Enigma Variations

Edward Elgar composed his Variations on an Original Theme, Op. 36, popularly known as the Enigma Variations,[a] between October 1898 and February 1899. It is an orchestral work comprising fourteen variations on an original theme.

Elgar dedicated the work "to my friends pictured within", each variation being a musical sketch of one of his circle of close acquaintances (see musical cryptogram). Those portrayed include Elgar's wife Alice, his friend and publisher Augustus J. Jaeger and Elgar himself. In a programme note for a performance in 1911 Elgar wrote:

This work, commenced in a spirit of humour & continued in deep seriousness, contains sketches of the composer's friends. It may be understood that these personages comment or reflect on the original theme & each one attempts a solution of the Enigma, for so the theme is called. The sketches are not 'portraits' but each variation contains a distinct idea founded on some particular personality or perhaps on some incident known only to two people. This is the basis of the composition, but the work may be listened to as a 'piece of music' apart from any extraneous consideration.[b]

In naming his theme "Enigma", Elgar posed a challenge which has generated much speculation but has never been conclusively answered. The Enigma is widely believed to involve a hidden melody.[citation needed]

After its 1899 London premiere the Variations achieved immediate popularity and established Elgar's international reputation.

History

[edit]Elgar described how on the evening of 21 October 1898, after a tiring day's teaching, he sat down at the piano. A melody he played caught the attention of his wife and he began to improvise variations on it in styles which reflected the character of some of his friends. These improvisations, expanded and orchestrated, became the Enigma Variations.[1] Elgar considered including variations portraying Arthur Sullivan and Hubert Parry, but was unable to assimilate their musical styles without pastiche and dropped the idea.[2]

The piece was finished on 18 February 1899 and published by Novello & Co. It was first performed at St James's Hall in London on 19 June 1899, conducted by Hans Richter. Critics were at first irritated by the layer of mystification, but most praised the substance, structure and orchestration of the work. Elgar later revised the final variation, adding 96 new bars and an organ part. The new version (which is usually played today) was first heard at the Worcester Three Choirs Festival on 13 September 1899, with Elgar conducting.[3]

The European continental premiere was performed in Düsseldorf, Germany on 7 February 1901, under Julius Buths (who would also conduct the German premiere of The Dream of Gerontius in December 1901).[4] The work quickly achieved many international performances, from Saint Petersburg, where it delighted Alexander Glazunov and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov in 1904, to New York, where Gustav Mahler conducted it in 1910.[5]

Orchestration

[edit]The work is scored for an orchestra consisting of 2 flutes (one doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets in B♭, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns in F, 3 trumpets in F, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, side drum, triangle, bass drum, cymbals, organ (ad lib) and strings.

Structure

[edit]

The theme is followed by 14 variations. The variations spring from the theme's melodic, harmonic and rhythmic elements, and the extended fourteenth variation forms a grand finale.

Elgar dedicated the piece to "my friends pictured within" and in the score each variation is prefaced the initials, name or nickname of the friend depicted. As was common with painted portraits of the time, Elgar's musical portraits depict their subjects at two levels. Each movement conveys a general impression of its subject's personality. In addition, many of them contain a musical reference to a specific characteristic or event, such as a laugh, a habit of speech or a memorable conversation. The sections of the work are as follows.

Theme (Enigma: Andante)

[edit]The unusual melodic contours of the G minor opening theme convey a sense of searching introspection:

A switch to the major key introduces a flowing motif which briefly lightens the mood before the first theme returns, now accompanied by a sustained bass line and emotionally charged counterpoints.

In a programme note for a 1912 performance of his setting of Arthur O'Shaughnessy's ode The Music Makers, Elgar wrote of this theme (which he quoted in the later work), "it expressed when written (in 1898) my sense of the loneliness of the artist as described in the first six lines of the Ode, and to me, it still embodies that sense."[6]

Elgar's personal identification with the theme is evidenced by his use of its opening phrase (which matches the rhythm and inflection of his name) as a signature in letters to friends.[7]

The theme leads into Variation I without a pause.

Variation I (L'istesso tempo) "C.A.E."

[edit]Caroline Alice Elgar, Elgar's wife. The variation repeats a four-note melodic fragment which Elgar reportedly whistled when arriving home to his wife. After Alice's death, Elgar wrote, "The variation is really a prolongation of the theme with what I wished to be romantic and delicate additions; those who knew C.A.E. will understand this reference to one whose life was a romantic and delicate inspiration."

(In these notes Elgar's words are quoted from his posthumous publication My Friends Pictured Within which draws on the notes he provided for the Aeolian Company's 1929 pianola rolls edition of the Variations.)

Variation II (Allegro) "H.D.S-P."

[edit]Hew David Steuart-Powell. Elgar wrote, "Hew David Steuart-Powell was a well-known amateur pianist and a great player of chamber music. He was associated with B.G.N. (cello) and the composer (violin) for many years in this playing. His characteristic diatonic run over the keys before beginning to play is here humorously travestied in the semiquaver passages; these should suggest a Toccata, but chromatic beyond H.D.S-P.'s liking."

