User:SalFromOuterSpace/sandbox

Default mode network[edit]

| Default mode network | |

|---|---|

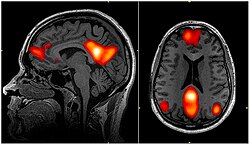

fMRI scan showing regions of the default mode network; the dorsal medial prefrontal cortex, the posterior cingulate cortex, the precuneus and the angular gyrus | |

| Anatomical terminology |

In neuroscience, the default mode network (DMN), also known as the default network, default state network, or anatomically the medial frontoparietal network (M-FPN), is a large-scale brain network primarily composed of the dorsal medial prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, precuneus and angular gyrus. It is best known for being active when a person is not focused on the outside world and the brain is at wakeful rest, such as during daydreaming and mind-wandering. It can also be active during detailed thoughts related to external task performance.[3] Other times that the DMN is active include when the individual is thinking about others, thinking about themselves, remembering the past, and planning for the future.[4][5]

The DMN was originally noticed to be deactivated in certain goal-oriented tasks and was sometimes referred to as the task-negative network,[6] in contrast with the task-positive network. This nomenclature is now widely considered misleading, because the network can be active in internal goal-oriented and conceptual cognitive tasks.[7][8][9][10] The DMN has been shown to be negatively correlated with other networks in the brain such as attention networks.[11]

Evidence has pointed to disruptions in the DMN of people with Alzheimer's disease and autism spectrum disorder.[4]

History[edit]

Hans Berger, the inventor of the electroencephalogram, was the first to propose the idea that the brain is constantly busy. In a series of papers published in 1929, he showed that the electrical oscillations detected by his device do not cease even when the subject is at rest. However, his ideas were not taken seriously, and a general perception formed among neurologists that only when a focused activity is performed does the brain (or a part of the brain) become active.[12]

But in the 1950s, Louis Sokoloff and his colleagues noticed that metabolism in the brain stayed the same when a person went from a resting state to performing effortful math problems, suggesting active metabolism in the brain must also be happening during rest.[4] In the 1970s, David H. Ingvar and colleagues observed blood flow in the front part of the brain became the highest when a person is at rest.[4] Around the same time, intrinsic oscillatory behavior in vertebrate neurons was observed in cerebellar Purkinje cells, inferior olivary nucleus and thalamus.[13]

In the 1990s, with the advent of positron emission tomography (PET) scans, researchers began to notice that when a person is involved in perception, language, and attention tasks, the same brain areas become less active compared to passive rest, and labeled these areas as becoming "deactivated".[4]

In 1995, Bharat Biswal, a graduate student at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, discovered that the human sensorimotor system displayed "resting-state connectivity," exhibiting synchronicity in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans while not engaged in any task.[14][15]

Later, experiments by neurologist Marcus E. Raichle's lab at Washington University School of Medicine and other groups[16] showed that the brain's energy consumption is increased by less than 5% of its baseline energy consumption while performing a focused mental task. These experiments showed that the brain is constantly active with a high level of activity even when the person is not engaged in focused mental work. Research thereafter focused on finding the regions responsible for this constant background activity level.[12]

Raichle coined the term "default mode" in 2001 to describe resting state brain function;[17] the concept rapidly became a central theme in neuroscience.[18] Around this time the idea was developed that this network of brain areas is involved in internally directed thoughts and is suspended during specific goal-directed behaviors. In 2003, Greicius and colleagues examined resting state fMRI scans and looked at how correlated different sections in the brain are to each other. Their correlation maps highlighted the same areas already identified by the other researchers.[19] This was important because it demonstrated a convergence of methods all leading to the same areas being involved in the DMN. Since then other networks have been identified, such as visual, auditory, and attention networks. Some of them are often anti-correlated with the default mode network.[11]

Until the mid-2000s, researchers labeled the default mode network as the "task-negative network" because it was deactivated when participants had to perform external goal-directed tasks.[6] DMN was thought to only be active during passive rest and inactive during tasks. However, more recent studies have demonstrated the DMN to be active in certain internal goal-directed tasks such as social working memory and autobiographical tasks.[7]

Around 2007, the number of papers referencing the default mode network skyrocketed.[20] In all years prior to 2007, there were 12 papers published that referenced "default mode network" or "default network" in the title; however, between 2007 and 2014 the number increased to 1,384 papers. One reason for the increase in papers was the robust effect of finding the DMN with resting-state scans and independent component analysis (ICA).[16][21] Another reason was that the DMN could be measured with short and effortless resting-state scans, meaning they could be performed on any population including young children, clinical populations, and nonhuman primates.[4] A third reason was that the role of the DMN had been expanded to more than just a passive brain network.[4]

Anatomy[edit]

This article needs attention from an expert in neuroscience or anatomy. See the talk page for details. (February 2023) |

The default mode network is an interconnected and anatomically defined[4] set of brain regions. The network can be separated into hubs and subsections:

Functional hubs:[23] Information regarding the self

- Posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) & precuneus: Combines bottom-up (not controlled) attention with information from memory and perception. The ventral (lower) part of PCC activates in all tasks which involve the DMN including those related to the self, related to others, remembering the past, thinking about the future, and processing concepts plus spatial navigation. The dorsal (upper) part of PCC involves involuntary awareness and arousal. The precuneus is involved in visual, sensorimotor, and attentional information.

- Medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC): Decisions about self-processing such as personal information, autobiographical memories, future goals and events, and decision making regarding those personally very close such as family. The ventral (lower) part is involved in positive emotional information and internally valued reward.

- Angular gyrus: Connects perception, attention, spatial cognition, and action and helps with parts of recall of episodic memories.

Dorsal medial subsystem:[23] Thinking about others

- Functional hubs: PCC, mPFC, and angular gyrus

- Dorsal medial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC): Involved in social directed thought such as determining or inferring the purpose of others' actions

- Temporoparietal junction (TPJ): Reflects on beliefs about others, also known as theory of mind

- Lateral temporal cortex: Retrieval of social semantic and conceptual knowledge

- Anterior temporal pole: Abstract conceptual information particularly social in nature

Medial temporal subsystem:[23] Autobiographical memory and future simulations

- Functional hubs: PCC, mPFC, and angular gyrus

- Hippocampus (HF+): Formation of new memories as well as remembering the past and imagining the future

- Parahippocampus (PHC): Spatial and scene recognition and simulation

- Retrosplenial cortex (RSC): Spatial navigation[24]

- Posterior inferior parietal lobe (pIPL): Junction of auditory, visual, and somatosensory information and attention

The default mode network is most commonly defined with resting state data by putting a seed in the posterior cingulate cortex and examining which other brain areas most correlate with this area.[19] The DMN can also be defined by the areas deactivated during external directed tasks compared to rest.[17] Independent component analysis (ICA) robustly finds the DMN for individuals and across groups, and has become the standard tool for mapping the default network.[16][21]

It has been shown that the default mode network exhibits the highest overlap in its structural and functional connectivity, which suggests that the structural architecture of the brain may be built in such a way that this particular network is activated by default.[1] Recent evidence from a population brain-imaging study of 10,000 UK Biobank participants further suggests that each DMN node can be decomposed into subregions with complementary structural and functional properties. It has been a widespread practice in DMN research to treat its constituent nodes to be functionally homogeneous, but the distinction between subnodes within each major DMN node has mostly been neglected. However, the close proximity of subnodes that propagate hippocampal space-time outputs and subnodes that describe the global network architecture may enable default functions, such as autobiographical recall or internally-orientated thinking.[25]

In the infant's brain, there is limited evidence of the default network, but default network connectivity is more consistent in children aged 9–12 years, suggesting that the default network undergoes developmental change.[11]

Functional connectivity analysis in monkeys shows a similar network of regions to the default mode network seen in humans.[4] The PCC is also a key hub in monkeys; however, the mPFC is smaller and less well connected to other brain regions, largely because human's mPFC is much larger and well developed.[4]

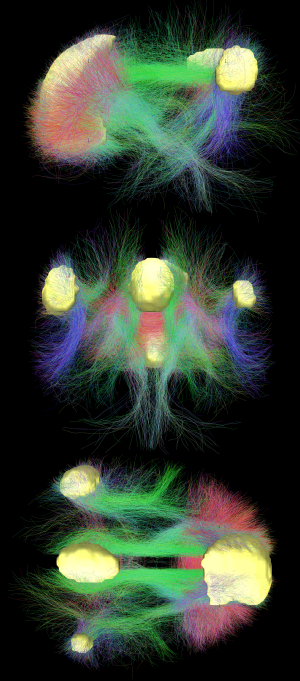

Diffusion MRI imaging shows white matter tracts connecting different areas of the DMN together.[20] The structural connections found from diffusion MRI imaging and the functional correlations from resting state fMRI show the highest level of overlap and agreement within the DMN areas.[1] This provides evidence that neurons in the DMN regions are linked to each other through large tracts of axons and this causes activity in these areas to be correlated with one another. From the point of view of effective connectivity, many studies have attempted to shed some light using dynamic causal modeling, with inconsistent results. However, directionality from the medial prefrontal cortex towards the posterior cingulate gyrus seems confirmed in multiple studies, and the inconsistent results appear to be related to small sample size analysis.[26]

Function[edit]

The default mode network is thought to be involved in several different functions:

