Bagyidaw

| Bagyidaw Sagaing Min ဘကြီးတော် | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| King of Konbaung, Prince of Sagaing, Sagaing King, Royal Uncle | |||||

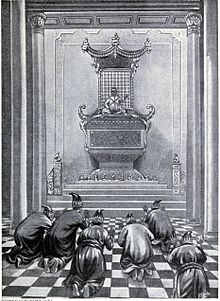

A British depiction of Bagyidaw purportedly ordering to wrest Bengal from the British | |||||

| King of Burma | |||||

| Reign | 5 June 1819 – 15 April 1837 | ||||

| Coronation | 7 June 1819 | ||||

| Predecessor | Bodawpaya | ||||

| Successor | Tharrawaddy | ||||

| Born | Maung Sein (မောင်စိန်) 23 July 1784 Amarapura | ||||

| Died | 15 October 1846 (aged 62) Amarapura | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Consort | Hsinbyume Nanmadaw Me Nu | ||||

| Issue | 5 sons, 5 daughters, including Setkya Mintha | ||||

| |||||

| House | Konbaung | ||||

| Father | Thado Minsaw | ||||

| Mother | Min Kye, Princess of Taungdwin | ||||

| Religion | Theravada Buddhism | ||||

Bagyidaw (Burmese: ဘကြီးတော်, pronounced [ba̰dʑídɔ̀]; also known as Sagaing Min, [zəɡáiɰ̃ mɪ́ɰ̃]; 23 July 1784 – 15 October 1846) was the seventh king of the Konbaung dynasty of Burma from 1819 until his abdication in 1837. Prince of Sagaing, as he was commonly known in his day, was selected as crown prince by his grandfather King Bodawpaya in 1808, and became king in 1819 after Bodawpaya's death. Bagyidaw moved the capital from Amarapura back to Ava in 1823.

Bagyidaw's reign saw the First Anglo-Burmese War (1824–1826), which marked the beginning of the decline of the Konbaung dynasty. He inherited the largest Burmese empire, second only to King Bayinnaung's, but also one that shared ill-defined borders with British India. In the years leading to the war, the king had been forced to suppress British supported rebellions in his grandfather's western acquisitions (Arakan, Manipur and Assam), but unable to stem cross border raids from British territories and protectorates.[1] His ill-advised decision to allow the Burmese army to pursue the rebels along the vaguely defined borders led to the war. The longest and most expensive war in British Indian history[2] ended decisively in British favor, and the Burmese had to accept British terms without discussion.[3] Bagyidaw was forced to cede all of his grandfather's western acquisitions, and Tenasserim to the British, and pay a large indemnity of one million pounds sterling, leaving the country crippled for years.

Devastated, Bagyidaw held out hope for some years that Tenasserim would be returned to him, and paid the balance of indemnity in 1832 at great sacrifice.[4] The British redrew the border with Manipur in 1830, but by 1833, it was clear the British would not return any of the former territories. The king became a recluse, and power devolved to his queen Nanmadaw Me Nu and her brother.[5] His brother Crown Prince Tharrawaddy raised a rebellion in February 1837, and Bagyidaw was forced to abdicate the throne in April 1837. King Tharrawaddy executed Queen Me Nu and her brother but placed his brother under house arrest. Bagyidaw died in October 1846 at age 62.[4]

Early life

[edit]The future king was born Maung Sein to Crown Prince Thado Minsaw, Prince of Shwedaung and his half-sister Min Kye, Princess of Taungdwin, on 23 July 1784. The infant prince was granted Sagaing as his fief by his grandfather King Bodawpaya, hence known as Prince of Sagaing. On 23 June 1793, the young prince, not yet 9, was made a general of the Northern and Southern Corps of Royal Cavalry. On 9 February 1803, the 18-year-old prince married 14-year-old Princess Hsinbyume, a granddaughter of Bodawpaya. The young prince was fond of shows, theater, elephant catching and boat racing.[2]

Crown Prince

[edit]His father Crown Prince Thado Minsaw died on 9 April 1808. Nine days later, the young prince at 23 was suddenly elevated to the position of Crown Prince by his grandfather King Bodawpaya. The prince was also allowed to inherit his father's fiefs of Dabayin and Shwedaung. The Crown Prince was Master-General of the Ordnance in the Burmese-Siamese War of 1808, which ended in a stalemate. His elevation to crown prince also brought his royal servants, including Maung Yit (later Gen. Maha Bandula) of Dabayin and Maung Sa (later Lord of Myawaddy) of Sagaing to prominence. Myawaddy became his longtime adviser and personal secretary (atwinwn) until his abdication in 1837. He promoted Maung Yit to governor of Ahlon-Monywa.

