Talk:Orange Order/sandbox

It has been created to assist editors seeking to reach consensus on the article's contents

The Orange Institution, more commonly known as the Orange Order or the Orange Lodge, is a Protestant fraternal organisation based predominantly in Northern Ireland and Scotland with lodges throughout the Commonwealth and the United States. It was founded in Loughgall, County Armagh, Ireland in 1795; its name is a tribute to Dutch-born Protestant king of England, William III, of the House of Orange-Nassau. William had defeated the Catholic army of James II at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. Observers have accused the Orange Institution of being a sectarian organisation, due to its goals and exclusion of Roman Catholics as members.[1][2][3]

The Twelfth[edit]

The highlights of the Orange year are the parades leading up to the celebrations on the Twelfth of July. The Twelfth, however, remains in places a deeply divisive issue, not least because of the triumphalism and anti-Catholicism of the Orange Order in the conduct of its Walks and criticism of its behaviour towards Roman Catholics. [4] [5]

In recent years, most Orange parades have passed peacefully.[6] [7][8]

Grand Orange Lodge of Ireland[edit]

The Grand Orange Lodge of Ireland is the governing body of the Orange Order in Ireland. It has 373 members, 250 of whom are appointed by County Lodges. Its Central Committee is made up of three members from each of the six counties of Northern Ireland (Londonderry, Antrim, Down, Tyrone, Armagh, and Fermanagh) as well as the two other County Lodges in Northern Ireland, the City of Belfast Grand Lodge and the City of Londonderry Grand Lodge, two each from the remaining Ulster counties (Cavan, Donegal, and Monaghan), one from Leitrim, and 19 others.

Requirements for entry[edit]

Members are required to be Protestant with a belief in the Trinity. This excludes Catholics, Unitarians and certain other Christian denominations and all non-Christians.[9] Most jurisdictions require both the spouse and parents of potential applicants to be Protestant, although the Grand Lodge can be appealed to make exceptions for converts. Members of the Order face the threat of expulsion for attending any Catholic religious ceremonies.

The Laws and Constitutions of the Loyal Orange Institution of Scotland of 1986 state, "No ex-Roman Catholic will be admitted into the Institution unless he is a Communicant in a Protestant Church for a reasonable period." Likewise, the "Constitution, Laws and Ordinances of the Loyal Orange Institution of Ireland" (1967) state, "No person who at any time has been a Roman Catholic … shall be admitted into the Institution, except after permission given by a vote of seventy five per cent of the members present founded on testimonials of good character …" In the 19th century, Rev. Dr. Mortimer O'Sullivan, a converted Roman Catholic was a Grand Chaplain of the Orange Order in Ireland.

In the 1950s, Scotland also had a converted Roman Catholic as a Grand Chaplain—Rev. William McDermott.

Religion and culture[edit]

Protestantism[edit]

The basis of the modern Orange Order is the promotion and propagation of "biblical Protestantism" and the principles of the Reformation. As such the Order only accepts those who confess a belief in a Protestant religion.

The Order considers the Fourth Commandment to forbid Christians to work on Sundays. In March 2002 it threatened "to take every action necessary, regardless of the consequences" to prevent the Ballymena Show being held on a Sunday. The County Antrim Agricultural Association immediately complied with the Order's wishes.[citation needed]

Some evangelical groups have come forward with what are clearly baseless claim that the Orange Order is still influenced by Freemasonry.[10] Many Masonic usages survive such as the organisation of the Order into lodges. The Order has a system of degrees through which new members advance. These degrees are interactive plays with references to the Bible. There is particular concern over the ritualism of higher degrees such as the Royal Arch Purple and the Royal Black Institutions.[11] However, it would be fair to say that such attitudes are merely those of extremist evangelical groups and do not reflect the true situation.

Parades and Orange Halls[edit]

Parades form a large part of Orange culture. Most Orange lodges hold an annual parade from their Orange Hall to a local church. The denomination of the church is quite often rotated, depending on local demographics.

