The first published report of XeF2 was in October 1962 by Chernick, et al.[11] However, though published later,[12] XeF2 was probably first created by Rudolf Hoppe at the University of Münster, Germany, in early 1962, by reacting fluorine and xenon gas mixtures in an electrical discharge.[13] Shortly after these reports, Weeks, Chernick, and Matheson of Argonne National Laboratory reported the synthesis of XeF2 using an all-nickel system with transparent alumina windows, in which equal parts xenon and fluorine gases react at low pressure upon irradiation by an ultraviolet source to give XeF2.[14] Williamson reported that the reaction works equally well at atmospheric pressure in a dry Pyrex glass bulb using sunlight as a source. It was noted that the synthesis worked even on cloudy days.[15]

In the previous syntheses the fluorine gas reactant had been purified to remove hydrogen fluoride. Šmalc and Lutar found that if this step is skipped the reaction rate proceeds at four times the original rate.[16]

In 1965, it was also synthesized by reacting xenon gas with dioxygen difluoride.[17]

Solubility

[edit]XeF

2 is soluble in solvents such as BrF

5, BrF

3, IF

5, anhydrous hydrogen fluoride, and acetonitrile, without reduction or oxidation. Solubility in hydrogen fluoride is high, at 167 g per 100 g HF at 29.95 °C.[1]

Derived xenon compounds

[edit]Other xenon compounds may be derived from xenon difluoride. The unstable organoxenon compound Xe(CF

3)

2 can be made by irradiating hexafluoroethane to generate CF•

3 radicals and passing the gas over XeF

2. The resulting waxy white solid decomposes completely within 4 hours at room temperature.[18]

The XeF+ cation is formed by combining xenon difluoride with a strong fluoride acceptor, such as an excess of liquid antimony pentafluoride (SbF

5):

- XeF

2 + SbF

5 → XeF+

+ SbF−

6

Adding xenon gas to this pale yellow solution at a pressure of 2–3 atmospheres produces a green solution containing the paramagnetic Xe+

2 ion,[19] which contains a Xe−Xe bond: ("apf" denotes solution in liquid SbF

5)

- 3 Xe(g) + XeF+

(apf) + SbF

5(l) ⇌ 2 Xe+

2(apf) + SbF−

6(apf)

This reaction is reversible; removing xenon gas from the solution causes the Xe+

2 ion to revert to xenon gas and XeF+

, and the color of the solution returns to a pale yellow.[20]

In the presence of liquid HF, dark green crystals can be precipitated from the green solution at −30 °C:

- Xe+

2(apf) + 4 SbF−

6(apf) → Xe+

2Sb

4F−

21(s) + 3 F−

(apf)

X-ray crystallography indicates that the Xe–Xe bond length in this compound is 309 pm, indicating a very weak bond.[18] The Xe+

2 ion is isoelectronic with the I−

2 ion, which is also dark green.[21][22]

Coordination chemistry

[edit]Bonding in the XeF2 molecule is adequately described by the three-center four-electron bond model.

XeF2 can act as a ligand in coordination complexes of metals.[1] For example, in HF solution:

- Mg(AsF6)2 + 4 XeF2 → [Mg(XeF2)4](AsF6)2

Crystallographic analysis shows that the magnesium atom is coordinated to 6 fluorine atoms. Four of the fluorine atoms are attributed to the four xenon difluoride ligands while the other two are a pair of cis-AsF−

6 ligands.[23]

A similar reaction is:

- Mg(AsF6)2 + 2 XeF2 → [Mg(XeF2)2](AsF6)2

In the crystal structure of this product the magnesium atom is octahedrally-coordinated and the XeF2 ligands are axial while the AsF−

6 ligands are equatorial.

Many such reactions with products of the form [Mx(XeF2)n](AF6)x have been observed, where M can be calcium, strontium, barium, lead, silver, lanthanum, or neodymium and A can be arsenic, antimony or phosphorus. Some of these compounds feature extraordinarily high coordination numbers at the metal center.[24]

In 2004, results of synthesis of a solvate where part of cationic centers were coordinated solely by XeF2 fluorine atoms were published.[25] Reaction can be written as:

- 2 Ca(AsF6)2 + 9 XeF2 → Ca2(XeF2)9(AsF6)4.

