Valmer Castle

The Château de Valmer is a complex located northeast of Chançay, a French commune in the Indre-et-Loire department of the Centre-Val de Loire region. It was built in 1524 by remodeling a medieval castle of the Binet family and was renovated and expanded in the second half of the 17th century. After numerous other changes and repairs during the 19th and 20th centuries, the main building was almost destroyed by a fire in 1948.

The remains of the neo-Renaissance style complex are among the many châteaux in the Loire Valley and, together with the associated terraced baroque garden, have been listed as a monument historique since 1 May 1930.[1] The park and garden have been designated a Jardin remarquable since 2004.[2] They can be explored for a fee together with the castle chapel carved into the rock, which 12,000 visitors visit every year.[3]

History[edit]

Valmer was first mentioned in 1434. At that time, it was owned by Catherine de Bueil, who was the first known owner of the domain. On 23 July 1461, Jacques Binet bought it.[4] In 1500, his son Macé was listed as the owner. From his marriage to Jeanne Briçonnet came the son Jean, Maître dʼhôtel to the King and Queen of Navarre. Between 1524 and 1529[5] he had the medieval castle that had existed until then extensively changed and made into a more livable residence. At the same time, a castle chapel was hewn into the tuff rock on which the château stands, on 28 November 1529, by the Bishop of Autun consecrated and consecrated on 13 March 1535.[6] When the castle was looted by Protestant soldiers during the Huguenot Wars in 1562 it belonged to Jean Coustely, the mayor of Tours. The looters did not hesitate to torture Jean's daughter and burn the soles of her feet in order to get hold of the family's suspected money in a hiding place on the castle grounds.

Jean's descendant, Claude Coustely, sold Valmer on 23 May 1640, to an advisor to Louis XIII, Thomas Bonneau, who made extensive remodeling and additions to the complex. The interiors were reworked in the Louis XIII style and, to the northeast of the building, Bonneau had a pavilion built in the same style from 1646 to 1647[5] to house the palace administrator. Because the new lord of the château found the old rock chapel too dark and damp, a new chapel was built on the west side of the steward's house called Petit Valmer, which was blessed on 25 October 1647.[4] To the south, Bonneau also had new farm buildings built and the gate erected as an entrance to the grounds. The present gardens and park also date back to Thomas Bonneau. Although there had already been an associated terraced garden since the first château from the 16th century, modeled on Italian Renaissance gardens, Bonneau had them reworked in the Baroque manner and additionally created the upper terrace (Haute terrasse in French).[2] He placed numerous vases and statues in the newly-designed gardens and park. One known from him is a white marble statue commissioned by from the sculptor Jacques Sarazin, depicting Leda and Zeus (as a swan), and has been in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York since 1980.[7]

After the death of Thomas Bonneau, the estate passed through numerous hands and never belonged to one owner for long. In 1691, Etienne-Dominique Chaufourneau was recorded as the owner, but by 1703,[7] Valmer belonged to Gatien Pinon. In 1736, the property was up for sale again and was purchased by M. Duvelaer, the commander of the port of Lorient,[7] before being bought ten years later by Nicolas Chaban de La Rivière on 5 July 1746. His descendants remained owners until 1888. He increased the property's value by buying the neighboring seigneurie, La Côte, on 17 April 1756.[4] On his death in 1763, he left the château and its land to his sister Marie Chaban and her husband, Jacques Valleteau de Chabrefy, who bequeathed it to their son, Baron Thomas Valleteau de Chabrefy,[5][7] in 1766. After his death in May 1792, the château passed to his widow, Marie-Françoise Barré.[8] On 4 August 1810, the Seigneurie La Côte was again divided from the estate and given to Jérôme, Marie-Françoise's younger son.[4] The elder son, Thomas II, was to inherit Valmer in return, which happened in November 1825.[9] Thomas II had the frescoes in the younger castle chapel restored in 1826, as evidenced by his coat of arms cartouche in the chapel. He may also have had the tall Doric column in the center of the hornbeam labyrinth, which is still preserved today, and numerous vases placed in the garden.[9] They probably come from the Château de Chanteloup, which was dismantled and sold piece by piece in 1823.[9]