It is potentially the neurological basis for the self:[20]

- Autobiographical information: Memories of collection of events and facts about one's self

- Self-reference: Referring to traits and descriptions of one's self

- Emotion of one's self: Reflecting about one's own emotional state

Thinking about others:[20]

- Theory of mind: Thinking about the thoughts of others and what they might or might not know

- Emotions of others: Understanding the emotions of other people and empathizing with their feelings

- Moral reasoning: Determining a just and an unjust result of an action

- Social evaluations: Good-bad attitude judgements about social concepts

- Social categories: Reflecting on important social characteristics and status of a group

- Social isolation: A perceived lack of social interaction[27]

Remembering the past and thinking about the future:[20]

- Remembering the past: Recalling events that happened in the past

- Imagining the future: Envisioning events that might happen in the future

- Episodic memory: Detailed memory related to specific events in time

- Story comprehension: Understanding and remembering a narrative

- Replay: Consolidating recently acquired memory traces[28]

The default mode network is active during passive rest and mind-wandering[4] which usually involves thinking about others, thinking about one's self, remembering the past, and envisioning the future rather than the task being performed.[20] Recent work, however, has challenged a specific mapping between the default mode network and mind-wandering, given that the system is important in maintaining detailed representations of task information during working memory encoding.[29] Electrocorticography studies (which involve placing electrodes on the surface of a subject's cerebral cortex) have shown the default mode network becomes activated within a fraction of a second after participants finish a task.[30] Additionally, during attention demanding tasks, sufficient deactivation of the default mode network at the time of memory encoding has been shown to result in more successful long-term memory consolidation.[31]

Studies have shown that when people watch a movie,[32] listen to a story,[33][34] or read a story,[35] their DMNs are highly correlated with each other. DMNs are not correlated if the stories are scrambled or are in a language the person does not understand, suggesting that the network is highly involved in the comprehension and the subsequent memory formation of that story.[34] The DMN is shown to even be correlated if the same story is presented to different people in different languages,[36] further suggesting the DMN is truly involved in the comprehension aspect of the story and not the auditory or language aspect.

The default mode network is deactivated during some external goal-oriented tasks such as visual attention or cognitive working memory tasks.[6] However, with internal goal-oriented tasks, such as social working memory or autobiographical tasks, the DMN is positively activated with the task and correlates with other networks such as the network involved in executive function.[7] Regions of the DMN are also activated during cognitively demanding tasks that require higher-order conceptual representations.[9] The DMN shows higher activation when behavioral responses are stable, and this activation is independent of self-reported mind wandering.[37]

Tsoukalas (2017) links theory of mind to immobilization, and suggests that the default network is activated by the immobilization inherent in the testing procedure (the patient is strapped supine on a stretcher and inserted by a narrow tunnel into a massive metallic structure). This procedure creates a sense of entrapment and, not surprisingly, the most commonly reported side-effect is claustrophobia.[38]

Gabrielle et al. (2019) suggests that the DMN is related to the perception of beauty, in which the network becomes activated in a generalized way to aesthetically moving domains such as artworks, landscapes, and architecture. This would explain a deep inner feeling of pleasure related to aesthetics, interconnected with the sense of personal identity, due to the network functions related to the self.[39]

Clinical significance[edit]

The default mode network has been hypothesized to be relevant to disorders including Alzheimer's disease, autism, schizophrenia, major depressive disorder (MDD), chronic pain, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and others.[4][40] In particular, the DMN has also been reported to show overlapping yet distinct neural activity patterns across different mental health conditions, such as when directly comparing attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism.[41]

People with Alzheimer's disease show a reduction in glucose (energy use) within the areas of the default mode network.[4] These reductions start off as slight decreases in patients with mild symptoms and continue to large reductions in those with severe symptoms. Surprisingly, disruptions in the DMN begin even before individuals show signs of Alzheimer's disease.[4] Plots of the peptide amyloid-beta, which is thought to cause Alzheimer's disease, show the buildup of the peptide is within the DMN.[4] This prompted Randy Buckner and colleagues to propose the high metabolic rate from continuous activation of DMN causes more amyloid-beta peptide to accumulate in these DMN areas.[4] These amyloid-beta peptides disrupt the DMN and because the DMN is heavily involved in memory formation and retrieval, this disruption leads to the symptoms of Alzheimer's disease.

DMN is thought to be disrupted in individuals with autism spectrum disorder.[4][42] These individuals are impaired in social interaction and communication which are tasks central to this network. Studies have shown worse connections between areas of the DMN in individuals with autism, especially between the mPFC (involved in thinking about the self and others) and the PCC (the central core of the DMN).[43][44] The more severe the autism, the less connected these areas are to each other.[43][44] It is not clear if this is a cause or a result of autism, or if a third factor is causing both (confounding).

Although it is not clear whether the DMN connectivity is increased or decreased in psychotic bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, several genes correlated with altered DMN connectivity are also risk genes for mood and psychosis disorders.[45]

Rumination, one of the main symptoms of major depressive disorder, is associated with increased DMN connectivity and dominance over other networks during rest.[46][47] Such DMN hyperconnectivity has been observed in first-episode depression[48] and chronic pain.[49] Altered DMN connectivity may change the way a person perceives events and their social and moral reasoning, thus increasing their susceptibility to depressive symptoms.[50]

Lower connectivity between brain regions was found across the default network in people who have experienced long-term trauma, such as childhood abuse or neglect, and is associated with dysfunctional attachment patterns. Among people experiencing PTSD, lower activation was found in the posterior cingulate gyrus compared to controls, and severe PTSD was characterized by lower connectivity within the DMN.[40][51]

Adults and children with ADHD show reduced anticorrelation between the DMN and other brain networks.[52][53] The cause may be a lag in brain maturation.[54] More generally, competing activation between the DMN and other networks during memory encoding may result in poor long-term memory consolidation, which is a symptom of not only ADHD but also depression, anxiety, autism, and schizophrenia.[31]

Modulation[edit]

The default mode network (DMN) may be modulated by the following interventions and processes:

- Acupuncture – Deactivation of the limbic brain areas and the DMN.[55] It has been suggested that this is due to the pain response.[56]

- Antidepressants – Abnormalities in DMN connectivity are reduced following treatment with antidepressant medications in PTSD.[57]

- Attention Training Technique - Research shows that even a single session of Attention Training Technique changes functional connectivity of the DMN.[58]

- Deep brain stimulation – Alterations in brain activity with deep brain stimulation may be used to balance resting state networks.[59]

- Meditation – Structural changes in areas of the DMN such as the temporoparietal junction, posterior cingulate cortex, and precuneus have been found in meditation practitioners.[60] There is reduced activation and reduced functional connectivity of the DMN in long-term practitioners.[60] Various forms of nondirective meditation, including Transcendental Meditation[61] and Acem Meditation,[62] have been found to activate the DMN.

- Physical Activity and Exercise – Physical Activity, and more likely Aerobic Training, may alter the DMN. In addition, sports experts are showing networks differences, notably of the DMN.[63][64][65]

- Psychedelic drugs – Reduced blood flow to the PCC and mPFC was observed under the administration of psilocybin. These two areas are considered to be the main nodes of the DMN.[66] One study on the effects of LSD demonstrated that the drug desynchronizes brain activity within the DMN; the activity of the brain regions that constitute the DMN becomes less correlated.[67]

- Psychotherapy – In PTSD, the abnormalities in the default mode network normalize in individuals who respond to psychotherapy interventions.[68][57]

- Sleep deprivation – Functional connectivity between nodes of the DMN in their resting-state is usually strong, but sleep deprivation results in a decrease in connectivity within the DMN.[69] Recent studies suggest a decrease in connectivity between the DMN and the task-positive network as a result of sleep loss.[70]

- Sleeping and resting wakefulness

- Onset of sleep – Increase in connectivity between the DMN and the task-positive network.[71]

- REM sleep – Possible increase in connectivity between nodes of the DMN.[71]

- Resting wakefulness – Functional connectivity between nodes of the DMN is strong.[71]

- Stage N2 of NREM sleep – Decrease in connectivity between the posterior cingulate cortex and medial prefrontal cortex.[71]

- Stage N3 of NREM sleep – Further decrease in connectivity between the PCC and MPFC.[71]

Criticism[edit]

Some have argued the brain areas in the default mode network only show up together because of the vascular coupling of large arteries and veins in the brain near these areas, not because these areas are actually functionally connected to each other. Support for this argument comes from studies that show changing in breathing alters oxygen levels in the blood which in turn affects DMN the most.[4] These studies however do not explain why the DMN can also be identified using PET scans by measuring glucose metabolism which is independent of vascular coupling[4] and in electrocorticography studies[72] measuring electrical activity on the surface of the brain, and in MEG by measuring magnetic fields associated with electrophysiological brain activity that bypasses the hemodynamic response.[73]

The idea of a "default network" is not universally accepted.[74] In 2007 the concept of the default mode was criticized as not being useful for understanding brain function, on the grounds that a simpler hypothesis is that a resting brain actually does more processing than a brain doing certain "demanding" tasks, and that there is no special significance to the intrinsic activity of the resting brain.[75]

Nomenclature[edit]

The default mode network has also been called the language network, semantic system, or limbic network.[10] Even though the dichotomy is misleading,[7] the term task-negative network is still sometimes used to contrast it against other more externally-oriented brain networks.[53]

In 2019, Uddin et al. proposed that medial frontoparietal network (M-FPN) be used as a standard anatomical name for this network.[10]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Horn, Andreas; Ostwald, Dirk; Reisert, Marco; Blankenburg, Felix (2013). "The structural-functional connectome and the default mode network of the human brain". NeuroImage. 102: 142–151. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.09.069. PMID 24099851. S2CID 6455982.

