Germaine de Staël

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2023) |

}}

Germaine de Staël | |

|---|---|

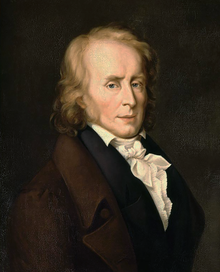

"Madame de Staël" (1813) | |

| Born | Anne-Louise Germaine Necker 22 April 1766 Paris, France |

| Died | 14 July 1817 (aged 51) Paris, France |

| Notable work |

|

| Spouses | |

| Parents | |

| School | Romanticism |

Main interests | |

| Signature | |

Anne Louise Germaine de Staël-Holstein (French: [an lwiz ʒɛʁmɛn də stal ɔlstajn]; née Necker; 22 April 1766 – 14 July 1817), commonly known as Madame de Staël (French: [madam də stal]), was a prominent philosopher, woman of letters, and political theorist in both Parisian and Genevan intellectual circles. She was the daughter of banker and French finance minister Jacques Necker and Suzanne Curchod, a respected salonhostess. Throughout her life, she held a moderate stance during the tumultuous periods of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic era, persisting until the time of the French Restoration.[3]

Her presence at critical events such as the Estates General of 1789 and the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen underscored her engagement in the political discourse of her time.[4] However, Madame de Staël faced exile for extended periods: initially during the Reign of Terror and subsequently due to personal persecution by Napoleon. She claimed to have discerned the tyrannical nature and ambitions of his rule ahead of many others.[5][6][non-primary source needed]

During her exile, she fostered the Coppet group, a network that spanned across Europe, positioning herself at its heart. Her literary works, emphasizing individuality and passion, left an enduring imprint on European intellectual thought. De Staël's repeated championing of Romanticism contributed significantly to its widespread recognition.[6]

While her literary legacy has somewhat faded with time, her critical and historical contributions hold undeniable significance. Though her novels and plays may now be less remembered, the value of her analytical and historical writings remains steadfast.[7] Within her work, de Staël not only advocates for the necessity of public expression but also sounds cautionary notes about its potential hazards.[8]

Childhood[edit]

Germaine (or Minette) was the only child of the Swiss governess Suzanne Curchod, who had an aptitude for mathematics and science, and prominent Swiss German banker and statesman Jacques Necker. Jacques was the son of Prof. Dr. jur. Karl Friedrich Necker from Brandenburg (Holy Roman Empire). He became the Director-General of Finance under King Louis XVI of France and she hosted in Rue de la Chaussée-d'Antin one of the most popular salons of Paris.[9] Mme Necker wanted her daughter educated according to the principles of the Swiss philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau and endow her with the intellectual education and Calvinist discipline instilled in her by her father.[10] On Fridays she regularly brought Germaine as a young child to sit at her feet in her salon, where the guests took pleasure in stimulating the brilliant child. Celebrities such as the Comte de Buffon, Jean-François Marmontel, Melchior Grimm, Edward Gibbon, the Abbé Raynal, Jean-François de la Harpe, Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, Denis Diderot, and Jean d'Alembert were frequent visitors.[11] At the age of 13, she read Montesquieu, Shakespeare, Rousseau and Dante.[12] Her parents' social life led to a somewhat neglected and wild Germaine, unwilling to bow to her mother's demands.

Her father "is remembered today for taking the unprecedented step in 1781 of making public the country's budget, a novelty in an absolute monarchy where the state of the national finances had always been kept secret, leading to his dismissal by the King in May of that year."[13] The family eventually took up residence in 1784 at Château Coppet, an estate on Lake Geneva. The family returned to the Paris region in 1785.[9]

Marriage[edit]

Aged 11, Germaine had suggested to her mother that she marry Edward Gibbon, a visitor to her salon, whom she found most attractive. Then, she reasoned, he would always be around for her.[14] In 1783, at seventeen, she was courted by William Pitt the Younger and by Comte de Guibert, whose conversation, she thought, was the most far-ranging, spirited and fertile she had ever known.[15] When she did not accept their offers Germaine's parents became impatient. With the help of Marie-Charlotte Hippolyte de Boufflers, a marriage was arranged with Baron Erik Magnus Staël von Holstein, a Protestant and attaché of the Swedish legation to France. The wedding took place on 14 January 1786 in the Swedish embassy at 97, Rue du Bac; Germaine was 19, and her husband 37.[16] On the whole, the marriage seems to have been workable for both parties, although neither seems to have had much affection for the other. Madame de Staël continued to write miscellaneous works, including the three-act romantic drama Sophie (1786) and the five-act tragedy, Jeanne Grey (1787). The baron, also a gambler, obtained great benefits from the match as he received 80,000 pounds and was confirmed as lifetime ambassador to Paris.[17]

Revolutionary activities[edit]

In 1788, de Staël published Letters on the works and character of J.J. Rousseau.[18] De Staël was at this time enthusiastic about the mixture of Rousseau's ideas about love and Montesquieu's on politics.[19]

In December 1788 her father persuaded Louis XVI to double the number of deputies at the Third Estate in order to gain enough support to raise taxes to pay for the excessive costs of supporting the revolutionaries in America. This approach had serious repercussions on Necker's reputation; he appeared to consider the Estates-General as a facility designed to help the administration rather than to reform the government.[20] In an argument with the king, whose speech on 23 June he didn't attend, Necker was dismissed and exiled on 11 July. Her parents left France on the same day in unpopularity and disgrace. On Sunday, 12 July the news became public, and an angry Camille Desmoulins suggested storming the Bastille.[21] On 16 July he was reappointed; Necker entered Versailles in triumph. His efforts to clean up public finances were unsuccessful and his idea of a National Bank failed. Necker was attacked by Jean-Paul Marat and Count Mirabeau in the Constituante, when he did not agree with using assignats as legal tender.[22] He resigned on 4 September 1790. Accompanied by their son-in-law, her parents left for Switzerland, without the two million livres, half of his fortune, loaned as an investment in the public treasury in 1778.[23][24][25]

The increasing disturbances caused by the Revolution made her privileges as the consort of an ambassador an important safeguard. Germaine held a salon in the Swedish embassy, where she gave "coalition dinners", which were frequented by moderates such as Talleyrand and De Narbonne, monarchists (Feuillants) such as Antoine Barnave, Charles Lameth and his brothers Alexandre and Théodore, the Comte de Clermont-Tonnerre, Pierre Victor, baron Malouet, the poet Abbé Delille, Thomas Jefferson, the one-legged Minister Plenipotentiary to France Gouverneur Morris, Paul Barras (from the Plain) and the Girondin Condorcets.[citation needed]

During this time of her political thoughts, de Staël was focused on the problem of leadership, or the perceived lack of it. In her later works she often returned to the idea that "the French Revolution has been characterized by a surprising absence of eminent personalities".[26] She experienced the death of Mirabeau, accused of royalism, as a sign of great political disorientation and uncertainty.[citation needed]

