User:Vktranslate

University of Freiburg

Wintersemester 15/16

Link to: User:AnTransit

Translation 1 / Ahoy[edit]

German, distribution

Research

To German readers the term remained widely unknown until the 1840’s, because translators of popular maritime literature of that time often avoided it. In 1843, the German translation of the word "å-hoj" was still "hiaho" in a swedish novel. In 1847, the English ahoy was translated into the German "holla!", and the expressions all hands ahoy!, all hands (a-)hoay! , were translated into "Alles auf’s Verdeck! Überall! Überall!" [1]

The earliest evidence in the German does not derive from factual nautical texts, but is taken from maritime prose. In the beginning, the circumstances point to uncertainties regarding the usage of the word. Since the late 1820’s ahoy and ahoi marked with the final sound –i, a feature demonstrating the Germanisation of ahoy, can be found in translations of English novels and narratives. Almost simultaneously authors start to use it in German original texts, even though rarely at first. From the mid-1840’s onward, the term was used by many widely-read authors, so that ahoi was can be regarded as established around 1850. [2]

Entries in dictionaries remained rare in the 19th century. It is not included in the "Urduden" of 1880. The Grimm brothers’ Dictonary of German (Deutsches Wörterbuch) did not yet know the word; the first sheet with entries up to the keyword "allverein" was published in 1852. The DWB’s second edition of 1998, names 1846 and 1848 as the earliest years of documentation. [3] In additon, the original index cards for the dictionary, which are kept in the Berlin-Brandenburg Acadamy of Sciences, do not contain any earlier entries. The standard work "Etymological Dictionary of German" (Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache) by Friedrich Kluge lists ahoi as an isolated keyword only since the issue of 1999.[4]

The automatic search for appropriate keywords in digitalized books on the internet and in offline-databanks does only yields a few useful results. German light fiction was printed so badly in the first half of the 19th century that even today good recognition software still produces a great number of errors, so that records are not found. Research in original catalogs is still necessary for a systematic search.[5]

-

ahoi first appeared in 1828, in German translations of James Fenimore Cooper novels

Early evidence in German original texts - second half

[...]

In one of Ernst Willkomm's stories from 1838, Jans, one of the characters in the story shouts “ship ahoy” as loud a thunder from the cliffs of Heligoland. The German newspaper Zeitung für die elegante Welt (English: "Newspaper for the Elegant World"), in which Wilkomm’s Lootsenerzählungen (English: "Pilot Stories") appeared first, misprinted this call to “ship ahni!”. However, the misspelling was corrected when the story was published in a book in 1842. In the same year the newspaper released the narrative, an anonymous author, apparently not knowing the meaning of the word, quotes several sailors loading a ship in the narrative Johann Pol. Ein Lebensbild auf den Antillen (English:Johann Pol. An image of life in the west indies), “who sung their monotonous Ahoi, ohe!” that is sung by sailors of all nations around the world during work.”

Politik an einer Wirthstafel a by Friedrich Giehne, which mentions that the waitress of a pub was called over by “Waitress! Ahoi!”, dates back to 1844. The book in which also Giehne’s text was published, mostly holds reprints of texts from 1836 to 1843. However, the preface does neither tell anything about the time frame in which Politik an einer Wirthstafel was first published, nor does it say whether the text even is a reprint. It is astonishing that the exclamation was not only used at sea but also ashore. One such example of the usage ashore is found in Smollett’s novel The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle of 1751 where the commodore Trunnion shouts “Ho! the house a hoy!”. A connection between Smollet and Giehne is easy to imagine. It is likely that Giehne has read a tranlation of Smollet's work by Georg Nikolaus Bärmann from English to German in 1840, in which Trunnion calls: „Halloh, Wirtshaus, ahoi!“.[6]

Heinrich Smidt, a german author, used the term ahoi in 1844 in parts of the pre-print of his novel Michael de Ruiter. Bilder aus Holland’s Marine (English: "Michael de Ruiter. Pictures of Holland's Marine") which was published in 1846 in the German magazine Magazin für die Literatur des Auslandes (English: "Magazine for the literature from abroad") [7], of which he was the editor. In 1844, ahoi also appeared in his story Hexen-Bootsmann. In recently digitized versions of Smidt's books originally published between 1837 and 1842 he did not use ahoi. From then on, however, he used the term steadily all throughout his last novel, which was published in 1866. According to that, the word must have become part of Smidt’s vocabulary around 1843.[8]

-

Since 1844, Ahoi often appears in writings by the German sailor and author Heinrich Smidt

Friedrich Gerstäcker was one of the most successful and popular German authors of adventure novels in the 19th century. As was the case with Smidt who started using Ahoy in 1844, Gerstäcker, who translated a lot from the English, also suddenly used the term in 1847. "Ahoi – ho – ahoi! meine braven Burschen" (English: “Ahoi – ho – ahoi! My well behaved fellows”) , is what he writes in the Mississippi pictures. In 1848 the sentence: “Boot ahoi! schrie da plötzlich der gebundene Steuermann“ (English: Ship ahoi! shouted the (?) helmsman

suddenly”), appeared in Gerstäcker’s novel Flusspiraten des Mississippi (English: The Mississippi River Pirates).