Monthly meetings are held in Orange Halls. Orange Halls on both sides of the Irish border often function as community halls for Protestants and sometimes those of other faiths, though this was more common in the past[12]. The halls quite often host community groups such as credit unions, local marching bands, Ulster Scots and other cultural groups as well as religious missions and Unionist political parties.

Orange Halls have often[specify] been the target of vandalism, paint bombings, graffiti and arson attacks, on one occasion by a member of Ógra Shinn Féin[13] with many[specify] of the halls suffering severe damage, if not complete destruction[14][15]. The Order claims that there is considerable evidence of an organised campaign of sectarian vandalism by republicans.[citation needed] For GIS maps of Orange halls in Northern Ireland and elsewhere, see Eric Kaufmann's Orange Order Page.

As of 2007, Grand Lodge of Ireland policy remained non-recognition of the N.I. Parades Commission, which it sees as explicitly founded to target Protestant culture since Protestants parade at ten times the rate of Catholics. Grand Lodge is, however, divided on the issue of working with the Parades Commission. 40% of Grand Lodge delegates oppose official policy while 60% are in favour. Most of those opposed to Grand Lodge policy are from areas facing parade restrictions like Portadown District, Bellaghy, Derry City and Lower Ormeau.[16]

Controversy[edit]

Its spokespeople and supporters describe the Orange Order as a pious organisation, celebrating Protestant culture and identity, but it is accused of sectarianism and anti-Catholicism. The Orange Order is well-known for holding parades, called the Orange Walk, mainly in Ulster, (Northern Ireland and in the Republic of Ireland), Scotland, England and Canada. The parades take place throughout the heated marching season, climaxing on the 12th of July. As a mark of defiance, some members choose to not wear green on Saint Patrick's Day, preferring to wear orange instead. However, in recent years, Saint Patrick's Day has become more of a cross-community event, with several loyalist band parades joining in the commemoration of Saint Patrick. There are at least two Orange Lodges in Northern Ireland which represent the heritage and religious ethos of St Patrick.[citation needed]

James Craig, 1st Viscount Craigavon, as Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, is quoted as stating on April 24 1934 at Stormont, "I have always said that I am an Orangeman first and a politician and a member of this Parliament afterwards—they still boast of Southern Ireland being a Catholic State. All I boast of is that we are a Protestant Parliament and a Protestant State."

[edit]

The Order, from its very inception was an overtly political organisation. [17] [18] [19] [20] Since 1905 the Orange Order was entitled to a voting bloc on the Ulster Unionist Council, the decision-making body of the Ulster Unionist Party. It used this to considerable effect in the Stormont period, and it (and not Paisley) was the force behind the UUP no-confidence votes in reformist Prime Ministers O'Neill (1969), Chichester-Clark (1969–71) and Faulkner (1972–74).[21] Although the UUP had long mulled over breaking the link, it was, in the end, the Orange Order that broke away in March 2005. The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) attracted the most votes in an election for the first time in the 2003. Ian Paisley, who is not a member of the Orange Order, maintained a bitter campaign of conflict with the Order since 1951, when the Order banned members of Paisley's Free Presbyterian Church from acting as Orange chaplains and openly endorsed the Official Unionists (UUP) against independent Unionist parties like Paisley's.[22][23][24] Recently, however, Orangemen have begun voting for Paisley in large numbers due to their opposition to the Good Friday Agreement.[25] Relations between the DUP and Order have healed greatly since 2001, and there are now a number of high profile Orangemen who are DUP MPs and strategists.[26]

There are three related organisations, the Independent Orange Institution (which disapproved of the link with the Official Unionist Party), the Apprentice Boys of Derry (named after Protestant guild apprentices who closed the city gates on a Jacobite army seeking to enter the walled city of Derry in 1688 and helped withstand the siege of Derry), whose roots lie in urban working-class Protestant communities, and the Royal Black Preceptory (RBP). There is some dispute as to the RBP's origins, some suggesting that they are descended from the remnants of the Knights of the Order of St John.

Recently, the Orange Institution has joined with the Royal Black Preceptory and the Independent Orange Institution in talks with the nationalist Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) and the Roman Catholic Church in order to explain the background to Orange parades and demonstrate the Institution's willingness to have dialogue with Catholics. This has been seen by some people as a development of the relationship between the Orange Institution and the Independent Orange Institution which has resulted in the holding of joint church services and which some people believe will ultimately result in a healing of the split which led to the Independent Orange Institution breaking away from the mainstream Order.

Orange charities and societies[edit]

The Orange Order runs a number of charitable ventures including:

- The Grand Orange Lodge of British America Benefit Fund

- Lord Enniskillen Memorial Orange Orphan Society

- Orange Foundation

Throughout the world[edit]

The Orange Institution spread throughout the English-speaking world and further abroad. It is headed by the Imperial Grand Orange Council. It has the power to arbitrate in disputes between Grand Lodges, and in internal disputes when invited. The Council represents the autonomous Grand Lodges of Ireland, Scotland, England, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the United States, Ghana, Togo, and Wales.

Famous Orangemen have included Dr Thomas Barnardo, who joined the Order in Dublin, Sir. John A. Macdonald, who was Prime Minister of Canada, William Massey, who was Prime Minister of New Zealand, Harry Ferguson, inventor of the Ferguson Tractor, and Earl Alexander, the Second World War general.

Republic of Ireland[edit]

The main annual Orange parade in the Republic of Ireland is at Rossnowlagh, County Donegal, an event which has been free from trouble and controversy.[27] The Order has Lodges in Leitrim, Donegal, Cavan, Monaghan, Dublin, Wicklow and West Cork. At one stage there were more than 300 Orange Lodges in Dublin alone. The last July 12th parade in Dublin took place in 1937.

In 2005, controversy was generated when the organisers of Cork's St Patrick's Day parade (in the Republic of Ireland) invited representatives of the Orange Order to parade in the celebrations, part of the year-long celebration of Cork's position of European Capital of Culture. The Orange Order accepted the invitation and was to parade with their wives and children alongside Chinese, Filipino and African community groups in an event designed to recognise and celebrate cultural diversity. A threatening phone call was made to a person connected to the parade’s organising committee. Subsequently, after consultation with the Garda Síochána (the Irish police service), the Orange Order grand secretary Drew Nelson said both his organisation and the parade organisers were disappointed that the Order would not be attending the festivities. He added that he welcomed the invitation and hoped the Order would be able to participate in the event next year. A Church of Ireland clergyman, The Reverend David Armstrong, spoke out against the invitation. Now based in Carrigaline, near Cork, Mr Armstrong and his family were forced to leave their home in Limavady, County Londonderry, by loyalist paramilitaries after he spoke out against the bombing of the local Catholic church. He stated that local Orangemen told him at the time that "the bombing was God's work."[citation needed]

The 2006 Dublin riots were a series of riots which occurred in Dublin on 25 February 2006, precipitated by a controversial Unionist demonstration which was due to parade down O'Connell Street in the city.

England[edit]

Most English lodges are based in the Liverpool area, including Toxteth. An estimated 4,000 Orangemen, women and children parade in Liverpool and Southport every 12 July, watched by tens[citation needed] of thousands more.

History[edit]

The Orange Order has had a presence in Liverpool since at least 1819 when the first parade was held to mark the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne, on July 12. In its early years in the city the Twelfth was known as Carpenters Day due to the abundance of shipwrights who, having emigrated from Belfast, took part. The organisation was not just an association for migrants from Ireland however; their politics ensured that the majority of Orangemen were English-born. Indeed, the Institution in England was started by soldiers returning to the Manchester area from Ireland. The organisation was its strongest in the Toxteth and Everton areas of Liverpool. Many prominent Liverpudlians were members, including, reputedly, the founders of Liverpool Football Club.[citation needed]

In the nineteenth century the movement became very closely linked to the dominant Conservative and Unionist Party although in 1909 the Liverpool Protestant Party was founded by George Wise. The party returned several councilors but became defunct in 1974 after their power base was destroyed. Today, Orange Order members in Liverpool, almost unanimously, vote for the Conservative Party.

At one stage the Order was reputed to have over 40,000 members in Liverpool but the post-war years have seen a steady decline in numbers.[citation needed] The Institution split in 1989 and some members left to attach themselves to the Independent Orange Order after a dispute about paramilitary flags. Today, the combined memberships stand at around 4,000.

Parades[edit]

The Orange Order in Liverpool holds their annual Twelfth parade in Southport, a seaside town north of Liverpool. The Institution also holds a parade there on Whit Monday whilst the Apprentice Boys hold their parade in June, also in Southport. The Black Institution holds their Southport parade on the first Saturday in August.

The Orange Order also parade in Liverpool on the Sunday prior to the Twelfth and on the Sunday after. These parades go to and from church. Other parades are held to commemorate significant events. For example, in July, the Apprentice Boys parade to and from church in commemoration of the Battle of the Somme.

A larger than usual Twelfth parade is being planned for 2008 to mark Liverpool's European Capital of Culture year by the Grand Lodge of England which will be held on Saturday 3rd May 2008.

Scotland[edit]

The Grand Orange Lodge of Scotland is the largest Orange Lodge outside Northern Ireland. Like its cousin in Northern Ireland, the organisation's Grand Lodge has tried to rein in troublemakers within its ranks who have support in some local lodges in order to improve its public image.[citation needed] While almost all parades pass off peacefully among members, opposition groups and by standers following parades can often clash.

Membership is almost entirely working-class, changing little in social composition since the late nineteenth century. Most lodges are concentrated in west central Scotland around Glasgow, Lanark, and parts of Renfrew and Ayr. However, the Order is also very strong in West Lothian, and, to a lesser extent East Lothian, but not in Edinburgh. Lodges are also based in the North East of Scotland, the most northerly lodges are located in Aberdeen, Alford, Peterhead and Inverness. The orders presence in the North of Scotland can be located to the fishing industry and imposition of workers from Belfast and Glasgow to the north and north east and migration of fishermen in the opposite direction.

In 1881, fully three quarters of Orange lodge masters were born in Ireland and, when compared to Canada, Scottish Orangeism has been both smaller (no more than two percent of adult male Protestants in west central Scotland have ever been members) and more of an Ulster ethnic association which has been less attractive to the native Protestant population.[28][29] The strongest predictor of Orange strength in a Scottish county for the period 1860–2001 is the proportion of Irish-Protestant descent in the county.[30]

Scottish Orangeism's political influence crested between the wars, but was effectively nil thereafter as the Tory party at all levels began to move away from Protestant politics toward a more neo-liberal economic agenda.[31]

Scottish Orangeism has come out against Scottish independence, and on 24 March 2007, a parade of 10,000 Orangemen went through Edinburgh's Royal Mile to protest against it.[32]

Wales/Cymru[edit]

Cymru LOL 1922 is at this time the only Orange lodge sitting within the Welsh border.

United States[edit]

In 1871, in New York City, Mayor Hall and Superintendent Kelso, head of the New York Police Department, issued a decree on 10th July banning the 12 July demonstration. Nine people had been killed and more than a hundred injured (including children) during the parade the year before, when a riot broke out after the paraders had angered Irish Catholics with sectarian songs and slogans. The ban appalled many nativists, who saw it as bowing down to the wishes of the Irish Catholic immigrant community. The New York Times had a July 11 headline, Terrorism Rampant. City Authorities Overawed by the Roman Catholics. The ban was revoked by State Governor Hoffman, after pressure from the city's elite. He promised the Orangemen protection by the state and Federal authorities if the city of New York could not provide it.