Following the 1791 French legislative election, and after the French Constitution of 1791 was announced in the National Assembly, she resigned from a political career and decided not to stand for re-election. "Fine arts and letters will occupy my leisure."[27] She did, however, play an important role in the succession of Comte de Montmorin the Minister of Foreign Affairs, and in the appointment of Narbonne as minister of War and continued to be centre stage behind the scenes.[28] Marie Antoinette wrote to Hans Axel Fersen: "Count Louis de Narbonne is finally Minister of War, since yesterday; what a glory for Mme de Staël and what a joy for her to have the whole army, all to herself."[29] In 1792 the French Legislative Assembly saw an unprecedented turnover of ministers, six ministers of the interior, seven ministers of foreign affairs, and nine ministers of war.[30] On 10 August 1792 Clermont-Tonnere was thrown out of a window of the Louvre Palace and trampled to death. De Staël offered baron Malouet a plan of escape for the royal family to Dieppe.[31] On 20 August De Narbonne arrived in England on a German passport. As there was no government, militant members of the Insurrectionary Commune were given extensive police powers from the provisional, executive council, " to detain, interrogate and incarcerate suspects without anything resembling due process of law".[32] She helped De Narbonne, dismissed for plotting, to hide under the altar in the chapel in the Swedish embassy, and lectured the sans-culottes from the section in the hall.[33][34][35][12]

On Sunday 2 September, the day the Elections for the National Convention and the September massacres began, she fled herself in the garb of an ambassadress. Her carriage was stopped and the crowd forced her into the Paris town hall, where Robespierre presided.[36] That same evening she was conveyed home, escorted by the procurator Louis Pierre Manuel. The next day the commissioner to the Commune of Paris Jean-Lambert Tallien arrived with a new passport and accompanied her to the edge of the barricade.[37][38]

Salons at Coppet and Paris[edit]

After her flight from Paris, de Staël moved to Rolle in Switzerland, where Albert was born. She was supported by de Montmorency and the Marquis de Jaucourt, whom she had previously supplied with Swedish passports.[39] In January 1793, she made a four-month visit to England to be with her then-lover, the Comte de Narbonne, at Juniper Hall. (Since 1 February, France and Great Britain had been at war.) Within a few weeks, she was pregnant; it was apparently one of the reasons for the scandal she caused in England. According to Fanny Burney, the result was that her father urged Fanny to avoid the company of de Staël and her circle of French Émigrés in Surrey.[4] De Staël met Horace Walpole, James Mackintosh, Lord Sheffield, a friend of Edward Gibbon, and Lord Loughborough, the new Lord Chancellor.[4] She was not impressed with the condition of women in English society, finding that they were not afforded the voice and respect they deserved.[40][4] Staël viewed freedom as twofold: political freedom from institutions and individual freedom from social norms.[41][42]

In the summer of 1793, de Staël returned to Switzerland, probably because De Narbonne had cooled towards her. She published a defence of the character of Marie Antoinette, entitled, Réflexions sur le procès de la Reine, 1793 ("Reflections on the Queen's trial"). In de Staël's view, France should have adapted from an absolute to a constitutional monarchy as was the case in England.[43] Living in Jouxtens-Mézery, farther away from the French border than Coppet, Germaine was visited by Adolph Ribbing.[12][39] Count Ribbing was living in exile, after his conviction for taking part in a conspiracy to assassinate the Swedish king, Gustav III. In September 1794, the recently divorced Benjamin Constant visited her, wanting to meet her before he committed suicide.

In May 1795, de Staël moved to Paris, now with Constant in tow, as her protégé and lover.[44] De Staël rejected the idea of the right of resistance – which had been introduced into the never implemented French Constitution of 1793, and was removed from the Constitution of 1795.[45] In 1796, she published Sur l'influence des passions, in which she praised suicide and discussed how passions affect the happiness of individuals and societies, a book which attracted the attention of the German writers Schiller and Goethe.[46][47]

"Passionate love is natural to human beings and to yield oneself to love will not result in abandoning virtue".[48]

Still absorbed by French politics, de Staël reopened her salon.[49] It was during these years that Mme de Staël arguably exerted most political influence. For a time she was still visible in the diverse and eccentric society of the mid-1790s. However, on the 13 Vendémiaire the Comité de salut public ordered her to leave Paris after accusations of politicking, and put Constant in detention for one night.[50] De Staël spent that autumn in the spa of Forges-les-Eaux. She was considered a threat to political stability and mistrusted by both sides in the political conflict.[51] She corresponded with Franciso de Miranda whom she wished to see again.[52] The couple moved to Ormesson-sur-Marne where they stayed with Mathieu Montmorency. In Summer 1796 Constant founded the "Cercle constitutionnel" in Luzarches with de Staël's support.[53] In May 1797, she was back in Paris and eight months pregnant. She organized the Club du Salm in Hôtel de Salm.[54] De Stael succeeded in getting Talleyrand from the list of Émigrés and on his return from the United States to have him appointed Minister of Foreign Affairs in July.[55] From the coup of 18 Fructidor it was announced that anyone campaigning to restore the monarchy or the French Constitution of 1793 would be shot without trial.[56] Germaine moved to Saint-Ouen, on her father's estate and became a close friend of the beautiful and wealthy Juliette Récamier to whom she sold her parents' house in the Rue de la Chaussée-d'Antin.

De Staël completed the initial part of her first most substantial contribution to political and constitutional theory, "Of present circumstances that can end the Revolution, and of the principles that must found the republic of France".[13]

Conflict with Napoleon[edit]

On 6 December 1797 de Staël had the first meeting with Napoleon Bonaparte in Talleyrand's office and met him again on 3 January 1798 during a ball. She made it clear to him that she did not agree with his planned invasion of Switzerland. He ignored her opinions and would not read her letters.[57] In January 1800, Napoleon appointed Benjamin Constant a member of the Tribunat; not long after, Constant became his enemy. Two years later, Napoleon forced him into exile on account of his speeches which he took to be actually written by Mme de Staël.[48] In August 1802, Napoleon was elected first consul for life. This put de Staël into opposition to him both for personal and political reasons. In her view, Napoleon had begun to resemble Machiavelli's princes in The Prince (in fact tyrants); while for Napoleon, Voltaire, J.J. Rousseau and their followers were the cause of the French Revolution.[58] This view was cemented when Jacques Necker published his "Last Views on Politics and Finance" and his daughter, her "De la littérature considérée dans ses rapports avec les institutions sociales". It was her first philosophical treatment of the Europe question: it dealt with such factors as nationality, history, and social institutions.[59] Napoleon started a campaign against her latest publication. He did not like her cultural determinism and generalizations, in which she stated that "an artist must be of his own time".[48][60] In his opinion a woman should stick to knitting.[61] He said about her, according to the Memoirs of Madame de Rémusat, that she "teaches people to think who had never thought before, or who had forgotten how to think".[62] It became clear that the first man of France and de Staël were not likely ever to get along together.[63]