In 1812, his first queen Princess Hsinbyume died of childbirth in Mingun near Ava. The crown prince built a beautiful white stupa in memory of his first wife named Myatheindan Pagoda at Mingun.[6] He took on five more queens as crown prince (of the eventual number of 23 queens). His third and later chief queen Nanmadaw Me Nu built the Maha Aungmye Bonzan Monastery in 1818, more commonly known as Me Nu Ok Kyaung (Me Nu's Brick Monastery), unusual in that Burmese monasteries traditionally are wooden structures.[7]

During his stay as crown prince, his grandfather Bodawpaya renewed his expansionism in the west. In February 1814, a Burmese expeditionary force invaded Manipur, placing Marjit Singh, who grew up in Ava, as vassal king.

In 1816, the Ahom governor of Guwahati in Assam, Badan Chandra Borphukan visited the court of Bodawpaya to seek help in order to defeat his political rival Purnananda Burhagohain, the Prime Minister of Ahom Kingdom in Assam. A strong force of 16,000 under the command of Gen. Maha Minhla Minkhaung was sent with Badan Chandra Borphukan. The Burmese force entered Assam in January 1817 and defeated the Assamese force in the battle of Ghiladhari. Meanwhile, Purnananda Burhagohain died and Ruchinath Burhagohain, the son of Purnananda Burahgohain fled to Guwahati. The reigning Ahom king Chandrakanta Singha came in terms with Badan Chandra Borphukan and his Burmese allies. He appointed Badan Chandra Borphukan as Mantri Phukan (Prime Minister). An Ahom princess Hemo Aideo was given for marriage to Burmese King Bodawpaya along with many gifts to strengthen the ties with the Burmese monarch. The Burmese force returned to Burma soon after. A year later, Badan Chandra Borphukan was assassinated and the Ahom king Chandrakanta Singha was deposed by rival political faction led by Ruchinath Burhagohain, the son of Purnananda Burhagohain. Chandrakanta Singha and the friends of Badan Chandra Borphukan appeal for help to Bodawpaya. In February 1819, the Burmese forces invaded Assam for second time and reinstalled Chandrakanta Singha on the throne of Assam.[8][9]

Reign

[edit]Troubles on the western front

[edit]Bodawpaya died on 5 June 1819, and Bagyidaw ascended to the throne without opposition. On 7 June 1819, he was crowned at Amarapura with the reign name of Sri Pawara Suriya Dharmaraja Maharajadhiraja. It was later expanded to Siri Tribhawanaditya Dhipati Pawara Pandita Mahadhammarajadhiraja.[10] Bagyidaw inherited the second largest Burmese empire but also one that shared a long vaguely defined borders with British India. The British, disturbed by the Burmese control of Manipur and Assam which threatened their own influence on the eastern borders of British India, supported rebellions in the region.[1]

The first to test Bagyidaw's rule was the Raja of Manipur, who was put on the Manipuri throne only six years earlier by the Burmese. Raja Marjit Singh failed to attend Bagyidaw's coronation ceremony, or send an embassy bearing tributes, as all vassal kings had an obligation to do. In October 1819, Bagyidaw sent an expeditionary force of 25,000 soldiers and 3,000 cavalry led by his favorite general Maha Bandula to reclaim Manipur.[11] Bandula reconquered Manipur but the raja escaped to neighboring Cachar, which was ruled by his brother Chourjit Singh.[12] The Singh brothers continued to raid Manipur using their bases from Cachar and Jaintia, which had been declared as British protectorates.

The instabilities spread to Assam in 1821, when the Ahom king of Assam, Chandrakanta Singha tried to shake off Burmese influence. He hired mercenaries from Bengal and began to strengthen the army. He also began to construct fortification to prevent further Burmese invasion.[13] Bagyidaw again turned to Bandula. It took Bandula's 20,000-strong army about a year a half, until July 1822, to finish off the Assamese army. Bagyidaw now scrapped the six- century-old Assamese monarchy and made Assam a province under a military governor-general. This differs with the Assamese versions of history where it is written that Bagyidaw installed Jogeswar Singha, a brother of Hemo Aideo, the Ahom princess who was married to Bodawpaya as the new Ahom king of Assam and a military governor-general was appointed to look after the administration.[14][15] The defeated Assamese king fled to British territory of Bengal. The British ignored Burmese demands to surrender the fugitive king, and instead sent reinforcement units to frontier forts.[16] Despite their success in the open battlefield, the Burmese continued to have trouble with cross border raids by rebels from British protectorates of Cachar and Jaintia into Manipur and Assam, and those from British Bengal into Arakan.