![\relative c'' { \clef treble \key g \minor \time 3/8 \tempo "Allegro." r16 g-.]\p_"stacc." d'-.[ gis,-.] cis-.[ a-.] | c!-.[ a-.] bes-.[ g!-.] es-.[ c!-.] | cis-. d-. }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/p/7/p7v3ejqoeed9kdrgyp1ayyew2035uy2/p7v3ejqo.png)

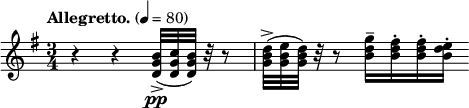

Variation III (Allegretto) "R.B.T."

[edit]Richard Baxter Townshend, Oxford don and author of the Tenderfoot series of books; brother-in-law of the W.M.B. depicted in Variation IV. This variation references R.B.T's presentation of an old man in some amateur theatricals ‒ the low voice flying off occasionally into "soprano" timbre.

Variation IV (Allegro di molto) "W.M.B."

[edit]William Meath Baker, squire of Hasfield, Gloucestershire and benefactor of several public buildings in Fenton, Stoke-on-Trent, brother-in-law of R.B.T. depicted in Variation III, and (step) uncle of Dora Penny in Variation X. He "expressed himself somewhat energetically". This is the shortest of the variations.

Variation V (Moderato) "R.P.A."

[edit]Richard Penrose Arnold, the son of the poet Matthew Arnold, and an amateur pianist. This variation leads into the next without pause.

Variation VI (Andantino) "Ysobel"

[edit]Isabel Fitton, a viola pupil of Elgar. Elgar explained, "It may be noticed that the opening bar, a phrase made use of throughout the variation, is an 'exercise' for crossing the strings – a difficulty for beginners; on this is built a pensive and, for a moment, romantic movement."

Variation VII (Presto) "Troyte"

[edit]Arthur Troyte Griffith, a Malvern architect and one of Elgar's firmest friends. The variation, with a time signature of 1

1, good-naturedly mimics his enthusiastic incompetence on the piano. It may also refer to an occasion when Griffith and Elgar were out walking and got caught in a thunderstorm. The pair took refuge in the house of Winifred and Florence Norbury (Sherridge, Leigh Sinton, near Malvern), to which the next variation refers.

Variation VIII (Allegretto) "W.N."

[edit]Winifred Norbury, one of the secretaries of the Worcester Philharmonic Society. "Really suggested by an eighteenth-century house. The gracious personalities of the ladies are sedately shown. W.N. was more connected with the music than others of the family, and her initials head the movement; to justify this position a little suggestion of a characteristic laugh is given."

This variation is linked to the next by a single note held by the first violins.

Variation IX (Adagio) "Nimrod"

[edit]The name of the variation refers to Augustus J. Jaeger, who was employed as a music editor by the London publisher Novello & Co. He was a close friend of Elgar's, giving him useful advice but also severe criticism, something Elgar greatly appreciated. Elgar later related how Jaeger had encouraged him as an artist and had stimulated him to continue composing despite setbacks. Nimrod is described in the Old Testament as "a mighty hunter before the Lord", Jäger (which can also be spelt Jaeger) being German for hunter.

In 1904 Elgar told Dora Penny ("Dorabella") that this variation is not really a portrait, but "the story of something that happened".[8] Once, when Elgar had been very depressed and was about to give it all up and write no more music, Jaeger had visited him and encouraged him to continue composing. He referred to Ludwig van Beethoven, who had a lot of worries, but wrote more and more beautiful music. "And that is what you must do", Jaeger said, and he sang the theme of the second movement of Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 8 Pathétique. Elgar disclosed to Dora that the opening bars of "Nimrod" were made to suggest that theme. "Can't you hear it at the beginning? Only a hint, not a quotation."

This variation has become popular in its own right and is sometimes used at British funerals, memorial services, and other solemn occasions. It is always played at the Cenotaph, Whitehall in London at the National Service of Remembrance. A version was also played during the Hong Kong handover ceremony in 1997, at the opening ceremony of the London 2012 Olympic Games, and during the 2022 BBC Proms after the season was cut short due to the death of Queen Elizabeth II. The "Nimrod" variation was the final orchestral composition (before the national anthem) played by the Greek National Orchestra in a televised June 2013 concert, before the 75-year-old Athenian ensemble was dissolved in the wake of severe government cutbacks to televised programming.[9]

An adaptation of the piece appears at the ending of the 2017 film Dunkirk in the score by Hans Zimmer.[10][11]

Variation X (Intermezzo: Allegretto) "Dorabella"

[edit]Dora Penny, a friend whose stutter is gently parodied by the woodwinds. Dora, later Mrs. Richard Powell, was the daughter of the Revd (later Canon) Alfred Penny. Her stepmother was the sister of William Meath Baker, the subject of Variation IV. She was the recipient of another of Elgar's enigmas, the so-called Dorabella Cipher. She described the "Friends Pictured Within" and "The Enigma" in two chapters of her book Edward Elgar, Memories of a Variation. This variation features a melody for solo viola.

Variation XI (Allegro di molto) "G.R.S."

[edit]George Robertson Sinclair, the energetic organist of Hereford Cathedral. In the words of Elgar: "The variation, however, has nothing to do with organs or cathedrals, or, except remotely, with G.R.S. The first few bars were suggested by his great bulldog, Dan (a well-known character) falling down the steep bank into the River Wye (bar 1); his paddling upstream to find a landing place (bars 2 and 3); and his rejoicing bark on landing (second half of bar 5). G.R.S. said, 'Set that to music'. I did; here it is."[12]

Variation XII (Andante) "B.G.N."