New Zealand[edit]

Bro. William Ferguson Massey, a native of Limavady who went on to be Prime Minister of New Zealand from 1912–1925, was a member of L.O.L. No.10 Auckland, New Zealand. Lodges paraded on the Twelfth of July until at least the 1920s, but since then the Order has declined in visibility, and most New Zealanders are probably unaware of its existence in their country.

Canada[edit]

The Orange Order played an important role in the history of Canada, where it was established in 1830. Most early members were from Ireland, but later many English, Scots, and other Protestant Europeans joined the Order. Toronto was the epicentre of Canadian Orangeism: most mayors were Orange until the 1950s, and Toronto Orangemen battled against Ottawa-driven initiatives like bilingualism and Catholic immigration. A third of the Ontario legislature was Orange in 1920, but in Newfoundland, the proportion has been as high as 50% at times. Indeed, between 1920 and 1960, 35 percent of adult male Protestant Newfoundlanders were Orangemen, as compared with just 20% in Northern Ireland and 5%–10% in Ontario in the same period.[33]

Ghana[edit]

The Orange Order in Ghana appears to have been founded by Scots-Irish missionaries some time during the 19th century. Its rituals mirror those of the Orange Order in Ulster though it does not place restrictions on membership to those who have certain Roman Catholic family members. The Orange Order in Ghana is currently being subjected to attack by charismatic churches.[34]

Military contributions[edit]

Orangemen have fought in numerous wars, including the War of 1812, the Crimean War, the Indian Mutiny and the Second Boer War. Able Seaman Bro William George Vincent Williams of LOL 92 Melbourne, was the first Australian to be killed in the war. The Institution's most notable military contribution was on the first day (1 July) of the Battle of the Somme, 1916. Many Orangemen had joined the 36th (Ulster) Division which had been formed from various Ulster regiments and had also amalgamated Lord Edward Carson's Ulster Volunteers (who were formed to oppose Home Rule for Ireland) into its ranks. But for the outbreak of World War I, Ireland had been on the brink of civil war, as Orangemen had helped to smuggle thousands of rifles from Imperial Germany (see Larne Gun Running). Several hundred Glasgow Orangemen crossed to Belfast in September 1914, to join the 36th (Ulster) Division. Roughly 5000 members of the Division were casualties on the first day of the battle. Orangemen also fought in World War II and subsequent conflicts, and many served in the Ulster Defence Regiment during the Northern Irish Troubles, particularly during the 1970s and 1980s. At least five Orangemen have been awarded the Victoria Cross: George Richardson, in the Indian Mutiny; Robert Hanna, Robert Quigg[35] and Abraham Acton during World War I; and Rev. John Weir Foote in World War II.[citation needed]

Numerous lodges have been formed by serving soldiers during various conflicts, with varying levels of official approval. In September 2007 there was controversy when a photograph of British soldiers in Iraq, wearing Orange sashes and carrying a banner reading 'Rising Sons of Basra', appeared in the Ulster Volunteer Force magazine The Purple Standard.[36]

Orange war memorials[edit]

The Institution has been prominent in commemorating Ulster's war dead, particularly Orangemen and particularly those who died in the Battle of the Somme. There are numerous parades on and around 1 July in commemoration of the Somme, although the war memorial aspect is more obvious in some parades than others. There are several memorial lodges, and a number of banners which depict the Battle of the Somme, war memorials, or other commemorative images.

In the grounds of the Ulster Tower Thiepval, which commemorates the men of the Ulster Division who died in the Battle of the Somme, a smaller monument pays homage to the Orangemen who died in the war.[37]

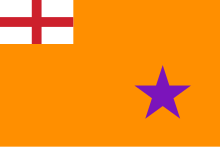

Orange Order flag[edit]

The Orange Order flag consists of an orange background, a St George's Cross in the top left corner and a purple star which was the symbol of the Williamite forces.

Notes and references[edit]

- ^ "… No catholic and no-one whose close relatives are catholic may be a member." Northern Ireland The Orange State, Michael Farrell

- ^ McGarry, John & O'Leary, Brendan (1995). Explaining Northern Ireland: Broken Images. Blackwell Publishers. pp. p. 180. ISBN 978-0631183495.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ The Orange marches

- ^ Drumcree: The Orange Order’s Last stand, Chris Ryder and Vincent Kearney, Methuen, ISBN 0 413 76260 2.

