User:Nerdsauce/sandbox

Go to Syllabus and browse for Articles to use. Get the Doctrines, cite them, etc. Good articles on this issue.

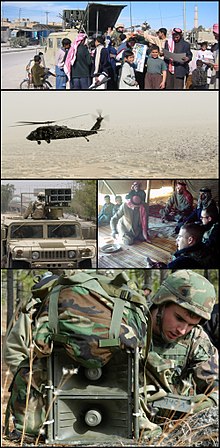

Information Operations in Global War on Terror are the application of IO activities in fighting the GWOT. By definition in Joint Publication 3-13 "IO are described as the integrated employment of electronic warfare (EW), computer network operations (CNO), psychological operations (PSYOP), military deception (MILDEC), and operations security (OPSEC), in concert with specified supporting and related capabilities, to influence, disrupt, corrupt or usurp adversarial human and automated decision making while protecting our own.[1]comes from governments and private entities of various kinds. Information Operations (IO) are ctions taken to affect adversary information and information systems while defending one's own information and information systems. or rumors deliberately spread widely to influence opinions.[2]

Information Operations[edit]

{{main|

IO is diverse, crosses all branches of the military, and utilizes techniques and tools both in the real world and cyberspace. As part of COIN strategy, it is essential in winning the hearts and minds if the US and the West are to succeed in calming victory in the GWOT. Information Operations covers a broad number of topics and has been called many things over a period of time, to include psychological warfare, psychological operations, MISO, strategic communication, etc.

Actors

United States[edit]

Department of Defense[edit]

Army

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1st_Information_Operations_Command_(Land)

- http://www.tioh.hqda.pentagon.mil/Heraldry/ArmyDUISSICOA/ArmyHeraldryUnit.aspx?u=7197

Navy

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Naval_Network_Warfare_Command

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Tenth_Fleet#U.S._Fleet_Cyber_Command

Marines

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Marine_Corps_Forces_Special_Operations_Command

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marine_Special_Operations_Regiment_(United_States)

Air Force

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/688th_Information_Operations_Wing

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_United_States_Air_Force_network_squadrons#Information_Operations_Squadrons

NSA

Special Operations[edit]

There are multiple units within the Special Operation Forces/Special Operations (SOF)/(SPECOPS) community that are tasked with information operation support. Many of these same units are tasked with other efforts simultaneously and will be used for IO when appropriate or in conjunction with other units when in theater.

- "A cheap and effective way to augment the Soldiers on the ground is to defeat radical extremist groups' ideologies and continue to win over the Iraqi population. The first step in developing this capability will be for the United States to establish a strategic framework that provides a central role for information operations (IO). These operations are analogous to a political campaign; they revolve around putting together and conveying a coherent message that convinces people to be sympathetic to one group and oppose that group's adversary. In Iraq and in the broader war against violent Jihadism, the United States not only needs the power to act, but also the power to influence how its actions are interpreted."[3]

There is a major call for better integration of IO capabilities at the special operating level because that is where the shift in DOD has occurred. More spending on Special Operations has occurred to combat insurgency and terrorists, yet there has not been a dedicated integration of IO into these tasks. IO is viewed as support operations, and there are multiple units within the SPECOPS community that have training in IO, but only as a support role and not a completely dedicated member of a team.[4]

Methods/Tactics[edit]

United States[edit]

Various methods are used for terrorists to use in their own IO campaigns. While within the United States, the main forms of IO from terrorists comes from the internet in the forms of audio and video. These communications/propaganda are designed specifically for the population and decision makers of the United States and US allies.

“Or as one jihadi magazine found on Irhabi007’s computer (an infamous webmaster for Zarqawi until his eventual capture in London) explained: “Film everything; this is good advice for all mujahideen [holy warriors]. Brothers, don’t disdain photography. You should be aware that every fram you take is as good as a missle fired at the Crusader enemy and his puppets.”[5]

Another tool is citizen journalism which is picked up by the major media networks. This work usually consists of low-quality video footage, and while published to the web, is usually picked up and aired as fast as possible to achieve higher ratings.[6]

- Embeded Jouranlists - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Embedded_journalism

- Leaflets - http://www.psywar.org/

- radio - Radio in a Box, Voice of America

- video - Online stuff like - http://www.liveleak.com/view?i=4eb_1330907622 - Also official statements etc.