- ^ Garrity, A.; Pearlson, G. D.; McKiernan, K.; Lloyd, D.; Kiehl, K. A.; Calhoun, V. D. (2007). "Aberrant default mode functional connectivity in schizophrenia". Am. J. Psychiatry. 164 (3): 450–457. doi:10.1176/ajp.2007.164.3.450. PMID 17329470.

- ^ Sormaz, Mladen; Murphy, Charlotte; Wang, Hao-Ting; Hymers, Mark; Karapanagiotidis, Theodoros; Poerio, Giulia; Margulies, Daniel S.; Jefferies, Elizabeth; Smallwood, Jonathan (2018). "Default mode network can support the level of detail in experience during active task states". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (37): 9318–9323. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115.9318S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1721259115. PMC 6140531. PMID 30150393.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Buckner, R. L.; Andrews-Hanna, J. R.; Schacter, D. L. (2008). "The Brain's Default Network: Anatomy, Function, and Relevance to Disease". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1124 (1): 1–38. Bibcode:2008NYASA1124....1B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.689.6903. doi:10.1196/annals.1440.011. PMID 18400922. S2CID 3167595.

- ^ Lieberman, Matthew (2 September 2016). Social. Broadway Books. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-307-88910-2.

- ^ a b c Fox, Michael D.; Snyder, Abraham Z.; Vincent, Justin L.; Corbetta, Maurizio; Van Essen, David C.; Raichle, Marcus E. (5 July 2005). "The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (27): 9673–9678. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.9673F. doi:10.1073/pnas.0504136102. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1157105. PMID 15976020.

- ^ a b c d Spreng, R. Nathan (1 January 2012). "The fallacy of a "task-negative" network". Frontiers in Psychology. 3: 145. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00145. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 3349953. PMID 22593750.

- ^ Fortenbaugh, FC; DeGutis, J; Esterman, M (May 2017). "Recent theoretical, neural, and clinical advances in sustained attention research". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1396 (1): 70–91. Bibcode:2017NYASA1396...70F. doi:10.1111/nyas.13318. PMC 5522184. PMID 28260249.

- ^ a b Murphy, C; Jefferies, E; Rueschemeyer, SA; Sormaz, M; Wang, HT; Margulies, DS; Smallwood, J (1 May 2018). "Distant from input: Evidence of regions within the default mode network supporting perceptually-decoupled and conceptually-guided cognition". NeuroImage. 171: 393–401. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.01.017. PMC 5883322. PMID 29339310.

- ^ a b c Uddin, Lucina Q.; Yeo, B. T. Thomas; Spreng, R. Nathan (1 November 2019). "Towards a Universal Taxonomy of Macro-scale Functional Human Brain Networks". Brain Topography. 32 (6): 926–942. doi:10.1007/s10548-019-00744-6. ISSN 1573-6792. PMC 7325607. PMID 31707621.

- ^ a b c Broyd, Samantha J.; Demanuele, Charmaine; Debener, Stefan; Helps, Suzannah K.; James, Christopher J.; Sonuga-Barke, Edmund J. S. (2009). "Default-mode brain dysfunction in mental disorders: A systematic review". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 33 (3): 279–96. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.09.002. PMID 18824195. S2CID 7175805.

- ^ a b Raichle, Marcus (March 2010). "The Brain's Dark Energy". Scientific American. 302 (3): 44–49. Bibcode:2010SciAm.302c..44R. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0310-44. PMID 20184182.

- ^ Llinas, R. R. (2014). "Intrinsic electrical properties of mammalian neurons and CNS function: a historical perspective". Front Cell Neurosci. 8: 320. doi:10.3389/fncel.2014.00320. PMC 4219458. PMID 25408634.

- ^ Biswal, B; Yetkin, F. Z.; Haughton, V. M.; Hyde, J. S. (1995). "Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echoplanar MRI". Magn Reson Med. 34 (4): 537–541. doi:10.1002/mrm.1910340409. PMID 8524021. S2CID 775793.

- ^ Shen, H. H. (2015). "Core Concepts: Resting State Connectivity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (46): 14115–14116. Bibcode:2015PNAS..11214115S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1518785112. PMC 4655520. PMID 26578753.

- ^ a b c Kiviniemi, Vesa J.; Kantola, Juha-Heikki; Jauhiainen, Jukka; Hyvärinen, Aapo; Tervonen, Osmo (2003). "Independent component analysis of nondeterministic fMRI signal sources". NeuroImage. 19 (2 Pt 1): 253–260. doi:10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00097-1. PMID 12814576. S2CID 17110486.

- ^ a b Raichle, M. E.; MacLeod, A. M.; Snyder, A. Z.; Powers, W. J.; Gusnard, D. A.; Shulman, G. L. (2001). "Inaugural Article: A default mode of brain function". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (2): 676–82. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98..676R. doi:10.1073/pnas.98.2.676. PMC 14647. PMID 11209064.

- ^ Raichle, Marcus E.; Snyder, Abraham Z. (2007). "A default mode of brain function: A brief history of an evolving idea". NeuroImage. 37 (4): 1083–90. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.041. PMID 17719799. S2CID 3380973.

- ^ a b Greicius, Michael D.; Krasnow, Ben; Reiss, Allan L.; Menon, Vinod (7 January 2003). "Functional connectivity in the resting brain: a network analysis of the default mode hypothesis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100 (1): 253–258. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100..253G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0135058100. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 140943. PMID 12506194.

- ^ a b c d e f Andrews-Hanna, Jessica R. (1 June 2012). "The brain's default network and its adaptive role in internal mentation". The Neuroscientist. 18 (3): 251–270. doi:10.1177/1073858411403316. ISSN 1089-4098. PMC 3553600. PMID 21677128.

- ^ a b De Luca, M; Beckmann, CF; De Stefano, N; Matthews, PM; Smith, SM (15 February 2006). "fMRI resting state networks define distinct modes of long-distance interactions in the human brain". NeuroImage. 29 (4): 1359–1367. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.08.035. PMID 16260155. S2CID 16193549.

- ^ Fair, Damien A.; Cohen, Alexander L.; Power, Jonathan D.; Dosenbach, Nico U. F.; Church, Jessica A.; Miezin, Francis M.; Schlaggar, Bradley L.; Petersen, Steven E. (2009). Sporns, Olaf (ed.). "Functional Brain Networks Develop from a 'Local to Distributed' Organization". PLOS Computational Biology. 5 (5): e1000381. Bibcode:2009PLSCB...5E0381F. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000381. PMC 2671306. PMID 19412534.

- ^ a b c Andrews-Hanna, Jessica R.; Smallwood, Jonathan; Spreng, R. Nathan (1 May 2014). "The default network and self-generated thought: component processes, dynamic control, and clinical relevance". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1316 (1): 29–52. Bibcode:2014NYASA1316...29A. doi:10.1111/nyas.12360. ISSN 1749-6632. PMC 4039623. PMID 24502540.

- ^ Roseman, Moshe; Elias, Uri; Kletenik, Isaiah; Ferguson, Michael A.; Fox, Michael D.; Horowitz, Zalman; Marshall, Gad A.; Spiers, Hugo J.; Arzy, Shahar (2023-12-13). "A neural circuit for spatial orientation derived from brain lesions". Cerebral Cortex. 34 (1): bhad486. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhad486. ISSN 1460-2199. PMC 10793567. PMID 38100330.

- ^ Kernbach, J.M.; Yeo, B.T.T.; Smallwood, J.; Margulies, D.S.; Thiebaut; de Schotten, M.; Walter, H.; Sabuncu, M.R.; Holmes, A.J.; Gramfort, A.; Varoquaux, G.; Thirion, B.; Bzdok, D. (2018). "Subspecialization within default mode nodes characterized in 10,000 UK Biobank participants". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115 (48): 12295–12300. Bibcode:2018PNAS..11512295K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1804876115. PMC 6275484. PMID 30420501.

- ^ Silchenko, Alexander N.; Hoffstaedter, Felix; Eickhoff, Simon B. (2023). "Impact of sample size and regression of tissue-specific signals on effective connectivity within the core default mode network". Human Brain Mapping.

- ^ Spreng, R.N., Dimas, E., Mwilambwe-Tshilobo, L., Dagher, A., Koellinger, P., Nave, G., Ong, A., Kernbach, J.M., Wiecki, T.V., Ge, T., Holmes, A.J., Yeo, B.T.T., Turner, G.R., Dunbar, R.I.M., Bzdok, D (2020). "The default network of the human brain is associated with perceived social isolation". Nature Communications. 11 (1). Nature Publishing Group: 6393. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.6393S. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-20039-w. PMC 7738683. PMID 33319780.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Higgins C, Liu Y, Vidaurre D, Kurth-Nelson Z, Dolan R, Behrens T, Woolrich M (March 2021). "Replay bursts in humans coincide with activation of the default mode and parietal alpha networks". Neuron. 109 (5): 882–893. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2020.12.007. PMC 7927915. PMID 33357412.