At Bagyidaw's court, the war party which included Gen. Bandula, Queen Me Nu and her brother, the lord of Salin, made the case to Bagyidaw that a decisive victory could allow Ava to consolidate its gains in its new western empire in Arakan, Manipur, Assam, Cachar and Jaintia, as well as take over eastern Bengal.[17] In January 1824, Bandula allowed one of his top lieutenants, Maha Uzana, into Cachar and Jaintia to chase away the rebels. The British sent in their own force to meet the Burmese in Cachar, resulting in the first clashes between the two. The war formally broke out on 5 March 1824, following border clashes in Arakan.

War with the British East India Company

[edit]In the beginning of the war, battle-hardened Burmese forces, who were more familiar with the terrain which represented "a formidable obstacle to the march of a European force", were able to push back better armed British forces made up of European and Indian soldiers.[18] By May, Uzana's forces had overrun Cachar and Jaintia, and Lord of Myawaddy's forces had defeated the British inside Bengal, causing a great panic in Calcutta.

Instead of fighting in harsh terrain, the British took the fight to the Burmese mainland. On 11 May, a British naval force of over 10,000 men, led by Archibald Campbell entered the port city of Yangon, taking the Burmese by surprise.[18] Bagyidaw ordered Bandula and most of the troops back home to meet the enemy at Yangon. In December 1824, Bandula's 30,000 strong force tried to retake Yangon but was soundly defeated by the much better armed British forces. The British immediately went on an offensive on all fronts. By April 1825, the British had driven out the Burmese forces from Arakan, Assam, Manipur, Tenasserim, and the Irrawaddy delta where Gen. Bandula died in action. After Bandula's death, the Burmese fought on but their last-ditch effort to retake the delta was repulsed in November 1825. In February 1826, with the British army only 50 miles away from Ava, Bagyidaw agreed to British terms.

As per the Treaty of Yandabo, the British demanded and the Burmese agreed to:[18]

- Cede to the British Assam, Manipur, Arakan, and Tenasserim coast south of Salween river,

- Cease all interference in Cachar and Jaintia,

- Pay an indemnity of one million pounds sterling in four installments,

- Allow for an exchange of diplomatic representatives between Ava and Calcutta,

- Sign a commercial treaty in due course.

After the war

[edit]

The treaty imposed highly severe financial burden to the Burmese kingdom, and effectively left it crippled. The British terms in the negotiations were strongly influenced by the heavy cost in lives and money which the war had entailed. Some 40,000 British and Indians troops had been involved of whom 15,000 had been killed. The cost to the British India's finances had been almost ruinous, amounting to approximately 13 million pounds sterling. The cost of war contributed to a severe economic crisis in India, which by 1833 had bankrupted the Bengal agency houses and cost the British East India Company its remaining privileges, including the monopoly of trade to China.[19]

For the Burmese, the treaty was a total humiliation and a long-lasting financial burden. A whole generation of men had been wiped out in battlefield. The world the Burmese knew of conquest and martial pride, built on the back of impressive military success of prior 75 years, had come crashing down. An uninvited British Resident in Ava was a daily reminder of humiliation of defeat.[19] The burden of indemnity would leave the royal treasury bankrupt for years. The indemnity of one million pounds sterling would have been considered a colossal sum even in Europe of that time, and it became frightening when translated to Burmese kyat equivalent of 10 million. The cost of living of the average villager in Upper Burma in 1826 was one kyat per month.[20]

Bagyidaw could not come to terms with the loss of the territories, and the British used Tenasserim as bait for the Burmese to pay the installments of indemnity. In 1830, the British agreed to redraw the Manipuri border with Burma, giving back Kabaw Valley to the Burmese. Bagyidaw delivered the balance of the indemnity at great sacrifice in November 1832. But by 1833, it was clear that the British had no intention of returning any of the territories. The king, who used to love theater and boat racing, grew increasingly reclusive, afflicted by bouts of depression. The palace power devolved to his chief queen Me Nu and her brother Maung O. In February 1837, Bagyidaw's crown prince and brother Tharrawaddy rebelled, and two months later in April, Bagyidaw was forced to abdicate. Tharrawaddy executed Me Nu and her brother, and kept his brother under house arrest. Bagyidaw died on 15 October 1846, at age 62. The former king had 23 queens, five sons and five daughters.