[edit]Basil George Nevinson, an accomplished amateur cellist who played chamber music with Elgar. The variation is introduced and concluded by a solo cello. This variation leads into the next without pause.

Variation XIII (Romanza: Moderato) " * * * "

[edit]Possibly, Lady Mary Lygon of Madresfield Court near Malvern, a sponsor of a local music festival. "The asterisks take the place of the name of a lady[c] who was, at the time of the composition, on a sea voyage. The drums suggest the distant throb of the engines of a liner, over which the clarinet quotes a phrase from Mendelssohn's Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage."

If it is Lady Mary, Elgar may have withheld her initials because of superstition surrounding the number 13,[13] or he may have felt uneasy about publicly associating the name of a prominent local figure with music that had taken on a powerful emotional intensity.[14] There is credible evidence to support the view that the variation's atmosphere of brooding melancholy and its subtitle "Romanza" are tokens of a covert tribute to another woman, the name most frequently mentioned in this connection being that of Helen Weaver, who had broken off her engagement to Elgar in 1884 before sailing out of his life forever aboard a ship bound for New Zealand.[15][16][17][18][19]

Variation XIV (Finale: Allegro) "E.D.U."

[edit]Elgar himself, nicknamed Edu by his wife, from the German Eduard. The themes from two variations are echoed: "Nimrod" and "C.A.E.", referring to Jaeger and Elgar's wife Alice, "two great influences on the life and art of the composer", as Elgar wrote in 1927. Elgar called these references "entirely fitting to the intention of the piece".[20]

The original version of this variation is nearly 100 bars shorter than the one now usually played. In July 1899, one month after the original version was finished Jaeger urged Elgar to make the variation a little longer. After some cajoling Elgar agreed, and also added an organ part. The new version was played for the first time at the Worcester Three Choirs Festival, with Elgar himself conducting, on 13 September 1899.[3]

Final inscription

[edit]At the end of the full score he inscribed the words "Bramo assai, poco spero, nulla chieggio". This is a quote from Torquato Tasso's Jerusalem Delivered, Book II, Stanza 16 (1595), albeit slightly altered from third to first person. It means: "I long for much, I hope for little, I ask nothing". Like Elgar's own name, this sentence too can be fitted easily into the Enigma theme.[21]

Arrangements

[edit]Arrangements of the Variations include:

- The composer's arrangement of the complete work for piano solo

- The composer's arrangement of the complete work for piano duet (two pianos)

- Duet (piano, four hands) – by John E. West F.R.A.M., F.R.C.O (1863–1929), organist, composer and musical adviser to Novello & Co

- Transcription for chamber ensemble/orchestra by George Morton (UK)[22]

- Brass band – by composer Eric Ball

- There are many arrangements of individual variations, particularly Variation IX "Nimrod"

- Variation X "Dorabella" was published separately in its orchestral version

- Transcription for Wind Band by Earl Slocum (USA)

- Transcription for Symphonic Wind Band by John Morrison (UK)

- Transcription for Symphonic Band by Douglas McLain

- Transcription for the Wanamaker Organ by Peter Richard Conte

- 2013 – Transcription for Symphonic Wind Ensemble by Donald C. Patterson for the United States Marine Band

- 2017 – Hans Zimmer included themes from Elgar's Variations in the soundtrack for the original motion picture soundtrack Dunkirk.

The Enigma

[edit]The word "Enigma", serving as a title for the theme of the Variations, was added to the score at a late stage, after the manuscript had been delivered to the publisher. Despite a series of hints provided by Elgar, the precise nature of the implied puzzle remains unknown.

Confirmation that Enigma is the name of the theme is provided by Elgar's 1911 programme note ("... Enigma, for so the theme is called")[b] and in a letter to Jaeger dated 30 June 1899 he associates this name specifically with what he calls the "principal motive" – the G minor theme heard in the work's opening bars, which (perhaps significantly) is terminated by a double bar.[23] Whatever the nature of the attendant puzzle, it is likely to be closely connected with this "Enigma theme".

Elgar's first public pronouncement on the Enigma appeared in Charles A. Barry's programme note for the first performance of the Variations:

The Enigma I will not explain – its "dark saying" must be left unguessed, and I warn you that the connexion between the Variations and the Theme is often of the slightest texture; further, through and over the whole set another and larger theme "goes", but is not played . . . . So the principal Theme never appears, even as in some late dramas – eg Maeterlinck's L'Intruse and Les sept Princesses – the chief character is never on the stage.[24]

Far from clarifying matters, this utterance seems to envelop the Enigma in further mysteries. The phrase "dark saying" can be read straightforwardly as an archaic synonym for enigma but might equally plausibly be interpreted as a cryptic clue, while the word "further" seems to suggest that the "larger theme" is distinct from the Enigma, forming a separate component of the puzzle.

Elgar provided another clue in an interview he gave in October 1900 to the editor of the Musical Times, F. G. Edwards, who reported:

Mr Elgar tells us that the heading Enigma is justified by the fact that it is possible to add another phrase, which is quite familiar, above the original theme that he has written. What that theme is no one knows except the composer. Thereby hangs the Enigma.[25]

Five years later, Robert John Buckley stated in his biography of Elgar (written with the composer's close cooperation):[26] "The theme is a counterpoint on some well-known melody which is never heard."[27]

Attempted solutions to the Enigma commonly propose a well-known melody which is claimed to be either a counterpoint to Elgar's theme or in some other way linked to it. Musical solutions of this sort are supported by Dora Penny and Carice Elgar's testimony that the solution was generally understood to involve a tune,[28] and by the evidence from an anecdote describing how Elgar encoded the solution in a numbered sequence of piano keys.[29][30] A rival school of thought holds that the "larger theme" which "goes" "through and over the whole set" is an abstract idea rather than a musical theme. The interpretation placed on the "larger theme" forms the basis of the grouping of solutions in the summary that follows.