"It seems to me that life's circumstances, being ephemeral, teach us less about durable truths than the fictions based on those truths; and that the best lessons of delicacy and self-respect are to be found in novels where the feelings are so naturally portrayed that you fancy you are witnessing real life as you read."[64]

De Staël published a provocative, anti-Catholic novel Delphine, in which the femme incomprise (misunderstood woman) living in Paris between 1789 and 1792, is confronted with conservative ideas about divorce after the Concordat of 1801. In this tragic novel, influenced by Goethe's The Sorrows of Young Werther and Rousseau's Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse, she reflects on the legal and practical aspects on divorce, the arrests and the September Massacres, and the fate of the émigrés. (During the winter of 1794 it seems De Staël was pondering a divorce and whether to marry Ribbing.) The main characters have traits of the unstable Benjamin Constant, and Talleyrand is depicted as an old woman, herself as the heroine with the liberal view of the Italian aristocrat and politician Melzi d'Eril.[65]

When Constant moved to Maffliers in September 1803 de Staël went to see him and let Napoleon know she would be wise and cautious. Thereupon her house immediately became popular again among her friends, but Napoleon, informed by Madame de Genlis, suspected a conspiracy. "Her extensive network of connections – which included foreign diplomats and known political opponents, as well as members of the government and of Bonaparte's own family – was in itself a source of suspicion and alarm for the government."[66] Her protection of Jean Gabriel Peltier – who plotted the death of Napoleon – influenced his decision on 13 October 1803 to exile her without trial.[67]

Years of exile[edit]

For ten years, de Staël was not allowed to come within 40 leagues (almost 200 km) of Paris. She accused Napoleon of "persecuting a woman and her children".[68] On 23 October, she left for Germany "out of pride", in the hope of gaining support and to be able to return home as soon as possible.[69][70]

German travels[edit]

With her children and Constant, de Staël stopped off in Metz and met Kant's French translator Charles de Villers. In mid-December, they arrived in Weimar, where she stayed for two and a half months at the court of the Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach and his mother Anna Amalia. Goethe who had become ill hesitated about seeing her. After meeting her, Goethe went on to refer to her as an "extraordinary woman" in his private correspondence.[71] Schiller complimented her intelligence and eloquence, but her frequent visits distracted him from completing William Tell.[72][73] De Staël was constantly on the move, talking and asking questions.[74][48] Constant decided to abandon her in Leipzig and return to Switzerland. De Staël travelled on to Berlin, where she made the acquaintance of August Schlegel who was lecturing there on literature. She appointed him on an enormous salary to tutor her children. On 18 April they all left Berlin when the news of her father's death reached her.

Mistress of Coppet[edit]

On 19 May, de Staël arrived in Coppet now its wealthy and independent mistress. She spent the summer at the chateau sorting through his writings and published an essay on his private life. In April 1804, Friedrich Schlegel married Dorothea Veit in the Swedish embassy. In July Constant wrote about de Staël, "She exerts over everything around her a kind of inexplicable but real power. If only she could govern herself, she might have governed the world."[75] In December 1804 she travelled to Italy, accompanied by her children, August Wilhelm Schlegel, and the historian Sismondi. There she met the poet Monti and the painter, Angelica Kauffman. "Her visit to Italy helped her to develop her theory of the difference between northern and southern societies..."[4]

De Staël returned to Coppet in June 1805, moved to Meulan (Château d'Acosta), and spent nearly a year writing her next book on Italy's culture and history. In Corinne ou l'Italie (1807), her own impressions of a sentimental and intellectual journey, the heroine appears to have been inspired by the Italian poet Diodata Saluzzo Roero.[76][77] The book tells the story of two lovers: Corinne, the Italian poet, and Lord Nelvil, the English noble, traveling through Italy on a journey in part mirroring Staël’s own travels. (Staël appears to have identified with her character, and there are several portraits of Staël represented as Corinne.)[78] She combined romance with travelogue, showed all of Italy's works of art still in place, rather than plundered by Napoleon and taken to France.[79] The book's publication acted as a reminder of her existence, and Napoleon sent her back to Coppet. Her house became, according to Stendhal, "the general headquarters of European thought" and was a debating club hostile to Napoleon, "turning conquered Europe into a parody of a feudal empire, with his own relatives in the roles of vassal states".[80] Madame Récamier, also banned by Napoleon, Prince Augustus of Prussia, Charles Victor de Bonstetten, and Chateaubriand all belonged to the "Coppet group".[81][82] Each day the table was laid for about thirty guests. Talking seemed to be everybody's chief activity.

For a time de Staël lived with Constant in Auxerre (1806), Rouen (1807), Aubergenville (1807). Then she met Friedrich Schlegel, whose wife Dorothea had translated Corinne into German.[83] The use of the word Romanticism was invented by Schlegel but spread more widely across France through its persistent use by de Staël.[84] Late in 1807 she set out for Vienna and visited Maurice O'Donnell.[85] She was accompanied by her children and August Schlegel who gave his famous lectures there. In 1808 Benjamin Constant was afraid to admit to her that he had married Charlotte von Hardenberg in the meantime. "If men had the qualities of women", de Staël wrote, "love would simply cease to be a problem."[86] De Staël set to work on her book about Germany – in which she presented the idea of a state called "Germany" as a model of ethics and aesthetics and praised German literature and philosophy.[87] The exchange of ideas and literary and philosophical conversations with Goethe, Schiller, and Wieland had inspired de Staël to write one of the most influential books of the nineteenth century on Germany.[88]

Return to France[edit]

Pretending she wanted to emigrate to the United States, de Staël was given permission to re-enter France. She moved first into the Château de Chaumont (1810), then relocated to Fossé and Vendôme. She was determined to publish De l'Allemagne in France, a multi-volume book about German culture and in particular the growing movement of German Romanticism. The book was considered "dangerous" by Napoleon as it favorably presented "new and foreign ideas" that challenged existing French political structures.[89] Constrained by censorship, she wrote to the emperor a letter of complaint.[90] The minister of police Savary had emphatically forbidden her to publish her "un-French" book.[88] In 1810, after de Staël had successfully published her book in France, Napoleon ordered the destruction of all 10,000 copies.[91] In October of the same year, she was exiled again and had to leave France within three days. August Schlegel was also ordered to leave the Swiss Confederation as an enemy of French literature. De Staël found consolation in a wounded veteran officer named Albert de Rocca, twenty-three years her junior, to whom she got privately engaged in 1811 but did not marry publicly until 1816.[48]

East European travels[edit]

The operations of the French imperial police in the case of de Staël are rather obscure. She was at first left undisturbed, but by degrees, the chateau itself became a source of suspicion, and her visitors found themselves heavily persecuted. François-Emmanuel Guignard, De Montmorency and Mme Récamier were exiled for the crime of visiting her. She remained at home during the winter of 1811, planning to escape to England or Sweden with the manuscript. On 23 May 1812, she left Coppet under the pretext of a short outing, but journeyed through Bern, Innsbruck and Salzburg to Vienna, where she met Metternich. There, after some trepidation and trouble, she received the necessary passports to go on to Russia.[92]