-

In 1848, Friedrich Gerstäcker popularized ahoi in his bestseller Die Flusspiraten des Mississippi (English:The Mississippi River Pirates)

Germany, usage

The Maritime

To the globetrotter Wilhelm Heine the term ahoi was "common" in 1859. [9] Heine however, was travelling with American seaman, who already used the common English variant of the term. In 1864, a dictionary for German people in Livland, a historic region along the Baltic sea, describes the usage of ahoi like this: “ahoi […], disyllabic, with stress on second syllable”. [10] In the 19th century in Germany, since ahoi was “generally rather rarely” [11], and around 1910 a “modern imitation” [12] of the English ahoy, the term dropped out of use. [13] In the non-nautical domain, ahoi is also used when saying goodbye. [14] In German literature, most of them dealing with maritime topics, ahoi appears for example in:

- Paul Heyse (1900): “He looked up to the threatening clouds jauntily and challenging, and shouted out a bright Ahoi!”[15]

- Carl Sternheim (1909) as a message to the crew: “A voice from the mast: Land ahoi!” [16]

- Anna Seghers (1928): “Some fellows from the front ran up a hill, shouted Ahoi, waving their arms.” [17]

- Hans Fallada (1934) as shout of warning: “Ahoi! Ahoi! Man overboard!” [18]

- Friedrich Dürrenmatt (1951): “Ahoi! Loosened the sails, away to other coasts, to other brides!” [19]

- Günter Grass (1959): “But why Matzerath was waving and shouting such the nonsense ‘ship ahoi’, remained obscure to me. Since he, as a native Rhinelander, did not know anything about the navy.” [20]

- Hermann Kant (1972): “There the person walked out of the house, said ahoi, Franziska, left a kiss on the nose, just as usual…”[21]

- Ulrich Plenzdorf (1973): “Ahoi! You were coughing a lot better once, weren’t you?” [22]

USA, telephone communication

In the USA, the inventors Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas Alva Edison, were not only in competition for the invention of the telephone, but were also competing about what one shoulkd say when they pick up the phone. Bell favored the term ahoyand he used it until his death [23]and he claimed never to have said “hello”. [24] Edison's choice "hello" settled the dispute in his favor within a few years. It is unlikely that a dichotomy of the terms existed in the beginning phases of the history of the telephone.

-

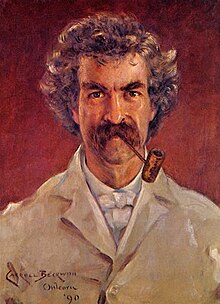

Actor portraying Alexander Graham Bell in an AT&T promotional film (1926)

Bell's ahoy

The wide spread belief following Bell's death that Ahoy! Ahoy! supposedly were the first words ever spoken on a telephone , turned out to be false. Former inventors of telephones already made a transmission of speech possible. Besides, Bell’s first words addressed to his mechanic Thomas A. Watson, who was in the room next to Bell, on March 10th, 1876, were: “Mr. Watson – come here – I want to see you”. [25] Bell’s choice of words was proven since the early telephone was able to transmit a dialogue, not only one-way messages. On October 9th, 1876, Bell used the maritime term during the first two way public phone call between Boston and East Cambridge, which were two miles apart. Watson, who was held up by a technical problem, recalled: “More loudly and more distinctly as I had ever heard it between the two rooms, Bell’s voice was vibrating [from the relay] and shouting: ‘Ahoy! Ahoy! Are you there? What is going on?’ I could even hear that he was becoming hoarse, because he had been shouting all the time whilst I was walking through the factory. I ‘ahoyed’ back at him and could hear him sigh as he asked me: ‘Where have you been all the time?’”[26]

Since the end of October 1876, Bell regularly opened his phone calls within Watson in Cambridge with the question: “Ahoy, Watson are you there?“ [27]On December the 3rd, 1876, Bell used the familiar[28] term again, when he started a long-distance call with Watson in front of an audience to North Conway in New Hampshire, over (?) a 143 mile telegraph wire by the Eastern Railroad, with the words: „Ahoy! Ahoy! Watson, are you there?“[29] On February 12th 1877, when Watson was in Salem and Bell in Boston, Watson started the public conversation with “Ahoy! Ahoy!”. That Bell used the variation ahoy-hoy [30], serving as an alteration to his common double ahoy ahoy[31], cannot be proven.

Supposedly, ahoy-ahoy has also been the first call by a telephonist and probably dates back to the year 1878. These possible speakers could be Louis Herrick Frost, the first regularly employed boy operator, or George Willard Coy, who opened up a commercial telephone agency on January 28th 1878 in New Haven, Connecticut. He became the first full-time operator. [32]

Reception

Alluding to the segmentation of the US telephone monopoly AT&T in 1984, William Safire said: “… thus, Ahoy! became A.T.&T.’s first divestiture“.[33] AT&T developed from Bell’s telephone company, which was established in 1877.

