Poro (opera)

| Poro | |

|---|---|

| Opera seria by George Frideric Handel | |

Title page of score, 1731 | |

| Language | Italian |

| Based on | Metastasio's Alessandro nell'Indie |

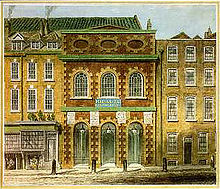

| Premiere | 2 February 1731 King's Theatre, Haymarket, London |

Poro, re dell'Indie ("Porus, King of the Indians", HWV 28) is an opera seria in three acts by George Frideric Handel. The Italian-language libretto was adapted from Alessandro nell'Indie by Metastasio, and based on Alexander the Great's encounter with Porus in 326 BC. The libretto had already been set to music by Leonardo Vinci in 1729 and was used as the text for more than sixty operas throughout the 18th century.[1]

Graham Cummings has examined in detail the composition history of Poro in the context of Handel's work on his London operas during the 1730s, and has postulated the principal time of Handel's composing from September 1730 to 16 January 1731, with small revisions prior to the 2 February premiere.[2]

The opera shifted the story's emphasis from Alessandro to Poro and Cleofide, and their relationship.

Performance history[edit]

The opera was first given at the King's Theatre in London on 2 February 1731 and on 15 further occasions. A run of 16 performances was a mark of success for the time as is the fact that the work was revived on 23 December 1731, and again in a revised form on 8 December 1736. It was also given in Germany in Hamburg and Braunschweig.

The first modern performance, also in Braunschweig, was in 1928. The first UK performance since Handel's time was in 1966 at Abingdon.[3] As with all Baroque opere serie, Poro went unperformed for many years, but with the revival of interest in Baroque music and historically informed musical performance since the 1960s, Poro, like all Handel operas, receives performances at festivals and opera houses today.[4] Among other performances, Poro was staged at the Göttingen International Handel Festival in 2006,[1] by the London Handel Festival in 2007[5] and in a German-language production directed by Harry Kupfer and conducted by Jörg Halubek at the Komische Oper Berlin in 2019.[6]

Roles[edit]

| Role[7] | Voice type | Premiere cast, 2 February 1731[8] |

|---|---|---|

| Poro, Indian King | alto castrato | Francesco Bernardi, called "Senesino" |

| Cleofide, Poro's wife | soprano | Anna Maria Strada del Pò |

| Erissena, Poro's sister | contralto | Antonia Merighi |

| Gandarte, Erissena's lover | contralto | Francesca Bertolli |

| Alessandro, King of Macedonia | tenor | Annibale Pio Fabri 'Balino' |

| Timagene, Alexander's general | bass | Giovanni Giuseppe Commano |

Synopsis[edit]

- Scene: By the Hydapses River, about 327 B.C.

Act 1[edit]

Alessandro has conquered India and its King, Poro, who in despair wants to take his own life, but is restrained by his friend Gandarte who reminds the King of his loving wife Queen Cleofide and how distraught she would be at his death. To prevent the King's capture by the advancing troops, he and Gandarte switch clothes so that Gandarte now appears to be the King and the King a simple warrior, "Asbite". Poro in this disguise is captured however and taken to Alessandro.

Poro's sister Erissena is also taken to Alessandro and captivates both the commander and his general, Timagene.

Poro in disguise makes his way into the palace where he is reunited with his wife Cleofide. He is distraught however when she sends a friendly greeting to the victorious Alessandro and sets out to pay him a visit, fearing that his wife will betray him with the conqueror. Gandarte brings word to Poro that Alessandro has fallen for their disguise and believes Gandarte to be the King, and that Alessandro's troops are dissatisfied and planning to mutiny.

Gandarte is in love with Erissena and is unhappy to find her full of praise for the many qualities of Alessandro.

Cleofide appeals to Alessandro to show mercy to her defeated husband. Alessandro is charmed by Cleofide's person, which Poro observing in his disguise as "Asbite" feels is evidence that his wife is planning to betray him. Cleofide accuses her husband of suspecting her unjustly.

Act 2[edit]

Alessandro pays a visit to Cleofide in the palace, further inflaming Poro's jealousy, who decides to launch an attack against Alessandro with his army, but he is once again defeated. In despair, he decides that the only way out is death both for himself and his wife and is going to kill first her and them himself but he is discovered by Alessandro just as he is about to stab Cleofide and Alessandro has the supposed "Asbite" arrested.

Timagene releases "Asbite" however. Timagene knows that Alessandro's troops are planning to mutiny and is now on their side. He thinks "Asbite" may be able to help them.

Alessandro proposes to Cleofide that she become his Queen now, but she refuses. Erissena brings terrible news – Poro in trying to escape, has been drowned attempting to cross a river. Cleofide is devastated.

Act 3[edit]

Erissena meets the disguised Poro in the royal gardens, astonished to find him alive. Poro is determined to be revenged on Alessandro and conspires with Timagene to kill him.

Cleofide tells Alessandro she will marry him after all, but really she is planning to immolate herself on a pyre directly after the marriage.