During Napoleon's invasion of Russia, de Staël, her two children, and Schlegel travelled through Galicia in the Habsburg empire from Brno to Łańcut where de Rocca, having deserted the French army and having been searched by the French gendarmerie, was waiting for her. The journey continued to Lemberg. On 14 July 1812 they arrived in Volhynia. In the meantime, Napoleon, who took a more northern route, had crossed the Niemen River with his army. In Kyiv, she met Miloradovich, governor of the city. De Staël hesitated to travel on to Odessa, Constantinople, and decided instead to go north. Perhaps she was informed of the outbreak of plague in the Ottoman Empire. In Moscow, she was invited by the governor Fyodor Rostopchin. According to de Staël, it was Rostopchin who ordered his mansion in Italian style near Winkovo to be set on fire.[93] She left only a few weeks before Napoleon arrived there. Until 7 September, her party stayed in Saint Petersburg. According to John Quincy Adams, the American ambassador in Russia, her sentiments appeared to be as much the result of personal resentment against Bonaparte as of her general views of public affairs. She complained that he would not let her live in peace anywhere, merely because she had not praised him in her works. She met twice with the tsar Alexander I of Russia who "related to me also the lessons a la Machiavelli which Napoleon had thought proper to give him."[94]

"You see," said he, "I am careful to keep my ministers and generals at variance among themselves, in order that each may reveal to me the faults of the other; I keep up a continual jealousy by the manner I treat those who care about me: one day one thinks himself the favourite, the next day another, so that no one is ever certain of my favour."[95]

For de Staël, that was a vulgar and vicious theory. General Kutuzov sent her letters from the Battle of Tarutino; before the end of that year he succeeded, aided by the extreme weather, in chasing the Grande Armée out of Russia.[96]

After four months of travel, de Staël arrived in Sweden. In 1811, she began writing her "Ten Years' Exile", detailing her travels and encounters. She traveled to Stockholm the following year, and continued work there.[97] She did not finish the manuscript and after eight months, she set out for England, without August Schlegel, who meanwhile had been appointed secretary to the Crown Prince Carl Johan, formerly French Marshal Jean Baptiste Bernadotte (She supported Bernadotte as the new ruler of France, as she hoped he would introduce a constitutional monarchy).[98] In London she received a great welcome. She met Lord Byron, William Wilberforce, the abolitionist, and Sir Humphry Davy, the chemist and inventor. According to Byron, "She preached English politics to the first of our English Whig politicians ... preached politics no less to our Tory politicians the day after."[99] In March 1814 she invited Wilberforce for dinner and devoted the remaining years of her life to the fight for the abolition of the slave trade.[100] Her stay was severely marred by the death of her son Albert, who as a member of the Swedish army had fallen in a duel with a Cossack officer in Doberan as a result of a gambling dispute. In October John Murray published De l'Allemagne both in French and English translation, in which she reflected on nationalism and suggested a re-consideration of cultural rather than natural boundaries.[101] In May 1814, after Louis XVIII had been crowned (Bourbon Restoration) she returned to Paris. She wrote her Considérations sur la révolution française, based on Part One of "Ten Years' Exile". Again her salon became a major attraction both for Parisians and foreigners.

Restoration and death[edit]

When news came of Napoleon's landing on the Côte d'Azur, between Cannes and Antibes, early in March 1815, de Staël fled again to Coppet, and never forgave Constant for approving of Napoleon's return.[102] Although she had no affection for the Bourbons she succeeded in obtaining restitution for the huge loan Necker had made to the French state in 1778 before the Revolution (see above).[103] In October, after the Battle of Waterloo, she set out for Italy, not only for the sake of her own health but for that of her second husband, de Rocca, who was suffering from tuberculosis. In May her 19-year-old daughter Albertine married Victor, 3rd duc de Broglie in Livorno.

The whole family returned to Coppet in June. Lord Byron, at that time in debt, left London in great trouble and frequently visited de Staël during July and August. For Byron, she was Europe's greatest living writer, but "with her pen behind her ears and her mouth full of ink". "Byron was particularly critical of de Staël's self-dramatizing tendencies".[104][105] Byron was a supporter of Napoleon, but for de Staël Bonaparte "was not only a talented man but also one who represented a whole pernicious system of power", a system that "ought to be examined as a great political problem relevant to many generations."[106] "Napoleon imposed standards of homogeneity on Europe that is, French taste in literature, art and the legal systems, all of which de Staël saw as inimical to her cosmopolitan point of view."[105] Byron wrote she was "sometimes right and often wrong about Italy and England – but almost always true in delineating the heart, which is of but one nation of no country, or rather, of all."[107]

Despite her increasingly ill health, de Staël returned to Paris for the winter of 1816–17, living at 40, rue des Mathurins. Constant argued with de Staël, who had asked him to pay off his debts to her. A warm friendship sprang up between de Staël and the Duke of Wellington, whom she had first met in 1814, and she used her influence with him to have the size of the Army of Occupation greatly reduced.[108]

De Staël became confined to her house, paralyzed since 21 February 1817 following a stroke. She died on 14 July 1817. Her deathbed conversion to Roman Catholicism, after reading Thomas à Kempis, was reported[citation needed] but is subject to some debate. Wellington remarked that, while he knew that she was greatly afraid of death, he had thought her incapable of believing in the afterlife.[108] Wellington makes no mention of de Staël reading Thomas à Kempis in the quote found in Elizabeth Longford's biography of the Iron Duke. Furthermore, he reports hearsay, which may explain why two modern biographies of de Staël – Herold and Fairweather – discount the conversion entirely. Herold states that "her last deed in life was to reaffirm in her 'Considerations, her faith in Enlightenment, freedom, and progress'."[109] Rocca survived her by little more than six months.

Offspring[edit]

Besides two daughters, Gustava Sofia Magdalena (born July 1787) and Gustava Hedvig (born August 1789), both died in infancy, de Staël had two sons, Ludwig August (1790–1827), Albert (1792–1813), and a daughter, Albertine, baroness Staël von Holstein (1797–1838). It is believed Louis, Comte de Narbonne-Lara was the father of Ludvig August and Albert, and Benjamin Constant the father of red-haired Albertine.[110] With Albert de Rocca, de Staël then aged 46, had one son, the disabled Louis-Alphonse de Rocca (1812–1842), who married Marie-Louise-Antoinette de Rambuteau, daughter of Claude-Philibert Barthelot de Rambuteau,[48] and granddaughter of De Narbonne.[111] Even as she gave birth, there were fifteen people in her bedroom.[112]

After the death of de Staël's husband, Mathieu de Montmorency became the legal guardian of her children. Like August Schlegel he was one of her intimates until the end of her life.