When Thomas II died in January 1846,[9] his son Jérôme-Charles Valleteau de Chabrefy succeeded him as the owner of the château. He had the estate modernized and changed in the Neo-Renaissance style from June 1847. For this purpose, he hired the well-known architect Félix Duban, who had made a name for himself with the restoration of Château de Blois, which had begun four years earlier. However, it is not known what exactly Duban proposed in terms of redesign and whether it was implemented. Because his bill was very low, researchers assume that his share in the changes was very small.[10]

Duban's pupil, Jules Potier de la Morandière, played a much greater role in the remodeling, and numerous alterations were carried out according to his plans in the period from 1855 to 1856. With the exception of the northeast side, all the façades were radically altered by, among other things, removing the mullioned windows and replacing the Renaissance-style dormer windows. The main portal on the southwest side facing the main courtyard was redesigned, as was the northwest side, where la Morandière had a two-story gallery inserted between two corner towers. In addition, a low, one-story kitchen wing was added to the main building on the southeast side. The changes did not only extend to the main château but also included farm buildings and outbuildings. For example, the old mill located 450 m (1,480 ft) northwest of the château building was demolished in 1855, and in its place, accommodations for the leaseholder of the farmyard and a new barn were built.[11]

On Jérôme-Charles' death in 1874, the estate passed to his three children from his marriage to Marie Amélie de Bonnard: Jérôme, Henriette and Marguerite. They sold Valmer in September 1888[4] to Paul Lefèvre, a stockbroker from Paris. Only seven months after the purchase, Lefèvre hired the architect Léon-Auguste Brey to redesign the northeast façade of the main building, which had remained unchanged until 1889. In addition, before 1902,[12] the upper floor of the gallery on the northwest side was replaced by a loggia with round arches and Doric columns. Around the period from 1890 to 1900,[13] Lefèvre also had the rock chapel redesigned. Some of the garden vases were given away by him around 1900 and are now at the Château de Pierrefitte in Auzouer-en-Touraine.

In return, he purchased other vases and also purchased columns to place in the château garden and had two greenhouses built.[12] After his death in 1925, the château was occupied by his widow and his daughter Renée and her husband, Adhémar Barré de Saint-Venant, when, on the night of 20 October 1948, a fire broke out in the main building because of a forgotten iron. Only a few parts of the building were not destroyed by the fire, including the basement, two staircases, the loggia and the kitchen wing. The main château stood as an unsecured fire ruin for 20 years before the remains were finally demolished in August 1968. In 1949, there was a plan to rebuild a part of the château to house a retirement home, but this was not realized. Only the kitchen wing, called the "orangery", was restored by the architect Maurice Boillé. The work was only one of a total of four renovations carried out during the 20th century.[5]

The current[when?] owners of the château, Aymar de Saint-Venant, a great-grandson of Paul Lefèvre, and his wife Alix, maintain the extensive gardens and have opened them to visitors. In addition, together with their son Jean, they cultivate the vineyards belonging to the cV and rent out the orangerey for parties and receptions.

Description[edit]

Château de Valmer is located in the valley of the Brenne River on a slope on the eastern bank of the river. The architecture, including terraced gardens and a park, presents itself to the visitor as a typical ensemble of the 16th and 17th centuries.