Julian Rushton has suggested that any solution should satisfy five criteria: a "dark saying" must be involved; the theme "is not played"; the theme should be "well known" (as Elgar stated multiple times); it should explain Elgar's remark that Dora Penny should have been, "of all people", the one to solve the Enigma;[28] and fifthly, some musical observations in the notes Elgar provided to accompany the pianola roll edition may be part of the solution. Furthermore, the solution (if it exists) "must be multivalent, must deal with musical as well as cryptographic issues, must produce workable counterpoint within Elgar's stylistic range, and must at the same time seem obvious (and not just to its begetter)".[31]

Elgar accepted none of the solutions proposed in his lifetime, and took the secret with him to the grave.

The prospect of gaining new insights into Elgar's character and composition methods, and perhaps revealing new music, continues to motivate the search for a definitive solution. But Norman Del Mar expressed the view that "there would be considerable loss if the solution were to be found, much of the work's attraction lying in the impenetrability of the riddle itself", and that interest in the work would not be as strong had the Enigma been solved during Elgar's lifetime.[32]

Counterpoints

[edit]Solutions in this category suggest a well-known tune which (in the proponent's view) forms a counterpoint to the theme of the Variations.

- After Elgar's death in 1934 Richard Powell (husband of Dorabella) published a solution proposing Auld Lang Syne as the countermelody.[33] This theory has been elaborated by Roger Fiske,[34] Eric Sams[35] and Derek Hudson.[36] Elgar himself, however, is on record as stating "Auld Lang Syne won't do".[37] Ernest Tomlinson revived the idea in 1976, providing his "proof" in the form of his set of variations Fantasia on Auld Lang Syne.[38]

- Reviewing published Enigma solutions in 1939, Ernest Newman failed to identify any that met what he considered to be the required musical standard.[39]

- A competition organized by the American magazine The Saturday Review in 1953 yielded one proposed counterpoint – the aria Una bella serenata from Mozart's Così fan tutte (transposed to the minor key).[40]

- In 1993 Brian Trowell, surmising that Elgar conceived the theme in E minor, proposed a simple counterpoint consisting of repeated semibreve E's doubled at the octave – a device occasionally used by Elgar as a signature.[41]

- In 1999 Julian Rushton[42] reviewed solutions based on counterpoints with melodies including Home, Sweet Home, Loch Lomond, a theme from Brahms's fourth symphony, the Meditation from Elgar's oratorio The Light of Life[43] and God Save the Queen – the last being Troyte Griffith's suggestion from 1924, which Elgar had dismissed with the words "Of course not, but it is so well-known that it is extraordinary no-one has found it".[39]

- In 2009, composer Robert Padgett[44] proposed Martin Luther's "Ein feste Burg" as a solution, which was later described as "[lying] at the bottom of a rabbit hole of anagrams, cryptography, the poet Longfellow, the composer Mendelssohn, the Shroud of Turin, and Jesus, all of which he believes he found hiding in plain sight in the music."[45]

- In 2021, architectural acoustician Zackery Belanger proposed Elgar's own "Like to the Damask Rose" as a solution, claiming that the fourteen deaths described in the song align with the fourteen variations. Belanger arrived at this conclusion in his attempt to solve Elgar's Dorabella Cipher, which he proposes has a rose-shaped key assembled from the cipher's symbols.[46]

A few more solutions of this type have been published in recent years. In the following three examples the counterpoints involve complete renditions of both the Enigma theme and the proposed "larger theme", and the associated texts have obvious "dark" connotations.

- In his book on the Variations Patrick Turner advanced a solution based on a counterpoint with a minor key version the nursery rhyme Twinkle, twinkle, little star.[47]

- Clive McClelland has proposed a counterpoint with Sabine Baring-Gould's tune for the hymn Now the Day Is Over (also transposed to the minor).[48]

- Tallis's canon, the tune for the hymn Glory to Thee, my God, this night, features as a cantus firmus in a solution which interprets the Enigma as a puzzle canon. This reading is suggested by the words "for fuga", which appear among Elgar's annotations to his sketch of the theme.[49]

Another theory has been published in 2007 by Hans Westgeest.[50] He has argued that the real theme of the work consists of only nine notes: G–E♭–A♭–F–B♭–F–F–A♭–G.[51][52] The rhythm of this theme (in 4

4 time, with a crotchet rest on the first beat of each bar) is based on the rhythm of Edward Elgar's own name ("Edward Elgar": short-short-long-long, then reversed long-long-short-short and a final note). Elgar meaningfully composed this short "Elgar theme" as a countermelody to the beginning of the hidden "principal Theme" of the piece, i.e. the theme of the slow movement of Beethoven's Pathétique sonata, a melody which indeed is "larger" and "well-known".

When the two themes are combined each note of (the first part of) the Beethoven theme is followed by the same note in the Elgar theme. So musically Elgar "follows" Beethoven closely, as Jaeger told him to do (see above, Var. IX) and, by doing so, in the vigorous, optimistic Finale the artist triumphs over his sadness and loneliness, expressed in the minor melody from the beginning. The whole piece is based on this "Elgar theme", in which the Beethoven theme is hidden (and so the latter "goes through and over the whole set, but is not played"). Dora Penny could not solve the enigma. Elgar had expected she would: "I'm surprised. I thought that you of all people would guess it." Even later she could not when Elgar had told her in private about the Beethoven story and the Pathétique theme behind the Jaeger/Nimrod-variation (see above, Var. IX) because she did not see the connection between this and the enigma.

Other musical themes

[edit]If Robert John Buckley's statement about the theme being "a counterpoint to some well-known melody" (which is endorsed by what Elgar himself disclosed to F. G. Edwards in 1900) is disregarded or discounted the field opens up to admit other kinds of connection with well-known themes.

- Entries in this category submitted to the Saturday Review competition included the suggestions: When I am laid in earth from Purcell's Dido and Aeneas, the Agnus Dei from Bach's Mass in B minor, the song None shall part us from Iolanthe and the theme from the slow movement of Beethoven's Pathétique sonata.[53] Elgar himself affirmed that this Beethoven theme is alluded to in variation IX.[54]

- In 1985 Marshall Portnoy suggested that the key to the Enigma is Bach's The Art of Fugue.[55] Contrapunctus XIV of that work contains the BACH motif (in English notation, B♭–A–C–B♮) which, in Portnoy's view, can also be found in the Variations. Moreover, the Art of Fugue consists of 14 individual fugues on the same subject (just as the Enigma variations are 14 variations on the same subject), and Bach signed his name "B-A-C-H" within the 14th fugue (just as Elgar signed his name "EDU" on the 14th variation), as well as other clues.

- Theodore van Houten proposed in 1975 Rule, Britannia! as the hidden melody on the strength of a resemblance between one of its phrases and the opening of the Enigma theme. The word which is sung to this phrase – a thrice-repeated "never" – appears twice in Elgar's programme note, and the figure of Britannia on the penny coin provides a link with Dora Penny.[56] The credibility of the hypothesis has received a boost from a report that it was endorsed by Elgar himself.[57]

- Ed Newton-Rex superimposed the enigma theme on Pergolesi's Stabat Mater, showing a clear contrapuntal relationship. He claims that the theme being written on top of existing music is the logical way of theme being created, so that is the approach to be used in solving the enigma. It is also worth noting the double barline which encloses the area based on the Stabat Mater.[58]

- Other tunes which have been suggested on the basis of a postulated melodic or harmonic connection to Elgar's theme include Chopin's Nocturne in G minor,[59] John Dunstable's Ave Maris Stella,[60] the Benedictus from Stanford's Requiem,[61] Pop Goes the Weasel,[62] Brahms's "Four Serious Songs",[63] William Boyce's Heart of Oak (transposed to the minor),[64] the Dies irae plainchant[65] and Gounod's March to Calvary.[66]

Non-musical themes

[edit]- Ian Parrott wrote in his book on Elgar[67] that the "dark saying", and possibly the whole of the Enigma, had a biblical source, 1 Corinthians 13:12, which in the Authorised Version reads, "For now we see through a glass, darkly (enigmate in the Latin of the Vulgate); but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known." The verse is from St. Paul's essay on love. Elgar was a practising Roman Catholic and on 12 February 1899, eight days before the completion of the Variations, he attended a Mass at which this verse was read.[68]

- Edmund Green suggested that the "larger theme" is Shakespeare's sixty-sixth sonnet and that the word "Enigma" stands for the real name of the Dark Lady of the Sonnets.[69]

- Andrew Moodie, casting doubt on the idea of a hidden melody, postulated that Elgar constructed the Enigma theme using a cipher based on the name of his daughter, Carice.[70]

- In 2010 Charles and Matthew Santa argued that the enigma was based on pi, following the misguided attempt by the Indiana House of Representatives to legislate the value of pi in 1897. Elgar created an original melody containing three references to Pi based on this humorous incident. The first four notes are scale degree 3–1–4–2, decimal pi, and fractional pi is hidden in the "two drops of a seventh" following the first 11 notes leading to 2⁄7 × 11 = 22⁄7, fractional pi. His "dark saying" is a pun set off by an unexplained double bar after the first 24 notes (all black notes)..."Four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie (pi)". Shortly before his death, Elgar wrote three sentences about the variations and each sentence contains a hint at pi.[71]

- Some writers have argued that the "larger theme" is friendship, or an aspect of Elgar's personality, or that the Enigma is a private joke with little or no substance.[39][72][73][74]

- Inspector Mark Pitt has recently suggested (as reported by the Sunday Telegraph) that the larger theme is 'Prudentia' which in turn is related to the initials from the variation titles which then forms the Principal 'Enigma' Variations theme.[75]

Subsequent history

[edit]Elgar himself quoted many of his own works, including "Nimrod" (Variation IX), in his choral piece of 1912, The Music Makers. On 24 May 1912 Elgar conducted a performance of the Variations at a Memorial Concert in aid of the family survivors of musicians who had been lost in the Titanic disaster.[76]

There is some speculation that the Enigma machine employed extensively by Nazi Germany during World War II was named after Elgar's Enigma Variations.[77][dubious – discuss]

Frederick Ashton's ballet Enigma Variations (My Friends Pictured Within) is choreographed to Elgar's score with the exception of the finale, which uses Elgar's original shorter ending (see above), transcribed from the manuscript by John Lanchbery. The ballet, which depicts the friends and Elgar as he awaits Richter's decision about conducting the premiere, received its first performance on 25 October 1968 at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London.[78]

The acclaimed 1974 television play Penda's Fen includes a scene where the young protagonist has a vision of an aged Elgar who whispers to him the "solution" to the Enigma, occasioning astonishment on the face of the recipient. A solution to the Enigma also features in Peter Sutton's 2007 play Elgar and Alice.

Elgar suggested that in case the Variations were to be a ballet the Enigma would have to be represented by "a veiled dancer". Elgar's remark suggested that the Enigma in fact pictured "a friend", just like the variations. His use of the word "veiled" possibly indicates that it was a female character.

The Enigma Variations inspired a drama in the form of a dialogue – original title Variations Énigmatiques (1996) – by the French dramatist Éric-Emmanuel Schmitt.

The 2017 film Dunkirk features adapted versions of Elgar's Variation IX (Nimrod), the primary adaptation given the name "Variation 15" on the soundtrack in honor of its inspiration.

Recordings

[edit]There have been more than sixty recordings of the Variations since Elgar's first recording, made by the acoustic process in 1924. Elgar himself conducted the Royal Albert Hall Orchestra for its first electrical recording in 1926 on the HMV label. That recording has been remastered for compact disc; the EMI CD couples it with Elgar's Violin Concerto conducted by the composer with Yehudi Menuhin as the soloist. Sixty years later, Menuhin took the baton to conduct the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in the Variations for Philips, as a coupling to the Cello Concerto with Julian Lloyd Webber. Other conductors who have recorded the work include Arturo Toscanini, Sir John Barbirolli, Daniel Barenboim, Sir Georg Solti, Leonard Bernstein, Giuseppe Sinopoli, Leopold Stokowski, Eugene Ormandy, Pierre Monteux, William Steinberg and André Previn, as well as leading English conductors from Sir Henry Wood and Sir Adrian Boult to Sir Simon Rattle.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Also published as Variations for Orchestra, Variations on an Original Theme, etc.

- ^ a b Elgar's programme note for a performance of the Variations in Turin, October 1911

- ^ Elgar's original text names Lady Mary Lygon. She sailed for Australia after the completion of the Variations but before the work's first performance.

References

[edit]- ^ Moore 1984, pp. 247–252.

- ^ Moore 1984, p. 252.

- ^ a b Moore 1984, pp. 273, 289

- ^ Moore 1984, p. 350.

- ^ Kennedy 1987, p. 179.

- ^ McVeagh 2007, p. 146.

- ^ For example see Powell 1947, p. 39

- ^ As she wrote later in her book (Powell 1947, pp. 110–111).

- ^ "Greek tragedy: Orchestra plays emotional farewell as state broadcaster closes". ITV News. 17 June 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ^ Lane, Anthony (24 July 2017). "Christopher Nolan's Wartime Epic". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 24 July 2017. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ Burr, Ty (20 July 2017). "Dunkirk is a towering achievement, made with craft, sinew, and honesty". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 24 July 2017. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ Quotation from the booklet by Elgar 1946

- ^ Kennedy 1987, p. 96.

- ^ Moore, Jerrold Northrop (November 1999). "The Return of the Dove to the Ark – "Enigma" Variations a Century on" (PDF). Elgar Society Journal. 11 (3). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Burley & Carruthers 1972, pp. 125–127.

- ^ Atkins 1984, pp. 477–480.

- ^ Kennedy 1987, pp. 96–97, 330.

- ^ Blamires, Ernest (July 2005). "'Loveliest, Brightest, Best': a reappraisal of 'Enigma's' Variation XIII (Part I)" (PDF). Elgar Society Journal. 14 (2): 19–34. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Blamires, Ernest (November 2005). "'Loveliest, Brightest, Best': a reappraisal of 'Enigma's' Variation XIII (Part II)" (PDF). Elgar Society Journal. 14 (3): 25–38. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Elgar 1946, Var. XIV.

- ^ Ernest Parkin, "Elgar and Literature", The Elgar Society Journal, November 2004

- ^ "Edward Elgar – Enigma Variations, chamber edition, georgeconducts.co.uk

- ^ Young 1965, p. 54.

- ^ Turner 2007, p. 46.

- ^ Edwards 1900.

- ^ In the introduction to his book, Buckley claims that he stayed as close as possible to the truth and to the actual words of the composer (Buckley 1905, p. ix).

- ^ Buckley 1905, pp. 54–55.

- ^ a b Powell 1947, pp. 119–120

- ^ Turner 2007, p. 50.

- ^ Atkins 1984, p. 428.

- ^ Rushton 1999, p. 77.

- ^ Del Mar, Norman (1998). Conducting Elgar. Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-816557-9.

- ^ Powell, Richard C., "Elgar's Enigma", Music & Letters, vol. 15 (July 1934), p. 203; quoted in Portnoy 1985.

- ^ Fiske, Roger, "The Enigma: A Solution", The Musical Times, vol. 110 (November 1969), 1124, quoted in Portnoy 1985.