- ^ Sormaz, Mladen; Murphy, Charlotte; Wang, Hao-ting; Hymers, Mark; Karapanagiotidis, Theodoros; Poerio, Giulia; Margulies, Daniel S.; Jefferies, Elizabeth; Smallwood, Jonathan (24 August 2018). "Default mode network can support the level of detail in experience during active task states". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (37): 9318–9323. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115.9318S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1721259115. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6140531. PMID 30150393.

- ^ Dastjerdi, Mohammad; Foster, Brett L.; Nasrullah, Sharmin; Rauschecker, Andreas M.; Dougherty, Robert F.; Townsend, Jennifer D.; Chang, Catie; Greicius, Michael D.; Menon, Vinod (15 February 2011). "Differential electrophysiological response during rest, self-referential, and non-self-referential tasks in human posteromedial cortex". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (7): 3023–3028. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.3023D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1017098108. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 3041085. PMID 21282630.

- ^ a b Lefebvre, Etienne; D’Angiulli, Amedeo (2019). "Imagery-Mediated Verbal Learning Depends on Vividness–Familiarity Interactions: The Possible Role of Dualistic Resting State Network Activity Interference". Brain Sciences. 9 (6): 143. doi:10.3390/brainsci9060143. ISSN 2076-3425. PMC 6627679. PMID 31216699.

- ^ Hasson, Uri; Furman, Orit; Clark, Dav; Dudai, Yadin; Davachi, Lila (7 February 2008). "Enhanced intersubject correlations during movie viewing correlate with successful episodic encoding". Neuron. 57 (3): 452–462. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.009. ISSN 0896-6273. PMC 2789242. PMID 18255037.

- ^ Lerner, Yulia; Honey, Christopher J.; Silbert, Lauren J.; Hasson, Uri (23 February 2011). "Topographic mapping of a hierarchy of temporal receptive windows using a narrated story". The Journal of Neuroscience. 31 (8): 2906–2915. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3684-10.2011. ISSN 1529-2401. PMC 3089381. PMID 21414912.

- ^ a b Simony, Erez; Honey, Christopher J; Chen, Janice; Lositsky, Olga; Yeshurun, Yaara; Wiesel, Ami; Hasson, Uri (18 July 2016). "Dynamic reconfiguration of the default mode network during narrative comprehension". Nature Communications. 7 (1): 12141. Bibcode:2016NatCo...712141S. doi:10.1038/ncomms12141. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4960303. PMID 27424918.

- ^ Regev, Mor; Honey, Christopher J.; Simony, Erez; Hasson, Uri (2 October 2013). "Selective and invariant neural responses to spoken and written narratives". The Journal of Neuroscience. 33 (40): 15978–15988. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1580-13.2013. ISSN 1529-2401. PMC 3787506. PMID 24089502.

- ^ Honey, Christopher J.; Thompson, Christopher R.; Lerner, Yulia; Hasson, Uri (31 October 2012). "Not lost in translation: neural responses shared across languages". The Journal of Neuroscience. 32 (44): 15277–15283. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1800-12.2012. ISSN 1529-2401. PMC 3525075. PMID 23115166.

- ^ Kucyi, Aaron (2016). "Spontaneous default network activity reflects behavioral variability independent of mind-wandering". PNAS. 113 (48): 13899–13904. Bibcode:2016PNAS..11313899K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1611743113. PMC 5137714. PMID 27856733.

- ^ Tsoukalas, Ioannis (2017). "Theory of Mind: Towards an Evolutionary Theory". Evolutionary Psychological Science. 4: 38–66. doi:10.1007/s40806-017-0112-x.Pdf.

- ^ Starr, G. Gabrielle; Stahl, Jonathan L.; Belfi, Amy M.; Isik, Ayse Ilkay; Vessel, Edward A. (4 September 2019). "The default-mode network represents aesthetic appeal that generalizes across visual domains". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (38): 19155–19164. Bibcode:2019PNAS..11619155V. doi:10.1073/pnas.1902650116. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6754616. PMID 31484756.

- ^ a b Akiki, Teddy J.; Averill, Christopher L.; Wrocklage, Kristen M.; Scott, J. Cobb; Averill, Lynnette A.; Schweinsburg, Brian; Alexander-Bloch, Aaron; Martini, Brenda; Southwick, Steven M.; Krystal, John H.; Abdallah, Chadi G. (2018). "Default mode network abnormalities in posttraumatic stress disorder: A novel network-restricted topology approach". NeuroImage. 176: 489–498. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.05.005. ISSN 1053-8119. PMC 5976548. PMID 29730491.

- ^ Kernbach, Julius M.; Satterthwaite, Theodore D.; Bassett, Danielle S.; Smallwood, Jonathan; Margulies, Daniel; Krall, Sarah; Shaw, Philip; Varoquaux, Gaël; Thirion, Bertrand; Konrad, Kerstin; Bzdok, Danilo (17 July 2018). "Shared endo-phenotypes of default mode dysfunction in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder". Translational Psychiatry. 8 (1): 133. doi:10.1038/s41398-018-0179-6. PMC 6050263. PMID 30018328.

- ^ Vigneshwaran, S; Mahanand, B. S.; Suresh, S; Sundararajan, N (2017). "Identifying differences in brain activities and an accurate detection of autism spectrum disorder using resting state functional-magnetic resonance imaging: A spatial filtering approach". Medical Image Analysis. 35: 375–389. doi:10.1016/j.media.2016.08.003. PMID 27585835. S2CID 4922560.

- ^ a b Washington, Stuart D.; Gordon, Evan M.; Brar, Jasmit; Warburton, Samantha; Sawyer, Alice T.; Wolfe, Amanda; Mease-Ference, Erin R.; Girton, Laura; Hailu, Ayichew (1 April 2014). "Dysmaturation of the default mode network in autism". Human Brain Mapping. 35 (4): 1284–1296. doi:10.1002/hbm.22252. ISSN 1097-0193. PMC 3651798. PMID 23334984.

- ^ a b Yerys, Benjamin E.; Gordon, Evan M.; Abrams, Danielle N.; Satterthwaite, Theodore D.; Weinblatt, Rachel; Jankowski, Kathryn F.; Strang, John; Kenworthy, Lauren; Gaillard, William D. (1 January 2015). "Default mode network segregation and social deficits in autism spectrum disorder: Evidence from non-medicated children". NeuroImage: Clinical. 9: 223–232. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2015.07.018. PMC 4573091. PMID 26484047.

- ^ Meda, Shashwath A.; Ruaño, Gualberto; Windemuth, Andreas; O’Neil, Kasey; Berwise, Clifton; Dunn, Sabra M.; Boccaccio, Leah E.; Narayanan, Balaji; Kocherla, Mohan (13 May 2014). "Multivariate analysis reveals genetic associations of the resting default mode network in psychotic bipolar disorder and schizophrenia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (19): E2066–E2075. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111E2066M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1313093111. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4024891. PMID 24778245.

- ^ Berman, MG; Peltier, S; Nee, DE; Kross, E; Deldin, PJ; Jonides, J (October 2011). "Depression, rumination and the default network". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 6 (5): 548–55. doi:10.1093/scan/nsq080. PMC 3190207. PMID 20855296.

- ^ Hamilton, J.Paul (2011). "Default-Mode and Task-Positive Network Activity in Major Depressive Disorder: Implications for Adaptive and Maladaptive Rumination" (PDF). Biological Psychiatry. 70 (4): 327–333. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.02.003. PMC 3144981. PMID 21459364. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ Zhu, X; Wang, X; Xiao, J; Liao, J; Zhong, M; Wang, W; Yao, S (2012). "Evidence of a dissociation pattern in resting-state default mode network connectivity in first-episode, treatment-naive major depression patients". Biological Psychiatry. 71 (7): 611–7. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.10.035. PMID 22177602. S2CID 23697809.

- ^ Kucyi, A; Moayedi, M; Weissman-Fogel, I; Goldberg, M. B.; Freeman, B. V.; Tenenbaum, H. C.; Davis, K. D. (2014). "Enhanced medial prefrontal-default mode network functional connectivity in chronic pain and its association with pain rumination". Journal of Neuroscience. 34 (11): 3969–75. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5055-13.2014. PMC 6705280. PMID 24623774.

- ^ Sambataro, Fabio; Wolf, Nadine; Giusti, Pietro; Vasic, Nenad; Wolf, Robert (October 2013). "Default mode network in depression: A pathway to impaired affective cognition?" (PDF). Clinical Neuralpyschiatry. 10: 212–216. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ^ Dr. Ruth Lanius, Brain Mapping conference, London, November 2010

- ^ Hoekzema, E; Carmona, S; Ramos-Quiroga, JA; Richarte Fernández, V; Bosch, R; Soliva, JC; Rovira, M; Bulbena, A; Tobeña, A; Casas, M; Vilarroya, O (April 2014). "An independent components and functional connectivity analysis of resting state fMRI data points to neural network dysregulation in adult ADHD". Human Brain Mapping. 35 (4): 1261–72. doi:10.1002/hbm.22250. PMC 6869838. PMID 23417778.