The tension regarding the usage of ahoy and hello was used in various media contexts and was observed in literary theory:

- The English speaking writer Oswald Kendall used it in a novel in 1916: “ American ship ahoy!’ , the voice was calling. […] ‘Hello!’ responded Captain Hawks and I could hear laughter in his tone, the laughter of pleasure. ”[34]

- Montgomery Burns, owner of a nuclear power plant in the comic TV-series The Simpsons, used ahoy!hoy![35] on the phone, which in one episode, is answered by his incompetent employee Homer Simpson with hello.[36]

- A literary scholar recognized a semantic conformity of the water-like electricity terminology (wave, river, stream) in the telephone service, with the nautical ahoy being used to start a telephone conversation. As well as the hallo being in unison with the French à l‘eau, which also is “zum Wasser” in German. [37]

The inferior ahoy

As yet, it has not been investigated how Edison's term managed to win over Bell's. Related literature names social and technical reasons for that.

There was a huge public demand for a short word, since at the beginning longer expressions of opening a conversation on the phone like “What is wanted?” [38] or “Are you ready to talk?” were used. Supposedly, one day Edison simply said “hello” to open a call, instead of using the rather “un-American” inconvenient expressions [39]. Hello, though not yet being the conventional form to greet someone on the phone at that time, allowed to get to the point more quickly [40]. Furthermore, ahoy was tradiotionally followed by the name of an addresee, but this addition was not possible at the beginning of an incoming anonymous phone call. Besides, since ahoy was a maritime term, it was considered to be too manly, once women were hired as telephone operators. As the US-columnist William Safire summarized: Ahoy was too maritime for land-and telephone man and the formula was unsuitable for a conversation.[41]

Bell and Edison followed different technical concepts in their inventions. While Bell was planning to offer new connections to the customers each time they were in need of a conversation, Edison in turn favored stable lines that stay open all the time between the participants of the phone call.

To get a hold of someone you call, Edison thought in 1877 that it was necessary to have a loud word, which can be heard over along distance.

To use a bell that can be heard through the telephone line, was an idea taken into consideration; however, the word bell reminded Edison of his competitor. When Bell’s single-line concept won over Edison’s idea, Edison began to build the switchboards that were needed, but supposedly used his term hello, in the user manuals for the telephone operators. [42] In 1880, Hello became the established way of greeting someone on the phone in New York.[43] The participants of the first telephone conference of telephone companies in November 1880 in Niagara Falls wore a Hello badge. [44] In 1883 it was proven, that Hello girl was an expression referring to young women working as telephone operators, and it was popularized by the American author Mark Twain in 1889.[45]

Translation 2 / Lorettoberg[edit]

The Lorettoberg, also known as Josephsbergle in Freiburg, is a mountain ridge in the South-West of the Wiehre district in the city of Freiburg im Breisgau in Germany. The mountain, with its elevation of 384,5 meters above sea level[46], is wooded at its peak. It divides the district Unterwiehre-Süd and borders the Vauban district in the West. 500 meters north of the “peak” there is a high spur 348m above sea level [47], next to which the eponymous Lorettokapelle is located. The name derives from Loreto, the second biggest Italian (Mary-) pilgrimage destination, after the St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. The Schloss-Café is located at the top of the mountain making the Lorettoberg a popular destination for a getaway, strolling and a local recreation area.

The eastern main edge fault of the Upper Rhine Rift drags through Lorettoberg and the Höllentalbahn runs through the mountain via the Lorettotunnel. When the tunnel was built, a “geological window” was left open, through which the fault can be seen and where further decline of the Upper Rhine Rift can be measured.[48]

Buildings[edit]

The 22,6 meter high Hildaturm has been standing on the spur at the north side of the summit since 1886. [49]. It is built in the style of a medieval Bergfried and is a memorial of the day when Princess Hilda of Nassau, the last Grand Duchess of Baden, moved to Freiburg following her marriage to the Grand Duke of Baden, Friedrich II.[50] [51]During World War II, the Hildaturm was used for aerial servaillance and obeservation. [52] During summer, the 19,86 meter high observation deck is open to public on selected days of the week.

A little north of the Hildaturm, the Lorettokapelle, which consists of three single chapels and was founded by citizens of Freiburg in 1657, can be found. It is reminiscent of the bloody fights for the Lorettoberg in 1644 (Battle of Freiburg), which was, among others, described by the poet Reinhold Schneider, who lived at the Loretto Mountain. Next to the Lorettokapelle, there is the “Schloss-Café” in the Guesthouse of the Lorettoberg, which was built in 1902 in the Art Nouveau style. Before that, at the same place, there was the so called “Bruderhaus” (Brother house) that was build in the 19th century. This house however, was too small to host all the visitors and therefore had to be replaced by today’s building.[53]

From this spot, in 1744, during the War of the Austrian Succession, the French king Louis XV of France watched the bombing of Freiburg carried out by this troops. A canon that almost hit him, is immured at the Lorettokapelle. A little North-East of it, at the West end, there is a still recognizable former quarry, where stones used for the Freiburg Minster were taken from in the Middle Ages. Further quarries and clay pits can be found at Lorettoberg. Some were already used in the Middle Ages. One remaining clay pit, for example, is the lower Schlierbergweiher. During a detonation in 1896, the hydrophilic layer the clay pit was damaged and it ran full of water, which is why the use of it was abandoned.[54] [55]

The Eastside of the Lorettoberg is loosely built up with houses. “Gründerzeit”-villas, which were built between 1870 and 1914, can be found the most. On the Westside - sometimes called the “Schlierberg” - there is an area even less densely built-up that predominantly originates from the second half of the 20th century. Moreover, hillside vineyards belonging to the Staatlichen Weinbauinstitut Freiburg (Freiburg’s public institute for viticulture ) can be found there. Since recently, the headquarters of the Badischer Landwirtschaftlicher Hautpverband (Baden agricultural association) are in an unusual, multistory, wooden passive house, also called the Haus der Bauern (House of the farmers) [56] , that is located at the Merzhauser street, running along the foot of the mountain.