Legacy[edit]

Albertine Necker de Saussure, married to de Staël's cousin, wrote her biography in 1821 and published it as part of the collected works. Auguste Comte included Mme de Staël in his 1849 Calendar of Great Men. "In one version of the calendar, the 24th day of the month of Dante is dedicated to Madame de Staël, who finds herself among such poets as Milton, Cervantes, and Chaucer. In another version, Staël finds herself honored, instead, on the 19th day of the tenth month, known as “Shakespeare,” among the likes of Goethe, Racine, Voltaire, and Madame de Sevigné."[113] Her political legacy has been generally identified with a stout defence of "liberal" values: equality, individual freedom, and the limitation of state power by constitutional rules.[114] "Yet although she insisted to the Duke of Wellington that she needed politics in order to live, her attitude towards the propriety of female political engagement varied: at times she declared that women should simply be the guardians of domestic space for the opposite sex, while at others, that denying women access to the public sphere of activism and engagement was an abuse of human rights. This paradox partly explains the persona of the "homme-femme" she presented in society, and it remained unresolved throughout her life."[115]

Comte's disciple Frederic Harrison wrote about de Staël that her novels "precede the works of Walter Scott, Byron, Mary Shelley, and partly those of Chateaubriand, their historical importance is great in the development of modern Romanticism, of the romance of the heart, the delight in nature, and in the arts, antiquities, and history of Europe."

Precursor of feminism[edit]

Recent studies by historians, including feminists, have been assessing the specifically feminine dimension in de Staël's contributions both as an activist-theorist and as a writer about the tumultuous events of her time.[116][117] Some scholars call her a precursor of feminism.[118][119][120] Staël had a robust theory of female liberation. At the time that Staël was writing, in the peak years of the French Revolution, early French feminism was animated over the issue of legal and political equality for the sexes. At the advent of the French Revolution in 1789, the image of a traditional homemaking woman had given way to a more militant feminist approach found in pamphlets that circulated in France at the time. In this sea of tumultuous events, Staël’s use of the novel and more implicit methods to communicate her beliefs about the Revolution and gender equality, coupled with her social status, aided in ensuring her endurance on the political and literary scene.[121] Staël’s extensive set of writings, from her correspondence with lovers to her philosophy to her fiction, betray not just the tension between intellectual and romantic fulfillment but also between feminist political equality and romantic fulfillment. Her work indicates that she finds her two desires, personal freedom and emotional intimacy, to be diametrically opposed in practice, especially in post-Revolutionary French society. In particular, she deplored the fact that men took the central roles in Enlightenment philosophy and politics, neither of which included avenues for women’s direct participation. [122]

Abolition[edit]

Staël was a strong advocate for the abolition of slavery in the French colonies. In her later years, her salon was frequented by abolitionists, and emancipation was a recurring topic of their discussions. After meeting the famous abolitionist William Wilberforce in 1814, Staël published a preface for his essay on the slave trade in which she called for the end of slavery in Europe. In that text, Staël argued in particular against those who defended slavery on the grounds that the economic impact of abandoning the slave trade would be too grave:

"When it is proposed that some abuse of power be eliminated, those who benefit from that abuse are certain to declare that all the benefits of the social order are attached to it. ‘This is the keystone,’ they say, while it is only the keystone to their own advantages; and when at last the progress of enlightenment brings about the long-desired reform, they are astonished at the improvements which result from it. Good sends out its roots everywhere; equilibrium is effortlessly restored; and truth heals the ills of the human species, as does nature, without anyone’s intervention." (Kadish and Massardier-Kenney 2009, 169)

Staël argues here that the claim that abolition would have “dire consequences” for the French economy is nothing but an illusory threat used by those who benefit from the institution of slavery (Kadish and Massardier-Kenney 2009, 169). Staël believed that the termination of the slave trade would improve France and bring about a positive consequence that ‘sends out its roots everywhere.[89]

Letters to Jefferson[edit]

In 1807, Jacques Le Ray de Chaumont sent Jefferson a copy of Corinne, and also conveyed to Staël Jefferson’s first letter addressed to her. This marked the beginning of a series of eight letters between the two, the last of which was sent from Staël to Jefferson shortly before her passing in 1817.

The correspondence between Staël and Jefferson sheds light upon the fascinating relationship between two momentous figures, covering the personal (such as Staël’s son Auguste’s desire to visit the United States to “make a pilgrimage toward reason and freedom”) and the global (the War of 1812 is the pressing topic, and there is even an interlude where Jefferson details the state of South American geopolitics, replete with a map).

Famously, in 1816, in a letter to Thomas Jefferson, Staël writes, “If one succeeds in destroying slavery in the South, at least one government in the world will be as perfect as human reason can possibly conceive.” Although this is generally understood by scholars to be a criticism of slavery in the southern states of the United States, due to ambiguity in translating the word "south" from the original French, other scholars have suggested that de Staël could be referring to colonization in South America.[123]

Staël and the Adams family[edit]

The Adams family (including former American presidents John Adams and John Quincy Adams and former First Lady Abigail Adams) was an important political family in the U.S during the 18th and early 20th century. Staël was a frequent topic of discussion amongst the Adams. John Quincy Adams, the 6th U.S president, in particular, recommended and sent many copies of Staël’s works to his father, John Adams; mother, Abigail Adams; and wife, Louisa Catherine Adams. In letters written between the end of the 18th century and beginning of the 19th century, these members of the Adams family discussed Delphine, A Treatise on the Influence of the Passions, Upon the Happiness of Individuals and of Nations, and The Reflections Upon Peace.[91]

In popular culture[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Liberalism |

|---|

|

Works[edit]

- Journal de Jeunesse, 1785

- Sophie ou les sentiments secrets, 1786 (published anonymously in 1790)

- Jane Gray, 1787 (published in 1790)

- Lettres sur le caractère et les écrits de J.-J. Rousseau, 1788[134]

- Éloge de M. de Guibert

- À quels signes peut-on reconnaître quelle est l'opinion de la majorité de la nation?

- Réflexions sur le procès de la Reine, 1793

- Zulma : fragment d'un ouvrage, 1794

- Réflexions sur la paix adressées à M. Pitt et aux Français, 1795

- Réflexions sur la paix intérieure

- Recueil de morceaux détachés (comprenant : Épître au malheur ou Adèle et Édouard, Essai sur les fictions et trois nouvelles : Mirza ou lettre d'un voyageur, Adélaïde et Théodore et Histoire de Pauline), 1795

- Essai sur les fictions, translated by Goethe into German

- De l'influence des passions sur le bonheur des individus et des nations, 1796[135]

- Des circonstances actuelles qui peuvent terminer la Révolution et des principes qui doivent fonder la République en France

- De la littérature dans ses rapports avec les institutions sociales, 1799

- Delphine, 1802 deals with the question of woman's status in a society hidebound by convention and faced with a Revolutionary new order

- Vie privée de Mr. Necker, 1804

- Épîtres sur Naples

- Corinne ou l'Italie, 1807 is as much a travelogue as a fictional narrative. It discusses the problems of female artistic creativity in two radically different cultures, England and Italy.