This reaction requires a large excess of xenon difluoride. The structure of the salt is such that half of the Ca2+ ions are coordinated by fluorine atoms from xenon difluoride, while the other Ca2+ ions are coordinated by both XeF2 and AsF−

6.

Applications

[edit]As a fluorinating agent

[edit]Xenon difluoride is a strong fluorinating and oxidizing agent.[26][27] With fluoride ion acceptors, it forms XeF+

and Xe

2F+

3 species which are even more powerful fluorinators.[1]

Among the fluorination reactions that xenon difluoride undergoes are:

- Oxidative fluorination:

- Ph3TeF + XeF2 → Ph3TeF3 + Xe

- Reductive fluorination:

- 2 CrO2F2 + XeF2 → 2 CrOF3 + Xe +O2

- Aromatic fluorination:

- Alkene fluorination:

- Radical fluorination in radical decarboxylative fluorination reactions,[10] in Hunsdiecker-type reactions where xenon difluoride is used to generate the radical intermediate as well as the fluorine transfer source,[28] and in generating aryl radicals from aryl silanes:[29]

XeF

2 is selective about which atom it fluorinates, making it a useful reagent for fluorinating heteroatoms without touching other substituents in organic compounds. For example, it fluorinates the arsenic atom in trimethylarsine, but leaves the methyl groups untouched:[30]

- (CH

3)

3As + XeF

2 → (CH

3)

3AsF

2 + Xe

XeF2 can similarly be used to prepare N-fluoroammonium salts, useful as fluorine transfer reagents in organic synthesis (e.g., Selectfluor), from the corresponding tertiary amine:[31]

- [R–(CH2CH2)3N:][BF−

4] + XeF2 + NaBF4 → [R–(CH2CH2)3–F][BF−

4]2 + NaF + Xe

XeF

2 will also oxidatively decarboxylate carboxylic acids to the corresponding fluoroalkanes:[32][33]

- RCOOH + XeF2 → RF + CO2 + Xe + HF

Silicon tetrafluoride has been found to act as a catalyst in fluorination by XeF

2.[34]

As an etchant

[edit]Xenon difluoride is also used as an isotropic gaseous etchant for silicon, particularly in the production of microelectromechanical systems (MEMS), as first demonstrated in 1995.[35] Commercial systems use pulse etching with an expansion chamber[36] Brazzle, Dokmeci, et al. describe this process:[37]

The mechanism of the etch is as follows. First, the XeF2 adsorbs and dissociates to xenon and fluorine atoms on the surface of silicon. Fluorine is the main etchant in the silicon etching process. The reaction describing the silicon with XeF2 is

- 2 XeF2 + Si → 2 Xe + SiF4

XeF2 has a relatively high etch rate and does not require ion bombardment or external energy sources in order to etch silicon.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Melita Tramšek; Boris Žemva (2006). "Synthesis, Properties and Chemistry of Xenon(II) Fluoride" (PDF). Acta Chim. Slov. 53 (2): 105–116. doi:10.1002/chin.200721209.

- ^ Hindermann, D. K., Falconer, W. E. (1969). "Magnetic Shielding of 19F in XeF2". J. Chem. Phys. 50 (3): 1203. Bibcode:1969JChPh..50.1203H. doi:10.1063/1.1671178.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Zumdahl, Steven S. (2009). Chemical Principles 6th Ed. Houghton Mifflin Company. p. A23. ISBN 978-0-618-94690-7.

- ^ "Sigma Aldrich Xenon Difluoride SDS". Sigma Aldrich. Millipore Sigma. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "MSDS: xenon difluoride" (PDF). BOC Gases. Retrieved 2010-06-01.

- ^ James L. Weeks; Max S. Matheson (1966). "Xenon Difluoride". Inorganic Syntheses. Vol. 8. pp. 260–264. doi:10.1002/9780470132395.ch69. ISBN 9780470132395.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Kim, M.; Debessai, M.; Yoo, C. S. (2010). "Two- and three-dimensional extended solids and metallization of compressed XeF2". Nature Chemistry. 2 (9): 784–788. Bibcode:2010NatCh...2..784K. doi:10.1038/nchem.724. PMID 20729901.

- ^ Kurzydłowski, D.; Zaleski-Ejgierd, P.; Grochala, W.; Hoffmann, R. (2011). "Freezing in Resonance Structures for Better Packing: XeF2Becomes (XeF+)(F−) at Large Compression". Inorganic Chemistry. 50 (8): 3832–3840. doi:10.1021/ic200371a. PMID 21438503.

- ^ Cockett, A. H.; Smith, K. C.; Bartlett, Neil (2013). The Chemistry of the Monatomic Gases. Pergamon Texts in Inorganic Chemistry. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Science. ISBN 9781483157368. OCLC 953379200.

- ^ a b Tius, M. A. (1995). "Xenon difluoride in synthesis". Tetrahedron. 51 (24): 6605–6634. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(95)00362-C.

- ^ Chernick, CL and Claassen, HH and Fields, PR and Hyman, HH and Malm, JG and Manning, WM and Matheson, MS and Quarterman, LA and Schreiner, F. and Selig, HH; et al. (1962). "Fluorine Compounds of Xenon and Radon". Science. 138 (3537): 136–138. Bibcode:1962Sci...138..136C. doi:10.1126/science.138.3537.136. PMID 17818399. S2CID 10330125.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hoppe, R.; Daehne, W.; Mattauch, H.; Roedder, K. (1962). "Fluorination of Xenon". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1 (11): 599. doi:10.1002/anie.196205992.

- ^ Hoppe, R. (1964). "Die Valenzverbindungen der Edelgase". Angewandte Chemie. 76 (11): 455. Bibcode:1964AngCh..76..455H. doi:10.1002/ange.19640761103. First review on the subject by the pioneer of covalent noble gas compounds.

- ^ Weeks, J.; Matheson, M.; Chernick, C. (1962). "Photochemical Preparation of Xenon Difluoride" Photochemical Preparation of Xenon Difluoride". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 84 (23): 4612–4613. doi:10.1021/ja00882a063.

- ^ Williamson, Stanley M.; Sladky, Friedrich O.; Bartlett, Neil (1968). "Xenon Difluoride". Inorganic Syntheses. Vol. 11. pp. 147–151. doi:10.1002/9780470132425.ch31. ISBN 9780470132425.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Šmalc, Andrej; Lutar, Karel; Kinkead, Scott A. (2007). "Xenon Difluoride (Modification)". Inorganic Syntheses. Vol. 29. pp. 1–4. doi:10.1002/9780470132609.ch1. ISBN 9780470132609.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Morrow, S. I.; Young, A. R. (1965). "The Reaction of Xenon with Dioxygen Difluoride. A New Method for the Synthesis of Xenon Difluoride". Inorganic Chemistry. 4 (5): 759–760. doi:10.1021/ic50027a038.

- ^ a b Harding, Charlie; Johnson, David Arthur; Janes, Rob (2002). Elements of the p block. Royal Society of Chemistry, Open University. ISBN 978-0-85404-690-4.

- ^ Brown, D. R.; Clegg, M. J.; Downs, A. J.; Fowler, R. C.; Minihan, A. R.; Norris, J. R.; Stein, L. . (1992). "The dixenon(1+) cation: formation in the condensed phases and characterization by ESR, UV-visible, and Raman spectroscopy". Inorganic Chemistry. 31 (24): 5041–5052. doi:10.1021/ic00050a023.

- ^ Stein, L.; Henderson, W. W. (1980). "Production of dixenon cation by reversible oxidation of xenon". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 102 (8): 2856–2857. Bibcode:1980JAChS.102.2856S. doi:10.1021/ja00528a065.

- ^ Mackay, Kenneth Malcolm; Mackay, Rosemary Ann; Henderson, W. (2002). Introduction to modern inorganic chemistry (6th ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-7487-6420-4.

- ^ Egon Wiberg; Nils Wiberg; Arnold Frederick Holleman (2001). Inorganic chemistry. Academic Press. p. 422. ISBN 978-0-12-352651-9.

- ^ Tramšek, M.; Benkič, P.; Žemva, B. (2004). "First Compounds of Magnesium with XeF2". Inorg. Chem. 43 (2): 699–703. doi:10.1021/ic034826o. PMID 14731032.

- ^ Grochala, Wojciech (Oct 2007) [12 April 2007]. "Atypical compounds of gases, which have been called 'noble'". Chemical Society Reviews. 36 (10). Royal Society of Chemistry: 1640. doi:10.1039/b702109g. PMID 17721587 – via CiteSeerX.

- ^ Tramšek, M.; Benkič, P.; Žemva, B. (2004). "The First Compound Containing a Metal Center in a Homoleptic Environment of XeF2 Molecules". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 43 (26): 3456–8. doi:10.1002/anie.200453802. PMID 15221838.

- ^ Halpem, D. F. (2004). "Xenon(II) Fluoride". In Paquette, L. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. New York, NY: J. Wiley & Sons.

- ^ Taylor, S.; Kotoris, C.; Hum, G. (1999). "Recent Advances in Electrophilic Fluorination". Tetrahedron. 55 (43): 12431–12477. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(99)00748-6.

- ^ Patrick, T. B.; Darling, D. L. (1986). "Fluorination of activated aromatic systems with cesium fluoroxysulfate". J. Org. Chem. 51 (16): 3242–3244. doi:10.1021/jo00366a044.

- ^ Lothian, A. P.; Ramsden, C. A. (1993). "Rapid fluorodesilylation of aryltrimethylsilanes using xenon difuoride: An efficient new route to aromatic fluorides". Synlett. 1993 (10): 753–755. doi:10.1055/s-1993-22596. S2CID 196734038.

- ^ W. Henderson (2000). Main group chemistry. Great Britain: Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-85404-617-1.

- ^ Shunatona, Hunter P.; Früh, Natalja; Wang, Yi-Ming; Rauniyar, Vivek; Toste, F. Dean (2013-07-22). "Enantioselective Fluoroamination: 1,4-Addition to Conjugated Dienes Using Anionic Phase-Transfer Catalysis". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 52 (30): 7724–7727. doi:10.1002/anie.201302002. ISSN 1521-3773. PMID 23766145.

- ^ Patrick, Timothy B.; Johri, Kamalesh K.; White, David H.; Bertrand, William S.; Mokhtar, Rodziah; Kilbourn, Michael R.; Welch, Michael J. (1986). "Replacement of the carboxylic acid function with fluorine". Can. J. Chem. 64: 138–141. doi:10.1139/v86-024.

- ^ Grakauskas, Vytautas (1969). "Aqueous fluorination of carboxylic acid salts". J. Org. Chem. 34 (8): 2446–2450. doi:10.1021/jo01260a040.

- ^ Tamura Masanori; Takagi Toshiyuki; Shibakami Motonari; Quan Heng-Dao; Sekiya Akira (1998). "Fluorination of olefins with xenon difluoride-silicon tetrafluoride". Fusso Kagaku Toronkai Koen Yoshishu (in Japanese). 22: 62–63. Journal code: F0135B; accession code: 99A0711841.

- ^ Chang, F.; Yeh, R.; G., Lin; Chu, P.; Hoffman, E.; Kruglick, E.; Pister, K.; Hecht, M. (1995). "Gas-phase silicon micromachining with xenon difluoride". In Bailey, Wayne; Motamedi, M. Edward; Luo, Fang-Chen (eds.). Microelectronic Structures and Microelectromechanical Devices for Optical Processing and Multimedia Applications. Vol. 2641. pp. 117–128. Bibcode:1995SPIE.2641..117C. doi:10.1117/12.220933. S2CID 39522253.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Chu, P.; Chen, J.; Chu, P.; Lin, G.; Huang, J.; Warneke, B; Pister, K. (1997). Controlled Pulse-Etching with Xenon Difluoride. Int. Conf. Solid State Sensors and Actuators (Transducers 97). pp. 665–668.

- ^ Brazzle, J. D.; Dokmeci, M. R.; Mastrangelo, C. H. (2004). "Modeling and characterization of sacrificial polysilicon etching using vapor-phase xenon difluoride". 17th IEEE International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems. Maastricht MEMS 2004 Technical Digest. 17th IEEE International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS). pp. 737–740. doi:10.1109/MEMS.2004.1290690. ISBN 0-7803-8265-X.

Further reading

[edit]- Greenwood, Norman Neill; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 894. ISBN 978-0-7506-3365-9.