Architecture[edit]

Main building[edit]

The location of the former main château is marked today by yew trees cut into shape. It was located in the center of the axis of the complex, which ran from southwest to northeast. The two floors of the rectangular building were covered by a hipped roof. At three of the corners stood three-story square towers. The five-aisle southwest side facing the main courtyard was designed as a show façade. Above the centrally located main entrance was a niche with statues, crowned by a round-arched gable. The attic hatches on this side had shell-shaped pediments, while the hatches on the northeastern long side of the building had richly sculpted pediments of a different shape. The façade there, after changes at the end of the 19th century, also had cross-bar windows. Between the two corner towers on the northwest side stood a two-story gallery building, whose windows on the first floor were framed by pilasters. The upper floor was designed as a loggia. Its three round arches were supported by Doric columns, between which there was a parapet. The building was covered by a high-hipped roof. Until the 19th century, a drawbridge led from the southeast side of the first floor to the upper terrace of the garden.[7]

On the ground floor of the main building, in addition to two living rooms, a staircase, an office and a large kitchen, there was a room called Grand Salon whose central ceiling painting was attributed to the painter François Lemoyne.[14][15] It was surrounded by corner medallions in the grisaille technique]]. The library had a painted wooden beam ceiling and a fireplace that showed a portrait of the French King Henry IV. This fireplace was undamaged in the 1948 fire and Count Saint-Venant subsequently sold it; it was later installed in a château in Normandy.[16] Another remarkable fireplace stood in the dining room. It had been assembled from old stone fragments from the 15th and 16th centuries and installed there in the mid-19th century. Among the few pieces spared from the fire was a lintel made of tufa from the northeast facade of the main château. It shows a stag's head in full relief and is now attached to the fireplace in the orangery. On the first floor, there were six living rooms and some utility rooms, and in the attic, there were also various smaller rooms.

Petit Valmer and Chapel of the Rock[edit]

Built in 1647, the Petit Valmer is the residence of the current château owners. The one-story pavilion building has a slate-covered hipped roof. On its northwestern side is the former castle chapel,[4] which was still in use until 1890. Its interior decoration is still preserved, including frescoes with scenes from the life of Christ and the Assumption of the Virgin Mary. The paintings were restored in 1935.[17]

A two-nave chapel was cut into the tufa rock on which the upper garden terrace is located in the first half of the 16th century. Access to its interior is by a basket-arched entrance, above which there is a niche with the statuette of St. Roch and a neo-Gothic keel arch. However, this design is not from the same period as the chapel but dates to the end of the 19th century. Each chapel nave has a shallow two-bay ribbed vault, with the nave extended by a small altar niche. Inside there is an altar whose mense is decorated on the front by a relief in the form of a triptych. It shows a Pietà in the center, framed on the sides by the portraits and coats of arms of the two donors. They are Jean Bernard, Archbishop of Tours from 1441 to 1466, and his nephew Guy. The relief originally came from the archbishop's summer residence in Vernou-sur-Brenne and was placed on the altar under Paul Lefèvre. He also had the two windows with stained glass from the 16th century installed in the chapel. Two small side chapels on the long sides of the naves contain a Romanesque baptismal font and a colorfully painted stone statue of St. Martin from the 1530s.[7] The figure was restored in 2012. A large clay tablet with an inscription commemorates the founding and blessing of the chapel in 1529.

Farm buildings[edit]

The farm buildings of the château are grouped on three sides around a small courtyard in the southern corner of the château grounds. The three buildings on the northwestern side of the courtyard were horse stables, accommodations for coachmen and grooms and a wine press. All of them have a granary in the attic and separate the farmyard from one of the garden terraces. On the southwest side, facing the street, is a massive round tower with a flat conical roof. It used to be a dovecote and, with 1,339 nesting holes inside,[7] it was designed for about 3,000 birds. Other buildings that belonged to the château economy were a dairy, a coach house, a bakehouse, cow and pig stables, sheds and a kennel for the pack of hunting dogs.[14] The curious thing about the farm buildings is that their roof sides facing the main building are covered with expensive slate, while the sides facing away from the château have a covering of cheaper red tiles.

