Affair of Porto Novo

| Affair of Porto Novo | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

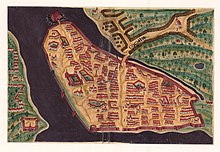

Painting of the ship Ulrica Eleonora, 1719 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

40–50 men 1 ship |

100–700 men 2 ships | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Several captured | Unknown | ||||||||

The Affair of Porto Novo, also called the Porto Novo incident,[1] was a successful Anglo–French attack and destruction of the newly founded Swedish factory at Porto Novo (modern Parangipettai) in Southern India on 20 October 1733.

The English governor at Madras, George Morton Pitt, had been alerted to the newly established Swedish factory at Porto Novo, and after failing to convince the Nawab to prevent the Swedes there from conducting trade, contacted Pierre Le Noir, the French governor of Pondicherry. After making an agreement, they sent a force of several hundred men led by Captain de la Faralle down the coast towards Porto Novo and attacked the warehouse, with the Swedes surrendering a day after the attack.

Background

[edit]Foundation of the SOIC

[edit]

On 14 June 1731, after the collapse of the Ostend Company, the SOIC received its charter.[2] The government granted the company permission to trade "with all places east of the Cape of Good Hope" which initiated its first octroi. After its establishment, the company aroused a lot of opposition in Sweden, as despite the long-distance shipping and direct purchases "from the source" aligned with the mercantilist principles, the planned import of foreign manufactured and luxury goods was hard to reconcile with.[3]

Moreover, the company faced competition from major foreign companies, and the suspicion was that it was merely a disguised continuation of the Ostend Company.[3]

Arrival at Porto Novo

[edit]In January 1733, the Ulrica Eleonora, a renamed English ship under the command of Petter von Utfall, left Göteborg. Its destination was India, where they intended on finding any possible business in the region.[4]

Upon the Ulrica Eleonora's arrival at Porto Novo in September,[5] the officers onboard immediately began negotiations with agents from the Mughal Emperor. Their intention was to establish a Swedish factory there, in other words a station with a magazine and office for continued trade in the East Indies.[4] The Swedes were welcomed, promised the protection of the Nawab, and were allowed to unload a majority of their cargo into a warehouse.[6]

After a month, when the monsoon came, Petter von Utfall decided it was best for the Ulrica Eleonora to sail towards Bengal for refitting during the winter instead taking a planned trip to China, and to leave some people behind in Porto Novo to open up trade.[7][4] Several members of the crew, Charles Barrington, Thomson, Thomas Combes, and the writer, along with 36 others remained in Porto Novo to protect the warehouse and conduct trade with the goods already accumulated.[6] Other sources claim there were some 50 men left in Porto Novo.[4]

Prelude

[edit]For a month, the merchants at Porto Novo remained there undisturbed, and trading continued. However, Thomson heard a rumour that George Morton Pitt, the Governor of Madras, "designs to play the devil with us; but I hope their boastings will not frighten any of our friends or the concerned, for we are not apprehensive of anything they can do to us."[6]

Anglo–French preparation

[edit]

When news of the Swedish presence reached Governor Pitt in Madras, he wished to end the Swedish trade in the region and attempted to convince the Nawab to put a stop to it.[4] However, the Nawab refused, and Pitt subsequently decided to act independently. He contacted Governor Pierre Le Noir of Pondicherry, seeking help. Le Noir strongly disapproved of the Swedish expedition and agreed to militarily support the British.[8] He wrote to Pitt: "We are entirely of opinion that such interlopers must cause a great deal of trouble and loss to our Companies."[9] After being notified of the Swedish presence, Le Noir and his council prohibited the residents and merchants in Pondicherry to trade with Porto Novo, and when seven men of the Ulrica Eleonora defected to Pondicherry, Le Noir refused to hand them over to Captain Petter von Utfall.[10][11]

Affair

[edit]The governors assembled a force; estimates vary from around 100,[12] several hundred[10][4] to 200,[13] 600,[14] or 700 men.[8] This force, led by Captain de la Farelle, sailed down the coast towards Porto Novo and subsequently landed there. Despite the town being in Mughal territory, where neither the British nor French had territorial rights, they attacked the warehouse on 20 October,[5] seizing the cargo, along with the Ulrica Eleonora's papers and took them to Fort St. David.[10][7][4] After only a day after the attack, the remaining Swedes gave up.[4]

Thomson, Combes, and several others were captured and sent to Fort St. David. However, Charles Barrington, who the British were more eager to catch, managed to escape alongside some people, taking refuge in Danish Tranquebar.[15][10][12] In Tranquebar, Barrington sent the first account of the "violence commited at Porto Novo" back home and eventually managed to return to Sweden, leaving the Swedish sailors who made up the guard in Porto Novo to join British service in Madras, who had no other means to sustain themselves. After the attack, only two Swedes remained in Porto Novo: Dr. Munck and Anthony Bengsten.[10]

After the seizure, the staff from both the French and English companies investigated the confiscated books, letters, and other papers. After reading the documents, they claimed that they found proof of the illegitimacy of the SOIC in the instructions for the ship, therefore, taking control of the factory and seizing the ship would serve as a warning against pursuing illicit trade in the East Indies.[16]