- ^ a b Mills, BD; Miranda-Dominguez, O; Mills, KL; Earl, E; Cordova, M; Painter, J; Karalunas, SL; Nigg, JT; Fair, DA (2018). "ADHD and attentional control: Impaired segregation of task positive and task negative brain networks". Network Neuroscience. 2 (2): 200–217. doi:10.1162/netn_a_00034. PMC 6130439. PMID 30215033.

- ^ Sripada, CS; Kessler, D; Angstadt, M (30 September 2014). "Lag in maturation of the brain's intrinsic functional architecture in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (39): 14259–64. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11114259S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1407787111. PMC 4191792. PMID 25225387.

- ^ Huang, Wenjing; Pach, Daniel; Napadow, Vitaly; Park, Kyungmo; Long, Xiangyu; Neumann, Jane; Maeda, Yumi; Nierhaus, Till; Liang, Fanrong; Witt, Claudia M.; Harrison, Ben J. (9 April 2012). "Characterizing Acupuncture Stimuli Using Brain Imaging with fMRI – A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Literature". PLOS ONE. 7 (4): e32960. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...732960H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032960. PMC 3322129. PMID 22496739.

- ^ Chae, Younbyoung; Chang, Dong-Seon; Lee, Soon-Ho; Jung, Won-Mo; Lee, In-Seon; Jackson, Stephen; Kong, Jian; Lee, Hyangsook; Park, Hi-Joon; Lee, Hyejung; Wallraven, Christian (March 2013). "Inserting Needles into the Body: A Meta-Analysis of Brain Activity Associated With Acupuncture Needle Stimulation". The Journal of Pain. 14 (3): 215–222. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2012.11.011. PMID 23395475. S2CID 36594091.

- ^ a b Akiki, Teddy J.; Averill, Christopher L.; Abdallah, Chadi G. (2017). "A Network-Based Neurobiological Model of PTSD: Evidence From Structural and Functional Neuroimaging Studies". Current Psychiatry Reports. 19 (11): 81. doi:10.1007/s11920-017-0840-4. ISSN 1523-3812. PMC 5960989. PMID 28924828.

- ^ Kowalski, Joachim; Wierzba, Małgorzata; Wypych, Marek; Marchewka, Artur; Dragan, Małgorzata (1 September 2020). "Effects of attention training technique on brain function in high- and low-cognitive-attentional syndrome individuals: Regional dynamics before, during, and after a single session of ATT". Behaviour Research and Therapy. 132: 103693. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2020.103693. ISSN 0005-7967. PMID 32688045. S2CID 220669531.

- ^ Kringelbach, Morten L.; Green, Alexander L.; Aziz, Tipu Z. (2 May 2011). "Balancing the Brain: Resting State Networks and Deep Brain Stimulation". Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience. 5: 8. doi:10.3389/fnint.2011.00008. PMC 3088866. PMID 21577250.

- ^ a b Fox, Kieran C. R.; Nijeboer, Savannah; Dixon, Matthew L.; Floman, James L.; Ellamil, Melissa; Rumak, Samuel P.; Sedlmeier, Peter; Christoff, Kalina (2014). "Is meditation associated with altered brain structure? A systematic review and meta-analysis of morphometric neuroimaging in meditation practitioners". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 43: 48–73. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.03.016. PMID 24705269. S2CID 207090878.

- ^ Raffone, Antonino; Srinivasan, Narayanan (2010). "The exploration of meditation in the neuroscience of attention and consciousness". Cognitive Processing. 11 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1007/s10339-009-0354-z. PMID 20041276.

- ^ Xu, J; Vik, A; Groote, IR; Lagopoulos, J; Holen, A; Ellingsen, Ø; Håberg, AK; Davanger, S (2014). "Nondirective meditation activates default mode network and areas associated with memory retrieval and emotional processing". Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8 (86): 86. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00086. PMC 3935386. PMID 24616684.

- ^ Voss, Michelle W.; Soto, Carmen; Yoo, Seungwoo; Sodoma, Matthew; Vivar, Carmen; van Praag, Henriette (April 2019). "Exercise and Hippocampal Memory Systems". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 23 (4): 318–333. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2019.01.006. PMC 6422697. PMID 30777641.

- ^ Shao, Mengling; Lin, Huiyan; Yin, Desheng; Li, Yongjie; Wang, Yifan; Ma, Junpeng; Yin, Jianzhong; Jin, Hua (1 October 2019). Rao, Hengyi (ed.). "Learning to play badminton altered resting-state activity and functional connectivity of the cerebellar sub-regions in adults". PLOS ONE. 14 (10): e0223234. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1423234S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0223234. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6771995. PMID 31574108.

- ^ Muraskin, Jordan; Dodhia, Sonam; Lieberman, Gregory; Garcia, Javier O.; Verstynen, Timothy; Vettel, Jean M.; Sherwin, Jason; Sajda, Paul (December 2016). "Brain dynamics of post-task resting state are influenced by expertise: Insights from baseball players: Brain Dynamics of Post-Task Resting State". Human Brain Mapping. 37 (12): 4454–4471. doi:10.1002/hbm.23321. PMC 5113676. PMID 27448098.

- ^ Carhart-Harris, Robin L.; Erritzoe, David; Williams, Tim; Stone, James M.; Reed, Laurence J.; Colasanti, Alessandro; Tyacke, Robin J.; Leech, Robert; Malizia, Andrea L.; Murphy, Kevin; Hobden, Peter; Evans, John; Feilding, Amanda; Wise, Richard G.; Nutt, David J. (2012). "Neural correlates of the psychedelic state as determined by fMRI studies with psilocybin". PNAS. 109 (6): 2138–2143. doi:10.1073/pnas.1119598109. PMC 3277566. PMID 22308440.

- ^ Carhart-Harris, Robin L.; Muthukumaraswamy, Suresh; Roseman, Leor; Kaelen, Mendel; Droog, Wouter; Murphy, Kevin; Tagliazucchi, Enzo; Schenberg, Eduardo E.; Nest, Timothy; Orban, Csaba; Leech, Robert; Williams, Luke T.; Williams, Tim M.; Bolstridge, Mark; Sessa, Ben; McGonigle, John; Sereno, Martin I.; Nichols, David; Hellyer, Peter J.; Hobden, Peter; Evans, John; Singh, Krish D.; Wise, Richard G.; Curran, H. Valerie; Feilding, Amanda; Nutt, David J. (26 April 2016). "Neural correlates of the LSD experience revealed by multimodal neuroimaging". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (17): 4853–4858. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.4853C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1518377113. PMC 4855588. PMID 27071089.

- ^ Sripada, Rebecca K.; King, Anthony P.; Welsh, Robert C.; Garfinkel, Sarah N.; Wang, Xin; Sripada, Chandra S.; Liberzon, Israel (2012). "Neural Dysregulation in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder". Psychosomatic Medicine. 74 (9): 904–911. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e318273bf33. ISSN 0033-3174. PMC 3498527. PMID 23115342.

- ^ McKenna, Benjamin S.; Eyler, Lisa T. (2012). "Overlapping prefrontal systems involved in cognitive and emotional processing in euthymic bipolar disorder and following sleep deprivation: A review of functional neuroimaging studies". Clinical Psychology Review. 32 (7): 650–663. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2012.07.003. PMC 3922056. PMID 22926687.

- ^ Basner, Mathias; Rao, Hengyi; Goel, Namni; Dinges, David F (October 2013). "Sleep deprivation and neurobehavioral dynamics". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 23 (5): 854–863. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2013.02.008. PMC 3700596. PMID 23523374.

- ^ a b c d e Picchioni, Dante; Duyn, Jeff H.; Horovitz, Silvina G. (15 October 2013). "Sleep and the functional connectome". NeuroImage. 80: 387–396. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.05.067. PMC 3733088. PMID 23707592.

- ^ Foster, Brett L.; Parvizi, Josef (1 March 2012). "Resting oscillations and cross-frequency coupling in the human posteromedial cortex". NeuroImage. 60 (1): 384–391. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.12.019. ISSN 1095-9572. PMC 3596417. PMID 22227048.

- ^ Morris, Peter G.; Smith, Stephen M.; Barnes, Gareth R.; Stephenson, Mary C.; Hale, Joanne R.; Price, Darren; Luckhoo, Henry; Woolrich, Mark; Brookes, Matthew J. (4 October 2011). "Investigating the electrophysiological basis of resting state networks using magnetoencephalography". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (40): 16783–16788. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10816783B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1112685108. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3189080. PMID 21930901.

- ^ Fair, D. A.; Cohen, A. L.; Dosenbach, N. U. F.; Church, J. A.; Miezin, F. M.; Barch, D. M.; Raichle, M. E.; Petersen, S. E.; Schlaggar, B. L. (2008). "The maturing architecture of the brain's default network". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (10): 4028–32. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.4028F. doi:10.1073/pnas.0800376105. PMC 2268790. PMID 18322013.

- ^ Morcom, Alexa M.; Fletcher, Paul C. (October 2007). "Does the brain have a baseline? Why we should be resisting a rest". NeuroImage. 37 (4): 1073–1082. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.09.013. PMID 17052921. S2CID 3356303.

External links[edit]

Electrocorticography[edit]

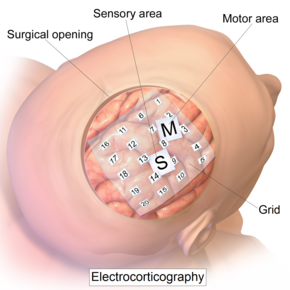

| Electrocorticography | |

|---|---|

Intracranial electrode grid for electrocorticography. | |

| Synonyms | Intracranial electroencephalography |

| Purpose | record electrical activity from the cerebral cortex.(invasive) |

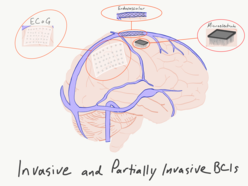

Electrocorticography (ECoG), a type of intracranial electroencephalography (iEEG), is a type of electrophysiological monitoring that uses electrodes placed directly on the exposed surface of the brain to record electrical activity from the cerebral cortex. In contrast, conventional electroencephalography (EEG) electrodes monitor this activity from outside the skull. ECoG may be performed either in the operating room during surgery (intraoperative ECoG) or outside of surgery (extraoperative ECoG). Because a craniotomy (a surgical incision into the skull) is required to implant the electrode grid, ECoG is an invasive procedure.

History[edit]

ECoG was pioneered in the early 1950s by Wilder Penfield and Herbert Jasper, neurosurgeons at the Montreal Neurological Institute.[1] The two developed ECoG as part of their groundbreaking Montreal procedure, a surgical protocol used to treat patients with severe epilepsy. The cortical potentials recorded by ECoG were used to identify epileptogenic zones – regions of the cortex that generate epileptic seizures. These zones would then be surgically removed from the cortex during resectioning, thus destroying the brain tissue where epileptic seizures had originated. Penfield and Jasper also used electrical stimulation during ECoG recordings in patients undergoing epilepsy surgery under local anesthesia.[2] This procedure was used to explore the functional anatomy of the brain, mapping speech areas and identifying the somatosensory and somatomotor cortex areas to be excluded from surgical removal. A doctor named Robert Galbraith Heath was also an early researcher of the brain at the Tulane University School of Medicine.[3][4]

Electrophysiological basis[edit]

ECoG signals are composed of synchronized postsynaptic potentials (local field potentials), recorded directly from the exposed surface of the cortex. The potentials occur primarily in cortical pyramidal cells, and thus must be conducted through several layers of the cerebral cortex, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), pia mater, and arachnoid mater before reaching subdural recording electrodes placed just below the dura mater (outer cranial membrane). However, to reach the scalp electrodes of a conventional electroencephalogram (EEG), electrical signals must also be conducted through the skull, where potentials rapidly attenuate due to the low conductivity of bone. For this reason, the spatial resolution of ECoG is much higher than EEG, a critical imaging advantage for presurgical planning.[5] ECoG offers a temporal resolution of approximately 5 ms and spatial resolution as low as 1-100 µm.[6]

Using depth electrodes, the local field potential gives a measure of a neural population in a sphere with a radius of 0.5–3 mm around the tip of the electrode.[7] With a sufficiently high sampling rate (more than about 10 kHz), depth electrodes can also measure action potentials.[8] In which case the spatial resolution is down to individual neurons, and the field of view of an individual electrode is approximately 0.05–0.35 mm.[7]

Procedure[edit]

The ECoG recording is performed from electrodes placed on the exposed cortex. In order to access the cortex, a surgeon must first perform a craniotomy, removing a part of the skull to expose the brain surface. This procedure may be performed either under general anesthesia or under local anesthesia if patient interaction is required for functional cortical mapping. Electrodes are then surgically implanted on the surface of the cortex, with placement guided by the results of preoperative EEG and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Electrodes may either be placed outside the dura mater (epidural) or under the dura mater (subdural). ECoG electrode arrays typically consist of sixteen sterile, disposable stainless steel, carbon tip, platinum, Platinum-iridium alloy or gold ball electrodes, each mounted on a ball and socket joint for ease in positioning. These electrodes are attached to an overlying frame in a "crown" or "halo" configuration.[9] Subdural strip and grid electrodes are also widely used in various dimensions, having anywhere from 4 to 256[10] electrode contacts. The grids are transparent, flexible, and numbered at each electrode contact. Standard spacing between grid electrodes is 1 cm; individual electrodes are typically 5 mm in diameter. The electrodes sit lightly on the cortical surface, and are designed with enough flexibility to ensure that normal movements of the brain do not cause injury. A key advantage of strip and grid electrode arrays is that they may be slid underneath the dura mater into cortical regions not exposed by the craniotomy. Strip electrodes and crown arrays may be used in any combination desired. Depth electrodes may also be used to record activity from deeper structures such as the hippocampus.

DCES[edit]

Direct cortical electrical stimulation (DCES), also known as cortical stimulation mapping, is frequently performed in concurrence with ECoG recording for functional mapping of the cortex and identification of critical cortical structures.[9] When using a crown configuration, a handheld wand bipolar stimulator may be used at any location along the electrode array. However, when using a subdural strip, stimulation must be applied between pairs of adjacent electrodes due to the nonconductive material connecting the electrodes on the grid. Electrical stimulating currents applied to the cortex are relatively low, between 2 and 4 mA for somatosensory stimulation, and near 15 mA for cognitive stimulation.[9] The stimulation frequency is usually 60 Hz in North America and 50 Hz in Europe, and any charge density more than 150 μC/cm2 causes tissue damage.[11][12]

The functions most commonly mapped through DCES are primary motor, primary sensory, and language. The patient must be alert and interactive for mapping procedures, though patient involvement varies with each mapping procedure. Language mapping may involve naming, reading aloud, repetition, and oral comprehension; somatosensory mapping requires that the patient describe sensations experienced across the face and extremities as the surgeon stimulates different cortical regions.[9]

Clinical applications[edit]

Since its development in the 1950s, ECoG has been used to localize epileptogenic zones during presurgical planning, map out cortical functions, and to predict the success of epileptic surgical resectioning. ECoG offers several advantages over alternative diagnostic modalities:

- Flexible placement of recording and stimulating electrodes[2]

- Can be performed at any stage before, during, and after a surgery

- Allows for direct electrical stimulation of the brain, identifying critical regions of the cortex to be avoided during surgery

- Greater precision and sensitivity than an EEG scalp recording – spatial resolution is higher and signal-to-noise ratio is superior due to closer proximity to neural activity

Limitations of ECoG include:

- Limited sampling time – seizures (ictal events) may not be recorded during the ECoG recording period

- Limited field of view – electrode placement is limited by the area of exposed cortex and surgery time, sampling errors may occur

- Recording is subject to the influence of anesthetics, narcotic analgesics, and the surgery itself[2]

Intractable epilepsy[edit]

Epilepsy is currently ranked as the third most commonly diagnosed neurological disorder, afflicting approximately 2.5 million people in the United States alone.[13] Epileptic seizures are chronic and unrelated to any immediately treatable causes, such as toxins or infectious diseases, and may vary widely based on etiology, clinical symptoms, and site of origin within the brain. For patients with intractable epilepsy – epilepsy that is unresponsive to anticonvulsants – surgical treatment may be a viable treatment option. Partial epilepsy[14] is the common intractable epilepsy and the partial seizure is difficult to locate.Treatment for such epilepsy is limited to attachment of vagus nerve stimulator. Epilepsy surgery is the cure for partial epilepsy provided that the brain region generating seizure is carefully and accurately removed.

- Extraoperative ECoG

Before a patient can be identified as a candidate for resectioning surgery, MRI must be performed to demonstrate the presence of a structural lesion within the cortex, supported by EEG evidence of epileptogenic tissue.[2] Once a lesion has been identified, ECoG may be performed to determine the location and extent of the lesion and surrounding irritative region. The scalp EEG, while a valuable diagnostic tool, lacks the precision necessary to localize the epileptogenic region. ECoG is considered to be the gold standard for assessing neuronal activity in patients with epilepsy, and is widely used for presurgical planning to guide surgical resection of the lesion and epileptogenic zone.[15][16] The success of the surgery depends on accurate localization and removal of the epileptogenic zone. ECoG data is assessed with regard to ictal spike activity – "diffuse fast wave activity" recorded during a seizure – and interictal epileptiform activity (IEA), brief bursts of neuronal activity recorded between epileptic events. ECoG is also performed following the resectioning surgery to detect any remaining epileptiform activity, and to determine the success of the surgery. Residual spikes on the ECoG, unaltered by the resection, indicate poor seizure control, and incomplete neutralization of the epileptogenic cortical zone. Additional surgery may be necessary to completely eradicate seizure activity. Extraoperative ECoG is also used to localize functionally-important areas (also known as eloquent cortex) to be preserved during epilepsy surgery. [17] Motor, sensory, cognitive tasks during extraoperative ECoG are reported to increase the amplitude of high-frequency activity at 70–110 Hz in areas involved in execution of given tasks.[17][18][19] Task-related high-frequency activity can animate 'when' and 'where' cerebral cortex is activated and inhibited in a 4D manner with a temporal resolution of 10 milliseconds or below and a spatial resolution of 10 mm or below.[18][19]

- Intraoperative ECoG

The objective of the resectioning surgery is to remove the epileptogenic tissue without causing unacceptable neurological consequences. In addition to identifying and localizing the extent of epileptogenic zones, ECoG used in conjunction with DCES is also a valuable tool for functional cortical mapping. It is vital to precisely localize critical brain structures, identifying which regions the surgeon must spare during resectioning (the "eloquent cortex") in order to preserve sensory processing, motor coordination, and speech. Functional mapping requires that the patient be able to interact with the surgeon, and thus is performed under local rather than general anesthesia. Electrical stimulation using cortical and acute depth electrodes is used to probe distinct regions of the cortex in order to identify centers of speech, somatosensory integration, and somatomotor processing. During the resectioning surgery, intraoperative ECoG may also be performed to monitor the epileptic activity of the tissue and ensure that the entire epileptogenic zone is resectioned.

Although the use of extraoperative and intraoperative ECoG in resectioning surgery has been an accepted clinical practice for several decades, recent studies have shown that the usefulness of this technique may vary based on the type of epilepsy a patient exhibits. Kuruvilla and Flink reported that while intraoperative ECoG plays a critical role in tailored temporal lobectomies, in multiple subpial transections (MST), and in the removal of malformations of cortical development (MCDs), it has been found impractical in standard resection of medial temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) with MRI evidence of mesial temporal sclerosis (MTS).[2] A study performed by Wennberg, Quesney, and Rasmussen demonstrated the presurgical significance of ECoG in frontal lobe epilepsy (FLE) cases.[20]

Research applications[edit]

ECoG has recently emerged as a promising recording technique for use in brain-computer interfaces (BCI).[21] BCIs are direct neural interfaces that provide control of prosthetic, electronic, or communication devices via direct use of the individual's brain signals. Brain signals may be recorded either invasively, with recording devices implanted directly into the cortex, or noninvasively, using EEG scalp electrodes. ECoG serves to provide a partially invasive compromise between the two modalities – while ECoG does not penetrate the blood–brain barrier like invasive recording devices, it features a higher spatial resolution and higher signal-to-noise ratio than EEG.[21] ECoG has gained attention recently for decoding imagined speech or music, which could lead to "literal" BCIs[22] in which users simply imagine words, sentences, or music that the BCI can directly interpret.[23][24]

In addition to clinical applications to localize functional regions to support neurosurgery, real-time functional brain mapping with ECoG has gained attention to support research into fundamental questions in neuroscience. For example, a 2017 study explored regions within face and color processing areas and found that these subregions made highly specific contributions to different aspects of vision.[25] Another study found that high-frequency activity from 70 to 200 Hz reflected processes associated with both transient and sustained decision-making.[26] Other work based on ECoG presented a new approach to interpreting brain activity, suggesting that both power and phase jointly influence instantaneous voltage potential, which directly regulates cortical excitability.[27] Like the work toward decoding imagined speech and music, these research directions involving real-time functional brain mapping also have implications for clinical practice, including both neurosurgery and BCI systems. The system that was used in most of these real-time functional mapping publications, "CortiQ". has been used for both research and clinical applications.

Recent advances[edit]

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2022) |

The electrocorticogram is still considered to be the "gold standard" for defining epileptogenic zones; however, this procedure is risky and highly invasive. Recent studies have explored the development of a noninvasive cortical imaging technique for presurgical planning that may provide similar information and resolution of the invasive ECoG.

In one novel approach, Lei Ding et al.[28] seek to integrate the information provided by a structural MRI and scalp EEG to provide a noninvasive alternative to ECoG. This study investigated a high-resolution subspace source localization approach, FINE (first principle vectors) to image the locations and estimate the extents of current sources from the scalp EEG. A thresholding technique was applied to the resulting tomography of subspace correlation values in order to identify epileptogenic sources. This method was tested in three pediatric patients with intractable epilepsy, with encouraging clinical results. Each patient was evaluated using structural MRI, long-term video EEG monitoring with scalp electrodes, and subsequently with subdural electrodes. The ECoG data were then recorded from implanted subdural electrode grids placed directly on the surface of the cortex. MRI and computed tomography images were also obtained for each subject.

The epileptogenic zones identified from preoperative EEG data were validated by observations from postoperative ECoG data in all three patients. These preliminary results suggest that it is possible to direct surgical planning and locate epileptogenic zones noninvasively using the described imaging and integrating methods. EEG findings were further validated by the surgical outcomes of all three patients. After surgical resectioning, two patients are seizure-free and the third has experienced a significant reduction in seizures. Due to its clinical success, FINE offers a promising alternative to preoperative ECoG, providing information about both the location and extent of epileptogenic sources through a noninvasive imaging procedure.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Palmini, A (2006). "The concept of the epileptogenic zone: A modern look at Penfield and Jasper's views on the role of interictal spikes". Epileptic Disorders. 8 (Suppl 2): S10–5. doi:10.1684/j.1950-6945.2006.tb00205.x. hdl:10923/21709. PMID 17012068.

- ^ a b c d e Kuruvilla, A; Flink, R (2003). "Intraoperative electrocorticography in epilepsy surgery: Useful or not?". Seizure. 12 (8): 577–84. doi:10.1016/S1059-1311(03)00095-5. PMID 14630497. S2CID 15643130.

- ^ Baumeister AA (2000). "The Tulane Electrical Brain Stimulation Program a historical case study in medical ethics". J Hist Neurosci. 9 (3): 262–78. doi:10.1076/jhin.9.3.262.1787. PMID 11232368. S2CID 38336466.

- ^ Marwan Hariz; Patric Blomstedt; Ludvic Zrinzo (2016). "Deep Brain Stimulation between 1947 and 1987: The Untold Story". Neurosurg Focus. 29 (2). e1 – via Medscape.

- ^ Hashiguchi, K; Morioka, T; Yoshida, F; Miyagi, Y; et al. (2007). "Correlation between scalp-recorded electroencephalographic and electrocorticographic activities during ictal period". Seizure. 16 (3): 238–247. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2006.12.010. PMID 17236792. S2CID 1728557.

- ^ Fallegger, Florian; Schiavone, Giuseppe; Pirondini, Elvira; Wagner, Fabien B.; Vachicouras, Nicolas; Serex, Ludovic; Zegarek, Gregory; May, Adrien; Constanthin, Paul; Palma, Marie; Khoshnevis, Mehrdad; Van Roost, Dirk; Yvert, Blaise; Courtine, Grégoire; Schaller, Karl (March 2021). "MRI-Compatible and Conformal Electrocorticography Grids for Translational Research". Advanced Science. 8 (9). doi:10.1002/advs.202003761. ISSN 2198-3844. PMC 8097365. PMID 33977054.

- ^ a b Logothetis, NK (2003). "The underpinning of the BOLD functional magnetic resonance imaging signal". The Journal of Neuroscience. 23 (10): 3963–71. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-03963.2003. PMC 6741096. PMID 12764080.

- ^ Ulbert, I; Halgren, E; Heit, G; Karmos, G (2001). "Multiple microelectrode-recording system for human intracortical applications". Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 106 (1): 69–79. doi:10.1016/S0165-0270(01)00330-2. PMID 11248342. S2CID 12203755.

- ^ a b c d Schuh, L; Drury, I (1996). "Intraoperative electrocorticography and direct cortical electrical stimulation". Seminars in Anesthesia. 16: 46–55. doi:10.1016/s0277-0326(97)80007-4.

- ^ Mesgarani, N; Chang, EF (2012). "Selective cortical representation of attended speaker in multi-talker speech perception". Nature. 485 (7397): 233–6. Bibcode:2012Natur.485..233M. doi:10.1038/nature11020. PMC 3870007. PMID 22522927.

- ^ Boyer A, Duffau H, Vincent M, Ramdani S, Mandonnet E, Guiraud D, Bonnetblanc F (2018). "Electrophysiological Activity Evoked by Direct Electrical Stimulation of the Human Brain: Interest of the P0 Component" (PDF). 2018 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC). Vol. 2018. pp. 2210–2213. doi:10.1109/EMBC.2018.8512733. ISBN 978-1-5386-3646-6. PMID 30440844. S2CID 53097668.

- ^ Ritaccio, Anthony L.; Brunner, Peter; Schalk, Gerwin (March 2018). "Electrical Stimulation Mapping of the Brain: Basic Principles and Emerging Alternatives". Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology. 35 (2): 86–97. doi:10.1097/WNP.0000000000000440. ISSN 0736-0258. PMC 5836484. PMID 29499015."frequency" on page 6, "damage" on page 3 of pdf

- ^ Kohrman, M (2007). "What is epilepsy? Clinical perspectives in the diagnosis and treatment". Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology. 24 (2): 87–95. doi:10.1097/WNP.0b013e3180415b51. PMID 17414964. S2CID 35146214.

- ^ Wetjen, Nicholas M.; Marsh, W. Richard; Meyer, Fredric B.; Cascino, Gregory D.; So, Elson; Britton, Jeffrey W.; Stead, S. Matthew; Worrell, Gregory A. (June 2009). "Intracranial electroencephalography seizure onset patterns and surgical outcomes in nonlesional extratemporal epilepsy: Clinical article". Journal of Neurosurgery. 110 (6): 1147–1152. doi:10.3171/2008.8.JNS17643. ISSN 0022-3085. PMC 2841508. PMID 19072306.

- ^ Sugano, H; Shimizu, H; Sunaga, S (2007). "Efficacy of intraoperative electrocorticography for assessing seizure outcomes in intractable epilepsy patients with temporal-lobe-mass lesions". Seizure. 16 (2): 120–127. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2006.10.010. PMID 17158074.

- ^ Miller, KJ; denNijs, M; Shenoy, P; Miller, JW; et al. (2007). "Real-time functional brain mapping using electrocorticography". NeuroImage. 37 (2): 504–507. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.05.029. PMID 17604183. S2CID 3362496.

- ^ a b Crone, NE; Miglioretti, DL; Gordon, B; Lesser, RP (1998). "Functional mapping of human sensorimotor cortex with electrocorticographic spectral analysis. II. Event-related synchronization in the gamma band". Brain. 121 (12): 2301–15. doi:10.1093/brain/121.12.2301. PMID 9874481.

- ^ a b Nakai, Y; Jeong, JW; Brown, EC; Rothermel, R; Kojima, K; Kambara, T; Shah, A; Mittal, S; Sood, S; Asano, E (2017). "Three- and four-dimensional mapping of speech and language in patients with epilepsy". Brain. 140 (5): 1351–1370. doi:10.1093/brain/awx051. PMC 5405238. PMID 28334963.

- ^ a b Nakai, Ya; Nagashima, A; Hayakawa, A; Osuki, T; Jeong, JW; Sugiura, A; Brown, EC; Asano, E (2018). "Four-dimensional map of the human early visual system". Clin Neurophysiol. 129 (1): 188–197. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2017.10.019. PMC 5743586. PMID 29190524.

- ^ Wennberg, R; Quesney, F; Olivier, A; Rasmussen, T (1998). "Electrocorticography and outcome in frontal lobe epilepsy". Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 106 (4): 357–68. doi:10.1016/S0013-4694(97)00148-X. PMID 9741764.

- ^ a b Shenoy, P; Miller, KJ; Ojemann, JG; Rao, RPN (2007). "Generalized features for electrocorticographic BCIs" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 55 (1): 273–80. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.208.7298. doi:10.1109/TBME.2007.903528. PMID 18232371. S2CID 3034381. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-12-14.

- ^ Allison, Brendan Z. (2009). "Chapter 2: Toward Ubiquitous BCIs.". Brain-Computer Interfaces. Springer. pp. 357–387. ISBN 978-3-642-02091-9.

- ^ Swift, James; Coon, William; Guger, Christoph; Brunner, Peter; Bunch, M; Lynch, T; Frawley, T; Ritaccio, Anthony; Schalk, Gerwin (2018). "Passive functional mapping of receptive language areas using electrocorticographic signals". Clinical Neurophysiology. 6 (12): 2517–2524. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2018.09.007. PMC 6414063. PMID 30342252.

- ^ Martin, Stephanie; Iturrate, Iñaki; Millán, José del R.; Knight, Robert; Pasley, Brian N. (2018). "Decoding Inner Speech Using Electrocorticography: Progress and Challenges Toward a Speech Prosthesis". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 12: 422. doi:10.3389/fnins.2018.00422. PMC 6021529. PMID 29977189.

- ^ Schalk, Gerwin; Kapeller, Christoph; Guger, Christoph; Ogawa, H; Hiroshima, S; Lafer-Sousa, R; Saygin, Zenyip M.; Kamada, Kyousuke; Kanwisher, Nancy (2017). "Facephenes and rainbows: Causal evidence for functional and anatomical specificity of face and color processing in the human brain". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 114 (46): 12285–12290. Bibcode:2017PNAS..11412285S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1713447114. PMC 5699078. PMID 29087337.

- ^ Saez, I; Lin, J; Stolk, A; Chang, E; Parvizi, J; Schalk, Gerwin; Knight, Robert T.; Hsu, M. (2018). "Encoding of Multiple Reward-Related Computations in Transient and Sustained High-Frequency Activity in Human OFC". Current Biology. 28 (18): 2889–2899.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.07.045. PMC 6590063. PMID 30220499.

- ^ Schalk, Gerwin; Marple, J.; Knight, Robert T.; Coon, William G. (2017). "Instantaneous voltage as an alternative to power- and phase-based interpretation of oscillatory brain activity". NeuroImage. 157: 545–554. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.06.014. PMC 5600843. PMID 28624646.

- ^ Ding, L; Wilke, C; Xu, B; Xu, X; et al. (2007). "EEG source imaging: Correlating source locations and extents with electrocorticography and surgical resections in epilepsy patients". Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology. 24 (2): 130–136. doi:10.1097/WNP.0b013e318038fd52. PMC 2758789. PMID 17414968.

Brain–computer interface[edit]

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (April 2024) |

| Neuropsychology |

|---|

|

A brain–computer interface (BCI), sometimes called a brain–machine interface (BMI), is a direct communication pathway between the brain's electrical activity and an external device, most commonly a computer or robotic limb. BCIs are often directed at researching, mapping, assisting, augmenting, or repairing human cognitive or sensory-motor functions.[1] They are often conceptualized as a human–machine interface that skips the intermediary component of the physical movement of body parts, although they also raise the possibility of the erasure of the discreteness of brain and machine. Implementations of BCIs range from non-invasive (EEG, MEG, MRI) and partially invasive (ECoG and endovascular) to invasive (microelectrode array), based on how close electrodes get to brain tissue.[2]

Research on BCIs began in the 1970s by Jacques Vidal at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) under a grant from the National Science Foundation, followed by a contract from DARPA.[3][4] Vidal's 1973 paper marks the first appearance of the expression brain–computer interface in scientific literature.

Due to the cortical plasticity of the brain, signals from implanted prostheses can, after adaptation, be handled by the brain like natural sensor or effector channels.[5] Following years of animal experimentation, the first neuroprosthetic devices implanted in humans appeared in the mid-1990s.

Recently, studies in human-computer interaction via the application of machine learning to statistical temporal features extracted from the frontal lobe (EEG brainwave) data has had high levels of success in classifying mental states (relaxed, neutral, concentrating),[6] mental emotional states (negative, neutral, positive),[7] and thalamocortical dysrhythmia.[8]

History[edit]

The history of brain–computer interfaces (BCIs) starts with Hans Berger's discovery of the electrical activity of the human brain and the development of electroencephalography (EEG). In 1924 Berger was the first to record human brain activity by means of EEG. Berger was able to identify oscillatory activity, such as Berger's wave or the alpha wave (8–13 Hz), by analyzing EEG traces.

Berger's first recording device was very rudimentary. He inserted silver wires under the scalps of his patients. These were later replaced by silver foils attached to the patient's head by rubber bandages. Berger connected these sensors to a Lippmann capillary electrometer, with disappointing results. However, more sophisticated measuring devices, such as the Siemens double-coil recording galvanometer, which displayed electric voltages as small as one ten thousandth of a volt, led to success.

Berger analyzed the interrelation of alternations in his EEG wave diagrams with brain diseases. EEGs permitted completely new possibilities for the research of human brain activities.

Although the term had not yet been coined, one of the earliest examples of a working brain-machine interface was the piece Music for Solo Performer (1965) by the American composer Alvin Lucier. The piece makes use of EEG and analog signal processing hardware (filters, amplifiers, and a mixing board) to stimulate acoustic percussion instruments. To perform the piece one must produce alpha waves and thereby "play" the various percussion instruments via loudspeakers which are placed near or directly on the instruments themselves.[9]

UCLA Professor Jacques Vidal coined the term "BCI" and produced the first peer-reviewed publications on this topic.[3][4] Vidal is widely recognized as the inventor of BCIs in the BCI community, as reflected in numerous peer-reviewed articles reviewing and discussing the field (e.g.,[10][11][12]). A review pointed out that Vidal's 1973 paper stated the "BCI challenge"[13] of controlling external objects using EEG signals, and especially use of Contingent Negative Variation (CNV) potential as a challenge for BCI control. The 1977 experiment Vidal described was the first application of BCI after his 1973 BCI challenge. It was a noninvasive EEG (actually Visual Evoked Potentials (VEP)) control of a cursor-like graphical object on a computer screen. The demonstration was movement in a maze.[14]

After his early contributions, Vidal was not active in BCI research, nor BCI events such as conferences, for many years. In 2011, however, he gave a lecture in Graz, Austria, supported by the Future BNCI project, presenting the first BCI, which earned a standing ovation. Vidal was joined by his wife, Laryce Vidal, who previously worked with him at UCLA on his first BCI project.

In 1988, a report was given on noninvasive EEG control of a physical object, a robot. The experiment described was EEG control of multiple start-stop-restart of the robot movement, along an arbitrary trajectory defined by a line drawn on a floor. The line-following behavior was the default robot behavior, utilizing autonomous intelligence and autonomous source of energy.[15][16] This 1988 report written by Stevo Bozinovski, Mihail Sestakov, and Liljana Bozinovska was the first one about a robot control using EEG.[17][18]

In 1990, a report was given on a closed loop, bidirectional adaptive BCI controlling computer buzzer by an anticipatory brain potential, the Contingent Negative Variation (CNV) potential.[19][20] The experiment described how an expectation state of the brain, manifested by CNV, controls in a feedback loop the S2 buzzer in the S1-S2-CNV paradigm. The obtained cognitive wave representing the expectation learning in the brain is named Electroexpectogram (EXG). The CNV brain potential was part of the BCI challenge presented by Vidal in his 1973 paper.