Château park and garden[edit]

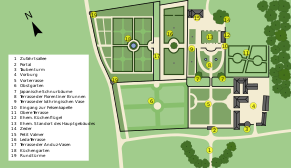

The park and garden belonging to the château are completely enclosed by a wall with two round towers on the northwest side. An approximately 450 metres (1,480 ft)-long[18] avenue planted with horse chestnuts leads from the southwest to the château and opens in a semicircle in front of a large rusticated portal with a lattice gate and a broken triangular gable. Behind it begins the terraced garden, which was laid out along two axes in the 17th century. The first runs as an extension of the avenue from southwest to northeast; after the entrance gate it crosses the front terrace flanked by three outbuildings (Terrasse des devants), crosses the almost 15 metres (49 ft)[6] wide dry moat by means of a three-arched stone bridge, to finally end after the Florentine fountains terrace (Terrasse des fontaines florentines) and the former château site in the forest park. The second axis begins in the southeast and ends in the northwest. It overcomes eight different height levels and a height difference of 30 metres (98 ft).[19] It starts on an embankment with yew trees and hibiscus bushes and continues across the Upper Terrace (Haute terrasse) and the Florentine Fountains Terrace, crosses the Terrace of the Lorraine Vase (Terrasse du vase de Lorraine) and the Leda Terrace (Terrasse de Leda) to reach, via a staircase, the Terrace of the Anduz Vases (Terrasse des vases dʼAnduz) and finally, after crossing the kitchen garden, ends on the other side of a street at the Grand Canal, which is fed by the Brenne.

Terrace garden[edit]

The five-hectare[20] terraced garden was inspired by Italian Renaissance gardens when it was laid out, but later underwent a transformation into a typical Baroque garden, and today it has more or less the same appearance it had in 1695. The individual terraces, separated by low walls, brick parapets and stairs, have names that result from their shape and decoration.

On the "Upper Terrace", closed by a parapet, there is a labyrinth of topiary hornbeams. In its center stands a tall, slender column with a vase at its upper end, originally from the Château de Chanteloup. From there, on may reach the terrace of the "Florentine Fountains", so-called from the two Italian model fountains that are placed there. They each have three water bowls and are crowned by a bronze putto.[1] The terrace planting consists of Armand's woodland vines, very old peonies, wisteria, Roses of the Pierre de Ronsard variety, pink- and white-flowered nicotiana plants, as well as sage, dahlias and dog chamomile. On the southwestern edge of the terrace are two large Japanese string trees. Their long branches reach down into the moat. Together with an ancient cedar,[21] they are among the three remarkable specimen trees in the palace garden.

The dry moat of the castle once again forms a small garden in itself. It is accessible from the Leda Terrace via a spiral staircase[6] carved into the rock in the 15th century. Growing there, among other things, are different kinds of hydrangeas and valerian. Tall shrubs cut into shapes imitate buttresses.

The west terrace is bordered on its west side by the Lorraine Vase Terrace and lies on one level with it. Southwest of the Fountain Terrace, separated from it by the deep dry moat, lies the symmetrically designed Front Terrace. It forms a kind of forecourt divided by straight paths into four quadrangles. Northwest of it is an orchard, also symmetrically designed.

A staircase leads from the Lorraine Vase Terrace to the lower Leda Terrace. It is named after a marble statue formerly placed in it, made by the sculptor Jacques Sarazin. It has since been replaced by a statue of a male figure. On the terrace, there are mainly white-flowered plants, such as the rose varieties Avon and Marie Pavié and Myrtofolio cherry laurel. At the foot of the wall, overgrown with Chasselas vines, are irises, lavender and magnificent candles.

A double-flight staircase[6] from the 18th century with two large stone lion statues at the top leads to another level, 6 metres (20 ft) lower,[6] where the Anduz Vases Terrace is located. Their planting is determined mainly by yews cut into shape and Chinese lagerstromias of the "Summer Evening" variety. Holy herbs and rosemary reinforce the Mediterranean impression of this garden.