Several of the numerous villas at the Lorettoberg are houses of students' fraternities. The catholic Loretto hospital is on the Eastside, and on the foot of the mountain there are the Loretto Baths, a open-air swimming pools with a “women’s-bath” that is open only to women and children. The Loretto Baths are probably one of Germany’s last public swimming pools with a separate bath that can be used by women only. From there (at the corner Loretto-/Mercystrasse) the so-called Bergleweg, a footpath, leads up to the chapel. The Way of St.James and the “Zähringer”-trail run on it. Before the ascent, there is the Chalet Widmer on the right, a swiss-style prefabricated house of 1887, which, in that same year, was shown at the upper Rhine’s industrial exhibition [57] and meanwhile is under monumental protection [58]. Further South the “Forstliche Versuchs- und Forschungsanstalt – FVA” (silvicultural research institute) of Baden-Wuerttemberg and the “Waldhaus”, an education- and information center on the subjects of forest and sustainability are located.[59]

At the foot on the southwest end, the Heliotrope designed by the architect Rolf Disch, who also designed the nearby solar-powered village in Freiburg’s district Vauban, can be found.

Miscellaneous[edit]

In the crime story Lorettoberg by Volkmar Braunbehrens two people are murdered in the neighborhood of the villas on the eastern slope of the Lorettoberg.

Translation 3 / Loretto chapel[edit]

Loretto chapel in Freiburg in Breisgau

The Loretto chapel located on the Lorettoberg in Freiburg im Breisgau , is one of many replicas of the Casa santathat is located in the Basilica della Santa Casa,which can be found in Loreto, the Italian pilgrimage destination. The chapel and the building were registered in a book listing regional memorials by Freiburg’s regional council. [60] The Stations of the Cross, located west of the chapel and the Hildatower, which is close to these, also belong to this ensemble. The Hildatower was built in 1886 and is named after the Grand Duchess of Baden, Princess Hilda of Nassau.

Features

Freiburg’s Lorettochapel consists of three small chapels that are consolidated under the same ceiling. The actual Lorettochapel, which is consecrated to Maria, is located in the center. The Josephschapel was attached on the Westside later on. The Annen-and Joachimschapel, which is not open to the public but can still be seen from the chapel in the center, is adjoining on the Eastside. The styles of the chapels range from the Gothic to Renaissance and the Baroque. The bell from 1882, with a weight of 63 kilogram (about 139 pounds), stems from Freiburg’s bell foundry Koch and is tuned in G sharp.

History

The reasons for the construction of the chapel were the heavy fights during the Battle of Freiburg between the Bavarian imperial armada lead by Franz von Mercy, and a French army lead by the Duke of Enghien, towards the end of the Thirty Years’ War. The most intense conflicts, leading to high losses on both sides and unstable fortunes of war, were taking place on August 5th 1644 on the hills of the Schlierberg.

The citizens of Freiburg vowed that, in case of victory, they will build a Laurentian house ("Lauretanisches Haißlein") for the Blessed Virgin, according to the sample of the Basilica della Santa Casa in Loreto, on the same spot where the Josephschapel, which was destroyed during the battles, was located. Indeed, the French withdrew at night toward Breisach, after they lost 6000 men in the battles.

Only in 1657, Christoph Mang, who was guild master of the merchants, and his son Franz Xaver donated the chapel. Following their example, baron Heinrich von Garnier was the one donating the St.-Anna-chapel in 1660 [61]. At the will of the donators, the chapel belonged to the parish of Freiburg's minster and the Guardian of the Capuchin monastery took care of pastoring.

In the following years, the number of people who went on a pilgrimage to the Lorettochapel increased so heavily that in 1785, Freiburg’s aldermen prohibited religious worships in the chapel on Sundays and holidays in order to make believers visit religious masses in their local parishes.

In 1744, during the War of Austrian Succession, another conflict between Austria and France evolved. King Louis XV of France decided to watch the Freiburg’s bombardment from the place in front of the chapel. Despite an agreement between the belligerent parties to not bomb the hill of field commander Louis XV, who in return promised to spare Freiburg's minster from cannonade, yet a canon ball stroke the chapel, however, failing to hit the king. Today, the canon ball can still be seen above the chapel's door.

Even though in 1788 all neighbouring chapels were abolished because of an ordinance made by Joseph II the Holy Roman Emperor, the Loretto chapel, as well as the St.Odile, survived/remained as a consequence of protests from Freiburg’s citizens.

By the end of the 18th century, maintenance work was done to adjust the inside of the chapel to contemporary style. However, these works veneered/daubed the existing paintings, which were made according to the original Loreto-cupper engravings by Johann Caspar Brenzinger (1651-1737). Additionally, the mainenance works were cause for the destruction of many other little artifacts. In 1902, the painter Josef Schultis restored the mural paintings.

The “Bruderhaus” located next to the chapels, already was a destination for tourists during the time when the first maintenance works were done, and over time it developed more and more to be a beer garden and restaurant to visit during a trip. From 1903 until 1905, the restaurant still existing today was built on the fundaments of the “Bruderhaus” and follows the style guidelines of the German renaissance and the art nouveau. It is connected to the chapel via an elevated roofed walkway. Today this restaurant is called the Schloß-Café and is owned by an ecclesiastical charity institution of Breisgau’s catholic religious fund.

Stations of the cross

The 14 sculptures that constitute the stations of the cross at the chapel, were constructed by Freiburg’s sculptor Wilhelm Walliser [62] and were also registered in Freiburg’s book of regional memorials.

Translation 4 / Kommunles Kino Freiburg[edit]

Kommunales Kino Freiburg[edit]

The Kommunales Kino Freiburg is a non-commercial municipal cinema in Freiburg im Breisgau. It was founded in 1972.

History

Freiburg’s Young Socialists in the SPD, a group for social commitment, launched the initiative to establish a municipal cinema in Freiburg.

Eventually, on November 23rd in 1972, the Committee of the Municipal Cinema was founded in the restaurant Feierling in Freiburg. The first film screening was held on January 8th 1973 in rooms of the vocational school located at the Friedrichsring.

In 1981, the Kommunales Kino Freiburg moved into an old train station of the Höllentalbahn in the Wiehre district, together with the Free Artist Group Freiburg. Besides offices and the actual cinema hall, a gallery is also located in the building. In 1981, the café in the old Wiehre trainstation was founded. After the disbanding of the Free Artist Group Freiburg, the Literature Forum in the Southwest moved into the old Wiehre train station in 2003. Since then, this train station is called "house for film and literature". Occasionally, the municipal cinema publishes an film periodical, the “Journal Film”.

Program

Showing other films in other ways – this motto describes the program of Freiburg’s municipal cinema well. Besides classic movies and contemporary films, lots of cooperation with other associations and establishments takes place there as well. In addition to the film program, lectures and introductions on film history and film analysis are given. / In addition to the film program, film historical and film analytical lectures and introductions are given. Experimental avant-garde films, silent movies with live backing, children’s movies, and films of the Cinema of France are shown on a regular basis. Special emphasis is put on the “Wednesday cinema” that presents ethnographic movies alongside films from Asia, Latin-America and Africa and/or with migration background (on Wednesdays).

The Kommunales Kino Freiburg is a venue for the CineLatino (a Latin-American film festival) and for the Brazil Plural festival. Since 1985, it additionally hosts a prestigious ethnographic film festival together with Freiburg’s film forum every other year.

For its program the cinema was awarded the “Kinopreis des Kinematheksverbunds”, a German cinema prize, 6 times already. Most recently it was awarded in 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008 and 2010.

Work Record[edit]

Week 1 (21.10.15)

1. translation of "Ahoy/ Research" - 281 words - 60 min

2. arrange user page, addition of links, references - 20 min

3. proofreading - 30 min

4. problems - "ihrerzeit", "seemännisch", " [...] der erste Bogen mit Einträgen bis zum Stichwort allverein [...] "

Week 2 (28.10.15)

1. translation of "Ahoy/ Early evidence in German original texts" - 376 words - 90 min

2. addition of links, references, picture etc - 5 min

3. proofreading - 15 min

3. problems - "Von 1844 datiert der Schwank Politik an einer Wirthstafel von Friedrich Giehne, bei der die Bedienung eines Wirtshauses mit „Kellner! Ahoi!!“ gerufen wurde." , "Erstaunlich ist der „Landgang“ der Interjektion."

Week 3 (04.11.15)

1. translation of "Ahoy / Early evidence in German original texts and German, usage - 372 words - 50 min

2. addition of links, references, pictures - 10 min

3. proofreading - 20 min

4. problems - „Maritimes“ , der gebundene Seemann, [...] war der Ruf 1859 üblich, übermütig, liefen auf eine Höhe, Segel lichten, [...] küßte einen auf die Nase, old word: Wirthstafel

Week 4 (11.11.15)

1. translation of "Ahoy / USA: Bell's ahoy - beginning" - 334 words - 40 min

2. arrangement of page, addition of links, references, pictures - 10 min

3. proofreading - 20 min

4. problems - "Telefonverkehr", "[...] konkurrierten die beiden Erfinder Alexander Graham Bell und Thomas Alva Edison nicht nur um die Technik der Telefonie, sondern auch um das Wort, mit dem ein Telefonat eröffnet werden sollte." , heiser werden/..dass er heiser wurde, ...

Week 5 (18.11.15)

1. translation of "Ahoy / USA: Bell's ahoy and Reception/Adaption" - 60 min

2. addition of links, references - 15 min

3. proofreading - 15 min

4. problems - "üblich gewordenen" , "Rezeption" passende Übersetzung , "Telefonvermittlung", "[…] als er mit Watson vor Publikum ein Ferngespräch über 143 Meilen Telegrafendraht der Eastern Railroad nach North Conway in New Hampshire mit den Worten eröffnete [...]" > Schachtelsätze, ...

Week 6 (25.11.15)

1. translation of "Ahoy / USA: finished Rezeption and started Unterlegenes ahoy " - 50 min

2. addition of links, references, picture - 20 min

3. proofreading - 15 min

4. problems - Land-und Telefonratten, "... als Formel zu wenig auf Konversation ausgerichtet", ...

Week 7 (02.12.15)

1. translation of "Ahoy / finished Unterlegenes ahoy" and started translation of "Lorettoberg" - 55 min

2. addition of links, references, arrangements - 25 min

3. proofreading - 10 min

4. problems - "Vermittlungsschränke" , "[...] zur Begrüßung", "[...] Hauptrand-Verwerfung des Oberrheingrabens", etc.

Week 8 (09.12.15)

1. translation of "Lorettoberg" / Bauwerke - 65 min

2. addition of links, references - 10 min

3. proofreading - 10 min

4. problems - "...in Freiburg einzog", "Luftbewachung und –beobachtung", ...

Week 9 (16.12.15)

1. translation of "Lorettoberg" / Bauwerke , Sonstiges - 60 min

2. addition of links, references - 15 min

3. proofreading - 10 min

4. problems - “zu den Themen […]” , "Auf der Westseite, der teilweise Schlierberg genannt wird" --> wrong grammar, "Ferner sind dort Rebhänge zu finden, die zum Staatlichen Weinbauinstitut Freiburg gehören, neuerdings in seiner Nachbarschaft an der an seinem Fuße verlaufenden Merzhauser Straße in einem ungewöhnlichen, mehrstöckigen Passivhaus aus Holz auch das Haus der Bauern, die Hauptgeschäftsstelle des Badischen Landwirtschaftlichen Hauptverbandes (BLHV)." --> makes no sense

Week 10 (13.01.16)

1. translation of "Lorettokapelle" - 55 min

2. addition of links, references - 10 min

3. proofreading - 30 min

4. problems - Denkmalbuch, “[…] der westlich gelegene Kreuzweg” , appropriate word for “Ausstattung”, Reichsarmada, Tatsächlich zogen sich die Franzosen nach dem Verlust von 6000 Mann in der Nacht gegen Breisach zurück > since “gegen” is an ambigous term , [...] und schwankendem Kriegsglück [...]“

Week 11 (20.01.16)

1. translation of "Lorettokapelle" - 50 min

2. addition of links, references - 10 min

3. proofreading - 25 min

4. problems - „Gottesdienst“, Trotz einer Absprache der kriegsführenden Parteien, den Feldherrnhügel Louis' XV. nicht zu beschießen [...], "übertünchten", a lot of nominalization in the German text

Week 12 (27.01.16)

1. translation of "Lorettokapelle" - 45 min

2. addition of links, references, picture - 10 min

3. proofreading - 15 min

4. problems - “Bruderhaus”, "[...] sich im Laufe der Zeit immer mehr zu einer Gartenwirtschaft und Ausflugsgaststätte entwickelte."

Week (03.02.16)

1. translation of "Kommunales Kino Freiburg" - 70 min

2. addition of links, weblink, picture - 5 min

3. proofreading - 20 min

4. problems - Arbeitskreis, „Die Initiative [...] ging vom [...] aus.“ Eigennamen wie „Arbeitsgemeinschaft Kommunales Kino“, Freien Künstlergruppe Freiburg, Livebegleitung , correct use of commas

References[edit]

- ^ Johann Gottfried Flügel: Vollständiges Englisch-Deutsches und Deutsch-Englisches Wörterbuch. Teil 1, 3. Aufl. Leipzig 1847, s. v. ahoy, s. v. hoay. Deutsch holla für ahoy hat noch Madame Bernard: German equivalents for english thoughts. London 1858, S. 4.

- ^ Dietmar Bartz: Ahoi! Ein Wort geht um die Welt. In: ders.: Tampen, Pütz und Wanten. Seemannssprache, Wiesbaden 2014, ISBN 978-3-86539-344-9, S. 306

- ^ Jacob und Wilhelm Grimm: Deutsches Wörterbuch. 2. Aufl. Leipzig, Stuttgart 1983ff s. v. ahoi

- ^ Friedrich Kluge: Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache. 23. Aufl. Berlin, New York 1999, ISBN 3-11-016392-6, s. v.

- ^ Dietmar Bartz: Ahoi! Ein Wort geht um die Welt. In: ders.: Tampen, Pütz und Wanten. Seemannssprache, Wiesbaden 2014, ISBN 978-3-86539-344-9, S. 306 f.

- ^ Dietmar Bartz: Ahoi! Ein Wort geht um die Welt. In: ders.: Tampen, Pütz und Wanten. Seemannssprache, Wiesbaden 2014, ISBN 978-3-86539-344-9, S. 308 f.