- ^ Through the Minefield, David McKittrick, Blackstaff Press, 1999, Belfast, ISBN 0 85640 652 x Parameter error in {{ISBN}}: invalid character.

- ^ http://www.birw.org/Parades%202005.html

- ^ http://en.epochtimes.com/news/6-7-11/43805.html

- ^ http://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/breaking-news/ireland/article2763784.ece

- ^ "Qualifications of an Orangeman". City of Londonderry Grand Orange Lodge.

- ^ "Inside the Hidden World of Secret Societies". Evangelical Truth. (An example)

- ^ "The Orange Order". Inside the Hidden World of Secret Societies. ("On top of these previous concerns, there has been a growing evangelical opposition to the highly degrading ritualistic practices of the Royal Arch Purple and the Royal Black Institutions within the Orange over this past number of years.")

- ^ http://www.theyworkforyou.com/ni/?gid=2007-09-11.2.60 SDLP MLA Mary Bradley

- ^ http://www.newsletter.co.uk/news/Shinner-falls-off-Orange-hall.3163541.jp

- ^ http://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/news/local-national/article2539736.ece

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/northern_ireland/6904579.stm

- ^ Kaufmann, Eric (2007). The Orange Order: A Contemporary Northern Irish History. Oxford University Press.

- ^ For the Cause of Liberty, Terry Golway, Touchstone, 2000, ISBN 0 684 85556 9

- ^ Ireland Her Own, T. A. Jackson, Lawrence & Wishart, London, First published in 1947, Reprinted 1971, 1973, 1976, 1985 and 1991, ISBN 0 85315 735 9

- ^ Ireland A History, Robert Kee, Abacus, First published 1982 Revised edition published 2003, 2004 and 2005, ISBN 0 349 11676 8

- ^ Ireland History of a Nation, David Ross, Geddes & Grosset, Scotland, First published 2002, Reprinted 2005 & 2006, ISBN 10: 1 84205 164 4

- ^ Kaufmann, Eric (2007). The Orange Order: A Contemporary Northern Irish History. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Kaufmann, Eric (November 2005). "The New Unionism". Prospect.

- ^ Kaufmann, Eric (2007). The Decline of the Loyal Family: Unionism and Orangeism in Northern Ireland. Manchester University Press.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kaufmann, Eric (2007). The Orange Order: A Contemporary Northern Irish History. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Tonge, Jonathan (September 2004). "Eating the Oranges? The Democratic Unionist Party and the Orange Order Vote in Northern Ireland" (PDF). EPOP 2004 Conference, University of Oxford.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kennaway, Brian (2006). The Orange Order: A Tradition Betrayed. Methuen. ISBN 0413775356.

- ^ An Orange day out in the Republic, 9 July 2001

- ^ "The Orange Order in Ontario, Newfoundland, Scotland and Northern Ireland: A Macro-Social Analysis" (PDF). The Orange Order in Canada (Dublin: Four Courts. 2006.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Maps". Eric Kaufmann's Homepage.

- ^ Kaufmann, Eric (2006). "The Dynamics of Orangeism in Scotland: The Social Sources of Political Influence in a Large Fraternal Organization" (PDF). Eric Kaufmann's Homepage.

- ^ Walker, Graham (1992). "The Orange Order in Scotland Between the Wars". International Review of Social History. 37 (2): 177–206.

- ^ http://edinburghnews.scotsman.com/index.cfm?id=453432007

- ^ Wilson, David A. (2007). The Orange Order in Canada.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|[ editor=ignored (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "West Africa". OrangeNet.

- ^ Michael MacDonagh, Teh Irish on the Somme, London, 1917, p.48.