In the temple prepared for the marriage, with a sacrificial fire upon which Cleofide intends to throw herself, she is about to marry Alessandro when Poro appears and sinks to his knees before his wife, begging her to change her mind. For the first time, Alessandro realises that "Asbite" is really Poro and is deeply moved by such marital devotion. Alessandro forgives the conspiracy against him, will allow Poro and Cleofide to live together undisturbed and requests Poro's hand in friendship. All celebrate the fortunate outcome of events.[9]

Context and analysis[edit]

The German-born Handel, after spending some of his early career composing operas and other pieces in Italy, settled in London, where in 1711 he had brought Italian opera for the first time with his opera Rinaldo. A tremendous success, Rinaldo created a craze in London for Italian opera seria, a form focused overwhelmingly on solo arias for the star virtuoso singers. In 1719, Handel was appointed music director of an organisation called the Royal Academy of Music (unconnected with the present-day London conservatoire), a company under royal charter to produce Italian operas in London. Handel was not only to compose operas for the company but hire the star singers, supervise the orchestra and musicians, and adapt operas from Italy for London performance.[10][11]

The Royal Academy of Music collapsed at the end of the 1728–29 season, partly due to the huge fees paid to the star singers. A bitter rivalry had developed between the supporters of the two prima donnas who had appeared in Handel's last few operas, Francesca Cuzzoni and Faustina Bordoni, culminating in June 1727 with a brawl in the audience while the two prima donnas onstage stopped singing, traded insults and pulled each other's hair, to enormous public scandal satirized in the popular The Beggar's Opera of 1728 and bringing Italian opera of the kind Handel composed into a certain amount of ridicule and disrepute.[12][13][14][15] At the end of the 1729 season, both ladies and the star castrato Senesino who had appeared to great acclaim in numerous operas by Handel left London for engagements in continental Europe. Handel went into partnership with John James Heidegger, the theatrical impresario who held the lease on the King's Theatre in the Haymarket where the operas were presented and started a new opera company with a new prima donna, Anna Strada. The cast Handel had assembled for his first opera in the new venture, Lotario, had included a castrato, Antonio Bernacchi, who had not been very popular with London audiences and with Poro Senesino made a triumphant return to the London stage, for even greater fees.[9]

Poro was a success with London audiences, as 18th-century musicologist Charles Burney wrote:

This opera, though it contains but few airs in a great and elaborate style, was so dramatic and pleasing, that it ran fifteen nights successively in the spring season, and was again brought on the stage in the autumn, when it sustained four representations more.[16]

According to Sir Walter Newman Flower:

Poro, with its background of Oriental romance, was instantly a success. Never did Senesino in all his London singing rise to a greater height than with the air "Se possono tanto". He had never been out of favour, now he attained in one night a far greater popularity than ever. In a week all London was humming the airs. Many declared that Poro was the best opera (Handel) had given London.[17]

Musical historian Graham Cummings has said of Poro: "With very few exceptions the arias rank amongst Handel's finest work, widely varied in style and often richly scored."[7]

The opera is scored for two recorders, flute, two oboes, bassoon, trumpet, two horns, strings, and continuo (cello, lute, harpsichord).

Recordings[edit]

Europa Galante conducted by Fabio Biondi with Gloria Banditelli (Poro), Rossana Bertini (Cleofide), Bernada Fink (Erissena), Gérard Lesne,(Gandarto), Sandro Naglia (Alessandro), Timagene (Roberto Abbondanza), recorded 1994. CD: Opus 111 Cat: OP30-113/5[18][19]

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Poro, re dell'Indie". Gfhandel.org. Handel Institute. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ^ Cummings, Graham, "Handel's Compositional Methods in His London Operas of the 1730s, and the Unusual Case of Poro, rè dell'Indie (1731)" (August 1998). Music & Letters, 79 (3): pp. 346–367.

- ^ Dean, Winton, "Reports: Abingdon – Handel's Poro" (November 1966). The Musical Times, 107 (1485): p. 978.

- ^ "Handel: A Biographical Introduction". Handel Institute. Archived from the original on 2 September 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ^ "Poro, re dell'Indie". Operatoday.com. Retrieved 3 July 2004.

- ^ des Aubris, Zenaida. "Handel in the British Raj: Harry Kupfer returns to Komische Oper". Bachtrack. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- ^ a b "List of Handel's works". Gfhandel.org. Handel Institute. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ^ Casaglia, Gherardo (2005). "Poro, 2 February 1731". L'Almanacco di Gherardo Casaglia (in Italian).

- ^ a b Angela, Kuhk. "Handel House – Handel's Operas: Poro". Handel and Hendrix. Handel House Museum. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ^ Dean, Winton; Knapp, J. Merrill (1995). Handel's Operas, 1704–1726. Clarendon Press. p. 298. ISBN 9780198164418.

- ^ Strohm, Reinhard (20 June 1985). Essays on Handel and Italian Opera. CUP Archive. ISBN 978-0-521-26428-0. Retrieved 2 February 2013 – via Google Books.

- ^ Hicks, Anthony. "Programme Notes for The Rival Queens". Hyperion Records. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- ^ Snowman, Daniel (2010). The Gilded Stage: A Social History of Opera. Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-84354-466-1.

- ^ Dean, Winton (1997). The New Grove Handel. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-30358-2.

- ^ "Handel and the Battle of the Divas". Classic FM. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ^ Charles Burney: A General History of Music: ... Vol. 4. London 1789, p. 353.

- ^ Walter Newman Flower: George Frideric Handel; His Personality & His Times. Waverley Book Co., London 1923, reprint: Charles Scribner's Sons, New York 1948, pp. 205f.

- ^ Burrows, Donald, "Recording Reviews: Three Handel Operas" (August 1996). Early Music, 24 (3): pp. 522–524.

- ^ Händel, Georg Friedrich; Abbondanza, Roberto; Banditelli, Gloria; Bertini, Rossana; Biondi, Fabio; Fink, Bernarda; Lesne, Gérard; Naglia, Sandro; Europa Galante (1994), Poro, rè dell'Indie (opera), Paris: Opus Production, OCLC 705244346

Further reading[edit]

- Hicks, Anthony, "Poro", The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, ed. Stanley Sadie (London, 1992) ISBN 0-333-73432-7.

External links[edit]

- Poro, re dell'Indie, HWV 28 (Handel): Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Italian libretto Archived 5 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Score of Poro (ed. Friedrich Chrysander, Leipzig 1880)