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Owen 2005: 87–88

- ^ a b Myint-U 2006: 112–113

- ^ Phayre 1883: 237

- ^ a b Htin Aung 1967: 220–221

- ^ Steinberg et al 1987: 106

- ^ Sladen 1868

- ^ Cooler Chapter 4

- ^ E. A. Gait 1926 A History of Assam: 225–227

- ^ Dr. S.K. Bhuyan 1968 Tungkhungia Buranji or A History of Assam(1681–1826) : 197–203

- ^ Yi Yi 1965: 53

- ^ Aung Than Tun 2003

- ^ Phayre 1883: 233–234

- ^ Dr. S. K. Bhuyan 1968 Tungkhungia Buranji or A History of Assam (1681–1826) : 204–205

- ^ Dr. S. K. Bhuyan 1968 Tungkhungia Buranji or A History of Assam (1681–1826): 206–207

- ^ E. A. Gait 1926 A History of Assam: 228–230

- ^ Shakespear 1914: 62–63

- ^ Myint-U 2001: 18–19

- ^ a b c Phayre 1883: 236–237

- ^ a b Webster 1998:142–145

- ^ Htin Aung 1967: 214–215

References

[edit]- Aung Than Tun (Monywa) (2003-03-26). "Maha Bandula, Immortal Myanmar Supreme Commander". The New Light of Myanmar.

- Bhuyan, S.K. (1968). Tungkhungia Buranji or A History of Assam (1681–1826). Guwahati: THE GOVERNMENT OF ASSAM IN THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORICAL AND ANTIQUARIAN STUDIES IN ASSAM.

- Charney, Michael W. (2006). Powerful Learning: Buddhist Literati and the Throne in Burma's Last Dynasty, 1752–1885. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan.

- Cooler, Richard M. "The Art and Culture of Burma: The Konbaung Period – Amarapura". Northern Illinois University. Archived from the original on 14 March 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- Gait, Sir Edward (1926). A History of Assam. Calcutta: Thacker, Spink & Co.

- Harvey, G. E. (1925). History of Burma: From the Earliest Times to 10 March 1824. London: Frank Cass & Co. Ltd.

- Htin Aung, Maung (1967). A History of Burma. New York and London: Cambridge University Press.

- Lieberman, Victor B. (2003). Strange Parallels: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c. 800–1830, volume 1, Integration on the Mainland. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80496-7.

- Maung Maung Tin (1905). Konbaung Hset Maha Yazawin (in Burmese). Vol. 1–3 (2004 ed.). Yangon: Department of Universities History Research, University of Yangon.

- Myint-U, Thant (2001). The Making of Modern Burma. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79914-0.

- Myint-U, Thant (2006). The River of Lost Footsteps—Histories of Burma. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-16342-6.

- Owen, Norman G. (2005). The Emergence of Modern South-East Asia: A New History. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2841-7.

- Phayre, Lt. Gen. Sir Arthur P. (1883). History of Burma (1967 ed.). London: Susil Gupta.

- Shakespear, Leslie Waterfield (1914). History of Upper Assam, Upper Burmah and northeastern frontier. Macmillan.

- Sladen, Edward. "Colonel Sladen's Account of Hsinbyume Pagoda at Mingun, 1868" (PDF). SOAS. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 April 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- Steinberg, David Joel (1987). David Joel Steinberg (ed.). In Search of South-East Asia. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Webster, Anthony (1998). Gentlemen Capitalists: British Imperialism in South East Asia, 1770–1890. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-171-8.

- Yi Yi, Ma (1965). "Burmese Sources for the History of the Konbaung Period 1752–1885". Journal of Southeast Asian History. 6 (1). Cambridge University Press on behalf of Department of History, National University of Singapore: 48–66. doi:10.1017/S0217781100002477. JSTOR 20067536.

External links

[edit]- Journal of An Embassy from the Governor-General of India to the Court of Ava in the year 1827 by John Crawfurd, 1829

- Journal of An Embassy from the Governor-General of India to the Court of Ava by John Crawfurd, Vol II 1834

- Was "Yadza" Really Ro(d)gers? at the Wayback Machine (archived September 27, 2007) Gerry Abbott, SOAS, Autumn 2005