- Agar dans le désert

- Geneviève de Brabant

- La Sunamite

- Le capitaine Kernadec ou sept années en un jour (comédie en deux actes et en prose)

- La signora Fantastici

- Le mannequin (comédie)

- Sapho

- De l'Allemagne, 1813, translated as Germany 1813.[136]

- Réflexions sur le suicide, 1813

- Morgan et trois nouvelles, 1813

- De l'esprit des traductions

- Considérations sur les principaux événements de la révolution française, depuis son origine jusques et compris le 8 juillet 1815, 1818 (posthumously)[137]

- Dix Années d'Exil (1818), posthumously published in France by Mdm Necker de Saussure. In 1821 translated and published as Ten Years' Exile. Memoirs of That Interesting Period of the Life of the Baroness De Stael-Holstein, Written by Herself, during the Years 1810, 1811, 1812, and 1813, and Now First Published from the Original Manuscript, by Her Son.[138]

- Essais dramatiques, 1821

- Oeuvres complètes 17 t., 1820–21

- Oeuvres complètes de Madame la Baronne de Staël-Holstein [Complete works of Madame Baron de Staël-Holstein]. Paris: Firmin Didot frères. 1836. Volume 1 · Volume 2

Correspondence in French[edit]

- Lettres de Madame de Staël à Madame de Récamier, première édition intégrale, présentées et annotées par Emmanuel Beau de Loménie, éditions Domat, Paris, 1952.

- Lettres sur les écrits et le caractère de J.-J. Rousseau. – De l'influence des passions sur le bonheur des individus et des nations. – De l'éducation de l'âme par la vie./Réflexions sur le suicide. – Sous la direction de Florence Lotterie. Textes établis et présentés par Florence Lotterie. Annotation par Anne Amend Söchting, Anne Brousteau, Florence Lotterie, Laurence Vanoflen. 2008. ISBN 978-2745316424.

- Correspondance générale. Texte établi et présenté par Béatrice W. Jasinski et Othenin d'Haussonville. Slatkine (Réimpression), 2008–2009.

- Volume I. 1777–1791. ISBN 978-2051020817.

- Volume II. 1792–1794. ISBN 978-2051020824.

- Volume III. 1794–1796. ISBN 978-2051020831.

- Volume IV. 1796–1803. ISBN 978-2051020848.

- Volume V. 1803–1805. ISBN 978-2051020855.

- Volume VI. 1805–1809. ISBN 978-2051020862.

- Volume VII. date:15 May 1809–23 May 1812. ISBN 978-2051020879.

- Madame de Staël ou l'intelligence politique. Sa pensée, ses amis, ses amants, ses ennemis…, textes de présentation et de liaison de Michel Aubouin, Omnibus, 2017. ISBN 978-2258142671 commentaire biblio, Lettres de Mme de Staël, extraits de ses textes politiques et de ses romans, textes et extraits de lettres de Chateaubriand, Talleyrand, Napoléon, Benjamin Constant. This edition contains extracts from her political writings and from letters addressed to her by Chateaubriand, Talleyrand, Napoleon and Benjamin Constant.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Wilkinson, L. R. (2017). Hibbitt, Richard (ed.). Other Capitals of the Nineteenth Century An Alternative Mapping of Literary and Cultural Space. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 51–67.

- ^ Simon, Sherry (2003). Gender in Translation. Routledge. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-1134820863.

- ^ Staël, Germaine de, in the Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ^ a b c d e Bordoni, Silvia (2005) Lord Byron and Germaine de Staël, The University of Nottingham

- ^ Madame de Staël (Anne-Louise-Germaine) (1818). Considerations on the Principal Events of the French Revolution: Posthumous Work of the Baroness de Stael. James Eastburn and Company at the literary rooms, Broadway. Clayton & Kingsland, Printers. p. 46.

- ^ a b "Madame de Staël".

- ^ "Germaine de Staël - Exile, Novels, Enlightenment | Britannica".

- ^ Eveline Groot – Public Opinion and Political Passions in the Work of Germaine de Stäel, p. 190

- ^ a b Saintsbury 1911, p. 750.

- ^ Casillo, R. (2006). The Empire of Stereotypes: Germaine de Staël and the Idea of Italy. Springer. ISBN 978-1403983213.

- ^ Gabriel Paul Othenin de Cléron, (Comte d'Haussonville) (1882) The Salon of Madame Necker. Trans. Henry M. Trollope. London: Chapman and Hall.

- ^ a b c "Vaud: Le château de Mezery a Jouxtens-Mezery".

- ^ a b "Stael and the French Revolution | Online Library of Liberty". oll.libertyfund.org. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ Niebuhr, Barthold Georg; Michaelis, Johann David (1836). The Life of Carsten Niebuhr, the Oriental Traveller. T. Clark. p. 6.

- ^ Schama, p. 257

- ^ Dixon, Sergine (2007). Germaine de Staël, daughter of the enlightenment: the writer and her turbulent era. Amherts (N.Y.): Prometheus books. ISBN 978-1-59102-560-3.

- ^ Napoleon's nemesis

- ^ Grimm, Friedrich Melchior; Diderot, Denis (1815). Historical & literary memoirs and anecdotes. Printed for H. Colburn. p. 353.

- ^ "Germaine de Staël | Books, Biography, & Facts | Britannica". 18 April 2024.

- ^ Schama, pp. 345–346.

- ^ Schama, p. 382

- ^ Schama, pp. 499, 536

- ^ Craiutu, Aurelian A Voice of Moderation in the Age of Revolutions: Jacques Necker's Reflections on Executive Power in Modern Society. p. 4

- ^ The Works of John Moore, M.D.: With Memoirs of His Life and Writings, Band 4 by John Moore (1820)

- ^ d’Haussonville, Othénin (2004) "La liquidation du ‘dépôt’ de Necker: entre concept et idée-force", pp. 156–158 Cahiers staëliens, 55

- ^ Fontana, p. 29

- ^ Fontana, p. 33

- ^ Fontana, pp. 37, 41, 44

- ^ Correspondance (1770–1793). Published by Évelyne Lever. Paris 2005, pp. 660, 724

- ^ Fontana, p. 49

- ^ "Mémoires de Malouet", p. 221

- ^ Schama, pp. 624, 631

- ^ Fontana, p. 61

- ^ Moore, p. 138

- ^ Herold, p. 272

- ^ Madame de Staël (Anne-Louise-Germaine) (1818). Considerations on the Principal Events of the French Revolution. Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy. p. 75.

- ^ Ballard, Richard (2011). A New Dictionary of the French Revolution. I.B. Tauris. p. 341. ISBN 978-0857720900.

- ^ It was Tallien who announced the September Massacres and sent off the famous circular of 3 September to the French provinces, recommending them to take similar action.

- ^ a b Anne Louise Germaine de Staël (2012). Selected Correspondence. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 110. ISBN 978-9401142830.

- ^ "Staël (1766-1817)".

- ^ "Staël (1766-1817)".

- ^ Moore, p. 15

- ^ Fontana, p. 113

- ^ The Thermidorians had opened the way back to Paris.

- ^ Fontana, p. 125

- ^ Müller, p. 29.