- ^ Sams, Eric, "Variations on an Original Theme (Enigma)", The Musical Times, vol. 111 (March 1970); quoted in Portnoy 1985.

- ^ Hudson, Derek (1984). "Elgar's Enigma: the Trail of the Evidence". The Musical Times. 125 (1701): 636–9. doi:10.2307/962081. JSTOR 962081.

- ^ Westrup, J. A., "Elgar's Enigma", Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association, 86th Sess. (1959–1960), pp. 79–97, Taylor & Francis for the Royal Musical Association, accessed 2 December 2010 (subscription required)

- ^ Grant, M.J (2021). Auld Lang Syne: A Song and its Culture, end of Section 7.3

- ^ a b c

- Newman, Ernest (16 April 1939). "Elgar and his Variations: What was the "Enigma"?". The World of Music. The Sunday Times. No. 6,053. London. p. 5.

- Newman, Ernest (23 April 1939). "Elgar and his Enigma—II: An Innocent Mystification". The World of Music. The Sunday Times. No. 6,054. London. p. 5.

- Newman, Ernest (30 April 1939). "Elgar and his Enigma—III: Some Snags". The World of Music. The Sunday Times. No. 6,055. London. p. 5.

- Newman, Ernest (7 May 1939). "Elgar and his Enigma—IV". The World of Music. The Sunday Times. No. 6,056. London. p. 7.

- ^ "What is the Enigma?". Saturday Review. 30 May 1953.

- ^ Trowell, B. Edward Elgar: Music and Literature in Monk 1993, p. 307

- ^ Rushton 1999, pp. 71–73.

- ^ Rollet, J. M. (November 1997). "New Light on Elgar's Enigma". Elgar Society Journal. 10 (3).

- ^ Padgett, Robert (10 April 2016). "Evidence for "Ein feste Burg" as the Covert Theme to Elgar's Enigma Variations".

- ^ Estrin, Daniel (1 February 2017). "Breaking Elgar's Enigma". New Republic.

- ^ Belanger, Zackery (3 September 2024). "An Enigma, a Cipher, and a Rose" (PDF). Dear Cipher. Retrieved 3 September 2024.

- ^ Turner 2007, pp. 111–116 (reviewed in The Elgar Society Journal, March 1999).

- ^ McClelland, Clive (2007). "Shadows of the evening: new light on Elgar's "dark saying"". The Musical Times. 148 (1901): 43–48. doi:10.2307/25434495. JSTOR 25434495.

- ^ Gough, Martin (April 2013). "Variations on a Canonical Theme – Elgar and the Enigmatic Tradition". Elgar Society Journal. 18 (1).

- ^ "The most plausible theory so far is by Hans Westgeest. He demonstrates that the theme has the same contours as the melody from the second movement of Beethoven's Sonata Pathétique. The link can indeed be demonstrated and the connection with the anecdote of Augustus Jaeger gives the link credibility." (transl.) Prof. Dr. Francis Maes (University Ghent). Program note Concertgebouw Brugge (BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, cond. Martyn Brabbins, 3 June 2018).

- ^ See Westgeest 2007. The book has been reviewed in the Elgar Society Journal, vol. 15, no. 5 (July 2008), pp. 37–39, and no. 6 (November 2008), p. 64.

- ^ "Hans Westgeest – Biografie". Hanswestgeest.nl. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ "What is the Enigma?", Saturday Review, 30 May 1953. The arguments which J. F. Wohlwill gave to sustain his Pathétique-solution are very vague and seem to be inspired just by what Elgar had written in the programme notes for the pianola rolls (1929); see Westgeest 2007, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Powell 1947, p. 111.

- ^ Portnoy, Marshall A. (1985). "The Answer to Elgar's 'Enigma'". The Musical Quarterly. 71 (2). Oxford University Press: 205–210. doi:10.1093/mq/LXXI.2.205. JSTOR 948136. (subscription required)

- ^ Hierck, Hans (30 December 1975). "Geheim van Edward Elgar ontraadseld". de Volkskrant. p. 9.

Reichenfeld, J. (16 January 1976). "The Theme Never Appears". Cultureel Supplement JRC Handelsblad.

"The Enigma – A Solution from Holland". Elgar Society Newsletter: 28–32. January 1976.

van Houten, Theo (1976). "Het Enigma van Edward Elgar". Mens&Melodie 31: 68–78.

van Houten, Theodore (May 1976). ""You of all people": Elgar's Enigma". The Music Review. 37 (2): 132–142.

""Correspondence"". The Music Review: 317–319. November 1976.

van Houten, Theodore (2008). "The enigma I will not explain". Mens & Melodie. 63 (4): 14–17. - ^ Walters, Frank; Walters, Christine (March 2010). "Some Memories of Elgar: and a note on the Variations". Elgar Society Journal. 16 (4): 23–27.

- ^ Roberts, Maddy Shaw: Young composer "solves" Elgar's Enigma – and it's pretty convincing. Classic FM, 1 May 2019

- ^ Eric Blom's suggestion. See Reed 1939, p. 52: "For a few bars it fits in counterpoint with Chopin's G minor Nocturne, Op. 37, No. 1. – E. B."

- ^ Laversuch, Robert (1976). Elgar Society Newsletter: 22.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Berlins, Marcel (20 August 1977). "Enigma of Elgar's debt to a fellow composer: Comparisons show that much-admired theme may not be original". The Times. No. 60,087. London. pp. 1–2.

- ^ "Pop Goes the Enigma", letter in Music and Musicians, XXVI (1977), pp. 4–5.

- ^ Skouenberg, Ulrik (1984). Music Review. 43: 161–168.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Ross, Charles (September 1994). "A Key to the Enigma". Elgar Society Journal. 8 (6).

- ^ Kingdon, Ben (May 1979). "The 'Enigma' – A Hidden 'Dark Saying'". Elgar Society Journal. 1 (2).

- ^ Edgecombe, Rodney (November 1997). "A Source for Elgar's Enigma". Elgar Society Journal. 10 (3).

- ^ Parrott 1971, pp. 46–49.

- ^ Alice Elgar's diary, 12 February 1899: "E. to St. Joseph's"

- ^ Green, Edmund (November 2004). "Elgar's "Enigma": a Shakespearian solution". Elgar Society Journal. 13 (6): 35–40.

- ^ Moodie, Andrew (November 2004). "Elgar's 'Enigma': the solution?". Elgar Society Journal. 13 (6): 31–34.

- ^ Santa, Charles Richard; Santa, Matthew (Spring 2010). "Solving Elgar's Enigma". Current Musicology (89).

- ^ Moore, Jerrold Northrop (February 1959). Music Review: 38–44.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)[incomplete short citation] - ^ Kennedy 1987, p. 85.

- ^ Ling, John (July 2008). "The Prehistory of Elgar's Enigma". Elgar Society Journal. 15 (5): 8–10.

- ^ Bird, Steve (12 January 2019). "Police inspector claims he has solved the mystery behind Elgar's Enigma Variations". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- ^ Moore 1984, p. 634.

- ^ "Has a Cleveland policeman cracked the secret of Elgar's Enigma Variations?". The Guardian. 3 May 2017. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Lanchbery J. Enigma Variations, in Royal Opera House programme, 1984.

Bibliography

[edit]- Atkins, Wulstan (1984). The Elgar-Atkins Friendship. Newton Abbot: David & Charles.

- Buckley, Robert John (1905). Sir Edward Elgar. London / New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Burley, Rosa; Carruthers, Frank C. (1972). Edward Elgar: The Record of a Friendship. London: Barrie and Jenkins. ISBN 9780214654107.

- Edwards, F. G. (1900). "Edward Elgar". The Musical Times. 41. Reprinted in: Redwood 1982, pp. 35–49.

- Elgar, Edward (1946). My Friends Pictured Within. The subjects of the Enigma Variations as portrayed in contemporary photographs and Elgar's manuscript. London: Novello.

- Kennedy, Michael (1987). Portrait of Elgar (Third ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-284017-7.

- McVeagh, Diana (2007). Elgar the Music Maker. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-295-9.

- Monk, Raymond, ed. (1993). Edward Elgar – Music and Literature. Aldershot: Scolar Press.

- Moore, Jerrold Northrop (1984). Edward Elgar: A Creative Life. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-315447-1.

- Parrott, Ian (1971). Master Musicians – Elgar. London: J. M. Dent & Sons.

- Powell, Mrs. Richard (1947). Edward Elgar: Memories of a Variation (2nd ed.). London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Redwood, Christopher, ed. (1982). An Elgar Companion. Ashbourne.

- Reed, W. H. (1939). Elgar. London: J. M. Dent and Sons.

- Rushton, Julian (1999). Elgar: 'Enigma' Variations. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-63637-7.

- Turner, Patrick (2007). Elgar's 'Enigma' Variations – A Centenary Celebration (second ed.). London: Thames Publishing.

- Westgeest, Hans (2007). Elgar's Enigma Variations. The Solution. Leidschendam-Voorburg: Corbulo Press. ISBN 978-90-79291-01-4. (hardcover), ISBN 978-90-79291-03-8 (paperback)

- Young, Percy M., ed. (1965). Letters to Nimrod. London: Dobson Books.

Further reading

[edit]- Adams, Byron (Spring 2000). "The 'Dark Saying' of the Enigma: Homoeroticism and the Elgarian Paradox". 19th-Century Music. 23 (3): 218–235. doi:10.2307/746879. JSTOR 746879.

- Nice, David (1996). Edward Elgar: An Essential Guide to His Life and Works. London: Pavilion. ISBN 1-85793-977-8.

External links

[edit]- Enigma Variations CDs

- Piano adaptation of Enigma Variations in MIDI file (104KB) The theme and its 14 variations are located at ca. [00:00, 00:55, 02:05, 02:55, 04:20, 04:50, 06:25, 07:30, 08:28, 09:50, 12:22, 14:55, 15:53, 17:38, 19:13] in this 24-min track.

- Enigma Variations: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Julia Trevelyan Oman Archive University of Bristol Theatre Collection, University of Bristol

- John Pickard, "Variations on an Original Theme (Enigma) (1898–9)" from BBC Radio 3

- Discovering Music Enigma Variations

- The Enigma I Will Not Explain on BBC Radio 4

- Video on YouTube, Leonard Slatkin introduced Elgar's Enigma Variations, from BBC Proms 1995 (includes original ending)

- Elgar Society Journal archive

- Enigma variations, Op. 36 on Musopen

Variation IX

[edit]- Complete variation on YouTube, performed by the Berlin Philharmonic conducted by Simon Rattle in 2012