Attack on the Ulrica Eleonora

[edit]During the Anglo-French attack, the Ulrica Eleonora had remained in Bengal, where its men and officers were well received. During Christmas time in 1733, Utfall had heard rumours of what had happened.[4] In early 1734, the Ulrica Eleonora headed back to Porto Novo in order to collect her cargo after being refitted for the home voyage to Sweden. However, when she arrived in early March and about to anchor, two vessels in the roadstead fired warning shots at her.[17][10][4]

These ships had been dispatched by the Governors, one French and one British with each holding a hundred men, in anticipation of the Ulrica Eleonora's return. The British troops were commanded by Major Roach, and the British ship, the Prince Augustus, was commanded by Captain Gostlin.[10]

Seeing that an attempted landing would result in a disaster, Captain Petter von Utfall once again put to sea, sailing southwards. The French and British ships pursued Utfall closely for some 15 hours, managing to keep the Ulrica Eleonora within firing range. Eventually, they abandoned the chase and left her to continue her journey, without most of her cargo, a large portion of her crew, and nearly all of the supercargoes.[18]

Aftermath

[edit]

Following her repulsion from Porto Novo, the Ulrica Eleonora went around southern India and later proceeded along the Malabar Coast towards the town of Cochin, with the intention to collect water. However, the Dutch authorities in the town not only declined to give them any water, but also detained a certain Ouchterlony and 13 other men who had accompanied him ashore with him after a short fight where two men were killed,[19] in order to make the Ulrica Eleonora continue her journey now with a far smaller crew.[20] Further attempts to dock at other Dutch ports ended just as badly.[4]

The Swedish situation was critical, as the remaining water and food was slowly running out, and the winds were pulling the ship westwards.[4] To her luck, the Ulrica Elenora, once it came near Mauritius, came across a French vessel that was "a-fishing for turtle" which was manned by a more friendly crew than any of the British or French who the Swedes encountered in India. After meeting, the Ulrica Eleonora was finally given the water they desperately needed, and her crew bought supplies at a high cost on the island, along with fifteen Lascars joining the voyage.[21] The Swedes were also allowed to stay there for seven months to regain their strength and repair the ship.[4]

In February, the Ulrica Eleonora finally arrived back in Europe, with only 35 members of her original crew.[22][23]

References

[edit]- ^ Hodacs 2020, p. 575.

- ^ Ivarsson 2022, p. 9.

- ^ a b Boëthius, Bertil. "Colin Campbell". sok.riksarkivet.se. National Archives of Sweden. Retrieved 2024-12-20.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Frängsmyr 1976, p. 26.

- ^ a b "1431-1432 (Nordisk familjebok / Uggleupplagan. 21. Papua - Posselt)". runeberg.org (in Swedish). 1915. Retrieved 2024-12-19.

- ^ a b c Gill 1958, p. 52.

- ^ a b Banerji 1967, p. 76.

- ^ a b Hellstenius 1860, p. 11.

- ^ Gill 1958, pp. 52–53.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gill 1958, p. 53.

- ^ Dalgliesh 1933, p. 196.

- ^ a b Dickson, Parmentier & Ohlmeyer 2007, p. 155.

- ^ Lannoy & Linden 1938, p. 38.

- ^ Simons, Christin (2021-01-21). "The law is open on both sides: Great Britain and Sweden's Interpretation of the Law of Nations in the East India Trade in the 1730s". www.kcl.ac.uk. London: King's College London. Retrieved 2024-12-19.

- ^ Ivarsson 2022, p. 41.

- ^ Ivarsson 2022, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Dickson, Parmentier & Ohlmeyer 2007, pp. 155–156.

- ^ Gill 1958, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Banerji 1967, p. 77.

- ^ Gill 1958, p. 54.

- ^ Gill 1958, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Gill 1958, p. 55.

- ^ Dickson, Parmentier & Ohlmeyer 2007, p. 156.

Works cited

[edit]- Banerji, R.N. (1967). "Early Swedish Trade Relation with India". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 29. Indian History Congress: 74–82. JSTOR 44137998.

- Dalgliesh, Wilbert Harold (1933). The Perpetual Company of the Indies in the Days of Dupleix. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Dickson, David; Parmentier, Jan; Ohlmeyer, Jane H. (2007). Irish and Scottish Mercantile Networks in Europe and Overseas in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Academica Press. ISBN 9789038210223.

- Frängsmyr, Tore (1976). Ostindiska kompaniet: människorna, äventyret och den ekonomiska drömmen [East India Company: the people, the adventure and the financial dream] (in Swedish). Bokförlaget Bra Böcker. ISBN 9789170246531.

- Gill, Conrad (1958). "The Affair of Porto Novo: An Incident in Anglo-Swedish Relations". The English Historical Review. 73 (286). Oxford University Press: 47–65. doi:10.1093/ehr/LXXIII.286.47. JSTOR 558969.

- Hellstenius, John (1860). Bidrag till Svenska Ost-Indiska Compagniets Historia: 1731-1766. Edquist.

- Hodacs, Hanna (2020). "Keeping It in the Family: The Swedish East India Company and the Irvine Family, 1731–1770". Journal of World History. 31 (3). University of Hawaiʻi Press: 567–596. doi:10.1353/jwh.2020.0032. JSTOR 27106169.

- Ivarsson, Elin (2022). "Finding One's Place in a Global Market: Chartered Companies, Masculinities, and the Porto Novo Affair" (PDF). Uppsala University.

- Lannoy, Charles de; Linden, Herman Vander (1938). A History of Swedish Colonial Expansion. Translated by Brinton, George Elder; Reed, Henry Clay. University of Delaware Press.