- ^ Berlin 1846, zitiert nach Jacob und Wilhelm Grimm: Deutsches Wörterbuch. 2. Aufl. Leipzig, Stuttgart 1983ff s. v. ahoi, Zitat in der Schreibweise des Wörterbuchs

- ^ Dietmar Bartz: Ahoi! Ein Wort geht um die Welt. In: ders.: Tampen, Pütz und Wanten. Seemannssprache, Wiesbaden 2014, ISBN 978-3-86539-344-9, S. 309

- ^ Wilhelm Heine: Die Expedition in die Seen von China, Japan und Ochotsk. 2. Band, Leipzig 1859, S. 76

- ^ Wilhelm von Gutzeit: Wörterschatz der Deutschen Sprache Livlands, Band 1; Riga 1864, s. v. ahoi

- ^ Jacob und Wilhelm Grimm: Deutsches Wörterbuch. 2. Aufl. Leipzig, Stuttgart 1983ff s. v. ahoi

- ^ Friedrich Kluge: Seemannssprache. Wortgeschichtliches Handbuch deutscher Schifferausdrücke älterer und neuerer Zeit, Verlag der Buchhandlung des Waisenhauses, Halle a. d. Saale 1908 (Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1911: Hain, Meisenheim 1973, ISBN 3-920307-10-0), s. v. ahoi

- ^ Wolfram Claviez: Seemännisches Wörterbuch. Bielefeld 1973, ISBN 3-7688-0166-7, s. v. ahoi

- ^ Jacob und Wilhelm Grimm: Deutsches Wörterbuch. 2. Aufl. Leipzig, Stuttgart 1983ff s. v. ahoi

- ^ Paul Heyse: San Vigilio. In: Paul Heyse: Gesammelte Werke III; hrsg. von Erich Petzet. 2. Reihe, 2. Band, Stuttgart 1902, S. 603

- ^ Carl Sternheim: Don Juan. Leipzig 1909, S. 175

- ^ Anna Seghers: Aufstand der Fischer von Santa Barbara. Potsdam 1928, S. 51

- ^ Hans Fallada: Wer einmal aus dem Blechnapf frisst. Berlin 1934, zitiert nach Hermann Paul: Deutsches Wörterbuch. 9. Aufl. 1992, ISBN 3-484-10679-4, s. v. ahoi

- ^ Der Prozess um des Esels Schatten, zitiert nach Friedrich Dürrenmatt: 4 Hörspiele. Berlin 1967, S. 28

- ^ Günter Grass: Die Blechtrommel. Berlin 1986, S. 180

- ^ Hermann Kant: Das Impressum. Berlin 1972, S. 103

- ^ Ulrich Plenzdorf: Die neuen Leiden des jungen W. Rostock 1973, S. 81

- ^ James Alexander Mackay: Sounds out of silence. A Life of Alexander Graham Bell. Edinburgh 1997, S. 154

- ^ R. T. Barrett, in: American notes and queries, Bd. 3: 1943–44; S. 76. Einem Zitat bei Barrett zufolge hat Bell Telefonate mit „hoy, hoy“ eröffnet.

- ^ James Alexander Mackay, Sounds out of silence. A Life of Alexander Graham Bell; Edinburgh 1997; S. 128f.

- ^ „More loudly and distinctly than I had ever heard it talk between two rooms, Bell's voice was vibrating from [the telegraph relay], shouting, ‚Ahoy! Ahoy! Are you there? Do you hear me? What is the matter?‘ I could even hear that he was getting hoarse, for he had been shouting all the time I had been hunting over the factory building. I ahoyed back and I could hear his sigh of relief as he asked me, „Where have you been all the time?“ Catherine MacKenzie: The man who contracted space. Boston 1928, S. 146.

- ^ Catherine MacKenzie: The man who contracted space. Boston 1928, S. 149

- ^ Catherine MacKenzie: The man who contracted space. Boston 1928, S. 153

- ^ Catherine MacKenzie: The man who contracted space. Boston 1928, S. 153

- ^ „Believe it or not, you were supposed to say ‚ahoy hoy‘ when answering the phone in the early days“, deutsch etwa: „Kaum zu glauben, früher sollte man ‚ahoy hoy‘ sagen, wenn man ans Telefon ging“; Cecil Adams: More of the straight dope. New York 1988, S. 468

- ^ Allen Koenigsberg, in: All Things Considered. Sendung des National Public Radio vom 19. März 1999, Exzerpt, aufgerufen am 20. Mai 2008

- ^ Joseph Nathan Kane: Famous first facts. A record of first happenings, discoveries and inventions. 1. Aufl. New York 1933, zitiert nach der 3. Aufl. New York 1964, S. 600, dort unter Verweis auf den Telephone Almanac von AT&T ohne weitere Angaben

- ^ William Safire: You could look it up. More on language. New York 1988, S. 139

- ^ „American ship ahoy!“ came the voice. […] „Hello!“ yelled back Captain Hawks, and I could hear laughter in his tone, the laughter of pleasure.“ Oswald Kendall: The Romance of the Martin Connor. New York 1916, S. 218

- ^ The Simpsons Archive, Website mit Suchmaschine, aufgerufen am 18. November 2008