- ^ Team, Project Vox. "Germaine de Staël (1766-1817)". Project Vox. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Anne-Louise-Germaine Necker, Baroness de Staël-Holstein (1766–1817) by Petri Liukkonen

- ^ Moore, p. 332

- ^ Fontana, p. 178; Moore, p. 335

- ^ Moore, pp. 345, 349

- ^ Custine, Delphine de Custine, 66, note 1.

- ^ Fontana, p.159

- ^ Les clubs contre-révolutionnaires, cercles, comités, sociétés ..., Band 1 von Augustin Challamel, S. 507-511

- ^ Fontana, p. 159

- ^ Moore, p. 348

- ^ Moore, pp. 350–352

- ^ Madame de Staël (Anne-Louise-Germaine) (1818). Considerations on the Principal Events of the French Revolution: Posthumous Work of the Baroness de Stael. James Eastburn and Company at the literary rooms, Broadway. Clayton & Kingsland, Printers. pp. 90, 95–96.

- ^ Madame de Staël (1818). Considerations on the Principal Events of the French Revolution: Posthumous Work of the Baroness de Stael. James Eastburn and Company at the literary rooms, Broadway. Clayton & Kingsland, Printers. p. 42.

- ^ Goodden, p. 18

- ^ Moore, p. 379

- ^ Memoirs of Madame de Remusat, trans. Cashel Hoey and John Lillie, p. 407. Books.Google.com

- ^ Saintsbury 1911, p. 751.

- ^ Delphine (1802), Préface

- ^ From the Introduction to Madame de Staël (1987) Delphine. Edition critique par S. Balayé & L. Omacini. Librairie Droz S.A. Genève

- ^ Fontana, p. 204

- ^ "Un journaliste contre-révolutionnaire, Jean-Gabriel Peltier (1760–1825) – Etudes Révolutionnaires". Etudes-revolutionnaires.org. 7 October 2011. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- ^ Fontana, p. 263, note 47

- ^ Fontana, p. 205

- ^ Müller, p. 292

- ^ Sainte-Beuve, Charles Augustin (1891). Portraits of Women. A. C. M'Clurg. p. 107.

- ^ Jonas, Fritz, ed. (1892). Schillers Briefe. Kritische Gesamtausgabe. Vol VII. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt. p. 109.

- ^ Graf, Hans Gerhard; Leitzmann, Albert, eds. (1955). Der Briefwechsel zwischen Schiller und Goethe. Leipzig. pp. 474–485.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Madame de Staël von Klaus-Werner Haupt

- ^ Herold, p. 304

- ^ Panizza, Letizia; Wood, Sharon. A History of Women's Writing in Italy. p. 144.

- ^ The novel prompted, none too inspiringly, The Corinna of England, and a Heroine in the Shade (1809) by E. M. Foster, in which retribution is wreaked on a shallowly portrayed version of the French author's heroine.

- ^ Team, Project Vox. "Germaine de Staël (1766-1817)". Project Vox. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ Goodden, p. 61

- ^ Fontana, p. 230

- ^ Herold, p. 290

- ^ Stevens, A. (1881). Madame de Stael: A Study of her Life and Times, the First Revolution and the First Empire. London: John Murray. pp. 15–23.

- ^ Schlegel and Madame de Staël have endeavoured to reduce poetry to two systems, classical and romantic.

- ^ Ferber, Michael (2010) Romanticism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199568918.

- ^ Madame de Staël et Maurice O’Donnell (1805–1817), d’apres des letters inédites, by Jean Mistler, published by Calmann-Levy, Editeurs, 3 rue Auber, Paris, 1926.

- ^ Goodden, p. 73

- ^ Müller

- ^ a b Fontana, p. 206

- ^ a b Team, Project Vox. "Germaine de Staël (1766-1817)". Project Vox. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ Staël (Anne-Louise-Germaine, Madame de); Auguste Louis Staël-Holstein (baron de) (1821). Ten years' exile: or, Memoirs of that interesting period of the life of the Baroness de Stael-Holstein. Printed for Treuttel and Würtz. pp. 101–110.

- ^ a b Team, Project Vox. "Germaine de Staël (1766-1817)". Project Vox. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ Ten Years' After, p. 219, 224, 264, 268, 271

- ^ Ten Years' Exile, pp. 350–352

- ^ Ten Years' Exile, p. 421

- ^ Ten Years' Exile, p. 380

- ^ Tolstoy, Leo (2017). The Complete Works of Leo Tolstoy. Musaicum Books. pp. 2583–. ISBN 978-8075834553.

- ^ Team, Project Vox. "Germaine de Staël (1766-1817)". Project Vox. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ Zamoyski, Adam. (2007) Rites of Peace. The fall of Napoleon & the Congress of Vienna. Harper Perennial. p. 105. ISBN 978-0060775193

- ^ Nicholson, pp. 184–185

- ^ Autograph letter in French, signed 'N. de Staël H' to William Wilberforce

- ^ Lord Byron and Germaine de Staël by Silvia Bordoni, p. 4

- ^ Fontana, p. 227.

- ^ Fontana, p. 208.

- ^ BLJ, 8 January 1814; 4:19.

- ^ a b Wilkes, Joanne (1999). Lord Byron and Madame de Staël: Born for Opposition. London: Ashgate. ISBN 1840146990.

- ^ de Staël, Germaine (2008). Craiutu, Aurelian (ed.). Considerations on the Principal Events of the French Revolution: Newly Revised Translation of the 1818 English Edition (PDF). Indianapolis: Liberty Fund. p. xvii. ISBN 978-0865977310.

- ^ Nicholson, pp. 223–224

- ^ a b Longford, Elizabeth (1972). Wellington: Pillar of State. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 38.

- ^ Herold, p. 392

- ^ Goodden, p. 31

- ^ Moore, p. 390

- ^ Moore, p. 8

- ^ Project Vox Team (17 April 2024). "Staël (1766-1817)".

- ^ Fontana, p. 234.

- ^ Goodden, Angelica (2007). "The Man-Woman and the Idiot: Madame de Staël's Public/Private Life". Forum for Modern Language Studies. 43 (1): 34–45. doi:10.1093/fmls/cql117.

- ^ Marso, Lori J. (2002). "Defending the Queen: Wollstonecraft and Staël on the Politics of Sensibility and Feminine Difference". The Eighteenth Century. 43 (1). University of Pennsylvania Press: 43–60. JSTOR 41468201.

- ^ Moore, L. (2007). Liberty: The Lives and Times of Six Women in Revolutionary France.

- ^ Popowicz, Kamil (2013). Madame de Staël (in Polish). Vol. 4. Warsaw: Collegium Civitas.

- ^ Casillo, R. (2006). The Empire of Stereotypes: Germaine de Staël and the Idea of Italy. Springer. p. 1. ISBN 978-1403983213.

- ^ Powell, Sara (1994). "Women Writers in Revolution: Feminism in Germaine de Staël and Ding Ling". Masters Theses & Specialist Projects. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- ^ "Staël (1766-1817)".