- ^ http://www.guardian.co.uk/military/story/0,,2165538,00.html

- ^ Steven Moore, The Irish on the Somme: A Battlefield Guide to the Irish Regiments in the Great War and the Monuments to their Memory, Belfast, 2005, p.110

Further reading[edit]

- Kaufmann, Eric (2007). The Orange Order: A Contemporary Northern Irish History. Oxford University Press.

- Gallagher, Tom (1987). Glasgow, the Uneasy Peace: Religious Tensions in Modern Scotland, 1819–1914. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0719023963.

- McFarland, Elaine (1990). Protestants First: Orangeism in Nineteenth Century Scotland. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 074860202X.

- Neal, Frank (1991). Sectarian Violence: The Liverpool Experience, 1819–1914: An Aspect of Anglo–Irish History. Manchester University Press.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|ed=ignored (help) (Considered the principal study of English Orange traditions) - Sibbert, R.M. (1939). Orangeism in Ireland and throughout the Empire. London. (Strongly favorable)

- Senior, H. (1966). Orangeism in Ireland and Britain, 1795–1836. London.

- Gray, Tony (1972). The Orange Order. The Bodley Head. London. ISBN 0370013409.

Canada and United States[edit]

- Wilson, David A. (ed.) (2007). The Orange Order in Canada. Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1-84682-077-9.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Akenson, Don (1986). The Orangeman: The Life & Ties of Ogle Gowan. Lorimer. ISBN 088862963X.

- Cadigan, Sean T. (1991). "Paternalism and Politics: Sir Francis Bond Head, the Orange Order, and the Election of 1836". Canadian Historical Review. 72 (3): 319–347.

- Currie, Philip (1995). "Toronto Orangeism and the Irish Question, 1911–1916". Ontario History. 87 (4): 397–409.

- Gordon, Michael (1993). The Orange riots: Irish political violence in New York City, 1870 and 1871. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801427541.

- Houston, Cecil J. (1980). The sash Canada wore: A historical geography of the Orange Order in Canada. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0802054935.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Pennefather, R. S. (1984). The orange and the black: Documents in the history of the Orange Order, Ontario, and the West, 1890–1940. Orange and Black Publications. ISBN 0969169108.

- See, Scott W. (1983). "The Orange Order and Social Violence in Mid-nineteenth Century Saint John". Acadiensis. 13 (1): 68–92.

- See, Scott W. (1991). "Mickeys and Demons' vs. 'Bigots and Boobies': The Woodstock Riot of 1847". Acadiensis. 21 (1): 110–131.

- See, Scott W. (1993). Riots in New Brunswick: Orange Nativism and Social Violence in the 1840s. ISBN 0802077706.

{{cite book}}: Text "University of Toronto Press" ignored (help) - Senior, Hereward (1972). Orangeism: The Canadian Phase. Toronto, New York, McGraw-Hill Ryerson. ISBN 007092998X.

- Way, Peter (1995). "The Canadian Tory Rebellion of 1849 and the Demise of Street Politics in Toronto" (PDF). British Journal of Canadian Studies. 10 (1): 10–30.

- Winder, Gordon M. "Trouble in the North End: The Geography of Social Violence in Saint John, 1840–1860". Errington and Comacchio. 1: 483–500.

External links[edit]

- Eric Kaufmann's Orange Order Page

- The Orange Order, Militant Protestantism and anti-Catholicism: A Bibliographical Essay (1999)

- Grand Orange Lodge of England

- The Grand Orange Lodge Of Ireland

- Video clip of Mohawk LOL 99 Orange Order in Belfast

- Orange Chronicle

- OrangeNet

- City of Londonderry Grand Orange Lodge

- Newbuildings Victoria LOL 1087

- Woodburn Ebenezer LOL787

- Edmonton's "Strathcona" Loyal Orange Lodge1654

- Parkmount Junior LOL150, Portadown

- Orange Order Information

de:Oranier-Orden es:Orden de Orange nl:Oranje Orde no:Oransjeordenen fi:Oranialaisveljeskunta sv:Oranienorden