Another staircase on the west side leads to the kitchen garden,[22] which is located a little lower once again and covers an area of one hectare, where over 900 plants are cultivated, including old and almost forgotten species. It is laid out according to the classical principle of the 15th century and divided by two straight paths into four carrels surrounded by box hedges, which in turn are divided into four other parts. At the intersection of the paths lined with plum and peach trees in the center of the garden is a large water basin with a fountain. In addition to peaches and plums, the garden grows other types of fruit such as nectarines, nashi pears, apricots, figs, apples and pears. One of the planting quadrangles is reserved for plants with small fruits such as gooseberries, currants and raspberries. A special feature is a 100 metres (330 ft)-long pergola overgrown with various pumpkin plants.[23] In the kitchen garden, however, not only useful plants are cultivated; ornamental plants such as geraniums and sack flowers also grow on the eastern wall of this area. On the bounding west wall of the kitchen garden are two round towers with conical roofs, which today serve as storage facilities. In the past, they were the accommodations for gardeners and were also used as donkey stables.[6]

Forest Park[edit]

North and west of the Petit Valmer is a 60-hectare forest park that has managed to preserve its 17th-century appearance.[6] Its trees are mostly oaks and hornbeams, with chestnuts and wild cherries. Numerous straight forest paths, which radiate through the park, offer the possibility of a walk in the forest. At the crossing points, there are columns similar to those on the Upper Terrace of the château garden. A recently[when?] established arboretum with rare trees and shrubs completes the selection of plants in the park. Two old buildings have been preserved in the park: a small pavilion called "Vide-bouteille", with a folded tent roof, and a viewing platform called Belvedere, supported by three arches made of brick, which used to be used to observe the hunting activity in the forest.[14]

Wine growing[edit]

Aymar de Saint-Venant and his son Jean cultivate 28 hectares of vines. Six hectares of this are within the walled château grounds. In doing so, they are continuing an old family tradition, since viticulture in the château domain is documented as early as 1888. As is generally the case in the Vouvray winegrowing region, the Chenin blanc grape variety is grown for a white wine of the AOC Vouvray and Grolleau for a rosé of the Touraine appellation.[24]

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Jardin d'agrément et parc du château de Valmer" (in French). Ministry of Culture. Archived from the original on 11 September 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ^ a b "PARC ET JARDINS DU CHÂTEAU DE VALMER (85 ha) - Indre-et-Loire". Comité des Parcs et Jardins de France. Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- ^ "Les 7 Sites Patrimoniaux" [The 7 Heritage Sites] (PDF). Destination Val de Loire-Amboise (in French). Office de Tourisme Val d'Amboise. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "Le domaine et son histoire" (in French). Château de Valmer. Archived from the original on 16 March 2023. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d L. Vieira (2001). "Deux architectes célèbres au château de Valmer, à Chancay : F. Duban et J. de la Morandière (1847-1856)". Bulletin de la Société Archéologique de Touraine (in French). XLIIIX: 153.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Les jardins". Château de Valmer. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Guillaume Métayer (4 August 2013). "Chançay: Le Château de Valmer". Reugny-Neuillé. Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ^ Nicolas Viton de Saint-Allais: Annuaire historique, généalogique et héraldique de l'ancienne noblesse de France. Paris. 1835. p. 142.

- ^ a b c d L. Vieira (2001). "Deux architectes célèbres au château de Valmer, à Chancay : F. Duban et J. de la Morandière (1847-1856)". Bulletin de la Société Archéologique de Touraine (in French). XLIIIX: 153.

- ^ L. Vieira (2001). "Deux architectes célèbres au château de Valmer, à Chancay : F. Duban et J. de la Morandière (1847-1856)". Bulletin de la Société Archéologique de Touraine (in French). XLIIIX: 155.

- ^ L. Vieira (2001). "Deux architectes célèbres au château de Valmer, à Chancay : F. Duban et J. de la Morandière (1847-1856)". Bulletin de la Société Archéologique de Touraine (in French). XLIIIX: 160.