- ^ Archive copy at the Wayback Machine. Wie Bell 1876 seinen Mitarbeiter Watson rief Burns seinen Vertrauten Smithers: „Smithers, come here, I want you.“ Archive copy at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Charles Nicol: Buzzwords and Dorophonemes. How Words Proliferate and Things Decay in Ada. In: Gavriel Shapiro: Nabokov at Cornell. Ithaca, N.Y. 2003, S. 98, dazu ein Kommentar, aufgerufen am 18. November 2008, Annotations 83.24–84.03

- ^ Joseph A. Conlin: The American Past. A survey of American history. Fort Worth 2002, S. 522

- ^ Aussage von Frederick Perry Fish, ab 1901 Präsident von AT&T, ohne Angabe des Zeitpunktes. Francis Jehl: Menlo Park Reminiscences. Dearborn, Michigan 1937, Band 1, S. 133, zitiert nach Allen Koenigsberg: Archive copy at the Wayback Machine In: Antique Phonograph Monthly. Jahrgang 8, 1987, Nr. 6, Teil 1

- ^ Allen Koenigsberg, in: All Things Considered. Sendung des National Public Radio vom 19. März 1999, Exzerpt, aufgerufen am 20. Mai 2008

- ^ William Safire: You could look it up. More on language. New York 1988, S. 139

- ^ Dietmar Bartz: Wie das Ahoj nach Böhmen kam. In: mare, Die Zeitschrift der Meere. Heft 21, 2000, S. 33–37

- ^ The boys attending the switches become expert and rarely make mistakes, although it is difficult to see how anything could be done correctly amid the din and clamor of twenty or thirty strong voices crying ‚Hello! hello, A!‘ ‚Hello, B!‘, in: Scientific American. 10. Januar 1880, S. 21, zitiert nach den Online-Revisionen des OED auf www.oed.com, de facto seine 3. Auflage, eine gebührenpflichtige, in Bibliotheken aufrufbare Webseite, s. v. hello, aufgerufen am 20. Mai 2008. Der beschriebene Ort war die Merchant’s Telephone Exchange in New York City, vgl. American Notes & Queries. A Journal for the Curious, Bd. 3; 1943–44; S. 44

- ^ Allen Koenigsberg: Archive copy at the Wayback Machine In: Antique Phonograph Monthly. Jg. 8, 1987, Nr. 6, Teil 2; zu den Datierungen: New York Times, 5. März 1992, online, aufgerufen am 18. November 2008

- ^ Mark Twain. "A Connecticut Yankee In King Arthur’s Court". Archived from the original on 2012-04-09. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- ^ Kartendienste des Bundesamtes für Naturschutz (Hinweise)

- ^ Deutschlandviewer auf onmaps.de (Maßstab 1:500)

- ^ Karlheinz Scherfling: Die Erde bebt immer wieder – auch im Schwarzwald. In: Der Schwarzwald 1/2005. Schwarzwaldverein, 2005, abgerufen am 13. Juni 2013 (PDF; 4,3 MB).

- ^ Hildaturm - Öffnungszeiten und Bauzeichnung auf hildaturm.de

- ^ Friedrich Kempf: Oeffentliche Brunnen und Denkmäler. In: Badischer Architecten- und Ingenieur-Verein, Oberrheinischer Bezirk (Hrsg.): Freiburg im Breisgau. Die Stadt und ihre Bauten. H. M. Poppen & Sohn, Freiburg im Breisgau 1898, S. 496 (Scan bei Wikisource).

- ^ Peter Kalchthaler, badische-zeitung.de: Der Hildaturm auf dem Lorettoberg. Badische Zeitung, 1. Oktober 2012

- ^ lexikon-der-wehrmacht.de: Kampfgeschwader 51 „Edelweiß“

- ^ Schloss-Cafe Lorettoberg auf badische-seiten.de

- ^ Schlierbergweiher, Schlierbergweiher, Projekt Bachpatenschaften der Stadt Freiburg, abgerufen am 28. Oktober 2014.

- ^ Unterer Schlierbergweiher, Badische Seiten, abgerufen am 28. Oktober 2014.

- ^ Simone Lutz: badische-zeitung.de: "Haus der Bauern": Vornehmes aus Holz und Glas. Badische Zeitung, 18. Mai 2014

- ^ Badischer Architecten- und Ingenieur-Verein, Oberrheinischer Bezirk (Hrsg.): Privat-Bauten. In: Freiburg im Breisgau. Die Stadt und ihre Bauten. H. M. Poppen & Sohn, Freiburg im Breisgau 1898, S. 642 (Scan bei Wikisource).

- ^ Freiburg: 1000 Jahre Wiehre: 20 Assoziationen – Stadtgespräch fudder. Abgerufen am 13. Juni 2013.

- ^ waldhaus-freiburg.de

- ^ Badische Zeitung vom 26. November 2008, abgerufen am 4. Dezember 2012

- ^ Hermann Kopf: Christoph Anton Graf von Schauenburg (1717–1787): Aufstieg und Sturz des breisgauischen Kreishauptmanns, Rombach, Freiburg im Breisgau 2000, ISBN 3-7930-0343-4, S. 11

- ^ Michael Klant: Vergessene Bildhauer. In: Skulptur in Freiburg. Kunst des 19. Jahrhunderts im öffentlichen Raum, Freiburg 2000, S. 164–172 ISBN 3-922675-77-8, S. 168