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Counter-insurgency#Public_diplomacy

Electronic Warfare[edit]

Many of the EW capabilities used in the GWOT consist with aerial systems. The capabilities of these aircraft allow for a mobile command and control center to coordinate IO activities from above. The use of cell-phones by terrorists or insurgents can be tracked using these platforms for further action. As well, the jamming of cell-phone or radio communication can be coordinated in the when coalition or US forces are in a specific area of operation.

Platforms[edit]

---The EA-6B Prowler (Figure 22) is airborne jamming system. In combat operations the Prowler accompanies strike aircraft to their target. In addition to its jamming capabilities it also as the High Speed Anti-Radiation Missile (HARM) to destroy the radars of ADA systems that target the aircraft. The Air Force, Marines, and Navy all fly this aircraft. Every aircraft carrier includes at least one squadron of Prowlers (4 aircraft) in its compliment of aircraft. During major combat operations it supported strikes against combat forces. Today it serves as part of TF IED.[7]

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/F-16_Fighting_Falcon_variants#F-16CJ.2FDJ_Block_50D.2F52D

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/EA-18_Growler

CNO[edit]

Suter[edit]

Suter is a military computer program developed by BAE Systems that attacks computer networks and communications systems belonging to an enemy. Development of the program has been managed by Big Safari, a secret unit of the United States Air Force. It is specialised to interfere with the computers of integrated air defence systems.[8][dead link] Suter was integrated into US unmanned aircraft by L-3 Communications.[9]

Three generations of Suter have been developed. Suter 1 allows its operators to monitor what enemy radar operators can see. Suter 2 lets them take control of the enemy's networks and direct their sensors. Suter 3, tested in summer 2006, enables the invasion of links to time-critical targets such as battlefield ballistic missile launchers or mobile surface-to-air missile launchers.

The program has been tested with aircraft such as the EC-130, RC-135, and F-16CJ.[8] It has been used in Iraq and Afghanistan since 2006.[10][11]

U.S. Air Force officials have speculated that a technology similar to Suter was used by the Israeli Air Force to thwart Syrian radars and sneak into their airspace undetected in Operation Orchard on September 6, 2007. The evasion of air defence radar was otherwise unlikely because the F-15s and F-16s used by the IAF were not equipped with stealth technology.[10][12]

PSYOP[edit]

"The bombing of Afghanistan began on October 7. Along with the bombing, the United States Air Force also dropped food packets for the Afghan refugees. Aerial propaganda leaflets were not dropped the first week due to high winds. The first leaflet drop took place on October 15, coordinated with Coalition radio broadcasts. EC-130-E Command Solo aircraft from the 193rd Special Operations Wing flying out of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, broadcast to the Afghan people. The modified C-130 can broadcast radio or TV signals - AM, FM and HF. It broadcasts across the band from 45 kilohertz to 1000 megahertz."[16]

EC-130[edit]

The EC-130E Airborne Battlefield Command and Control Center (ABCCC) was based on a basic C-130E platform and provided tactical airborne command post capabilities to air commanders and ground commanders in low air threat envionments. This EC-130E ABCCC has since been retired.

The EC-130E Commando Solo was an earlier version of a U.S. Air Force and Air National Guard psychological operations (PSYOPS) aircraft. This aircraft also employed a C-130E airframe, but was modified by using the mission electronic equipment from the retired EC-121S Coronet Solo aircraft. This airframe served during the first Gulf War (Operation Desert Storm), the second Gulf War (Operation Iraqi Freedom) and in Operation Enduring Freedom. The EC-130E was eventually replaced by the EC-130J Commando Solo and was retired in 2006.

The EC-130J Commando Solo is a modified C-130J Hercules used to conduct psychological operations (PSYOP) and civil affairs broadcast missions in the standard AM, FM, HF, TV and military communications bands. Missions are flown at the maximum altitudes possible to ensure optimum propagation patterns. The EC-130J flies during either day or night scenarios with equal success, and is air-refuelable. A typical mission consists of a single-ship orbit which is offset from the desired target audience. The targets may be either military or civilian personnel. The Commando Solo is operated exclusively by the Air National Guard, specifically the 193d Special Operations Wing (193 SOW), a unit of the Pennsylvania Air National Guard operationally gained by the Air Force Special Operations Command (AFSOC). The 193 AOW is based at the Harrisburg Air National Guard Base (former Olmstead AFB) at Harrisburg International Airport in Middletown, Pennsylvania.