- ^ a b L. Vieira (2001). "Deux architectes célèbres au château de Valmer, à Chancay : F. Duban et J. de la Morandière (1847-1856)". Bulletin de la Société Archéologique de Touraine (in French). XLIIIX: 160.

- ^ L. Vieira (2001). "Deux architectes célèbres au château de Valmer, à Chancay : F. Duban et J. de la Morandière (1847-1856)". Bulletin de la Société Archéologique de Touraine (in French). XLIIIX: 165.

- ^ a b c Guillaume Métayer (9 September 2013). "Chançay: "Belle et bonne terre à vendre", Valmer en 1736". Reugny-Neuillé (in French). Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- ^ Guillaume Métayer (13 August 2013). "Chançay : Le Château de Valmer". Reugny-Neuillé (in French). Archived from the original on 18 January 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ^ L. Vieira (2001). "Deux architectes célèbres au château de Valmer, à Chancay : F. Duban et J. de la Morandière (1847-1856)". Bulletin de la Société Archéologique de Touraine (in French). XLIIIX: 159.

- ^ L. Vieira (2001). "Deux architectes célèbres au château de Valmer, à Chancay : F. Duban et J. de la Morandière (1847-1856)". Bulletin de la Société Archéologique de Touraine (in French). XLIIIX: 154.

- ^ According to the cadastral map available online at geoportail.gouv.fr

- ^ C. Bibollet; R. de Laroche (2003). Châteaux, Parcs et Jardins en vallée de la Loire (in French). p. 171.

- ^ "Valmer, des jardins inspirés de la Renaissance Italienne" [Valmer, gardens inspired by the Italian Renaissance]. Le Jardinoscope (in French). 4 October 2010. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- ^ Chateaux of the Loire. Green Guides. Michelin Travel Partner UK Limited. 2015. p. 162. ISBN 9782067203532.

- ^ J.-B. Leroux; C. Grive (2009). Fasteux châteaux de la Loire. p. 50.

- ^ "Château de Valmer". Gardenvisit. Archived from the original on 30 November 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ^ "Le vignoble". Château de Valmer. Archived from the original on 16 March 2023. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

Further reading[edit]

- Catherine Bibollet; Robert de Laroche (2003). Châteaux, Parcs et Jardins en Vallée de la Loire. Tournai: La Renaissance du Livre. pp. 169–173. ISBN 2-8046-0754-2.

- Josyane Cassaigne; Alain Cassaigne (2007). 365 Châteaux de France. Geneva: Aubanel. pp. 346–347. ISBN 978-2-7006-0517-4.

- Jean-Baptiste Leroux; Catherine Grive (2009). Fasteux chateaux de la Loire. Paris: Déclic. pp. 47–51. ISBN 978-2-84768-173-4.

- Xavier Mathias; Alix de Saint Venant. Le potager d'Alix de Saint Venant au Château de Valmer. Paris: Le Chêne.

- Jean de Montarnal (1934). Château et manoirs de France. Vol. 3. Paris: Vincent & Fréal. pp. 7–14.

- André Montoux (1979). Old Logis de Touraine. Vol. 4. Chambray-lès-Tours: CLD. pp. 21–27.

- L. Vieira (2001). "Deux architectes célèbres au château de Valmer, à Chancay : F. Duban et J. de la Morandière (1847-1856)". Bulletin de la Société Archéologique de Touraine (in French). XLIIIX: 153–167. ISSN 1153-2521 – via Gallica.

- Ludovic Vieira (2001). "L'incendie du Château de Valmer, à Chancay". Rivières tourangelles (in French). Monts: Société d'étude de la rivière Indre et de ses affluents: 61–67.

External links[edit]

- Château website

- Base Mérimee: Château de Valmer Jardin d'agrément et parc du château de Valmer

- Terrace garden videos on YouTube: