George Scot of Pitlochie

George Scot | |

|---|---|

Dunnottar Castle by John Slezer (1693) | |

| Born | c. 1640 Pitlochie, Fife |

| Died | 1685 (aged 44–45) the Atlantic Ocean |

| Occupation | Colonist |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Spouse |

Margaret Rigg (m. 1663) |

| Parents | John Scot of Scotstarvet Elizabeth Melville |

George Scot or Scott (c. 1640 – 1685) of Pitlochie, Fife was a Scottish writer on colonisation in North America.

Early life[edit]

Scot, who was born around 1640, was the only son of John Scot of Scotstarvet by his second wife, Elizabeth Melville, daughter of Sir James Melville, 2nd of Halhill.[2][3]

Career[edit]

In 1685, Scot published at Edinburgh The Model of the Government of the Province of East New Jersey, in America; and Encouragement for such as design to be concerned there. It was, says the author, the outcome of a visit to London in 1679, when he met "several substantial and judicious gentlemen concerned in the American plantations". Among them were James Drummond, 4th Earl of Perth, to whom the book is dedicated, and probably William Penn. The work included a series of letters from the early settlers in New Jersey.[2]

The Model was plagiarised by Samuel Smith (1720–1776) in his History of New Jersey (1765), and is quoted by George Bancroft; James Grahame (1790–1842) author of the Rise and Progress of the United States, emphasised it. It was reprinted for the New Jersey Historical Society in 1846, in William Adee Whitehead's East Jersey under the Proprietary Governments (2nd edition 1875). In some copies a passage (p. 37) recommending religious freedom as an inducement to emigration is modified.[2]

Imprisonment and colonisation[edit]

In 1674, Scot was fined and imprisoned as a Covenanter.[4] In 1676, further charges were laid against Scot and his wife; and in 1677, having failed to appear when summoned by the Scottish council, he was declared a fugitive. He was arrested in Edinburgh. Imprisoned on Bass Rock, he was released later in the year on bond.[5]

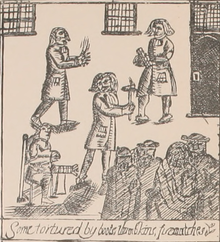

In 1679, Scot was questioned about John Balfour of Kinloch, involved in the murder of James Sharp.[6][7] He spent time in London, where he made contact with Scots planning colonial projects; and was imprisoned again. Released in 1684, he put together a colonisation scheme, involving the preacher Archibald Riddell who was his wife's cousin, and went willingly being at the time imprisoned on the Bass Rock. Lacking other support, a group of Covenanters being held prisoner in Dunnottar Castle and other prisoners of conscience from the jails of Edinburgh were given to Scot, many of whom were likely taken against their will to the plantations.[5] Several of the prisoners were tortured because they had tried to escape.[1] One of the prisoners was John Fraser who was captured with Alexander Shields at a conventicle in London.[8] About 40 of the prisoners had their ears cut and women who had disowned the king were branded on the shoulder so they might be recognised and hung if they returned.[9]

In recognition of his services as a writer, Scot received from the proprietors of East New Jersey a grant, dated 28 July 1685, of five hundred acres of land in the province.[2] On 1 August 1685, Scot embarked in the Henry and Francis with nearly two hundred others, including his wife and family; but he and his wife died on the voyage.[2][10] The individuals transported to America by George Scot had been purchased and were severely mistreated, according to Robert Wodrow.[11]

Personal life[edit]

In 1663, Scot was married to Margaret Rigg, daughter of William Rigg of Aithernie.[5] A son and a daughter survived the Atlantic voyage, including:

- Euphame Scot, who married John Johnstone (c. 1661–1732), an Edinburgh druggist, in 1686. Johnston had been one of her fellow-passengers on the voyage to New Jersey. He later served as mayor of New York City.[12] To him the proprietors issued, on 13 January 1687, a confirmation of the grant made to Scot.[2]

- William Scot, born 7 February 1666.[13]

- Katherine Scot, baptized at Abbotshall on 20 August 1669

Descendants[edit]

Scot's descendants occupied a position in the colony until the American Revolution, including grandson Andrew Johnston, Speaker of the New Jersey General Assembly, and great-grandson David Johnston, a merchant and member of the New York General Assembly. At that point most left as Loyalists, but some remained.[2]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Erskine, John; Macleod, Walter (1893). Journal of the Hon. John Erskine of Carnock, 1683-1687. Edinburgh: Printed at University press by T. and A. Constable for the Scottish history society. p. 154. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ^ Reg. Mag. Sig. 11: 462-463 states the mother of George Scot is Elizabeth Melville: 1666 Jul 6 - Margaret Rig, daughter of the deceased William Rig of Athernie, now the wife of Mr. George Scot, son of Sir John Scot of Scotstarvet, knight, by the deceased Dame Elizabeth Melvill, his wife

- ^ M'Crie, Thomas, D.D. the younger (1847). The Bass rock: Its civil and ecclesiastic history. Edinburgh: J. Greig & Son. pp. 157–173. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Handley, Stuart. "Scot, George, of Scotstarvit". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/24868. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Laing, David (1848). Historical Notices of Scotish Affairs: Selected from the Manuscripts of Sir John Lauder of Fountainhall. Vol. 1. Edinburgh: T. Constable, printer to Her Majesty. pp. 226, 408. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ Jardine, Mark (21 June 2018). "The Torn Bible of the Covenanter and Assassin Balfour at RUSI". Jardine's Book of Martyrs. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ^ Laing, David (1848). Historical Notices of Scotish Affairs: Selected from the Manuscripts of Sir John Lauder of Fountainhall. Vol. 2. Edinburgh: T. Constable, printer to Her Majesty. p. 627. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- ^ Laing, David (1848). Historical Notices of Scotish Affairs: Selected from the Manuscripts of Sir John Lauder of Fountainhall. Vol. 2. Edinburgh: T. Constable, printer to Her Majesty. p. 658. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- ^ Tate, Sheila. "Henry & Francis of New Castle". Immigrant Ships Transcribers Guild. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ Wodrow, Robert (1835). The history of the sufferings of the Church of Scotland from the restoration to the revolution. Vol. 4. Glasgow: Blackie & Son. pp. 332–334. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- ^ Mather, Edith, H (1922). Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society. Vol. 7. Edison, N.J., etc., New Jersey Historical Society, etc. pp. 260–278. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ MacGregor, Gordon (2019). Red Book of Scotland, Volume VIII. Scotland. pp. 630, 631. ISBN 978-0-9545628-6-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- Attribution

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Scott, George (d.1685)". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Scott, George (d.1685)". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.