The U.S. Navy's EC-130Q Hercules TACAMO ("Take Charge and Move Out") aircraft was a land-based naval aviation platform that served as a SIOP strategic communications link aircraft for the U.S. Navy's Fleet Ballistic Missile (FBM) submarine force and as a backup communications link for the USAF manned strategic bomber and intercontinental ballistic missile forces. To ensure survivability, TACAMO operated as a solo platform, well away from and not interacting with other major naval forces such as sea-based aircraft carrier strike groups and their carrier air wings or land-based maritime patrol aircraft Operated by Fleet Air Reconnaissance Squadron THREE (VQ-3) and Fleet Air Reconnaissance Squadron FOUR (VQ-4), the EC-130Q was eventually replaced by the U.S. Navy's current TACAMO platform, the Boeing 707-based E-6 Mercury.

B (SOMS-B)[edit]

- Special Operation Media Systems - B (SOMS-B)

--The SOMS-B (Figure 16) is a ground-based HMMWV mounted radio and television broadcast system. Like the EC-130C/J it can broadcast on AM, FM, SW and VHF television frequencies. The SOMS-B also has the capability to produce programming or radio and television broadcasts[17][18]

Leaflets[edit]

Radio[edit]

Radio Free Afghanistan[edit]

Radio Free Afghanistan (RFA) is the Afghan branch of Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty’s (RFE/RL) broadcast services. It broadcasts 12 hours daily as part of a 24 hour stream of programming in conjunction with Voice of America (VOA). RFA first aired in Afghanistan from 1985 to 1993 and was re-launched in January 2002. RFA produces a variety of cultural, political, and informational programs that are transmitted to listeners via shortwave, satellite and AM and FM signals provided by the International Broadcasting Bureau. RFA’s mission is "to promote and sustain democratic values and institutions in Afghanistan by disseminating news, factual information and ideas".[19]

Radio in a Box[edit]

Radio is the dominant information tool to reach wide audiences in isolated, mountainous regions. The US military has deployed RIABs throughout Afghanistan in order to communicate with the residents. Due to a 70 percent illiteracy rate and lack of education in Afghanistan radio is a vital communications tool used to broadcast information where radio ownership exceeds 80 percent.[20][21] The United States military operates approximately 100 RIABs and hire local Afghan DJs in Afghanistan to broadcast information and host call-in shows.[22][23] The United States Army employed RIAB systems to broadcast anti-Taliban and anti-Al Qaeda messages and countered Taliban propaganda by pushing onto Taliban frequencies in Paktia Province.[24][25] One advantage of employing RIAB systems is the ability to broadcast vital information immediately to a large audience in the event of a crisis.[23] One Afghan DJ has 50,000 listeners.[22] Nawa District Governor Abdul Manaf uses the local RIAB station to conduct weekly call-in shows and believes the RIAB system is one of his best communication tools to inform a large audience.[26] In Afghanistan's Paktika province, which has a literacy rate of two percent, an estimated 92 percent of the residents listen to the radio every day.[22][25] Radio programs transmitted using RIAB systems provide beneficial information to Afghan farmers in remote areas.[20] In the isolated, mountainous Wazi Kwah district of Paktika Province, a RIAB system supplies the only source of outside news.[27] Afghan National Army commanders use the RIAB to communicate to villagers and elders and provide thoughts to the community.[28] Afghans trust messages from the United States military that explain important information such as what to do when a military convoy approaches and agriculture programs. For general news, Afghans prefer other outlets of information such as the BBC or VOA because RIAB systems are controlled by the US military.[29] Special Operations first employed RIAB systems in Afghanistan in 2005 which improved their ability to supply information to and communicate with the local population in their areas of operation.[30]

Television[edit]

MILDEC[edit]

OPSEC[edit]

- NSA

Websites[edit]

secret prisons[edit]

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_site

- http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/11/01/AR2005110101644.html

- http://www.wbj.pl/article-54800-polish-officials-may-face-charges-over-secret-cia-prisons.html

violence[edit]

- Death of Osama bin Laden

- Targeted Killing

- Torture and the United States

- Torture and murder in Iraq

- Jihad

Wikileaks[edit]

-http://wikileaks.ch/ -http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikileaks

Quran Burning/Intelligence[edit]

- http://www.thenews.com.pk/article-37212-Fallout-from-Afghan-Quran-burning-widens

- http://www.theusreport.com/the-us-report/2012/2/28/koran-burning-apologies-are-ineffective-and-counter-producti.html

- http://monadee.wordpress.com/2012/03/01/hypocrisies-and-opportunisms-in-quran-burning-riots-in-afghanistan/

- http://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Military/2012/0222/Quran-burning-Were-prisoners-hiding-extremist-messages-in-books

Terrorists[edit]

"Terrorists are adept at integrating their physical acts of violence with IO. They make audio and video recordings of the incidents for distribution over the internet and on television. Their violence becomes theater, staged for its psychological impact, and replayed over and over again in the media as IO."[31]

- "Terrorists employ all the IO capabilities of U.S. military doctrine, including the five core capabilities of PSYOP, military deception, EW, CNO, and OPSEC, and the supporting and related capabilities. They use IO to support both offensive operations (acts of terrorism) and defensive operations (e.g., protecting their hiding places). They use IO strategically in support of broad objectives. While terrorists do not speak and write of “IO,” they demonstrate an understanding of the value and methods of IO capabilities. Terrorists appear to be particularly adept at PSYOP, PA, counterpropaganda, and certain forms of OPSEC and deception, driven by their desire to simultaneously reach desired audiences and hide from their enemies. They recognize the value of various media, including the Internet, and exploit it to support their cause. Terrorists and their supporters have a CNO capability, with CNA manifesting itself as “electronic jihad” rather than as acts of terror."[32]

Computer Network Operations[edit]

- CNO is comprised of 3 major themes. Attack, Exploitation, and Defense (CNA, CNE, and CND respectively). There are many examples in this area.

There are many examples of CNA and are generally done in support of other operations. Terrorists have integrated cyber attacks into their thinking, strategies, and operations as an extremely cost effective way to harm the US and other adversaries.[33]

The same can be said for CNE, which is about penetrating computer networks before actually attacking them. Gaining access to specific networks is seen to be as part of the CNA process for terrorists (they do not distinguish between the two).[34]

As for CND, terrorists are aware of keeping data secure and websites running because they use the internet. Hamas and Hizballaha have had to defend their websites from Israeli hackers who in the past have defaced them. The methods they use include access controls, encryption, authentication, firewalls, intrusion detection, anti-viral tools, audits, security management, and security awareness and training.[35]

Steganography[edit]

Military Deception[edit]

During a search of an al-Qaeda member's home, police in the U.K. uncovered what is now called "The al-Qaeda Training Manual", that instructs its members on various forms of deception, including forgeries, "blending in", hiding places, etc. including the use of covers to blend into the terrorist area of operation (usually cities with large civilian populations).[36] Most of the MILDEC terrorists use focuses on concealing activities rather than leading adversaries down a false path.[37]

PSYOP[edit]

Terrorist PSYOP differs from American PSYOP in one two major areas. First, US PSYOP targets foreign adversaries and information is coordinated with many other agencies and screened before it is published. Second, while PSYOP by US and coalition forces is "designed to bring an end to violence and save lives, terrorist PSYOP is frequently directed toward promoting violence and threatening civilian populations with death and destruction. Suicide bombers are portrayed as martyrs rather than killers of innocent people."[38]

The Internet is the main resource to spread propaganda with al-Aqaeda and other terrorist groups. "According to Bruce Hoffman, before it was taken down, al-Qaeda's website Alneda.com emphasized three themes: 1)the West is implacably hostile to Islam, 2) the only way to address this threat and the only language the West understands is the logic of violence, and 3) jihad is the only option"[39][40]

Terrorists also like to use the internet to recruit and pursuade children to their cause. As Dorothy Denning has found, "Children are being taught to hate Jews and Westerners, and to take up arms against them [through cartoons and comic-book style web pages, bedtime stories, and computer games]".[41]

OPSEC[edit]

OPSEC as an IO Core Capability. OPSEC denies the adversary the information needed to correctly assess friendly capabilities and intentions. In particular, OPSEC complements MILDEC by denying an adversary information required to both assess a real plan and to disprove a deception plan. For those IO capabilities that exploit new opportunities and vulnerabilities, such as EW and CNO, OPSEC is essential to ensure friendly capabilities are not compromised. The process of identifying essential elements of friendly information and taking measures to mask them from disclosure to adversaries is only one part of a defense-in-depth approach to securing friendly information. To be effective, other types of security must complement OPSEC. Examples of other types of security include physical security, IA programs, computer network defense (CND), and personnel programs that screen personnel and limit authorized access. Operations security is the process of identifying essential elements of friendly information and subsequently analyzing friendly actions attendant to military operations and other activities to identify those actions that can be observed by adversary intelligence systems, determine indicators hostile intelligence systems might obtain that could be interpreted or pieced together to derive essential elements of friendly information time to be useful to adversaries, and select and execute measures that eliminate or reduce to an acceptable level the vulnerabilities of friendly actions to adversary exploitation.[42]

All terrorists practice a high level of OPSEC since their need to be secret is how they can be successful. Whether it is the al-Qaeda training manual, online magazines targeted for the world, or the training of youth in Jihad camps, OPSEC is one of the first priorities for terrorists.[43]

Secure communications are big as well. The September 11 hijackers, for example, accessed anonymous Hotmail and Yahoo! accounts from computers at Kinko's and at a public library.[44] Messages are also coded. Three weeks before the attacks, Mohammad Atta reportedly received a coded email message that read: "The semester begins in three more weeks. We've obtained 19 confirmations for studies in the faculty of law, the faculty of urban planning, the faculty of fine arts, and the faculty of engineering."[45] The faculties referred to the four targets (twin towers, Pentagon, and Capitol)[46]

The list of methods goes on and on and is very similar to the methods used in organized crime around the world.

Criticism[edit]

- “In [stability, reconstruction, and COIN operations], the most important targets of influence are not enemy commanders, but individuals and groups, both local and international, whose cooperation is vital to the mission’s success. Granted, joint and Army IO doctrine publications do not ignore these targets – PSYOP and counterpropaganda can be designed to influence them. But it is notable that the activities most directly aimed at influencing local and international audiences – functions such as public affairs, civil affairs, CMOs, and defense support to public diplomacy – are treated only as ‘related activities’ in IO doctrine, if they are mentioned at all” [47]

- "There must be a fundamental change of culture in how ISAF approaches operations. StratCom should not be a separate Line of Operation, but rather an integral and fully embedded part of policy development, planning processes, and the execution of operations. Analyzing and maximizing StratCom effects must be central to the formulation of schemes of maneuver and during the execution of operations. In order to affect this paradigm shift, ISAF HQ must synchronize all stratCom stakeholders. Implicit in this change of culture is the clear recognition that modern strategic communication is about credible dialogue, not a monologue where we design our systems and resources to deliver messages to target audiences in the most effective manner. This is now a population centric campaign and no effort should be spared to ensure that the Afghan people are part of the conversation. Receiving, understanding, and amending behavior as a result of messages received from audiences can be an effective method of gaining genuine trust and credibility. This would improve the likelihood of the population accepting ISAF messages and changing their behavior as a result."[48]

See Also[edit]

- Information Operations Roadmap (DOD 2003)

- Information Operations (JP 3-13 2006)

- Operations Security (JP 3-13.3)

- Military Deception (JP 3-13.4)

- Joint Doctrine for PSYOPS (JP 3-53 2003)

- Joint Doctrine for Public Affairs (JP 3-61 2005)

- Destabilizing Terrorist Networks: Disrupting and Manipulating Information Flows in the Global War on Terrorism, Yale Information Society Project Conference Paper (2005).

- Seeking Symmetry in Fourth Generation Warfare: Information Operations in the War of Ideas, Presentation (PDF slides) to the Bantle - Institute for National Security and Counterterrorism (INSCT) Symposium, Syracuse University (2006).

- K. A. Taipale, Seeking Symmetry on the Information Front: Confronting Global Jihad on the Internet, 16 National Strategy F. Rev. 14 (Summer 2007).

- White House FAQ about the WoT

- CIA and the WoT

- U.S. National Military Strategic Plan for the WoT

- [1]

References[edit]

- ^ "Joint Publication 3-13: Information Operations" (PDF). United States Department of Defense. Retrieved 4/17/2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ http://www.fas.org/irp/doddir/dod/jp3_13.pdf

- ^ http://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/improving-information-operations-in-iraq-and-the-global-war-on-terror

- ^ Bloom, Lt.Col. Bradley (2004). "Information Operations in Support of Special Operations". Military Review: 45.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Internet Jihad: A World Wide Web of Terror". The Economist. The Economist. 12. Retrieved 4/17/2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=,|date=, and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Daube, Cori (2009). Youtube War: Fighting in a World of Cameras in Every Cell Phone and Photoshop on Every Computer. Carlisle: Strategic Studies Institute, p. 48

- ^ Global Security Website, Available from http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/systems/aircraft/ea-6.htm; Internet.

- ^ a b David A. Fulghum, Michael A. Dornheim, and William B. Scott. "Black Surprises". Aviation Week and Space Technology. Retrieved 2007-10-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ John Leyden (October 4, 2007). "Israel suspected of 'hacking' Syrian air defences". The Register. Retrieved 2007-10-05.

- ^ a b David A. Fulghum (October 3, 2007). "Why Syria's Air Defenses Failed to Detect Israelis". Aviation Week and Space Technology. Retrieved 2007-10-05.

- ^ David A. Fulghum (January 14, 2007). "Technology Will Be Key to Iraq Buildup". Aviation Week and Space Technology.

- ^ John Leyden (October 4, 2007). "Israel suspected of 'hacking' Syrian air defences". The Register. Retrieved 2007-10-05.

- ^ [• http://www.airforce-technology.com/features/feature1625/ • http://www.airforce-technology.com/features/feature1625/].

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help); Missing or empty|title=(help); horizontal tab character in|url=at position 2 (help) - ^ [• http://www.airforce-technology.com/features/feature1669/ • http://www.airforce-technology.com/features/feature1669/].

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help); Missing or empty|title=(help); horizontal tab character in|url=at position 2 (help) - ^ http://www.1913intel.com/2007/10/05/what-is-suter/.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Friedman, Herbert A. "Psychological Operations in Afghanistan". Retrieved 4/18/2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ DOCUMENT CALLED IO IN OEF AND IF -saved in your folder

- ^ "SOMS-B 2 MRBS Antenna System". Federal Business Opportunities. Retrieved 4/18/2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ http://www.rferl.org/section/Afghanistan/149.html/

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

The Worldwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Radio in a Box (2011). Radio in a Box "Retrieved 2011-14-10"

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

Kevin Sieffwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Radio in a Box - Giving Afghanistans Their Own Voice! (2010). Radio in a Box - Giving Afghanistans Their Own Voice! "Retrieved 2011-14-10"

- ^ Army radio connects with Afghans (2009). Army radio connects with Afghans "Retrieved 2011-10-30"

- ^ a b Military Embraces Counterinsurgency in Afghanistan (2008). Radio in a Box - Military Embraces Counterinsurgency in Afghanistan "Retrieved 2011-11-11"

- ^ /The Busiest Man in Nawa (2011). The Busiest Man in Nawa "U.S. Marine Corps Releases", "Retrieved 2011-11-10"

- ^ Local DJ celebrity to his Afghan listeners (2010). Local DJ celebrity to his Afghan listeners "Retrieved 2011-10-14"

- ^ Radio-in-a-Box: Afghanistan's New Warrior-DJs (2011). Radio-in-a-Box: Afghanistan's New Warrior-DJs "Retrieved 2011-10-14"

- ^ The Pentagon, Information Operations, and International Media Development (2010). The Pentagon, Information Operations, and International Media Development "A Report tothe Center for International Media Assistance", :e27 "Retrieved 2011-10-14"

- ^ Breaking the Afghan Insurgency (2007). Breaking the Afghan Insurgency "Special Warfare" 20 (5):e26 "Retrieved 2011-11-10"

- ^ Dorothy p. 6

- ^ Dorothy p. 20

- ^ Dorothy p. 11

- ^ Dorothy p. 11

- ^ Dorothy p. 11

- ^ http://www.justice.gov/ag/manualpart1_1.pdf

- ^ Denning, p. 7

- ^ Denning, Dorothy E. (18). "Information Operations and Terrorism". Retrieved 4/18/2012.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=,|date=, and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ ibid

- ^ Bruce Hoffman, “Al Qaeda, Trends in Terrorism, and Future Potentialities: An Assessment,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 26:429-442, 2003.

- ^ Denning, p. 5

- ^ JP-3-13 p. II-3

- ^ Dorothy p. 12

- ^ Brian Ross, “A Secret Language,” ABCNEWS.com, October 4, 2001.

- ^ 58 “Virtual Soldiers in a Holy War,” Ha’aretz Daily, September 16, 2002.

- ^ Dorothy p. 13

- ^ Baker, Ralph (2006). The Decisive Weapon: A Brigade Combat Team Commander's Perspective on Information Operations. Military Review. pp. 34–35.

- ^ McChrystal, Gen. Stanley A. (September 21). "COMISAF Initial Assessment". US Department of Defense. Retrieved 4/17/2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=,|date=, and|year=/|date=mismatch (help)