- ^ "Staël (1766-1817)".

- ^ Team, Project Vox. "Germaine de Staël (1766-1817)". Project Vox. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ Abramowitz, Michael (2 April 2007). "Rightist Indignation". Washington Post. Retrieved 30 June 2007.

- ^ Hasty, Olga Peters (1999). Pushkin's Tatiana. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 245. ISBN 978-0299164041.

- ^ Vincent, Patrick H. (2004). The Romantic Poetess: European Culture, Politics, and Gender, 1820–1840. UPNE. pp. 79–80. ISBN 978-1584654308.

- ^ Rossettini, Olga (1963). "Madame de Staël et la Russie". Rivista de Letterature Moderne e Comparate. 16 (1): 50–67.

- ^ "Emerson – Roots – Madame DeStael". transcendentalism-legacy.tamu.edu. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ^ Porte, Joel (1991). In Respect to Egotism: Studies in American Romantic Writing. Cambridge University Press. p. 23.

- ^ Moi, Toril (2006). Henrik Ibsen and the Birth of Modernism: Art, Theater, Philosophy. Oxford University Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0199295876.

- ^ Moore, p. 350

- ^ Sämtliche Schriften (Anm. 2), Bd. 3, S. 882 f.

- ^ Nicholson, p. 222

- ^ Lettres sur la Caractère et les Écrits de Jean-Jacques Rousseau

- ^ A Treatise on the influence of Passions on the Happiness of individuals and of nations

- ^ Madame de Staël (Anne-Louise-Germaine) (1813). Germany. John Murray. pp. 1–.

- ^ Considérations sur les principaux événements de la révolution française

- ^ Ten Years' Exile by Madame de Staël

Sources[edit]

- Fontana, Biancamaria (2016). Germaine de Staël: A Political Portrait. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691169040.

- Goodden, Angelica (2008). Madame de Staël : the dangerous exile. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199238095.

- Herold, J. Christopher (2002). Mistress to an Age: A Life of Madame de Staël. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0802138378.

- Moore, L. (2007). Liberty. The Lives and Times of Six Women in Revolutionary France.

- Müller, Olaf (2008). "Madame de Staël und Weimar. Europäische Dimensionen einer Begegnung" (PDF). In Hellmut Th. Seemann (ed.). Europa in Weimar. Visionen eines Kontinents. Jahrbuch der Klassik Stiftung Weimar. Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag.

- Nicholson, Andrew, ed. (1991). Lord Byron: The Complete Miscellaneous Prose. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0198185437.

- Schama, Simon (1989). Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. Random House. ISBN 0679-726101.

Further reading[edit]

- Bredin, Jean-Denis. Une singulière famille: Jacques Necker, Suzanne Necker et Germaine de Staël. Paris: Fayard, 1999 (ISBN 2213602808) (in French)

- Casillo, Robert (2006). The Empire of Stereotypes. Germaine de Stael and the Idea of Italy. London: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 1349533688.

- Daquin, Françoise Marie Danielle (2020) Slavery and feminism in the writings of Madame de Staël. https://doi.org/10.25903/5f07e50eaaa2b

- Fairweather, Maria. Madame de Staël. New York: Carroll & Graf, 2005 (hardcover, ISBN 0786713399); 2006 (paperback, ISBN 078671705-X); London: Constable & Robinson, 2005 (hardcover, ISBN 1841198161); 2006 (paperback, ISBN 1845292278).

- Garonna, Paolo (2010). L'Europe de Coppet – Essai sur l'Europe de demain (in French). Le Mont-sur-Lausanne: LEP Éditions Loisirs et Pėdagogie. ISBN 978-2606013691.

- Hilt, Douglas. "Madame De Staël: Emotion and Emancipation". History Today (Dec 1972), Vol. 22 Issue 12, pp. 833–842, online.

- Hofmann, Étienne, ed. (1982). Benjamin Constant, Madame de Staël et le Groupe de Coppet: Actes du Deuxième Congrès de Lausanne à l'occasion du 150e anniversaire de la mort de Benjamin Constant Et Du Troisième Colloque de Coppet, 15–19 juilliet 1980 (in French). Oxford, The Voltaire Foundation and Lausanne, Institut Benjamin Constant. ISBN 0729402800.

- Levaillant, Maurice (1958). The passionate exiles: Madame de Staël and Madame Récamier. Farrar, Straus and Cudahy. ISBN 978-0836980868.

- Sluga, Glenda (2014). "Madame de Staël and the Transformation of European Politics, 1812–17". The International History Review. 37: 142–166. doi:10.1080/07075332.2013.852607. hdl:2123/25775. S2CID 144713712.

- Winegarten, Renee. Germaine de Staël & Benjamin Constant: A Dual Biography. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008 (ISBN 978-0300119251).

- Winegarten, Renee. Mme. de Staël. Dover, NH: Berg, 1985 (ISBN 0907582877).

External links[edit]

- Stael and the French Revolution Introduction by Aurelian Craiutu

- BBC4 In Our Time on Germaine de Staël

- Madame de Staël and the Transformation of European Politics, 1812–17 by Glenda Sluga. In: The International history review 37(1):142–166 · November 2014

- (in French) Stael.org, with detailed chronology

- (in French) BNF.fr (Searching "stael").

- Works by Germaine de Staël at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Germaine de Staël at Internet Archive

- Works by Germaine de Staël at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- "Staël, Germaine de" in The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition: 2001–05.

- The Great de Staël by Richard Holmes from The New York Review of Books

- http://www.dieterwunderlich.de/madame_Germaine_de_Stael.htm (in German)

Corinne at the Cape of Misena. is a painting by Baron Gerard with illustrative verse by Letitia Elizabeth Landon, which shows Madame de Staël as Corinne. The poem includes a translation of part of Corinne's song at Naples.

Corinne at the Cape of Misena. is a painting by Baron Gerard with illustrative verse by Letitia Elizabeth Landon, which shows Madame de Staël as Corinne. The poem includes a translation of part of Corinne's song at Naples. Corinna at the Capitol. by Felicia Hemans has two versions of the poem.

Corinna at the Capitol. by Felicia Hemans has two versions of the poem.- Saintsbury, George (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 750–752.

- 1766 births

- 1817 deaths

- Writers from Paris

- Writers from the Republic of Geneva

- Women in the French Revolution

- People of the First French Empire

- 18th-century French women writers

- 18th-century philosophers

- 18th-century French letter writers

- 19th-century French letter writers

- 19th-century French women writers

- 19th-century French novelists

- 19th-century Swiss women writers

- 19th-century French philosophers

- French Roman Catholics

- French women philosophers

- French literary critics

- French feminists

- French travel writers

- French women novelists

- Converts to Roman Catholicism from Calvinism

- Coppet group

- Swiss feminists

- Swiss writers in French

- Swedish nobility

- French women literary critics

- Swedish women literary critics

- Women historical novelists

- Women travel writers

- Conversationalists

- Romanticism

- French salon-holders